Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - July 2022 - Going Loco - July 2022

Going Loco - July 2022

FRIDAY 29 JULY

Brown - Part 3 - The GWR's Monstrous Regiment?*

Our continuing brown vehicle safari continues this time with a look at one of my favourite names for a bit of Great Western Railway rolling stock ever. We took a little look at the smaller end of the Covered Carriage Truck (CCT) family last time in the shape of all PYTHONS great and small. We now need to go big with bogies…

These vehicles are described as CCTs but actually have their origins in a field somewhat removed from the conveyance of road vehicles. It actually comes from the treading the boards, the land of limelight, the magic of theatre. The early 20th century was in some ways the heyday of the travelling theatre company. Indeed, this is where we get the phrase to ‘Get the show on the road’. This is where a show may start in the West End theatre district of London but later on tours the various local theatres in the rest of the country. This was also the same for circuses – large touring shows of all sorts were the norm in the pre-television age.

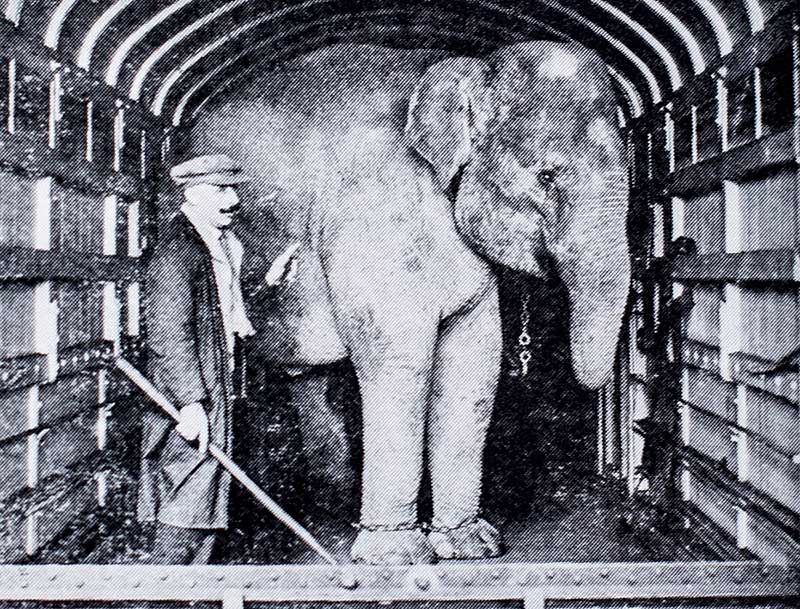

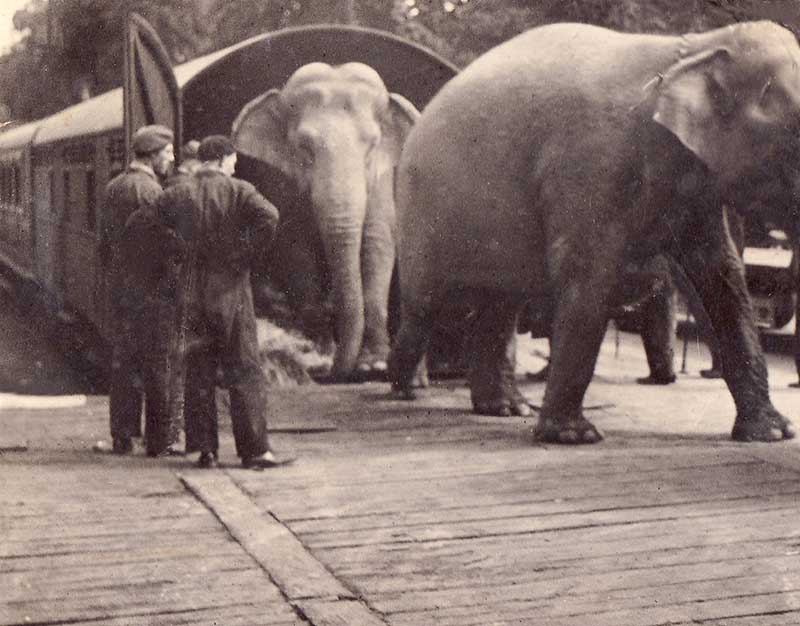

Three elephants (each nine feet tall and weighing two tons) were carried from Fishguard Harbour to Cardiff in a specially strengthened MONSTER on 10 October 1937. This photograph was published in the Great Western Railway Magazine.

The issue with this is that there is an awful lot of very large items that need to travel with these performances. Think about the size of even a moderate stage. The scenery to decorate this has to be quite large in order to fill the inside of the proscenium arch.** There were long open wagons available to the GWR but you really don't want your scenery – which may be made of somewhat absorbent materials such as canvas, wood and the like – getting wet. There was also the option of the full brake coach. These were passenger coaches that had no seats in them and carried luggage, parcels and goods along with a guard's compartment on passenger trains. The issue here is that they have sealed ends. The only way in and out is by doors in the sides. Imagine trying to get something large, long and heavy through a small side facing door. A bit of a non-starter really…

The PYTHONs that we had a look at last week were the way forward. They were essentially covered vehicles that were a ‘tube’ with large loading doors in each end and side doors for platform access. The only issue was that these weren't very long. The GWR needed something new. Churchward's carriage and wagon design team simply took the PYTHON design and stretched it. Quite a bit – the body of the vehicle now measured some 50’ and it weighed over 25 tons empty. This was too big for a 4 wheel vehicle, so two four wheel bogies to what is known as the 9’ wheelbase ‘American’ design were added.

Outside framed MONSTER photographed by Jim Russell at Henley-on-Thames in 1947

The first three diagram P.16 vehicles were built in Lot 1191 in 1911. They were given the telegraphic code name of MONSTER. These first three MONSTERs (Nos. 490, 491 & 492) were unusual in that they had what is known as outside frames. This means that the framework that makes up the body of the vehicle is exposed and the inside of the frame receives the planking that makes the sides. There were two double doors per side and these were flanked with a window on each side of the pair of doors. They were gas lit although this must only have been used when stationary as there were no corridor connections for any passenger to get to the rest of the train! Like the experimental PYTHON last time, these three vehicles were provided initially with both vacuum and Westinghouse air brakes to ensure operation across the UK rail network.

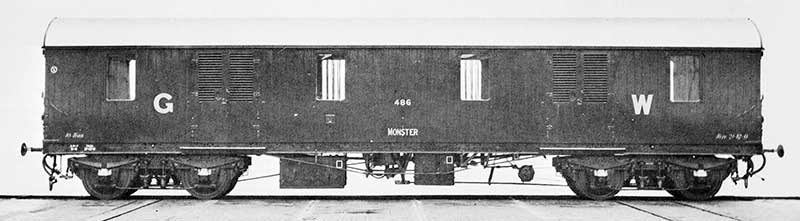

An official photograph of MONSTER No 486, as published in Jim Russell’s book on Great Western Coaches 1903-1948

Like the rest of the majority of brown vehicles, MONSTERs were only built in small batches as and when required. The biggest change to the initial design was to provide a flush sided look with the planking on the outside. The basic layout was a winner though and so the design continued pretty much as is but with the lack of the Westinghouse brake and some examples sporting bogies of varying types. The one at Didcot is privately owned and is currently unrestored, living in the depths of the carriage and wagon store. It was built in 1913 as part of lot 1223 to diagram P18. No 485 was secured for preservation in 1980 from BSC at Port Talbot. This vehicle was in great condition until it was badly damaged in a collision. As a result of this, No 485 was scrapped and No 484 (the only other option) eventually got to Didcot in 1986.

The interior of No 486

There are two other MONSTERs in preservation and they have both been restored. No 594 is with our fellow preservationists at the South Devon Railway where it is used as a semi mobile display space at Totnes. Holding up the British Rail end of things is No W600W. This was built to diagram P24 in 1954. This one lives with the fine people at the Gloucestershire and Warwickshire Railway. The biggest difference with the BR versions was that they were electrically lit from the outset and had the pressed steel style bogies.

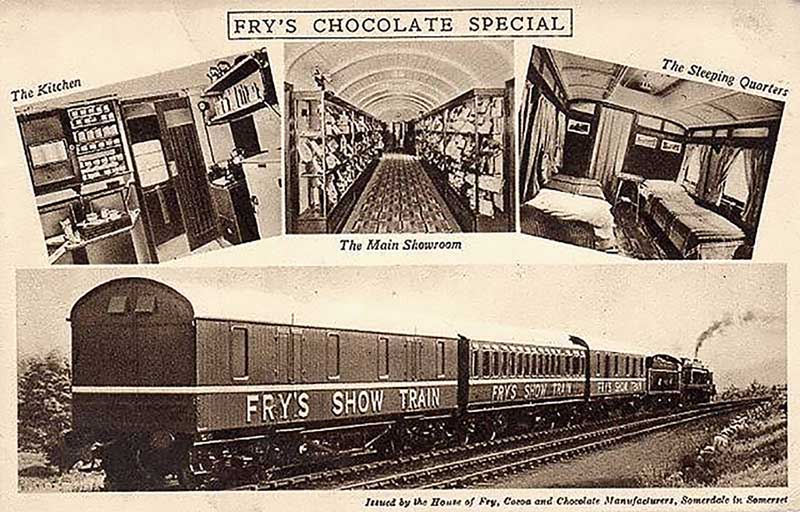

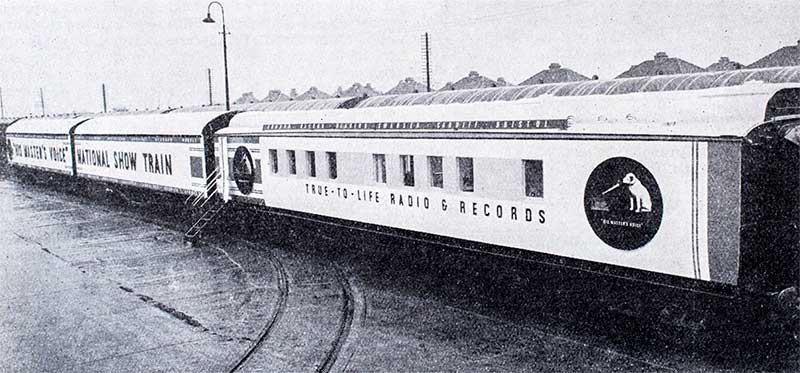

The Fry's chocolate train of 1933 consisting of two MONSTERs with a clerestory restaurant car between them. Photo reproduced by permission of Bristol Culture, ref P9466

There was a variant of the MONSTER known as the GIANT. This was a MONSTER with corridor connections at one end instead of the end doors. This was first done in 1933, as a result of the Fry's chocolate company wanting to use these vehicles as a travelling exhibition on the railway network. Fry's were a good freight customer to the GWR so it is no surprise that this was carried out. Diagram P18 vehicles Nos 590 and 593 were the pair involved and were used in this configuration a second time for another similar exhibition by the His Master's Voice (HMV) company in 1934. After this, they were converted back to MONSTERs again. A second set were converted (Diagram P18 Nos 587 & 591) prior to nationalisation for another travelling exhibition. They were duly converted back afterwards too.

A composite postcard of the Fry's chocolate train. Showcases were installed inside the MONSTERs. The restaurant car also had a bedroom for the staff who travelled with the train

Given their utility, these vehicles were still in service into the mid 1970s. Given that the design dated back to pre WWI, the designs of the GWR once again prove to be both enduring and highly cost effective. Well, that's enough brown vehicles for now. I guess we ought to make sure we get on with something else. After all, the show must go on.***

The HMV show train of 1934 with the two MONSTERs behind the restaurant car

It's just as well that I've got this far in a stage-themed Going Loco without saying Macbeth.

Oh no…

*One for my fellow Terry Pratchett fans…

**The bit of curtain that stays up in order to frame the stage.

***Queen fans too!

FRIDAY 22 JULY

Brown - Part 2 - A Nest of Vipers?

I made the brown vehicle blog title a bit more exciting this time hopefully! So last week we defined what a brown vehicle was. Turns out we aren't sure. We defined what livery they carried. Turns out it wasn't always brown. We tried to define whether they were carriages or coaches and the answer was ‘yes’. So, standing on metaphorical shifting sands with feet of metaphorical clay, we continue…

Python No, 565 at Didcot Railway Centre

The interesting vehicles I want to introduce you to today live under the rather broad umbrella term of Covered Carriage Trucks or CCTs. These are covered wagons that were originally designated as such because they had end doors that allowed the loading and unloading of vehicles and other long loads that could not be easily loaded through side access doors that were usual on most steam age freight rolling stock. The GWR eventually developed a separate set of wagons for moving road vehicles known as the MOGOs, DAMOs and ASMOs* all grouped together in the wagon index under the ‘G’ classification. These were not considered brown vehicles so were XP rated and vacuum brake fitted and as such had the standard freight grey paint scheme.

Our ‘brown’ CCTs, however, took their classifications from the carriage index and they both live in the ‘P’ classification. We will deal with the long bogie version of this type - MONSTER No 484 another time. The 4-wheeled version of this was known as the PYTHON. They had an 18’ wheelbase which is quite long for a 4-wheeled vehicle but not the biggest the GWR had.** To give them maximum load carrying capacity, they were built to the limit of the loading gauge. As tall and as wide as the structures such as platforms, bridges and tunnels and the like would allow. The earlier designs had smaller windows and can be easily identified in photographs this way. The design was not unique to the GWR. The Taff Vale Railway had some very similar looking vehicles built to similar dimensions. Once absorbed in 1923 and repainted into GWR livery, the casual observer would be hard pushed to distinguish them. It's all in the double windows with the over window ventilators you know…

Apart from the progression of the basic design, there were a number of vehicles that were built or modified with either experimental or specific purpose in mind. In the second batch of the P14 design, the last one built (No 560), was fitted with both the standard GWR vacuum braking system and a Westinghouse air brake system too. There was a PYTHON design built in 1909 which is short. Really short. It looks like the larger PYTHON with the windows removed and made about the same size as the standard box van designs that were common in the steam era. For the record, this was built to diagram P7.

Bertram Mills circus elephants at Exeter St David's in the 1930s

The design which we have represented in the collection is the P19. The only really obvious visual difference between the earlier versions was the taller windows. The order – Lot 1238 – was constructed at Swindon in 1914. The PYTHONS were never built in large numbers and this was a batch of 20 vehicles originally. Until one more vehicle was added to the list. This was another of these special wagons – No 580 was built with a specially strengthened floor. The reason? Elephants. Yep, Elephants. In those days, circuses were big business and always travelled with a menagerie of animals. Sometimes these circuses travelled by train. Circuses had elephants, ergo elephants needed to travel by train. This wagon was always different to the others and was known as the one and only PYTHON A.

PYTHON No 560 was a member of the P19 type and was adapted at the beginning of WWII to become part of the GWR firefighting effort against the incendiary bombs raining down on the UK at the time. It had its side doors modified to be wider and a swing out derrick or crane that could be used to lower the supplied Coventry Climax water pump that was be used for fighting fires. It was painted brown (yep!), with black ends and the words FIRE TRAIN in large post office red letters. For the model makers reading this, it was paired with coach No 7995 which was used for accommodation for the fire fighters and more of their equipment that wasn't stored in the PYTHON. That should make an intriguing subject for a model…

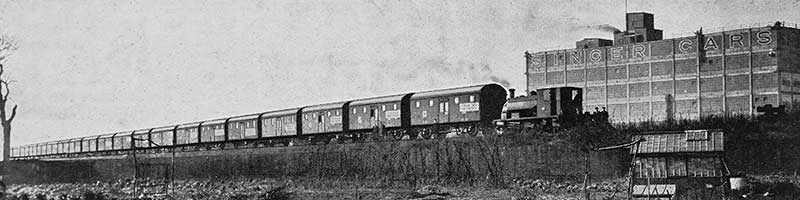

This photograph of a train of Pythons was published in the Great Western Railway Magazine, June 1933 edition. The train was loaded with Singer cars to be taken from the Birmingham factory to the Victoria and Albert and Poplar docks in London for export

The last 6 PYTHONS built at the end of the GWR’s existence were ordered in Lot 1650 and were built to diagram P22. They were numbered 1 to 6. These PYTHON Bs were 32’ long and the wheelbase was now 20’. For the nerdy among us (like me!), they are easily spotted with their flush windows and extra bracing on the sole bars. I told you it was nerdy…

Our PYTHON is No 565, another of the P19 variety and is now the last reminder of the type. Unlike all its brethren, it survived by being converted into a mess and sleeper vehicle for permanent way (track) workers. A job it was happily still doing until 1976. Seeing as it was built in 1914, this represents excellent value for money. Even better value for money when you realise that it is STILL doing that job for society members in 2022! While it’s not restored, it is well loved and is part of the culture of the society. It’s links to the ‘Heavy Freight Mob’ that restored 2-8-0 No 3822 and are well on the way with 2-8-2T No 7202 have meant that a great deal of very happy memories have centred around this vehicle. It was painted black for at least some of its time with us at Didcot and this lead the ‘Mob’ to name their fondly remembered real ale pub ‘The Black Python’.

These photographs, published in Great Western Railway Magazine, May 1933 edition, show cars being loaded at Morris Cowley, during darkness. The lighting was provided by the headlights of the cars

So, it’s a brown vehicle that has been brown, crimson lake, brown, maroon, black and brown. Confused? You should be…

*There’s a blog for that! 5th February 2021. Scroll down on the archive link here:

https://didcotrailwaycentre.org.uk/article.php/378/going-loco-index

**The ASMO mentioned in the link above is pretty darn big for a 4 - wheeler!

FRIDAY 15 JULY

Brown - Part 1

Well, I think I've done it. I think I've managed to find the least interesting title for a Going Loco blog yet. However, for the GWR nerd like myself, brown is a very important colour when we talk about the rolling stock of the Great Western. There were passenger coaches that were designed to transport people at express speeds. These were usually painted chocolate (brown!) and cream*. There were all manner of different freight vehicles. These came in a massive variety of different shapes and sizes and these were usually painted a dark grey colour*. There was however a middle ground – a set of vehicles for goods but for passenger speeds. All flashing past the viewer with a streak of brown.

The brown vehicles are actually a little difficult to define. They tended not to be passenger brake vans or full brakes. These were vehicles that were the shape of passenger coaches and apart from a lack of windows and seats, could pass as a passenger coach. These vehicles could often be found in passenger train formations and as such had the livery of the era to blend in. Travelling post office vehicles were also similarly treated. The brown vehicles inhabited this strange ‘no man's land’ they were built to transport a range of different goods. The first ones we have already discussed in Going Loco are the SIPHONs. There's a blog dedicated to them and their role as milk transport already so look that one up if you missed it! No point in retreading old ground.

A broad gauge train at Pangbourne about 1865. The nearest vehicle looks to be a brown-painted passengers' luggage brake van.

The earliest mention of a brown vehicle dates way back into a specification laid down in January 1852 for an ‘iron passengers' luggage brake van’ which is directed to be painted brown in its entirety with yellow text markings as required. We know that the underframes of these types of vehicles were painted black by the 1880s. There was a brief period between 1912 and 1920 when they followed the passenger coaches into a crimson lake hue but this was short lived and by 1922 repaints of brown vehicles into brown were occurring once again. Apart from differences in text layout and ownership indications, it all pretty much stayed that way until nationalisation and the advent of British Railways when many of the survivors ended up going maroon. Let's start an occasional series that will take a look at examples from the collection at Didcot that exemplify these fascinating vehicles.

The first is exactly not what most enthusiasts think of when they imagine a brown vehicle. This is our example of the HYDRA. This family of vehicles were part of a set of wagons that were grouped together under the ‘G’ index. The job of these wagons was to move motor vehicles about on the railway. Together with the HYDRAs, there are such vehicles as the covered ASMOs, DAMOs and MOGOs and the open well wagons such as the LORIOTs and the flat wagons like the SERPENT or CARFITs.

The basic design of our HYDRA is a wagon with a wooden deck that had a short flat section over the first wheel set. The deck then slopes down to get the main flat load bearing section of the wagon as close to the rails as possible. This means that the load can take advantage of as much height as possible before it starts hitting bridges and tunnel roofs! The deck then slopes back up to pass over the second set of wheels. Buffers on both ends and you have what is termed a ‘well wagon’. The thing that differentiated the HYDRAs from many other types of well wagon types was the fact that they were fitted with vacuum brakes so they could run in passenger trains.

A Royal luggage train from Windsor to Paddington on 21 July 1897, with a road vehicle loaded on a carriage truck.

Their original designation was as ‘road vehicle wagons’ or ‘tramcar trucks’. The idea being that one could attach one's road vehicle to the passenger train one was travelling in and have it unloaded for one's personal use upon arrival at one's destination. As I am rather ‘tongue in cheekily’ implying, this was the province of the well to do! The first of this type known as a HYDRA was built under diagram G10 as far back as the 1880s. This was wagon No. 31336. They were not yet of the well type shape and are really uprated flat wagons at this point. The turn of the century saw the diagram G11 in 1899 that began to take on the ‘modern’ well shape.

Hydra No 42193 without the wooden decking, showing construction of the vehicle.

Our HYDRA was built to diagram G22. The HYDRAs were not built in large numbers being quite specialised and this design only totalled ten vehicles constructed between 1913 and 1917. No. 42193 was one of the last, being built at Swindon as part of lot 745 in 1917. It is designated as a HYDRA D. This sets it apart as a 15 foot long vehicle that is capable of taking vehicle loads of up to 15 tons. This somewhat specialised service offered by the HYDRAs fell out favour as the 20th century went on and as a result ours was the second to last ever built. They were eventually rolled into the well wagon fleet and a wide range of well wagons were eventually reclassified as LOWMACs by British Railways after nationalisation.

The LOWMAC series wagons lasted a long time but as we all know, all good things must come to an end and this particular wagon was recognised by the National Collection as being of some importance so they retained it for preservation. As many Great Western things often do, it found its way to Didcot and has since become part of the society's collection. It still enjoys a working life as, although largely unrestored, it earns its keep as a boiler trolley and has assisted us in the locomotive works with many of the restorations to steam of our locomotives. It just goes to show that even the most humble of our tools sometimes have a really fascinating story to tell!

*I can hear the comments already - massive oversimplification or depends upon your time period. Oh well…

FRIDAY 8 JULY

Cosmetic Wagon Restoration

Going Loco this week is in praise of Ann, who keeps up a programme of excellent work on our wagons. She has been painting and lettering the train of vehicles which sit on No 5 Road alongside the engine shed and loco works. This is not a full restoration, but the aim is to improve their appearance for our visitors and the many thousands of passengers who pass our site each week on Great Western Railway and CrossCountry trains.

In numerical order, the wagons are:

1 Tool Van built 1908 by the GWR.

A 4-wheel Tool Van. These vehicles formed part of breakdown trains, and carried a large selection of equipment and lifting gear. They were usually paired with a Riding Van. and based at the larger locomotive depots in case of emergency. They were vacuum-braked to permit fast running to the scene of accidents and breakdowns.

2862 Fruit C passenger fruit van built 1939 by the GWR

‘Fruit’ is the GWR telegraphic code for fruit vans – an uncharacteristically obvious code. The ‘C’ in this instance indicates that the wagon was vacuum braked and therefore suitable for inclusion in a passenger train, hence the brown livery carried.

2862 is one of 50 such fruit vans built to diagram Y9 under lots 1601/34 in 1937-9. As built they were fitted with gas lighting and with removable galvanised wire trays to carry the fruit boxes. The van was later used by British Rail for internal traffic, carrying ‘Enparts’ livery. it was preserved in 1980, initially at Bitton, near Bristol, before coming to Didcot in 1996.

3030 Rotank flat wagon built 1947 by the GWR

A long wheelbase (16' 0") wagon, designed to carry a 4 or 6 wheel road trailer. Built for Henry Edwards & Sons. The Rotank carries a Simonds Beer trailer, a famous Reading brewery.

79933 Tevan built 1922 by the GWR

‘Tevan’ was the GWR telegraphic code for a ‘special traffics’ van.

79933 was originally built as a 'Mica B' refrigerated meat van to diagram X7 under lot 890 in 1922. It was rebuilt at Swindon in 1938 to Diagram V31 under Lot 668 as a ‘Tevan’. These vans were lined internally with zinc sheeting and were used exclusively to carry tea from the J Lyons depot at Greenford and cocoa from Messrs JS Fry at Somerdale, Keynsham.

The ‘Tevans’ formed part of the nightly express vacuum fitted goods train, ‘The Cocoa’, which left Bristol Temple Meads Goods at 9.55pm for London, calling at Bristol East Depot to collect the ‘Tevans’ which had been brought in from Messrs JS Fry at Keynsham loaded with cocoa. The train was scheduled to arrive at Paddington Goods at 2.40am where the ‘Tevans’ were detached and worked by pilot engine to Fry's depot at Ladbroke Grove at 4.25am for unloading. The empty vans were worked to J Lyons depot at Greenford where they were loaded with tea and then worked to Acton where they were attached to the 1.05am Acton to Bristol express goods ‘The High Flyer’, thus completing the circuit.

82917 Pooley Workshop Van built 1911 by the GWR

This vehicle was originally built as standard covered van to Diagram V.12 on Lot 652 in 1911. In 1934 it was rebuilt as a Workshop Van on Lot 1148 (No new diagram was issued). It is one of four such vehicles built, which were used as mobile workshops by Henry Pooley & Co. to service and calibrate their many weighing machines and scales throughout the Great Western system.

This vehicle was owned by the late David Rawlinson, who based it initially at Steamport, Southport and then at Preston Dock. On his death it was bequeathed to the Great Western Society and moved to the Railway Age at Crewe in March 2004 where restoration was started under the auspices of the Society's North West Group. The vehicle was moved to Didcot in October 2008.

105781 Cone Gunpowder Van built 1939 by the GWR

‘Cone’ was the GWR telegraphic code for a Gunpowder Van. These were dust-proof vans built of steel sheet and lined internally with wood and up to a height of several feet with lead sheeting. All interior nails and fittings were of brass or copper. Great care was taken to ensure that even in closing or opening the doors there was no chance of steel contacting steel and generating a spark as all door fittings were of brass.

105781 was one of 25 similar wagons built to diagram Z4 in 1939. This vehicle was originally preserved by the late David Rawlinson, who based it initially at Steamport, Southport and then at Preston Dock. On his death it was bequeathed to the Great Western Society and moved to the Railway Age at Crewe in March 2004 where restoration was started under the auspices of the Society’s North West Group. The vehicle was moved to Didcot in October 2008.

The underframe and running gear are in generally sound condition, but the upper body, is in poor condition and will require substantial restoration

112843 Mink G built 1934 by the GWR

‘Mink’ is the GWR telegraphic code for standard box vans.

516673 and 517791 built 1942 by the LMS

These are LMS 4w Ventilated Goods Vans. Built by the LMS at Wolverton and acquired from MoD Bicester.

FRIDAY 1 JULY

Control Freak?! - Part 2

If you missed last week's instalment of our occasional series on how steam engines work, go back and read that blog as that deals with the fireman's controls on a GWR steam locomotive from the 1930s onwards. So, over to the boss's side of the cab…

4079 regulator

The most obvious control in the driver's arsenal is the large red lever in the middle of the backhead. This is the regulator, the steam locomotive equivalent of the accelerator in a car. The amazing thing about this is that the control is at one end of the engine and the valve it operates is at the other end! The regulator valve is in the smokebox. This can be a long way from the cab in the larger locomotives. Being creatures of the machine age, they are connected together in the most simple manner possible. A huge rod. You can see the far end of it in the middle of the regulator handle. It goes through a steam tight joint (or gland), passes all the way along the inside of the boiler and connects into the regulator valve at the far end.

The valve itself is actually two valves sort of laid on top of each other. The first part of the arc when you open the regulator opens a smaller valve called the pilot valve. When this reaches its fully open position, this in turn starts to open the second larger or main valve. With the handle pointed up ‘into the roof’, you have regulator fully open. With it pointed to the floor, the regulator is fully shut.

4079 jockey valve

Connected to the regulator is a linkage that operates a valve underneath it. This is known as the jockey valve. This supplies steam to the hydrostatic lubrication system via the condenser coil.

4079 condensing coil

There is a separate blog on this in the archive but simply put the big coiled pipe in the cab roof allows the steam to condense back to water but it remains at boiler pressure. This is forced into the big brass box near the driver's seat. This pressurises the thick oil that is forced up through pipes to the valves, regulator and cylinders up the front end.

4079 lubricator

The controls on the front of the brass box are little taps below small sight glasses. These control the speed at which the oil drips and is fed into the system. It is quite usual to see a piece of white paper stuffed behind the glasses to make the drips easier to see. It's usually yesterday's timetable at Didcot…

4079 blower valve

Above that are a collection of valves. The one on its own, with a spherical body, is the blower. This sends a jet of steam through a circular ring and up the chimney. This lowers the air pressure in the smokebox, gives an artificial draught through the boiler tubes and pulls fresh air into the fire – just like the exhaust does when the loco is working. It is used to stop air being forced back down the chimney when the engine goes under low bridges or into tunnels. If you think about it, a sudden blast of air down the chimney would force the fire out of the fire hole and into the cab. This could turn the cab interior into a blast furnace. With good training this is thankfully very rare. A blow back, as it is known, would not be a great situation to be in…

4079 brake valve, with vacuum gauge top right

Above that is a circular valve with a wooden handle sticking out of the top of it. This is the brake handle. The little holes in the face being where the air is let into the system to destroy the vacuum and apply the brakes. There are two other handles, one small and one large, and these operate the ejector. This is the device that creates the vacuum for the brakes and I really ought to do a blog on vacuum brakes as it’s a bit too complex to fully go into here. Above this lot is the vacuum gauge and there are two needles on the face. The right one shows the vacuum in the reservoir and the left, the vacuum in the train pipe. Think of this as the brake line and this vacuum is the one that pulls the brake off. 25” of mercury - brakes off, 0” of mercury - brakes fully on.

6023 speedometer

Moving to the stuff under the window, the use of the speedometer is obvious! The big lump with the mangle type handle is known as the reverser.

6023 reverser, showing cut-off scale 0 to 75 per cent

In car terms, it's a bit like the gearbox. No actual gears are involved however! It all done with the valves above the cylinders and the valve gear. With the indicator in the middle, the engine is in mid gear or neutral. Wind the indicator all the way forward and it will be alongside the 75% cut off mark. This means that for every stroke of the piston from one end to the other, steam is being let into the cylinder for 75% of that distance. This is the steam engine equivalent of first gear. If you left it here as you accelerate, the boiler would soon empty of steam and you would have an angry fireman on your hands!

Thankfully as you accelerate, you need less steam to keep you going. So, you slowly wind the reverser back. At 80mph on flat ground, a King of Castle with 10 - 12 coaches would be in about 20 - 25% cut off. The equivalent of fifth gear in a car. The cool thing about steam engines is that they work just as well forwards as backwards and the reverser has 75% cut off for both directions! The only limit was the tender. Fine if being pulled but a bit ‘lively’ if being pushed fast. Usually tender first workings were limited to 45mph.

6023 ATC

The box with the bell is the Automatic Train Control. This is an amazing safety system that was in another of my previous blogs – it is a truly fascinating system and worth looking at.

The last few controls are in the floor. The lever with the ratchet is the cylinder drain cocks and these are the valves that are used to clear the water out of the cylinders.

4079 cylinder cocks lever

There are two other levers – one that operates fore and aft and the other that operates side to side. These are the sanders. They open and close valves in the sand boxes to drop sand onto the rail tops to improve traction in slippery conditions. The fore and aft lever does the forward sanders and the side to side, the reverse sanders.

4079 sander levers

The theory of all of this is actually fairly simple and you can learn the basics quite quickly. However, the art of driving and firing is a very different kettle of fish indeed and doing it well is a task that can take a lifetime to achieve. In fact, it took a 14 to 15-year-old boy cleaner almost an entire career to get to the top link driver’s seat. The men that drove the Kings and Castles on the crack expresses were the most experienced men available.

40+ years old was usual for these top link drivers. Screaming along the GWR main line with 13 coaches behind you, closing in on 100mph, in charge of a mass of metal and humanity weighing well over 600 tons was a huge responsibility. Not one to be taken lightly. It may sound like an epic undertaking but dozens of express trains like these left main stations all over the UK daily in the age of steam. These men performed their jobs largely unseen by the general public, battling the elements of fire, air, earth and water and coaxing their mighty iron horses to perform to their limits. Keeping people moving and the wheels of commerce and industry turning…

Swindon drawing showing arrangement of cab fittings on a Saint class locomotive

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.