Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - August 2022 - Going Loco - August 2022

Going Loco - August 2022

FRIDAY 26 AUGUST

100 Not Out!

Well, here we are! I know there have been more than 100 Going Loco blogs, but this is my personal century. I didn’t know quite what to do to mark this milestone. It struck me that it would be great to share just a few of my personal favourite things at Didcot. I’m not doing one hundred – life’s too short for that – so I figure we will shave it down to ten in no specific order. I won’t do all locomotives so you can have fun walking the whole site trying to find them all when you visit!* So, to paraphrase Julie Andrews, These are a few of my favourite Didcot things…

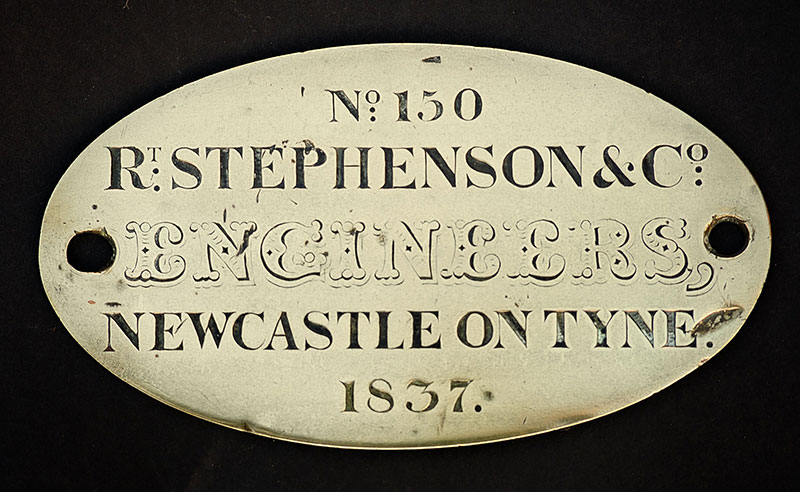

1: North Star’s Works Plate

It’s tucked away on the museum and lots of people probably just walk straight past it without a second glance but in a way, this is one of the most important locomotive relics at Didcot. It is from the first truly successful GWR steam locomotive, the original of which was sadly cut up as late as the early 1900s. For me, it’s our ultimate tangible locomotive connection with two of the most famous GWR personalities –Brunel and Gooch and the inspiration for the future GWR locomotive excellence.

2: CROCODILE F No 49134

I like this wagon because it has a story to tell. Not that all of the objects at Didcot don’t have a story to tell – it’s just that this one is really good and you can’t tell just by looking. This wagons was a prisoner of war, being taken to France by the British Expeditionary Force at the start of WWII, captured by the Germans as a result of the Dunkirk Evacuation and recaptured by Allied Forces after the Normandy Landings. I love a great story, what can I say?! This photograph shows the Crocodile carrying the boiler of No 4079.

3: Churchward 0-6-0 Saddle Tank No 1363

Ok, not easy to ‘spot’ as such at the moment as she’s in quite a few pieces in the locomotive works. If you look out the back by the turntable, you can see the black painted saddle tank, cab roof and bunker. These are all in pretty poor condition and need large areas replacing to bring the locomotive into operation again. This engine had it all thrown at it, was under threats of scrapping more than once and somehow, with the determination of some very dedicated people, it made it through. It’s our oldest Swindon-built locomotive. I also like the underdog-that-comes-out-on-top stories as well…

4: Didcot Shed DID/81E

The buildings in which we as a Society began the Railway Centre in are now unique. The largest surviving fully operational steam locomotive shed in the UK. It’s the atmosphere that it generates that I find myself time and time again pausing to reflect upon. It’s the largest exhibit at the Railway Centre and it’s one of the few places in the world left to see the sounds and sights of the working steam loco shed. The fact that we can share this with the public in the 21st Century is an amazing thing! While you look at the engines, take a moment to appreciate the surroundings.

5: The POLLEN E Girder Wagon Set.

POLLEN Es Nos 84997, 84998, 84999 and 85000 are sat with a large girder load on them. That’s how they spent the later part of their career. They were built however to transport something a little more potent. Naval gun barrels that weighed up to 120 tons. I come from a Royal Navy family (both parents) and this, coupled with the really unusual design of these wagons appeals to me. They lasted in service into the very late 20th century too. I like old stuff that continues to be relevant long after it was supposed to be obsolete.

6: George England 0-4-0WT Shannon / Jane

How could you not be impressed by Shannon? She is 165 years old this year. She is the only standard gauge survivor of the company that built her and has local links with her last job on the Wantage Tramway. There aren’t that many steam engines worldwide that are as old as her and as complete as she is. While she hasn’t steamed in many years, she still has a wonderful presence about her. Shannon’s diminutive size makes her accessible and engaging to even our youngest visitors. We may only be her custodians for the National Collection but it’s still an honour to have her under our roof.

7: Diesel Railcar No 22

What?! The steam guy likes the diesel?! Yeah, I know, but ‘The Bus’ is an honorary steam engine as far as we see it. In some ways I think we do the GWR Railcars a great disservice by calling the early BR versions ‘First Generation’. Because they aren’t. This is where the ‘modern’ diesel multiple unit first started. This machine really demonstrates just how forward thinking the GWR was and it would have been very interesting to see just where they would have gone had they not been nationalised along with the other ‘big four’ companies. They really had a vision of the future that in many ways still holds true today. And it’s a whole lot more comfortable to ride in than most modern trains too…

8: Churchward Mogul No 5322

The Old Soldier. This engine is SO important to the nation historically. She’s the sole survivor of the Churchward Moguls (2-6-0s). She’s one of only two surviving GWR Moguls, despite the type being the most numerous tender engine the Western ever built. The most import thing for me though is the WWI history it has. She is quite the potent war memorial and I can’t wait to see her run again one day.

9: Dean 6 Wheel Family Saloon No 2511**

This for me has two great things about it. First is the level of preservation in the interior compartment. I have had the privilege of getting inside and having a look more than once and you can literally smell the history! The level of originality inside, down to the smallest detail, is amazing – it’s a real time warp. Secondly is how it survived. As a house. Yep, it was a house! It’s ripe for a Going Loco in the future so, make sure that you visit 10 River Gardens, Purley-on-Thames when you visit the Carriage & Wagon Department.

10: No 4079 Pendennis Castle

Predictable? Moi? Yeah…

If you are a regular reader of the blog, you will know that I was the team leader for the overhaul of No 4079 and as a result, I’m kind of attached to the old girl!*** I have harped on about how important she is historically numerous times in this very blog but for me, she also represents the reason I started volunteering at Didcot. As a result of being a small part of her history, I continue to do things, go places and meet people I would have never thought possible. More importantly though, through working on her, I am now part of a wonderful group of people that I now call my friends. I came to Didcot for the steam engines but I stayed because of the people.

Speaking of just a few of them, it is most important for me to mention the rest of the team that don’t get to talk here! Ali and Leigh continue to be my stalwart fact checkers and Photo Frank the checker of both facts and English (he makes my weekly scribblings readable!) as well as being the purveyor of some amazing pictures and captions. Cheers to Kev for providing drawings from the archive as well as the occasional blog. Also thanks Website Rob who has recently taken up the mantle of delivering Going Loco to you digitally. Thanks to all those that have helped out with delivering Going Loco past and present too! And finally, dear readers, thanks to you for, err, reading the continuing saga that is Going Loco!

Many of the exhibits and vehicles above have been featured in previous Going Loco blogs. Why not check them out in the archive? There’s at least 100 to choose from!

*Did I just invent the Didcot version of that Pokémon game? Got to find ‘em all…

**This is the subject of an article in the Summer 2022 edition of Great Western Echo, so if you’re fortunate enough to be a member of the Great Western Society you will have already seen it. If not, why don’t you join us, or at least buy a copy of the Echo from the shop when you’re next at Didcot?

***Your blogger is seen in this photo riding on No 4079, Wednesday 24 August 2022.

FRIDAY 19 AUGUST

Personality Profiles – Sir Daniel Gooch

Photo Frank and I were having a chat the other day as to what might be the subject for this week's Going Loco. Frank suggested that there were a number of significant dates around this month associated with Sir Daniel Gooch – one of the most influential figures in the history of the Great Western Railway. So, in the spirit of an ongoing series which we will revisit now and again, here is a brief summary of the life and times of the first Locomotive Superintendent of the GWR.

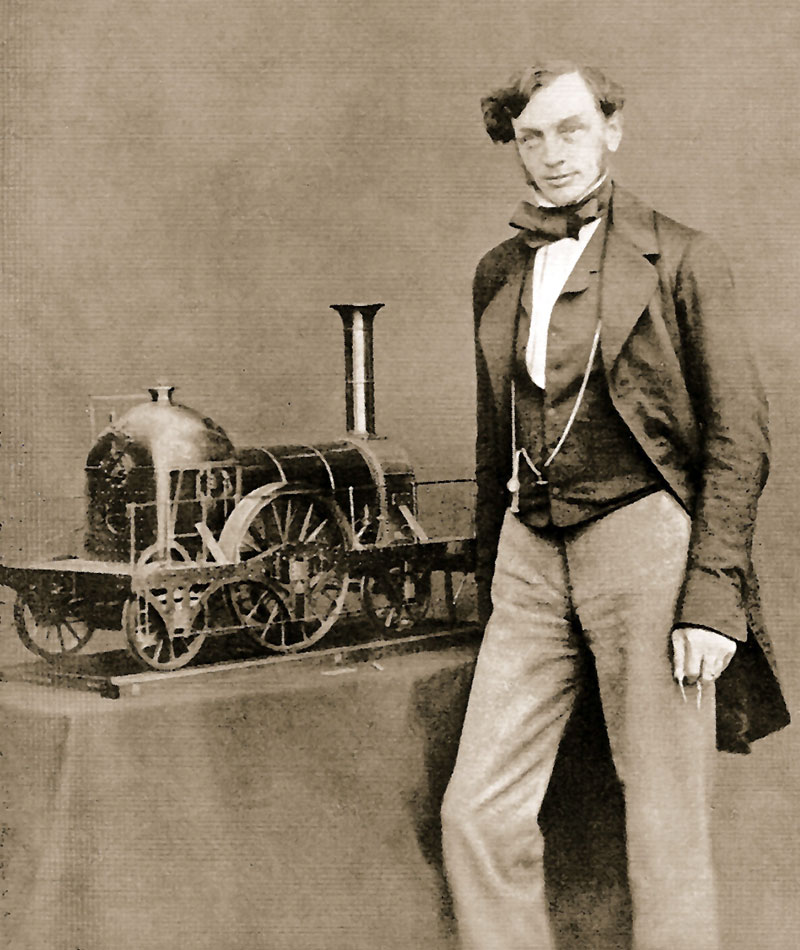

Daniel Gooch as a young man with a model of his Firefly locomotive

He was born on 24 August 1816 in a place called Bedlington, Northumberland. Quite a way from GWR territory! He was the son of John Gooch – an iron founder – and his wife Anna Longridge. 1831 saw the family move to Tredegar in Wales for John to take up a managerial post he had been offered in the ironworks there. This was where Daniel received his engineering education. In an act of massive foreshadowing, one of the people educating him was a man named Thomas Ellis Senior. Ellis was involved in the very earliest years of the development of steam railway locomotives with no less a figure that Richard Trevithick. The man who is credited with building the world’s first steam powered railway locomotive in about 1804.

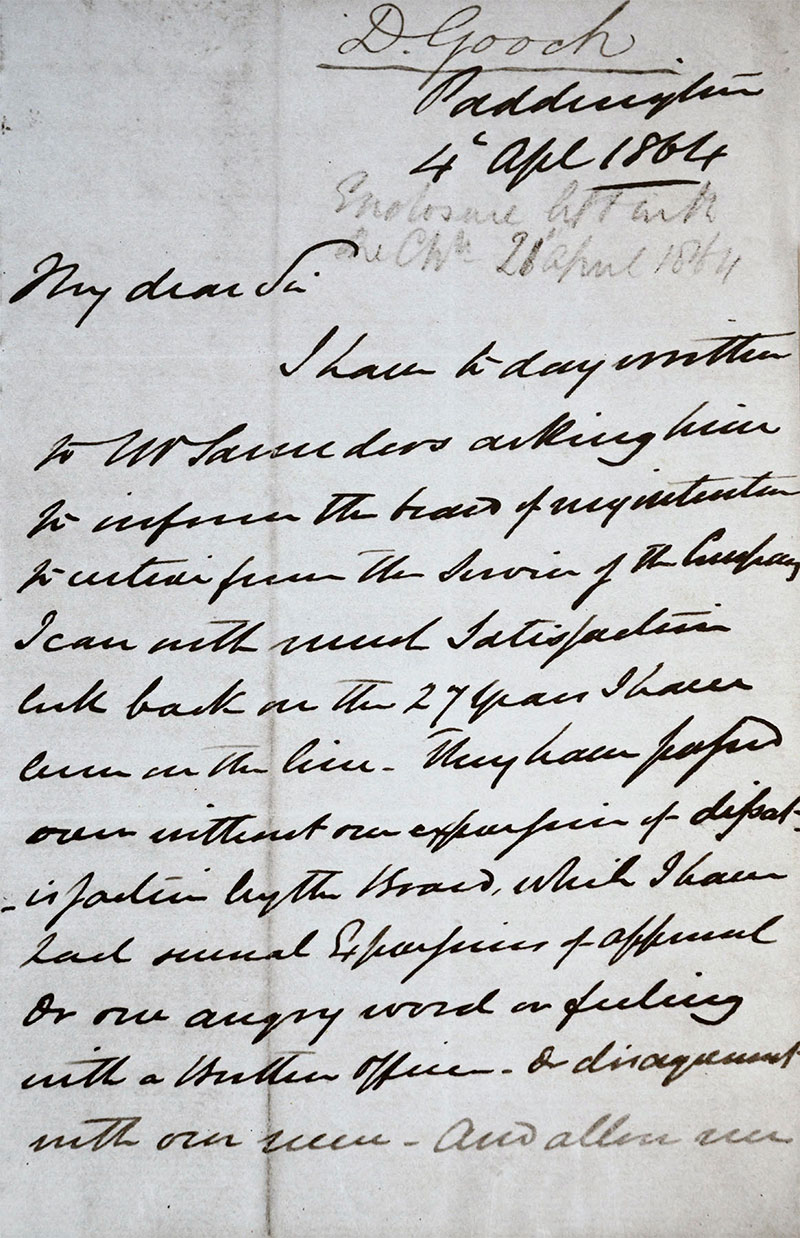

The first and last pages of Daniel Gooch’s letter of resignation to Richard Potter, chairman of the GWR, after his 27 years’ service as locomotive superintendent

Given the link to Trevithick, the fact that one of the many companies he continued his education with was none other than Robert Stephenson & Co continues to display the ‘small world’ that locomotive engineering operated in during those early years! Here, he was being employed as a draughtsman. This was in Newcastle and the other happy coincidence here was that he met his first wife while working there. Margaret Tanner was the daughter of a local ship owner. It was here that Gooch was what we would refer to today as ‘headhunted’ by a gentleman we might all of heard of, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. He became the ‘Superintendent of Locomotive Engines’ and took office on 18 August 1837. 185 years ago this week! Good blog timing, right?!*

This turned his relationship with Margaret into a long distance one for the time being but it didn’t harm it as they were married in 1838 and eventually had six children! While this was great news for him personally, his day job wasn’t going well. The motley collection of locomotives that the Great Western had purchased to run Brunel’s amazing broad gauge railway were not living up to the promise that the infrastructure offered. It was then that he had a brain wave. While at Stephenson’s, he worked on a pair of 5’ 6” broad gauge locomotives that were intended for the American New Orleans Railway. For various reasons they were never delivered. Knowing they were available, he got permission to purchase them and have them re-gauged to run on Brunel’s 7’ 0¼” system.

The two locomotives – North Star and Morning Star were subsequently delivered. They did nothing less than revolutionise the operations on the GWR. Brunel and Gooch worked together on their draughting (the flow of gases through the fire and up the chimney) to improve their efficiency, and a standard was set. Gooch took the lessons learned here and designed his new engines, the Firefly class of 2-2-2s. They were introduced in 1840 and proved themselves even more capable that the best of their standard gauge rivals. He also developed his own design of valve gear to use as well.

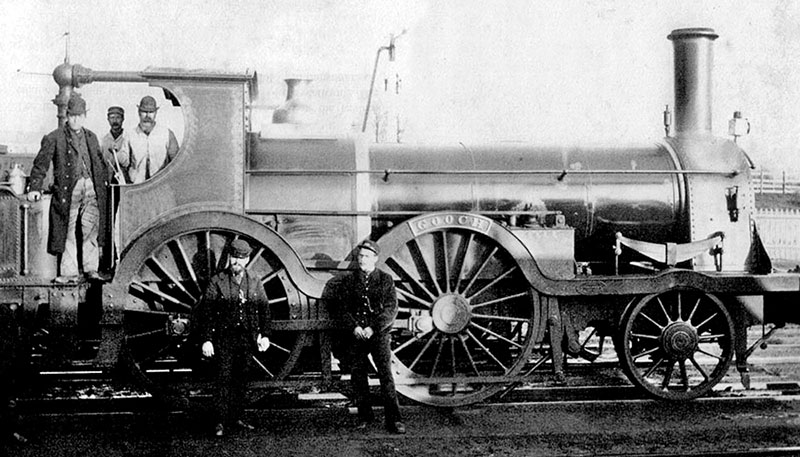

The Hawthorn class locomotive Gooch, built in 1865 and designed by George Armstrong who succeeded Daniel Gooch as locomotive superintendent

Another of his achievements at this time was the siting of the main locomotive works of the Great Western at a little place called Swindon in Wiltshire… The first fully ‘Swindon’ locomotive that was produced there was the prototype Iron Duke Class locomotive, appropriately named Great Western. Completed in 1846, these machines were capable of 70mph. Motorway speeds today but a transport revelation then. He worked on producing many designs for the broad gauge and even designed some machines for the new standard gauge northern section of the railway in the 1850s and 60s. He resigned at the height of his powers as locomotive engineer in 1864 but he retained a position on the company’s board of directors.

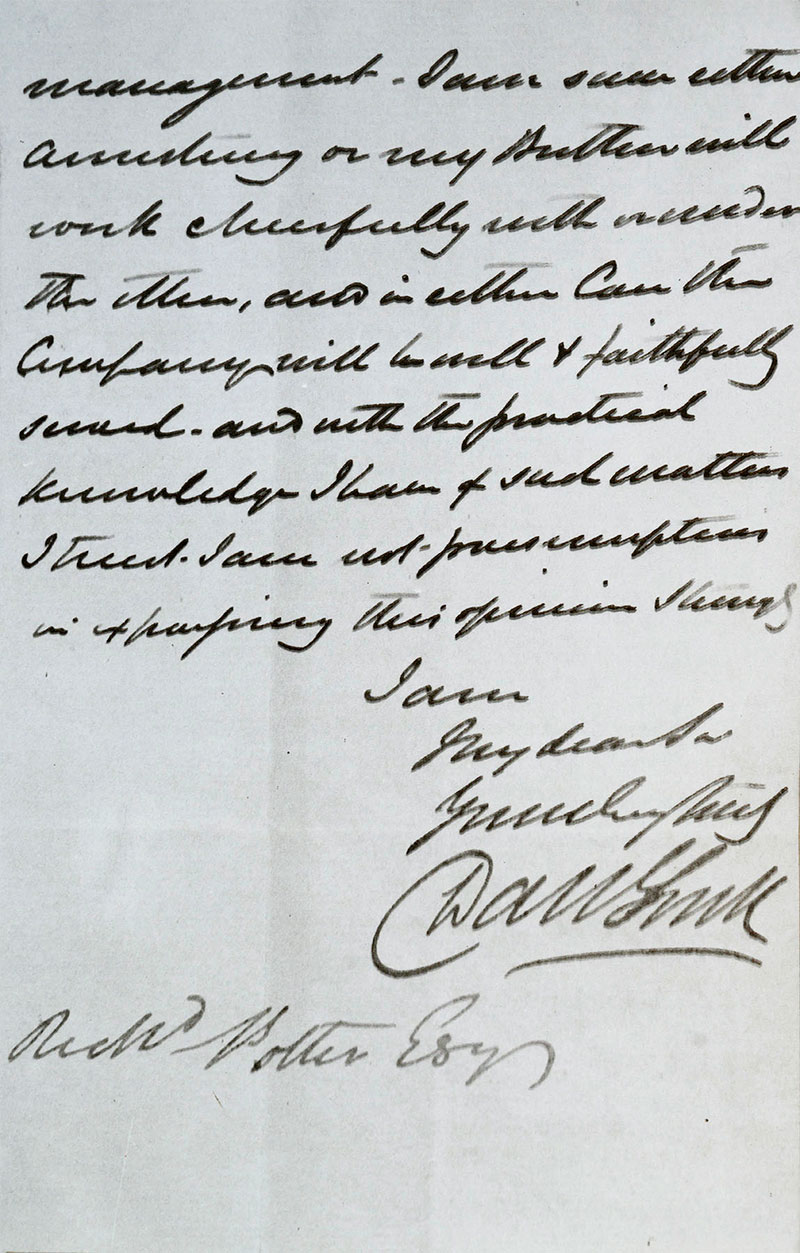

His engineering exploits continued, however. In 1865 he joined the exploits of Brunel’s last great work, the mighty ship, the PSS Great Eastern. This ship failed as a passenger vehicle but was perfect for laying the first ever successful transatlantic telegraph cable. Remarkably, while out of the country on this vastly influential project, he was elected to parliament as a Conservative MP for Cricklade. All whilst being recalled to the GWR in 1866 as its chairman. Here he saved the company from near bankruptcy and later was involved in the building of the Severn Tunnel. Oh, and he was made Sir Daniel by becoming a Baronet the same year, 1866, as he became GWR chairman.

The arrival of the transatlantic cable in Newfoundland after being laid by the Great Eastern

If 1866 was his year of ultra achievement, 1868 was decidedly the curate’s egg. He did become the chairman of the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company but sadly his wife Margaret passed as well. He was alone for two years but eventually married again to Emily Burder in 1870. He passed away on 15 October 1889 at the age of 73. He and Emily had no children but she outlived him, passing away with the end of the Victorian era in 1901.

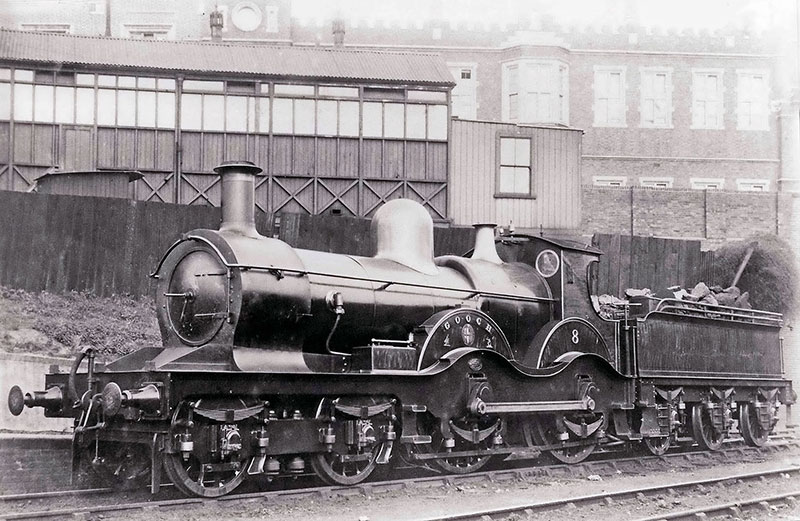

The 4-4-0 No 8, named Gooch, built in 1894

Sir Daniel Gooch was an incredible individual, a real product of the white heat of the Victorian era and its advancing technology. He was instrumental in not only the transport revolution but was a key figure in laying the foundations for the Information Age we live in today. A man we have much to be thankful for in this and other countries around the world. He helped bring us all together and make it all that little bit smaller…

I couldn't finish without this quote from the man himself. He held his seat in parliament until 1885. He never addressed parliament and wrote in his diary upon the dissolving of parliament that year that: “It would be a great advantage to business if there were a greater number who followed my example…”

The 7¼ inch gauge model of Gooch now displayed in the museum at Didcot Railway Centre

*This is entirely down to the work of GWS founder member Mike Peart who researches and compiles an ever-expanding Word document: The Great Western Railway, day-by-day through the ages – a compilation of dates, facts and stories about the GWR. This now contains more than 300,000 words – about the same count as Charles Dickens' The Pickwick Papers but only half way to Tolstoy's War and Peace at 600,000 words! Mike's research is the prime source for the On this day in history posts on Didcot Railway Centre's Facebook page.

FRIDAY 12 AUGUST

For Those About To Roll – Fire!*

There are a few fundamentals when we look at the operation of steam locomotives. When passing the footplate, the one thing all the parents point out to their children is the fire. The children often fall into one of two camps. Either abject terror – we teach children to be wary of fire so it’s understandable – or total fascination. The parents often give the explanation to the children that: “you put the coal in there and that makes the train go”. If only it were that easy…

In the cab of City of Truro during a visit to Didcot some years ago

First, the science. You may remember from your school lessons that the teacher waffled on about something called the fire triangle. This is the three things that are needed to allow a fire to ignite and to continue to burn. Each side of the triangle represents one of the three key components. Remove any one and the fire goes out. The first component is the fuel. A fuel is defined as a material that can be made to react with other substances. When this reaction happens, it releases thermal energy. This thermal energy can be used to do useful work – be it the petrol or diesel in a car engine or the coal in a steam locomotive.

A tub of good quality coal in the coal stage, 31 August 2020

Most of the stuff that makes up coal is in fact carbon – 75% of it on average. Another 10% is ash. The last 15% is various gases and small amount of sulphur and other stuff. To get the coal to even consider igniting, it needs to be heated to 800 degrees Fahrenheit. Heat is the second part of the fire triangle. In order to get the fire there, a locomotive has to start on something a bit easier to get burning. It’s usually paraffin-soaked rags. These are lit and then placed on a pre-prepared bed of wood. Once this has ignited and has been built up, you can then start to add the coal in thin layers to allow it to rise to the 800 degrees F needed to start its combustion.

On a large loco like No 2999 Lady of Legend or No 4079 Pendennis Castle, a warming fire of wood will be lit in the firebox the day before, although this is to allow the boiler to heat up slowly. Large riveted pressure vessels like the boilers don’t like to be heated in one place and be cold in the other. It makes the different plates that make up the boiler twist against each other, opening seams and causing leaks. More of this later.

While the coal stage has been out of use for water tank conservation, an alternative method of coaling has been used

While combustion starts at 800 degrees F, coal combustion at this temperature is really poor. Not all of the volatile materials are properly consumed and they escape up the chimney unburnt as smoke. It requires temperatures north of 2,500 degrees F to get to a point whereby the coal is burning really efficiently. The difference in temperatures mean that up to 70% more heat is produced. With the heat and the fuel taken care of, it’s the regulation of the supply of air (actually the oxygen - fire triangle part three!) that makes the difference between 800 and 2,500 degrees…

There are two ways that air can get into the fire. The first – known as primary air – comes in via the ash pan and up through the fire bars. The volume of air flowing up through the fire is controlled by doors on the end(s) of the ash pan. The number of doors depends upon the size and shape of the locomotive. No 1340 Trojan only has one rear door whereas, due to the fact that the bottom of the ash pan is split in two by their rear driving wheel axles Nos. 2999 & 4079 have four doors. Front front, front rear, rear front and rear rear(!). Secondary air enters the fire from the firehole doors and these can be opened and closed as required. As the doors on a GWR loco are quite heavy, there is also a flap that can be raised and lowered on a chain if frequent firing is needed.

Firing Castle class No 5082 Swordfish at speed on the Cambrian Coast Express, August 1957. Photograph by Kenneth Leech

The aim is to get the smoke coming out of your chimney to be light grey. Too little air and the smoke goes black. This is due to incomplete combustion of all the volatile matter in the coal. This can lose the loco as much as 11.4% of the heat it could be generating. Far too much air (causing almost ‘clear’ smoke) is just pulled through the fire. This plays no part in the combustion of the fuel but does cool the fire down. As much as 3.1% can be lost here. The hot gases run along under the brick arch in the fire box and this, along with the extra turbulence caused in larger engines by the baffle plate above the fire hole door, fully mixes the air and volatile gases, allowing them to fully ignite and then be drawn through the tubes in the boiler to heat the water and produce the steam.

So, bung some coal on the big flame thing in the hole and give it a bit of air and we are good to go right? Well, no, it’s a bit more complicated than that… The coal needs to be the right size to start with. Too small and it just falls through the fire bars and clogs up the ash pan, denying the fire some of its primary air. Too large and only the outside burns, leaving the inside untouched, causing cooler spots in the fire. It’s all about surface area. The more surface area there is, the more that the volatile stuff can burn. There’s a sweet spot with size!

We also need the coal burning in the right place and at the right time. If there is a hole in the fire, the cold air drawn up from the ash pan isn’t heated and it both cools the fire and runs the risk of differential heating of the boiler plates, causing the aforementioned boiler leaks. If you just lay on a thick layer of fresh coal, it reduces the amount of burning coal and lowers the heat of the fire. It is known as blacking the fire out. If you look in the firehole door, the fresh coals show up as a dark area because it hasn’t ignited yet. Hence the name.

During a test run of Pendennis Castle from Didcot to Reading in January 1967, fireman Kevin Pierpoint uses the pricker in the firebox. On the left in his special seat is the locomotive’s then owner Bill McAlpine

The fire needs to be hot and producing steam at the right time. Sat in the yard, the fire needs to be cooler, not raging hot and causing the safety valves to lift and wasting energy. Pulling a heavy train up a hill needs a lot of steam. The coal you put on does not ignite immediately, it takes time to build heat. Therefore the judgement as to how much coal to put on and when is where the science turns to skill and it can only be a skilled fireman that gives the driver the steam that they need, when they need it.

Poor air provision (and sometimes poor fuel) can also result in clinkering. This bubbly ceramic like deposit** is due to the sulphur in the coal being found as a compound of iron called iron pyrites. If these residues are not driven off and up the chimney or dropped into the ash pan, they can sit on the fire bars, mix with ash and cause the clinker. The clinker blocks the gaps between the fire bars, starving the fire of air. This makes the clinkering worse and around we go again…

The footplate crew at work near Goring in February 1934

As you can see the science and techniques used to fire a locomotive are quite complex. Don’t forget that the fireman is also trying to keep the water levels in the boiler up (too much water at once cools boiler too) and act as a second set of eyes for the driver. The GWR kindly put the signals on the left and the driver on the right of the cab. Why? It was the way they had always done things. The message here I guess is that everything in the fire needs to be just right. Not too much or too little fuel, air or heat. Which makes it a bit like a really industrial version of Goldilocks and the Three Bears…

*With apologies to AC/DC.

**The G.W.R. Used ash and clinker as ballast in sidings and as a fill in material. If you look around the site at Didcot, you will easily find a rock that looks a bit like the inside of a Crunchy chocolate bar - that’s the clinker.

FRIDAY 5 AUGUST

Brown - Part 4 - Fruity? You Must Be Bananas…

In our continuing brown vehicle quest, we have looked at several types but the most common factor noted has been the low production numbers. This is the same for the vast majority of brown vehicles. The jobs they did were not that common, meaning that not many were needed to cover the small amount of traffic that they were designed to satisfy. As with all rules however, there is always an exception…

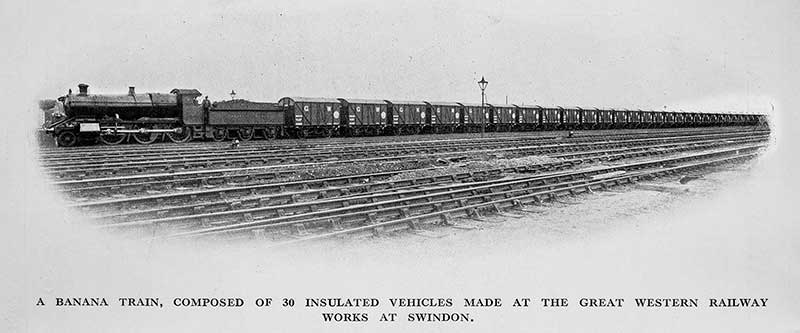

Published in GWR Magazine March 1923

Diagram Y on the wagon index is where these vehicles live. Although still not vast amounts of vehicles by steam age standards, the total of about 1,250 wagons is still quite impressive for the brown vehicles. Their telegraphic code name gives the game away with regards to their use. The FRUIT vans were originally designed to carry fruit(!). The other thing to know about these 1,250 brown vehicles is that some of them weren't brown vehicles. Let me explain…

There were a couple of different types of fast goods trains. The stock was labelled accordingly. GOODS FRUIT vans were not to travel at full passenger train speeds and PASSENGER FRUIT vans were. The former were painted standard freight grey and the latter were brown*. When not carrying fruit – understandably this ebbed and flowed in different growing, harvesting and importing situations – they were used for carrying parcels. Their high speed ratings making them useful for this purpose. High speeds meant that these vans had vacuum brakes rather than having just a handbrake like the majority of UK steam era freight stock. The other key feature that makes many of these vehicles an easy ‘spot’ are the ventilation slats in their sides to allow airflow around their cargo. We are really lucky at Didcot in having examples of a wide range of the FRUITs and a chronological look will effectively tell the story!

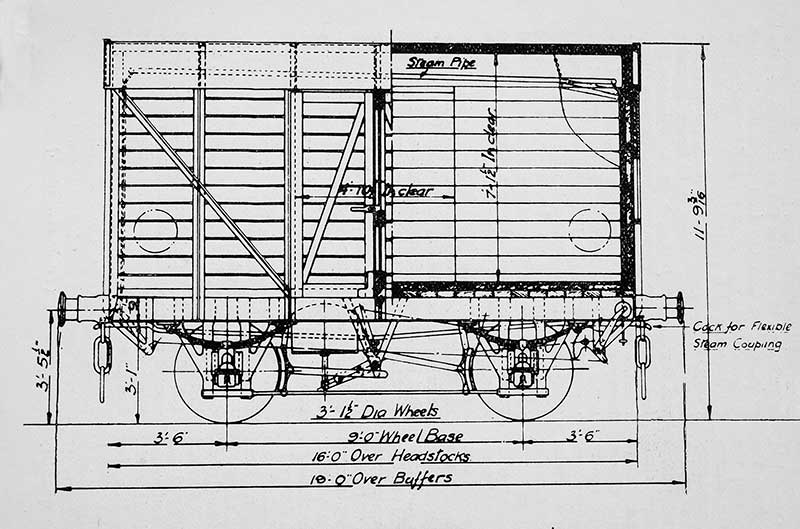

The drawing of a banana van published in the same edition

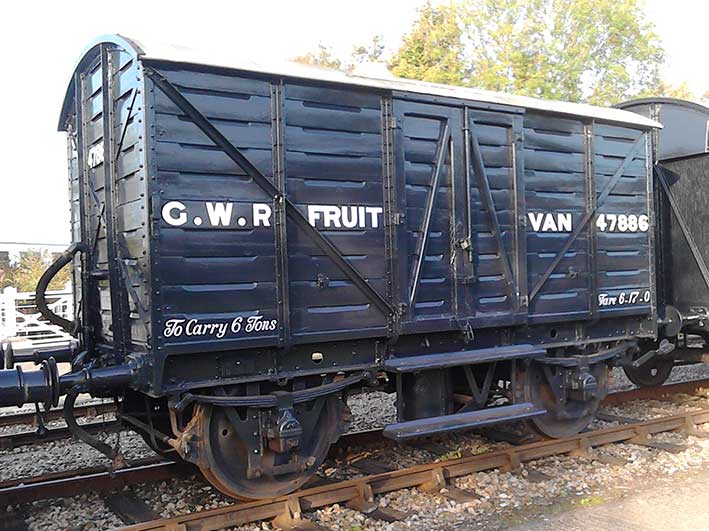

The first is a van to diagram Y.2. It is one of the oldest freight vehicles in the collection.

No 47886 was built way back in 1892 to lot number 638. This design was 16’ long with a short 10’ wheelbase. The arrangement of ventilation on these wagons shows the development of the idea. Firstly they were just at the top rows of planks on the body sides. This was extended downwards in later vehicles and there was even a version that had gaps between the floor planks… Like a lot of vans, there were end ventilators too. These came in several varieties. Triangular cross section hoods and openable sliding vents were seen in different combinations on all the FRUITs.

Other interesting features about No. 47886 are the unusual Dean era vacuum brake system where the cylinder moves up and down instead of the piston. It also has a cylindrical chimney type apparatus on the roof and this is for the oil lamps fitted. All mod cons here you know. One really obvious thing about this vehicle if you look at it right now is the fact that it’s a grey painted vehicle and not brown. This is a livery from its early life – about 1904. The long 5 digit number is more typical of grey vehicles too. The Y.2s were only accepted into the brown vehicle series in 1913 and our one was renumbered to No 2356. It has worn this livery and number in preservation in the past and as a vehicle that can carry both liveries – why not? Of course, the 1913 brown vehicle livery was crimson lake. Perhaps that might be the next coat of paint?

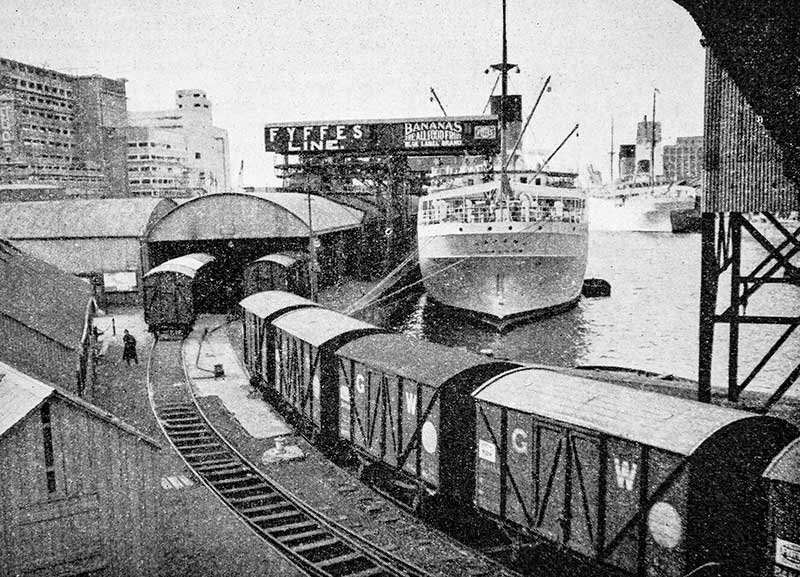

Our next Diagram Y vehicle is to diagram Y.6 and this is one of the grey fast goods vehicles rather than the express passenger goods vehicles. This one is completely bananas. Literally. The importing of bananas was big business for the GWR. These vehicles were sometimes classified as FRUIT B and were different to their fellows in that ventilation was the last thing the bananas needed.

The Banana discharging berth at Avonmouth docks was published in GWR Magazine April 1939 edition. Unfortunately this one in the library is not the version printed on art paper

Quite the reverse. These vans were insulated to protect the tropical fruit and in later years were fitted with steam heating. The idea being that the fruit (shipped across the oceans in a green state) would be encouraged to ripen en-route to be what we know in supermarkets today as ‘ready to eat’.

Ours is No 105599 and was built at Swindon in 1929 to lot 1054. Apart from the word BANANA** written on the side(!), the other key indicator of its purpose was the large white circle painted on the upper right of each side.

The FRUITs got progressively longer as time went on. The next in our virtual fruity tour is No 2862.

This is a FRUIT C and was one of 50 built to diagram Y.9 as part of a couple of lot orders in the late 1930s. Ours first saw the light of day in 1939. They were first known as FRUIT C and FRUIT D. The difference being that the D variety were fitted with both vacuum and Westinghouse air brakes. The Cs just had vacuum brakes. This causes a bit of confusion because after the air brakes were removed, the classification FRUIT D was reused for another type of vehicle. The first versions of these FRUIT Cs were built in the early 1910s. These were 10 tons in weight, were 22’ long and sported a 12’ 6” wheelbase with two double doors per side. No 2862 was used until the late 1970s, finding employment as an ‘ENPARTS’ vehicle. This was British Rail’s naming code for a vehicle that was being used to transport locomotive spares.

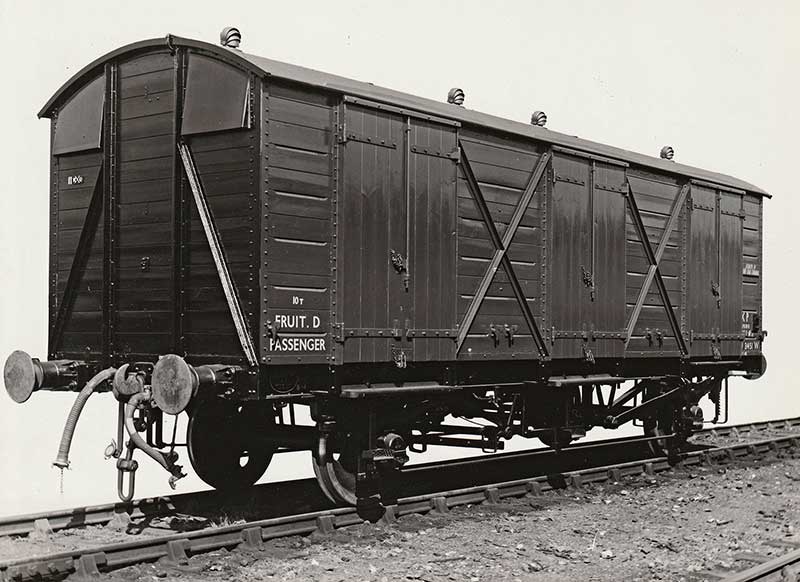

The final incarnation of the fruity family was the FRUIT D.

An official picture of a Fruit D

The last and largest were 28ft 6ins long with an 18’ wheelbase and three double doors per side. These are to diagram Y.11 and ours - No 2913 - was part of Swindon's wartime production in 1941.

These were as equally long lived as the FRUIT Cs and continued in service long after the end of the GWR. In fact, the design was deemed so useful that British Railways built another batch of them in the early 1950s. The tradition of the 4 digit numbers continued with the reuse of some of those from earlier scrapped FRUIT vehicles. No 2913 is the only one of our FRUIT vehicles yet to be restored.

Again, the staying power of these vehicles is remarkable. It was really only the phasing out of vacuum brakes and the toll that time was taking on their wooden construction that ended their reign. From a highly specialised origin, a great series of generalists were born and this enabled them to take on all manner of tasks, helping to keep the nation moving for many decades. The type has clearly more than earned its place in our collection!

*Except when they weren't. See the first in this series for a full explanation!

**There was another type of text applied to some of these wagons with the wonderful words ‘STEAM BANANA’ on their sides. I've always wondered if a steam banana needs a boiler certificate…

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.