Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - November 2022 - Going Loco - November 2022

Going Loco - November 2022

FRIDAY 25 NOVEMBER

The Sleeper Agent

There is an unsung hero at Didcot that needs to be recognised. An old soldier that has neither died in battle or, as is traditional (apparently), faded away. It goes about its business, doing its own thing trundling backwards and forwards, helping to keep the society and the railway centre running. Did I also mention that it’s one of the oldest freight vehicles in regular service on the national network?

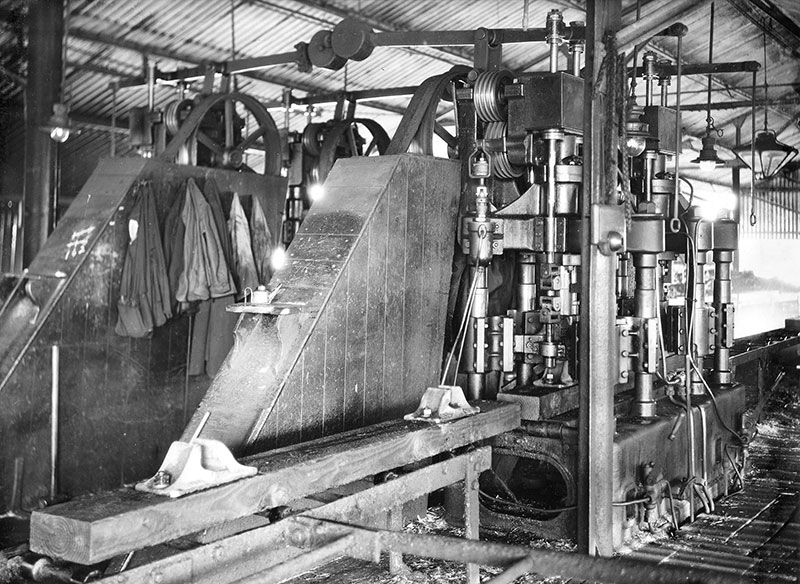

A general view of the Hayes Creosoting Works. This is part of a remarkable album of photos taken by GWR photographers in 1934 and bequeathed to the Great Western Trust by Peter Lugg, who was a senior permanent way engineer for British Railways

When you lay railway track, you can’t just plonk the rails on the ground. They need to be held level and secure. This is particularly important for maintaining the gauge of the track. This is defined as the distance between the inner faces of the rails that the train runs on. In the earliest days of railways, the rails were mounted on stone blocks. These were just mounted under a single rail and when the advent of the steam locomotive occurred, the extra weight tended to push the rails apart. Not good as this makes things fall off the track.

Unloading sleeper timbers from a canal barge at Hayes, from Peter Lugg’s album

Wooden sleepers – or ties in American parlance – were the answer but Brunel went down a slightly unsustainable route when he first engineered the Great Western Railway. Instead of the picture that you have in your head right now, reading this, of sleepers at right angles to the rails, stretching off into the distance, he put his sleepers longitudinally under the rails and used a series of tie bars of either wood or wrought iron to, er, tie the two rails together and keep them in gauge. This was known as the baulk road and it was said that at speed, it had a rather sinusoidal up and down motion as you went along. Of course, less connections between the rails meant exactly the same issue – gauge spread.

One of the creosoting depot steam cranes stacking timbers for seasoning, from Peter Lugg’s album

So, eventually, the GWR ended up with not only the same style track as everyone else but also track spaced to the same gauge! The practice of laying wooden sleepers at right angles to the rails became standard pretty much worldwide. The sleepers were made from a wide range of different timbers including softwoods like baltic pine from Russia or douglas fir from the USA and Canada. Then eucalyptus (jarrah) timber took over as it was more tough and ideal for level crossings and hard wear locations.

Closing the door on a stack of new sleepers in the creosoting cylinder. Photograph on the cover of the British Railways Western Region Magazine, September 1948, taken by Harold White FIBP, FRPS

The GWR treated sleepers in a large plant at Hayes in Middlesex, opened in 1877. A wharf by the Grand Union Canal enabled timber and components to be offloaded from barges by the depot’s five-ton steam cranes. The site was re-modelled in 1934/5 and was able to store 750,000 sleepers for seasoning, and process up to 500,000 per annum. Sleepers were loaded into creosoting tanks, the air in which was drawn out by vacuum pump before creosote was fed in under pressure. Once treated, having absorbed up to 3½ gallons each, the sleepers would last for around 20 years. Creosote is a somewhat ferocious mix of the stuff given off when fossil fuels aren’t fully combusted and the sort of chemical that will, at least temporarily, put off even the hardiest of insect attack

Rail chairs being loaded onto the conveyor to be fitted to sleepers, from Peter Lugg’s album

The process of fixing the rails to the sleepers is different the world over. The American railroads for example prefer a method that uses spikes. These are large nail type things with an off-set head that grips the rail and pins it to the sleeper. In the UK, a rather more technical process was adopted. Cast brackets called chairs have a slot in them for the rail to fix into. A device called a key locks it in position. The chair is bolted down to the sleeper with some fairly hefty fasteners. So why is all this relevant to our story today? Well, it’s all about the wagons that live in T Diagrams.

Chairs arriving in the shed to be fitted to sleepers which already have fang bolts in position, from Peter Lugg’s album

Just as the GWR had specialist vehicles for a huge range of different goods to be safely carried, this specialisation carried over to the rolling stock that were used by the various maintenance parts of the organisation that kept the whole thing working. These ‘Departmental’ vehicles were sometimes recycled old stock. For example, old passenger coaches were used to transport men and equipment about the network to job sites. Indeed, a fair proportion of the coaches at Didcot survived long enough to be preserved via this mechanism.

The machine for tightening nuts onto the fang bolts, from Peter Lugg’s album

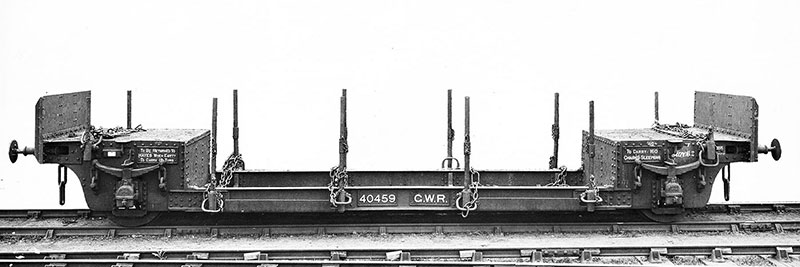

At the other end of the scale we’ve got the highly specialised vehicles that did one thing, really well. The Diagram T wagons were specifically used for transporting chaired sleepers and signal posts. The very definition of departmental! We are looking at the T1, T12 and T13 designs. The design was that of an 18 ton well wagon with removable stanchions to allow for loading. Along the edge of the dropped edge of a well are pockets for storing chains and shackles. The first batch only had a handbrake and 101 were built in the closing years of the 19th century.

A specially-designed sleeper wagon, photographed in June 1917, from Peter Lugg’s album

These wagons were designed to carry chaired sleepers. That is sleepers with the rail chairs pre-attached, ready to drop into a job site to lay new track. A further batch of 18 were built just prior to WWII. They were slightly longer and were fitted with vacuum brakes as well. Our wagon comes from this batch. No 100682 was completed as part of Lot 1313 in 1939. A final batch were built between 1942 and 1944 and the final difference was the lever brakes in place of the Dean/Churchward ratchet handle.

A specially-designed sleeper wagon with full load photographed in June 1917, from Peter Lugg’s album

A few of these wagons, No 100682 included, were purchased by the Taunton Concrete Company. They performed a few modifications on the wagon, including the addition of the removable wooden sides. From there, the wagon was purchased by the Great Western Society. As a preserved wagon, it’s a GWR classic; it’s one of a small batch and it’s really quite an interesting vehicle. Except retirement never came. The wagon is fitted with a through air pipe to enable it to work with air-braked stock on the modern railway. It’s been renumbered to No GWS 91200 and on it goes. The wagon is still a vital part of the running of the centre, it’s low floor allowing for tall objects to be transported. At 83 years old, it’s got to be one of, if not THE oldest freight vehicle still on the network in regular service. Unless you know better…

Didcot Railway Centre's No 91200, modified with wooden planked sides by Taunton Concrete Works

FRIDAY 18 NOVEMBER

The Special Branch?

There are quite a few vehicles in the passenger coach collection at Didcot that were built to serve a very exclusive market. We have already had a chat here on Going Loco about the Super Saloons and the Dean family saloon. There is however another vehicle in this set that has been on constant public display since I started writing these blogs. We had better do something about her, I suppose…

9002 on the carriage shed traverser, showing off her six-wheel bogies

The conveyance of the well-to-do was at the forefront of the GWR's thinking since its inception. Queen Victoria is famous for her journeys on the line between Windsor and Paddington. For this, she had her own special coach built. The first time she travelled, it was said that she found the speed terrifying and henceforth a special signal was fitted to her coach that she was able to use if she thought progress was a bit rapid! The amazing thing about those early royal services was the loco crew. The engine was often driven by none other than Daniel Gooch (the GWR's first locomotive superintendent) and he was accompanied by a chap you might of heard of – Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

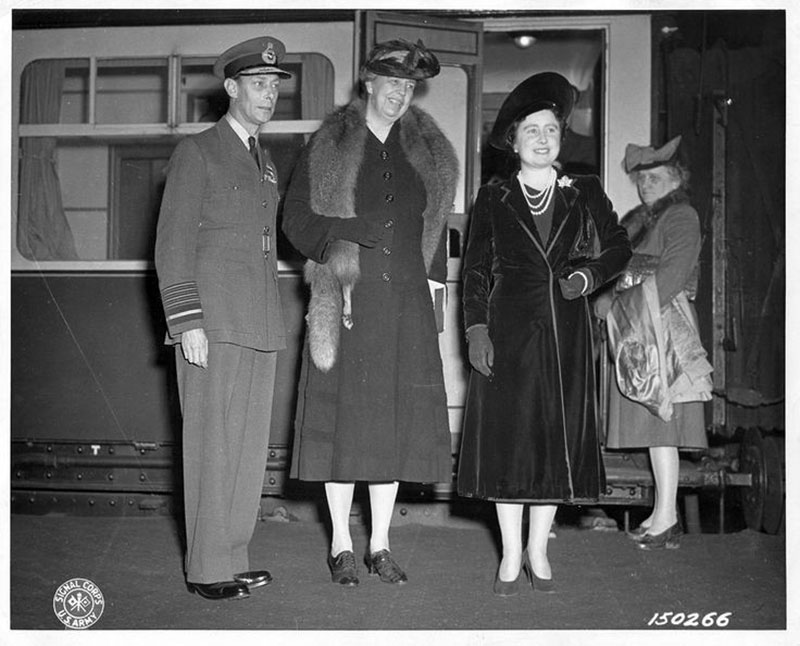

Eleanor Roosevelt (centre) First Lady of the USA, is welcomed by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on arrival at Paddington station on 23 October 1942, having travelled from an unnamed airport in the west country in one of the saloons, 9001 or 9002

The production of coaches at Swindon was not as standardised as the production of locomotives. There was a fairly eclectic bag of vehicles that were built to a multitude of different designs. This was always an issue and meant that as time went on, the administration of the fleet became harder and harder. In 1907, the world decided to do something about it. The whole fleet was rearranged and organised into a new series of diagram letters and were renumbered to help with identification.

This photograph was published in September 1944, and shows the original interior décor of 9002. The caption in the magazine reads: “The above photograph is of GWR coach No 9002 – the private saloon used by a number of distinguished personages. The Murphy set is an A92, fitted in a specially built console and slightly modified for increased output.”

The renumbering went like this. Most coaches had a three-figure number. The Third class carriages were left alone but each of the other types had a prefix added to them. For example, composites had 6000 added and first class had 8000 added. The other thing done was to organise each of those groups into a letter diagram – just like the wagons. Therefore, our Dreadnought all third coach is to diagram C24, the C standing for all third class bogie coaches.

Dr Richard Beeching, Chairman of the British Railways Board, and Stanley Raymond, General Manager of the Western Region, inside 9002 on 24 June 1963

Diagram G is where we are looking today. This was used to put all of the vehicles that came under the heading of saloons. These vehicles are best described as mobile luxury apartments. They are self-contained and have plush seating compartments, a private toilet, a small kitchen and pantry of some descriptions and a small staff to look after the travellers. Quite frankly, it is the only way to travel…

The lounge of 9002

Not all the coaches under diagram G had all the facilities mentioned but it’s a good rule of thumb. Due to their highly specialised use, they were also never very numerous. Rare beasts even when built. This is true of the subject of today’s blog. Remarkably for wartime, this coach was built during WWII. Why is this remarkable? At the time, there was a ban on building anything that might be seen as ‘luxury’. Certainly, the construction of last two Castle class engines of the pre-war batch, Nos 5098 and 5099, was halted until the end of hostilities. Quite how the special saloons Nos 9001 and 9002 were built in 1940 therefore is a bit unusual to say the least.

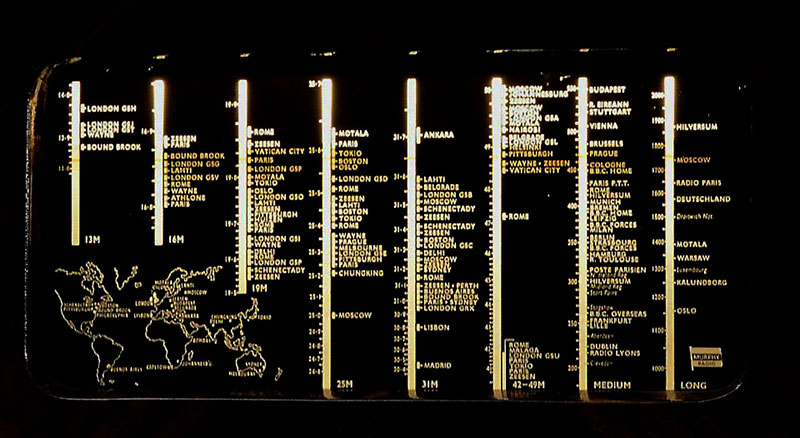

The radio dial showing the stations that can be received on the Long, Medium and six Short wavebands

Our coach, No 9002 is built to diagram G62 as part of lot No 1626. She was completed in 1940, as described above. Perhaps construction was sufficiently advanced to make it easier to finish them and get them out of the way rather than stop and store them. The early history of these vehicles is a little murky at best! The coach itself is a bit of a beast, weighing in at 42 tons. This is partly a result of the six-wheel bogies to give a smoother ride. She has a coupé at one end, a small compartment with plush seating. Next comes the lounge, then the lavatory, next the dining room, followed by the kitchen, pantry and attendant’s seat.

Princess Anne during her visit on 27 May 2003 to launch 9002 after restoration was completed

There is a really quite fascinating rumour concerning this coach. Having a resource like No 9002 and given that there were a vast number of VIPs – both civilian and military – travelling the country for a multitude of reasons, it stands to reason that you would use the coach for this purpose. Given this, the rumour that the coach was used by General Eisenhower during the preparation for D-Day is not without merit. Given the secret nature of the build up, the lack of documentary evidence in this point is understandable.

James Braxton and Natasha Raskin Sharp in 9002 during filming of an Antiques Road Trip episode on 7 November 2021

The coach does display a number of key features not normally found on GWR saloons. While she does have the (then!) latest of on-train entertainment in the form of a radio, something about its aerial doesn't ring true for being a device for simply picking up the BBC. It's huge. If you can step back safely and look up when you stand next to No 9002, you will see a long, thick wire running a good proportion of the length of the coach. The body of the coach is also electrically bonded to the chassis. All odd things and not part of the regular design of a Swindon coach – even a saloon.

The dining table of 9002, which can also be used for board meetings

We do know however that after the war, she became part of the GWR's Royal Train. In the early 1950s, No 9002 was taken back from her home in the carriage shed at Old Oak Common to her birthplace. The interior was modernised with beautiful tiger's eye walnut on the walls of the saloons. Burr walnut veneer was used on the table and the light fittings. The upholstery was refinished in a pink check with matching pink curtains. The vehicle was then marketed as a boardroom on wheels for companies to hire when their directors were visiting factories. It was also used for Royal visits – notably in June 1965 when The Queen travelled in No 9002 from Victoria to Tattenham Corner for the Derby. The Royal Train on that occasion included three Pullman cars in addition to 9002, hauled by Southern Railway electric locomotive No 20002.

The coffee machine inside the kitchen of 9002

No 9002 has been extensively restored and has been fully rewired to modern standards. The steam heating was replaced with electric heaters but these have been hidden under the original grilles. All of the veneer was stripped back and re-varnished. The seats in the saloon and the coupé have been re-upholstered in traditional GWR material, replacing the BR 1950s pink. When the saloon was finished in May 2003 she was honoured by a visit from Princess Anne to relaunch her.

No 9002 now stands as a double tribute: firstly to the skilled hands that built and maintained her and secondly to the equally skilled hands that restored her. She really is the pride of the Carriage and Wagon department and make sure that you take the time to see her when you next visit.

FRIDAY 11 NOVEMBER

The Rat

We've had a look at both the Class 14 Teddy Bear and the Class 08 Phantom so far in Going Loco. However, there is another diesel shunter in the collection. She's not often seen in use by the public and is actually an industrial version of a British Railways class. She also has a rather interesting nickname. She's called The Rat.

DL26 in November 2022

The origins of this locomotive begins with the Hunslet Engine Co. The company was founded in 1864 at a works at Jack Lane in the Hunslet area of South Leeds. Here, a locomotive works was established by John Towlerton Leather. The works was famous for its industrial locomotives and its narrow gauge engines were also very popular. Two of the steam-powered products they are best known for are the 4-6-0 narrow gauge locomotives used on trench railways in the Great War and the ubiquitous 0-6-0 Austerity saddle tank design that was produced in quite some numbers during the Second World War.

The design we are interested in today however is a diesel locomotive. The class 05 is another of those designs that were part of the poorly-thought-out modernisation plan that began in the 1950s under British Railways. The modernisation plan did one thing really well. It sought to replace all the roles that were performed by steam engines with diesel and electric machines. There were two issues with this. Firstly it was rushed, there were designs that were ordered straight off the drawing board. No prototypes, no testing, nothing.

The gear change controls of DL26

Thankfully, the class 05 was quite good from the get-go. This design was an 0-6-0 shunting locomotive. The locomotive was powered by a 204 horsepower Gardner 8-cylinder diesel engine. This was a good move as the same unit was used in both the Class 03 and Class 04 shunters. The thing that makes it a little unusual is that the engine was not driving a generator for powering electric motors. The 05s, in common with a few of the modernisation plan shunters, were diesel-mechanical. This means that they have a clutch and a 4 speed gearbox that are connected directly to the wheels, just like a car. The final drive to the wheels goes via a reverser gearbox (as the locomotive needs to go just as well backwards as forwards) to a jackshaft under the cab which was connected to the driving wheels by coupling rods, in a seeming tribute to their steam forebears.

John Crane repainting DL26 in August 2016

There was a grand total of 69 of them built. Production ran between 1955 and 1961. They look very similar to the Class 03 and 04 shunter designs. They were not particularly heavy and weigh just 31 tons. They were never going to win any performance competitions. They had a top speed of just 18mph and a maximum power output of 14,500lbs tractive effort. They were used primarily on the Eastern and Scottish Regions of British Railways.

Commercial users were quick to see the usefulness of the class and Hunslet built four more for industrial use in 1958. These were not exactly the same as the Class 05s as they had a tall bonnet and different window arrangements. This was to accommodate a different power plant, a stronger 264 horsepower National Gas diesel engine. Two of them, Nos DL25 and DL26, were bought to work in the National Coal Board (NCB) East Midlands area at Pleasley Pit.

In December 2018 a cake was baked to celebrate 40 years since DL26 had arrived at Didcot Railway Centre

The second not so clever move by the British Railways modernisation project was that there was no cross-communication between those doing the modernising and those doing the reshaping. The brutal truth was that the cuts made after the infamous Beeching Report, meant that the railways would lose huge amounts of track, jobs and purpose – and with the purpose went many jobs for locomotives as well. The switch to bulk freight meant that the need for the hundreds of shunting locomotives ordered was in steep decline. Couple this with British Rail's policy to moving towards standardisation of classes, a relatively small class of 69 machines didn't stand a chance in this new world order.

The Class 05s were almost all withdrawn between 1966–1968. The sole survivor in BR service was No. D2554. This locomotive had been allocated to the Isle of Wight for shunting duties on the small railway there. In this form, she lasted in service until 1985. She's still there too as part of the Isle of Wight Steam Railway fleet. Her lack of an air brake system means she can't be used on passenger trains but she's still shunting! Another locomotive still shunting is No DL26. She was withdrawn by the NCB in 1978 and was acquired by the Great Western Society as the museum shunter. Her role was somewhat reduced when Class 08 No. 08 604 Phantom turned up. The 08 has the advantage of being a bit more powerful.

However, there is still a role for No DL26. The design was intended to be light and this means that The Rat, as she became known to volunteers, is the locomotive used to go across the traverser in the carriage works. No DL26 doesn't have either a vacuum or an air brake and can't be used on passenger trains but just like her cousin on that southern Isle, she continues to be a really useful shunter.

Remarkably for a design that had little impact on history, four of the original Class 05s have survived as well as a few of the industrial versions. They were being taken out of service just as the burgeoning preservation movement was getting going which, despite their seeming run of bad luck from the get-go, was at least a cloud with a silver lining for a few.

FRIDAY 4 NOVEMBER

The Big Bang?

In a further tenuous attempt to theme my blogs, let's go out with a bang this week. Given that we’ve not long had Diwali (the Hindu Festival of Lights) and Britain's very own November 5th celebrations ([not] blowing stuff up and burning a chap at the stake), this time of year is always a bit ‘explosive heavy’. But how did those explosives get from one place to another on the Great Western? How did they do it safely? Well…

There is one thing you really DON’T want when dealing with explosives and that is sparks. If you make a spark in the right place, at the right time, you will be seeing a very bright light indeed for the rest of your life. Just don’t expect longevity. Therefore, any vehicle that carries explosives of any kind has to be as far as is reasonably practicable*, geared to preventing them. This problem was made potentially worse during a good part of the steam age by the use of hob nail boots. A steel boot nail struck against the steel of a wagon can result in a healthy spark.

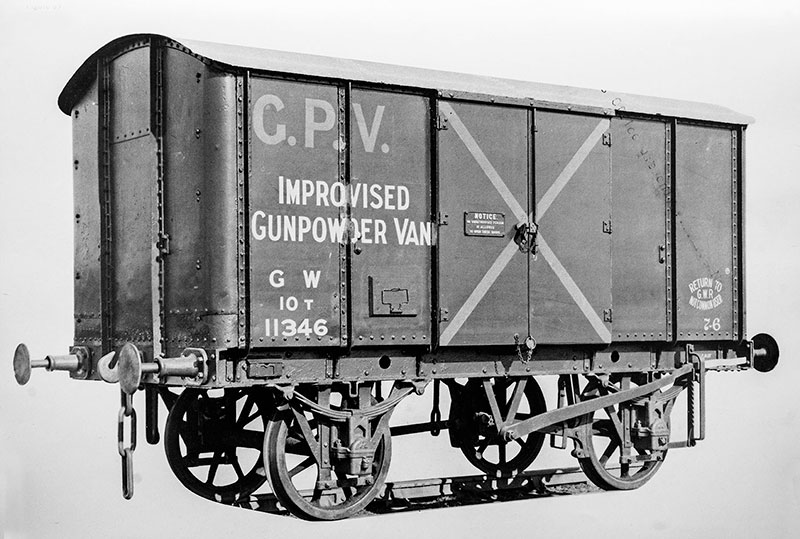

Van No 11346 was converted from an earlier iron vehicle to a gunpowder van. Note that the ventilator in the centre of the end wall, just below the roof, has been blocked up. The fact that it has been converted gives it the description ‘Improvised Gunpowder Van’. Photograph published in ‘Freight Wagons and Loads’ by Jim Russell

The big way of mitigating sparks is in good choices of materials. What you don’t want is ferrous materials exposed to areas where you don’t want sparks. Ferrous materials are those that contain iron. The word is derived from the Latin for iron, Ferrum. It’s also why the chemical symbol for iron is Fe. As a result, despite being steel bodied vehicles every attempt was made to keep moving bits of steel apart. The first thing they did to the vans was to line them with timber boards. These were fastened to the wagon with brass screws.

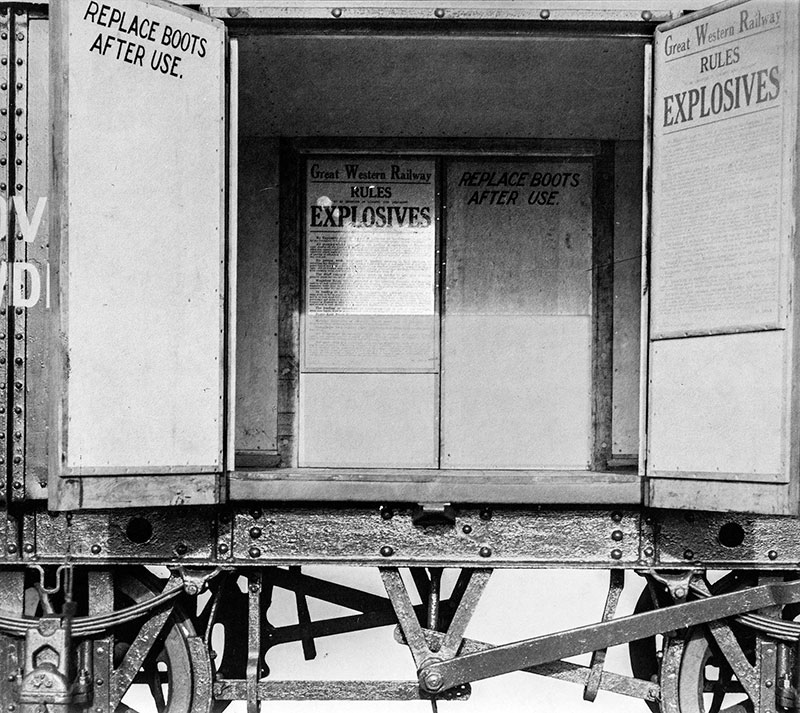

Further to the boards, the majority of the sides were lined with lead sheeting too. Also non-ferrous. As were the copper nails that fixed it to the boards. The door bolts, hinges and other gear was all made of brass so the were no sparks there either. The metal was also coated with a white lead oil paint where it came into contact with the wood. The other difference between these and regular freight vans is that they had no ventilation. In fact they had to be dust proof. Think about it – what you really don’t want is to have a breakage of a bag of loose explosive powder, have it whipped up by the air rushing through the ventilation carrying that powder outside and somewhere near a steam engine. It would become exciting. Briefly.

The interior of van No 11346 was lined with wood to prevent sparks. Photograph published in ‘Freight Wagons and Loads’ by Jim Russell

There were also strict rules about operating these vehicles. Firstly, these wagons were always loaded and unloaded outside a goods shed, never inside. The reasons for this being what would happen to a building and its occupants if something went horribly wrong. Each van was also provided with a pair of what was known as ‘magazine boots’. These hung on hooks inside the doors. They were a kind of overshoe that was worn as a last line of defence to keep those hobnails away from striking other iron. There was a long list of rules on a poster on the door opposite the magazine boots. This outlined safe practices. Another key point from this list was that these vans were only to be unloaded and loaded between sunrise and sunset. The reason being that many mobile light sources at the time involved flames…

The vehicles were not allowed, full or empty, to travel through the Severn Tunnel. Again, a healthy explosion down there might have quite literally brought the house (river) down. The loading of these vans was limited too. The vans could carry no more than 10,000lbs each and, no more than 5 of them could be coupled together in a train. They had to be placed as far as was practical from the engine (for obvious reasons!) and also as far away as possible from any wagons marked up as having ‘inflammable’ contents.

A pair of leather overboots to wear in gunpowder vans, with the GWR roundel embossed in the soles. These boots are in the Great Western Trust collection at Didcot

This was fine during peacetime but during the world wars, these regulations were relaxed somewhat. The maximum load for a van was 16,000lbs and trains of up to SIXTY of them were not unheard of. Had one of those gone up, it would have left quite the crater.

They became known in general railway parlance as Gunpowder Vans but this was more usually shortened to G.P.V. This was usually emblazoned on the side of the vehicle in large red letters. The G.W.R. had their own unique telegraph code name for them – CONEs. These vans were all designed under the wagon index letter of Z. The first CONE wagons were built way back in 1874 and were partly new build and partly conversions of older stock.

The design eventually began to look a lot like the IRON MINK**, but without the ventilators and all the other precautions added. In fact conversions from CONE to IRON MINK or the reverse are quite common and make the history of these vehicles quite complex. Their numbers ebbed and flowed with the tides of war as well, adding another dimension to the tale. GWR liveries were a special overall black. In addition to the traditional white numbering and ownership markings, they received red G.P.V. marking as well as large red ‘X’ on the doors.

Our wagon is No 105781. It was built in 1939 to diagram Z4 as part of Swindon Lot 1346. There were 25 of this type built. The Z4s are 16’ over their headstocks, their bodies being extended to suit a new chassis. This chassis was exactly the same as the P18 ballast wagons that were used by the Permanent Way Department for maintaining the track. This wagon was preserved as part of a small batch by the late David Rawlinson, who took them to Southport, then to Preston Dock. After he passed away, they were bequeathed to the GWS and came to Didcot via Crewe in 2007.

Gunpowder Van No 105781 preserved at Didcot Railway Centre, and recently repainted

The underframe is in pretty good condition as is the associated running gear. The issue is with the upper body which is in quite poor condition. It’s going to need a fairly extensive restoration but for now, our expert wagon dabbler, Ann, has given it a protective coat of paint to arrest the rot and to make it look the business while it is stored alongside the loco works, awaiting its chance. A bit of period correct lettering and it looks quite smart from the train on the main demonstration line. This is yet another example of the wonderful world of common carrier wagons, when the railways took any cargo it was asked to and quite often had specialised rolling stock to do so.

*If you've written risk assessments, you'll know what I mean!

**No, that's not some kind of G.W.R. heavy metal band…

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.