Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - October 2022 - Going Loco - October 2022

Going Loco - October 2022

FRIDAY 28 OCTOBER

The Universal Saddle Bag? Part 6: Mutant Monster Panniermania!

Velcome to ze blog! Mwahahahah! and other 1950s monster movie stereotypes… I don't really do Halloween well do I? Oh well, I tried! Mind you, there are always a few horrors hanging about in GWR locomotive history. But these are not necessarily horrors, more mutants. They had their uses, they were just odd! Far less like Dracula and more like the X Men I suppose. Just like their comic book equivalents, each has its own super power…

Tiny Mutant

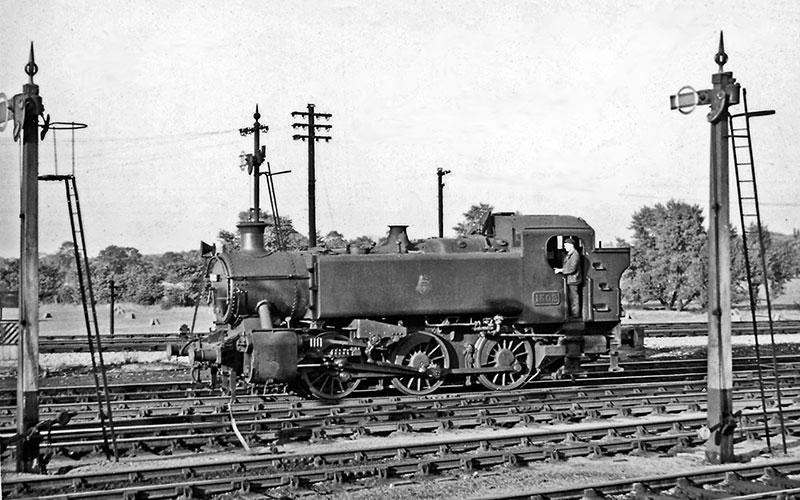

Photograph from A Pictorial Record of Great Western Engines by Jim Russell

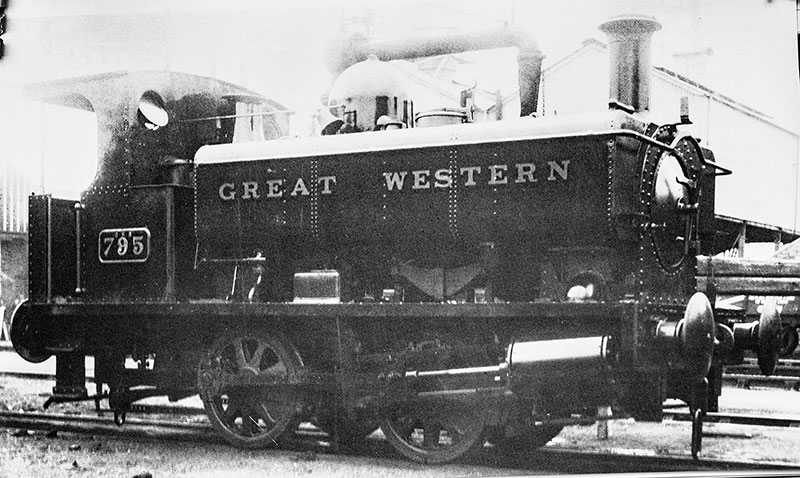

Able to fit in the tiniest of spaces, it's the pocket pannier, No 795. There was a railway oddity that was absorbed into the GWR at the Grouping in 1923. Powlesland & Mason were not a railway in a traditional sense. They provided locomotives for use on the Swansea Harbour Trust’s network. As of Grouping they contributed nine 0-4-0 saddle tanks to the GWR fleet. Two of them had the unusual distinction of being some of the last steam engines built by the Brush Electrical Engineering Company. This happened through a succession of corporate takeovers and these were some of the last on their books.

The two 0-4-0s in question were built in 1903 and 1906 and were given numbers left over from other withdrawn engines to get them on the Western's books. They became Nos 921 and 795. In 1926, Swindon put No 795 through a heavy rebuild and this resulted in a new boiler and the fitting of pannier tanks in the place of the saddle tank. This made her the only 0-4-0 pannier the railway ever owned, and the smallest. Despite this they were both withdrawn from the GWR in 1928/1929. They both survived in industrial service until the 1960s but sadly No 795 was scrapped. No 921 is still with us though, so a reminder of this tiny pannier still exists.

The Original Mutant

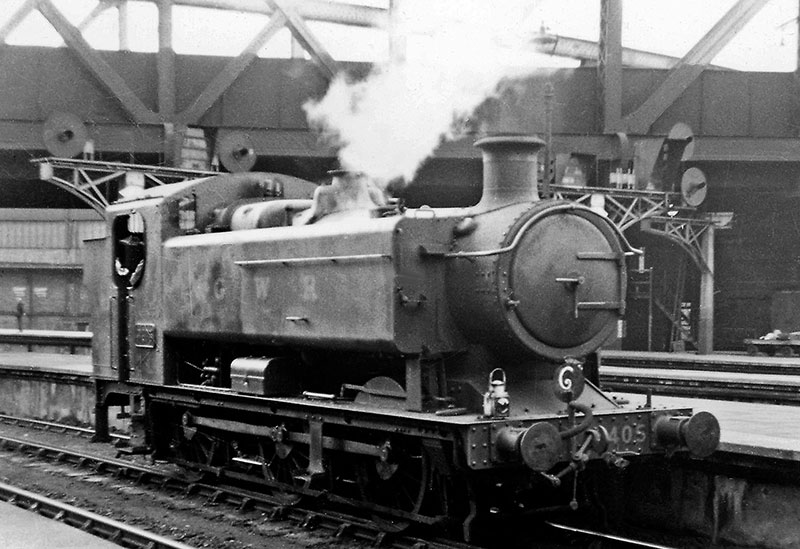

Photograph from A Pictorial Record of Great Western Engines by Jim Russell

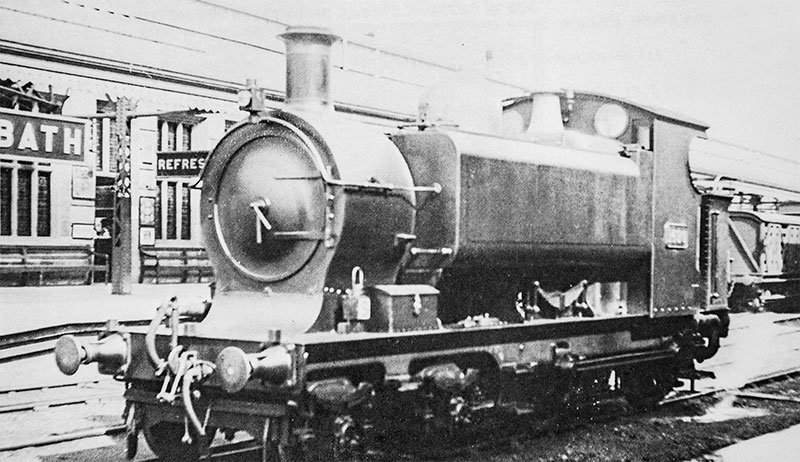

The first ever GWR pannier tank was far from the picture you have in your head when I said pannier tank. Firstly she wasn't an 0-6-0. Secondly she was intended as a replacement not for shunting engines but for the Metro 2-4-0 tank engines (a kind of early 14XX sort of a thing). Thirdly instead of being built in any sort of numbers, she remained unique and finally, unlike the majority of GWR pannier designs, she was useless…

Photograph from A Pictorial Record of Great Western Engines by Jim Russell

This 4-4-0 pannier tank was built in 1898 and gained the number 1490. The thing about the 4-4-0 wheel arrangement is that it is very easy to get wrong. The ride can be terrible, the swaying of the front end under load enough to make the crew seasick and the whole thing can become a nightmare. No 3440 City of Truro did quite well as a 4-4-0 and the Southern Railway Schools class had a great reputation. Guess where No 1490 fell? Not on the City of Truro side of things… Piled on top of the rough riding was a whole heap of engine. She was just too heavy as well!

Far from the duties of the Metros, she ended up shunting at Swindon and Bath and was sold into industry by the early 20th century. She ended her days in colliery service, being finally broken up for scrap in 1929.

Warrior Mutants:

0-6-0 Dean Goods Pannier Tank Tender Engines with condensing gear and an air brake pump fitted too! Yep, you read that right, a tender tank engine! A number of the venerable Dean Goods class were called up into service in the Second World War. Some had been veterans of the First too. Ten of the veteran locomotives were so fitted. We have talked Dean Goods before* but we are fortunate that No 2516 is still with us at Steam Museum in Swindon as part of the National Collection.

Caterpillar Mutant

Photograph by Lens of Sutton, printed The Locomotives of the Great Western Railway, Part Ten, published by the RCTS

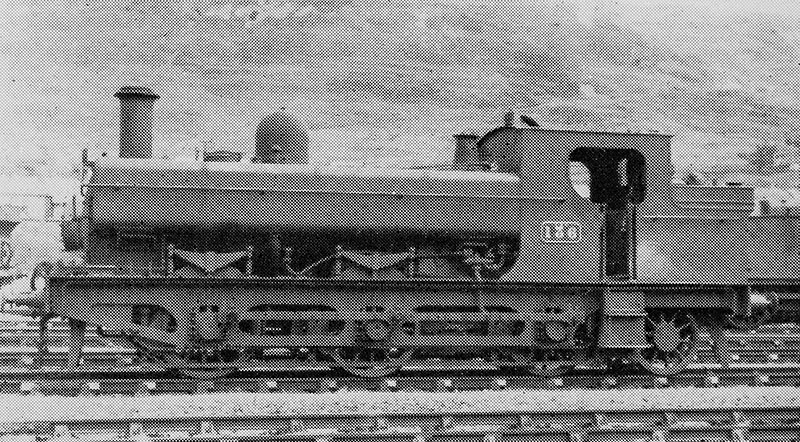

This is the opposite to the tiny pannier in many ways! She didn't have any more wheels than No 1490, just in a different order… No 139 was originally built as a ‘K’ class 0-6-2 saddle tank for the Rhymney Railway. Like many of the absorbed locomotives – usually 0-6-2s – she was adapted to use some of the GWR's technology. These Swindonised engines were quite common. In fact, our very own Nos 1338 and 1340 Trojan are less radically rebuilt examples of this. No 139 was simply unusual in that she was an 0-6-2 and therefore had two more wheels than the average pannier after conversion. She certainly didn't have the most wheels a pannier ever had though…

Super Strong Mutants

Able to lift tons of weight, they are the mighty lifting monsters – the crane tanks. These were nothing new, the idea of mounting a crane on board a locomotive to combine shunting and lifting was relatively commonplace. They were based on the 850 class saddle tanks that were designed by George Armstrong and were built between 1874 and 1895 at the GWR's Wolverhampton Works. Several were rebuilt to become pannier tanks and they were only completely replaced from service from about 1949 onwards by Hawksworth's 16XX pannier tanks.

In 1901, Swindon took the drawings of the 850 class as panniers and adapted them to become crane tanks. The frames of the engines were essentially extended rearward to create a large platform with a 4-wheel bogie underneath. On top of this was placed a crane. This was steam powered, the steam coming from the locomotive's own boiler. When not in use, the crane jib was slung over the cab roof and along the boiler. They became No 17 Cyclops and No 18 Steropes. A third, No 16 Hercules was built in 1921. They rarely left the workshops at Swindon or Stafford Road, so were not a common sight elsewhere. They were all scrapped in 1936.

The evolutionary process that the GWR locomotive fleet went through meant that there were both winners and losers. It truly was a case of survival of the fittest. There were several reasons why these engines remained in very small numbers. Either they were an adaptation that was for a very specific niche that didn’t allow for any further duplication, or an attempt to extend the lifespan of an existing machine. Oh, and one or two were just no good! Whatever the reason, history has left us these fascinating dead ends to marvel at and to consider what might have been had things been just a little different…

*They Also Served, August 2021. Scroll down here:

Going Loco - August-2021

FRIDAY 21 OCTOBER

The Universal Saddle Bag? Part 5: The Oddball

In our continuing look at all things pannier tank for now it’s a bit like we’ve got to the bottom of the metaphorical barrel and found the strange and unusual lurking around at the bottom. There genuinely were some very strange versions of the pannier tank that came out of Swindon and as a bit of something different, let's take a look at one of them.

No 1501 during a Timeline Events photo charter at Didcot on 2 May 2015, while visiting from the Severn Valley Railway

The only one of these types that is represented in preservation is the last new GWR design that was built. They didn't see the light of day however until 1949. Well into the nationalised era of British Railways. If we claim that the design of the 94XX class was unusual (which we did last week!), then the 15XX class can only be described as outlandish!

The design was quite unlike anything that the GWR had ever produced. It was quite like something the Americans had produced. We have already had a look at the S100 0-6-0 tank engine*. To recap quickly for our purposes however, the S100 was designed by Col. Howard G Hill as a mass-produced switcher (the American term for a shunting engine) that could be used as part of the war effort in WWII. Some 382 of these powerful little machines were built and they saw service throughout the war and long into the post-war period. In fact a few are reportedly still at work even today!

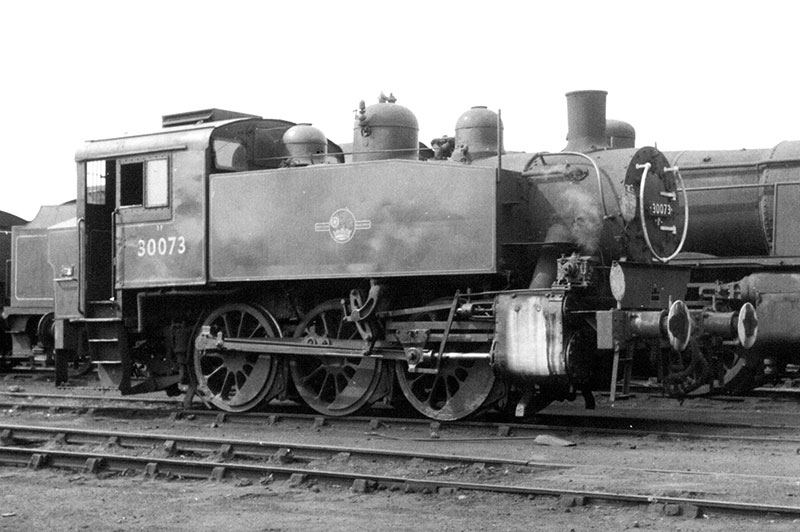

The USA S100 tanks have a similar arrangement to the GWR's 15XX – large outside cylinders, Walschaerts valve gear, short wheelbase, no running plate. Southern Region No 30073 was at Eastleigh in August 1966. Photograph by Gillett's Crossing

There can be no denying the similarities between Hill's design and Hawksworth's. The GWR had experience with using the S100 during the war and it isn’t a surprise that they felt the need to have a go themselves. The Southern Railway were so enamoured with them that they bought 14 original S100s – a few of which still survive in preservation. The 15XX class followed many of the design cues from the S100. It has a strikingly utilitarian, stripped down look. The first thing is that they do not have a traditional running plate (the flat area above the wheels usually there to allow crews to access the boiler). Therefore there were no wheel splashers (the ‘mudguards’ as I heard someone call them the other day!).

No 1502 shunting at Didcot with the Provender building in the background. Photograph by John Coiley

Apart from the bare sides, the other hugely obvious giveaway that this was something different was the hulking great lump of outside Walschaerts valve gear on each side. Very few other Great Western designs had this arrangement of outside valve gear, that became a kind of de facto standard on all other British railway companies and BR itself. Apart from a few oddballs, the only two other well-known GW examples being the 1101 class 0-4-0 dock tanks and the Steam Railmotors, like our very own No. 93. This was mainly to allow the easy oiling and maintenance of the valve gear, just like on her American cousins.

No 1502 at Didcot on 2 August 1957. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

The upper works were practically the same as the 94XX class of panniers that we discussed last time, the same Standard 10 boiler, wide cab and so on. The only other big difference between the 94XXs and the 15XXs was the wheelbase. The distance between first and last driving wheels was 15’ 6” on a 94XX but just 12’ 10” on a 15XX. This was intended to give them the ability to get into even the tightest curves. Which it did. If the track was up to it. If the 94XXs were restricted by their weight, the 15XXs were positively crippled by theirs. These engines weighed 58 tons 4 cwt. By comparison, a 57XX pannier for example weighed just 47½ tons. Red Route restrictions all the way…

No 1507 at Old Oak Common in 1962. Photograph by Mike Peart

Couple that weight with huge pistons swinging about fore and aft and the cylinders positioned to the outer edge of the frame, it meant that their tiny wheelbase caused them to pivot side to side quite alarmingly as their speed increased. While their immense strength was beyond doubt, they were prone to derailing if mishandled and driven fast. This limited their effectiveness in some of the traditional pannier roles, although, to be fair, the shunters they were based on were just that, shunters. So they were, just like Hawksworth’s 94XXs, something of the proverbial curate’s egg – good in parts. While the 94XXs totalled 210 engines and the S100 got to an impressive 382, the 15XXs weren't so lucky.

No 1504 leaving Old Oak Common yard with empty coaching stock to Paddington on 27 April 1963. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

By the time the first – No 1500 – was built, it was already 1949. The GWR was gone and there was a plethora of the more adaptable 94XXs either in service or on the order books. So much so that just ten were constructed numbered 1500 to 1509. The class were restricted in their usefulness and as a result, they really didn’t work widely. Six were allocated to Old Oak Common depot in London and spent the vast majority of their working lives pulling empty coaching stock into and out of Paddington station. No 1501 was a stalwart at Southall shed on shunting and short-haul goods workings. A similar career was had by No 1502 and this one has local interest to us in that she was based at Didcot. Nos 1506 to 1509 were allocated to the same duties but in Newport in Wales. And that was practically that. By 1964 the last of them was withdrawn from service.

Except that a number were sold for use by the National Coal Board and from there, No 1501 was eventually preserved by the Severn Valley Railway. They bought three of the NCB examples and then used the parts to make a fine example, fit for preservation. And fit for preservation she is. She has visited Didcot and enabled us to recall the memory of her long departed Didcot sister, No 1502. A fine tribute to an obscure class that has become a favourite engine in preservation. The design lacked a lot of things but possibly the thing that saved No 1501 is the fact that there is one thing that these machines possess. In spades. Character…

*They Also Served, August 2021. Scroll down here:

Going Loco - August-2021

FRIDAY 14 OCTOBER

The Universal Saddle Bag? Part 4: The Less than Universal Version…

We seem to nearly be at the end of the pannier story for now – although a return to take a look at our own No 3738 at some point would be good. There were two other pannier designs – neither represented in the collection at Didcot, but both have visited us in preservation. These have two things about them. One, they were the products of the last Chief Mechanical Engineer of the GWR, Frederick Hawksworth. Two, they are both weird outlying designs for various reasons so it’s worth us taking a look over the next couple of weeks.

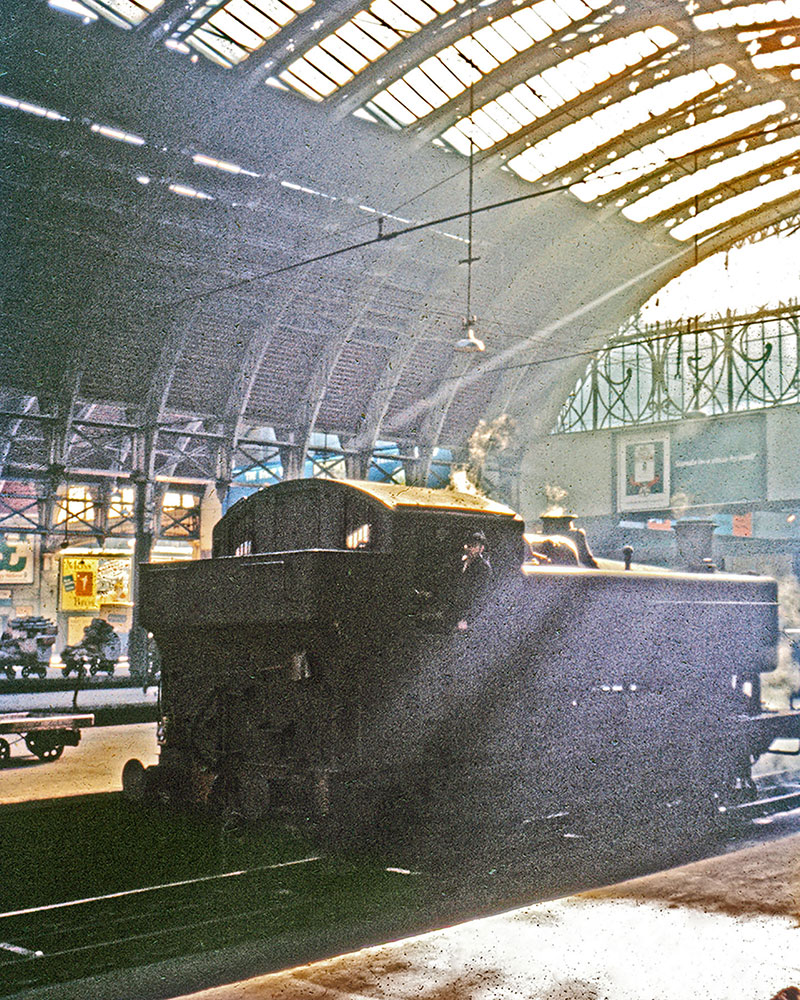

No 9405 on carriage pilot duty at Paddington station on 5 July 1947. The locomotive was just a month old, having been built at Swindon in May 1947. She was withdrawn in June 1965. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

The heaviest 0-6-0 pannier design was one of the last. The story goes that the running superintendent for the GWR wanted a few more of the 8750 class panniers for the railway and when the order was put under the nose of the then General Manager, Sir James Milne, he suggested that coaches at Paddington should be pulled in and out of the station by “something a little less Victorian looking.” In essence, Sir James was actually after something without the huge steam dome. Hawksworth had other ideas…

No 8432 at Swindon Works in February 1953, having been delivered new from the Bagnall Works at Stafford. She was withdrawn in July 1959. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

What he ended up with was kind of a cross breed between the 8750 pannier and the 2251 class 0-6-0 Collett Goods. The biggest visual change was the removal of the steam dome – a taper boiler gave it the look that Sir James was after. The smokebox extended beyond the tanks, unlike most of its earlier cousins. The cab was made spacious and wide. The cab sides stretched out to almost the full width of the engine. He also removed the coil suspension springs out of the cab and placed leaf springs under the cab instead. This had a few unfortunate effects. First was that when shunting, the driver couldn’t look out and reach all of his controls at the same time. Not great for a shunting engine. It made it very difficult to get up to the coal bunker too and various arrangements of steps were contrived to allow crews to do this. The leaf springs gave the crew more space but made the ride worse. This didn’t endear them to their crews.

Nos 8400 and 8401 at Bromsgrove engine shed on 18 August 1960. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

What didn’t endear the design to the traffic department was the fact that they were 9 tons heavier that the 8750 class. This was a problem. The previous design had an axle weight of 16 tons 15 cwt. The new design had an axle weight of 19 tons 5 cwt. Not much less than a Castle class express passenger engine! That means it was classified as a ‘Red Route’ engine. This restricted the new 94XX class to routes with structures capable of handling their not-inconsequential mass. This restricted them to about 50% of the GWR network. The 8750 / 57XX class were ‘Blue Route’ engines until 1950 (which was well over 60% of the network) and then ‘Yellow Route’ thereafter. This meant there was just 13% of the network that they couldn’t access. For a supposed shunting design like the 94XX, the lack of route availability was bad news.

Banking a heavy oil train on the Lickey incline on 16 August 1963, these are Nos 8402, 9430, 8400 and 8401. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

Hawksworth was conservative with his new design and ordered just ten from Swindon Works. Nos 9400 to 9409 were notable in two ways. They were the only 94XX machines with superheaters – a kind of turbocharger* type affair for a steam engine. The first ten were also the last engines built at Swindon whilst it was still a GWR owned property. These ten, completed in 1947, brought to a final close the complete independence of the Works as on 1 January 1948, the railways were nationalised.

No 3404 at Swindon Works in 1962. She was completed by Yorkshire Engine on 31 March 1956, and had an exceptionally short working life, being withdrawn on 13 July 1962. Photograph by Mike Peart

The GWR directors were not so conservative as Hawksworth and to the chagrin of many no doubt, ordered no less than 200 more of these engines! Swindon didn’t have the capacity for such building programmes and the work was farmed out to Robert Stephenson & Hawthorn Co. (100 units), W. G. Bagnall and Co. (50 units) and The Yorkshire Engine Company (50 units). These orders were placed in 1947 and the government was faced with either allowing the contracts to go ahead or potentially damaging the independent locomotive builders’ businesses by cancelling them. They choose the former. The build program was also drawn out – the last, No 3409, wasn’t delivered until 1956.

No 9425, at Swindon after repairs in 1962, was built in 1950 by Robert Stephenson & Hawthorns in Newcastle upon Tyne. This ’Geordie’ was soon on her way back to Barry (88C) with a freshly-painted smokebox and chimney at least. A North British type 2 diesel is lurking behind. The diesel may be more interesting than the pannier tank to some enthusiasts. Photograph by Mike Peart

Despite their limitations, they did find work all over as much of the network they were allowed to traverse. They were a common sight in their intended role at Paddington where they pulled the empty coaching stock in and out of the station. They also ran services similar to their predecessors taking and freight and passenger trains of all sorts as well as the shunting duties to which they were so ill suited.

A 94XX on carriage pilot duty at Paddington station in 1964 with the morning sun streaming through the roof

Being such late arrivals, their working lives were not long. The later examples were around for just half a decade or so. There are two survivors of the class. No 9400 is part of the National Collection and lives at the Steam Museum in her Swindon birthplace.** No 9466 was saved from scrap and was owned for many years by Dennis Howells MBE, who was the man behind the restoration of our King class locomotive No 6023 King Edward II. No 9466 now operates on the West Somerset Railway.

No 9477 with a goods train at Greenford in the early 1960s

So that leaves us with just one more class of Hawksworth panniers and they were a really strange type as far as the Great Western was concerned. There were a few other pannier oddballs in GWR history too. Perhaps a tour of the ‘ugly ducklings’ might be in order next week?

No 9466 during a Timeline Events photo charter at Didcot on 30 April 2016

*It’s really not like a turbocharger as it works in a very different way but it gives the same effect – a big boost in performance!

**I’ve always thought this was an odd choice as she was the only GWR pannier scheduled for official preservation. She’s hardly a typical example of the breed…

No 9466 arriving at Drayton Green station on 20 October 2018, with the Dennis Howells Memorial Train to Princes Risborough

FRIDAY 7 OCTOBER

The Universal Saddle Bag? Part 3: The Blue Pannier

I was fortunate enough to get a week off this week as I spoke nicely to Drawings Kev about his favourite locomotive and he was more than happy to tell us all about it. Without further ado, take it away Kev!

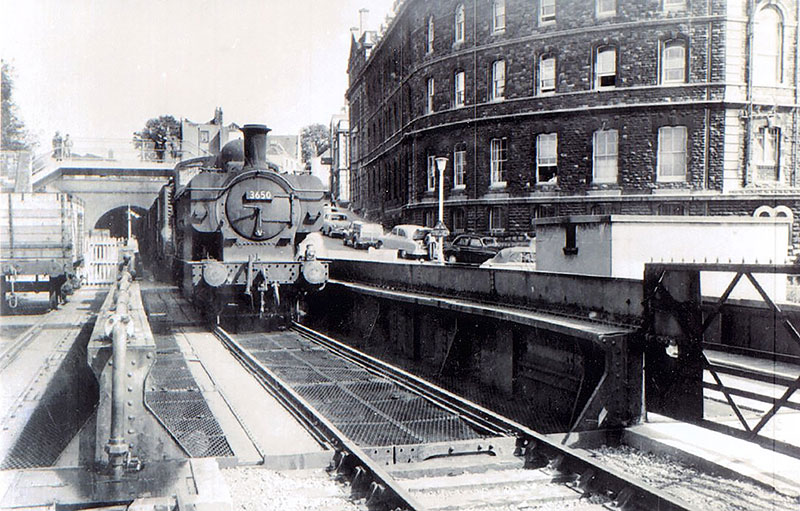

No 3650 is one of the 8750 sub class successors from the 5700 class pannier tanks and was built in December 1939 at Swindon as part of lot No 325 (Nos 3635-3684) at a cost of £2,844. She was finished in plain green livery with tank-side GWR roundels.

At Tyseley in 1947

The main difference between the 5700 ‘flat cab’ version and its 8750 successor is a bigger cab and windows, and both injector water valves moved to the fireman's side, rather than one each side, making it awkward to get to the driver’s side water valve. The Pannier Tank lineage from the days of Armstrong and Dean have been well covered by Drew, so I’ll stick to my involvement with No 3650 for now.

No 3650's first allocation was to Tyseley in January 1940 and was there until October 1953. Subsequent allocations include Bristol Bath Road, Radyr, Cardiff East Dock, Abercynon, Bristol St Phillips Marsh and lastly to Neath on 5 October 1961. No 3650 was condemned by BR on 24 September 1963, with 493,103 recorded miles. Then after having the steam heat and vacuum brake systems removed, was sold to Stephenson Clark (PD Fuels Ltd) and shunted spoil trains in the Gwaun-Cae-Gurwen colliery area of Wales.

At Filton on 6 September 1958. Photograph by Mr Frith

I guess locos sold to private concerns at this time were considered ‘throw away’ items so 3650 continued to work until lack of maintenance and washouts caused broken stays and firebox bulges where scale had built up some 12 inches deep. The tyres became worn hollow so they appeared to have flanges on the outside, and the front tube plate became so thin it also caused concerns. A photo we have taken on 7 April 1969 shows No 3650 lifeless at Gwaun-Cae-Gurwen with smokebox and cabside number plates finally removed.

On the Bristol Harbour Branch crossing the Bathurst Basin lifting bridge, c.1960. Photograph by the Bristol Evening Post

No 3650 was bought by a GWS member on 31 October 1969 and was moved to Hereford then on to Didcot in 1970. Didcot’s other pannier, No 3738, came from Barry scrapyard in 1974 and although much of the non-ferrous pipework and fittings were missing, was in better condition than No 3650. Utilising some of the pipework from the substantially complete No 3650, No 3738 was returned to steam within a couple of years, leaving 3650 as a long term project needing much more attention.

At Gwaun-Cae-Gurwen on 21 April 1966, in steam and still carrying cabside and smokebox numberplates. Photograph by R Monk

In stepped No 3650’s new and current owner Brian Thompson in 1984.

Over the next three years, various volunteers pitched in and removed the tanks by July 1984, the boiler by August 1986 and the wheels by August 1987. Architect Brian, having designed the new works at Didcot, had the first engine, No 3650, moved in to the corner on No 1 road and over the winter of 1987 a restoration team started to form. To say the work needed was substantial and comprehensive would be an understatement and would fill a quite boring book. So we will fast-forward 21 years to 2008…

The restoration team in March 1989

Some 4,000 restoration photos later, riveting, welding, turning, milling, bushing, pinning, white metalling and hard heavy graft, including blackened fingernails, cuts, bruises and many choice words not in the dictionary, No 3650 returned to steam for the first time. While running in, No 3650 was painted in the Stephenson Clarke blue livery in which she last worked. This caused interest within the enthusiast and photo charter areas and even prompted Bachmann to produce a limited run of 504 ‘OO’ gauge models. Brian and I were presented with Nos 1 & 2 of the production run and I had to sign all the 504 certificates!

Running in, carrying blue Stephenson Clarke livery, on 9 August 2008, with Geoff Hinks as fireman. Photograph by Kevin Dare

Over the winter of 2008/2009, No 3650 was painted in plain green with the GWR roundel (gold leaf don’t ya know) on the tank sides and TYS on the front corner of the running plate. As is the way of things, a photo from 1947 later surfaced but in the non-conforming Tyseley style, having the TYS on the sand box,… So out came the white paint again! During the 21-year overhaul, No 3650 has had around a dozen core volunteers with others coming and going as their time allowed. We have our own memorial bench with five names that never saw No 3650 steam and a further two since the overhaul was completed.

Crossing Victoria Bridge on the Severn Valley Railway on 12 August 2012. Photograph by Matt Baker

No 3650's busiest year saw over 90 steamings at Didcot alone, ranging from normal open days, photo charters, railway experience and schools days plus the odd filming. In 2011, she spent the summer season at the Swindon & Cricklade Railway and in 2012 the summer at the Severn Valley Railway when they had a temporary loco shortage, and the winter/Christmas at the Bluebell Railway for the same reason.

Panniers are great locos to drive and can do most things that are needed in preservation, see this video for a footplate experience on 3650: . Panniers thrive on shunting as you would expect, especially with a pole reverser and would probably top out at 60mph if pushed, which made them so useful working passenger trains as well.

They carry up to 3tons 6cwt of coal and 1,200 gallons of water and weigh 49tons 0cwt, which allows them to go pretty much anywhere. They were even downgraded from Blue to Yellow route availability in 1950 due to their axle loading and low hammer blow.

On the Bluebell Railway, 18 November 2012, working up the 1 in 75 with Kevin Dare driving. Photograph by Dave Warwick

At Didcot, with economic driving, 1,200 gallons will just about last the day, but it’s better to take water at lunchtime as a demonstration, rather than be getting too low at the end of the afternoon. As a further example, No 3650 could happily work a train of six coaches the 16 mile length of the Severn Valley Railway then require a water stop. But in contrast, working six coaches over the 9 miles of 1 in 75 at the Bluebell Railway also required a water stop afterwards. Just goes to show the difference when working hard.

So, No 3650 had her final steaming on Sunday 13 November 2016. Why a year early? Well, Didcot is a banana shaped curved site, the branch line being particularly so and we found the tyres were wearing and producing ‘toe radius build up’ or in simple terms, the flanges were getting too sharp,… Knife edges, if you like. The branch curve has now been re-laid with the check rail corrected and shouldn't present future problems, but for No 3650 at the time, better safe than sorry.

3650 starred during filming of Trainspotting Live on 12 July 2016, with presenters Peter Snow and Hannah Fry. Photograph by Tony Peters

The intervening years (Covid permitting) have seen No 3650 again stripped down and various non-destructive tests carried out on the boiler to produce a scope of works. The wheelsets are about to go away to the South Devon Railway for a re-tyre, as she already owns a new set of tyres. The original 1939 pannier tanks that have seen better days will also go with them and a new set will return. I’m thirty-something years older now than when I started back in 1987, but luckily we have some younger members of the group as well as a few of the old hands, so things are progressing.

Brian Thompson driving No 3650 to disposal on the final day of steaming during her first ten-year boiler ticket, 13 November 2016. Photograph by Catherine Fry

There's still plenty to do though and it'll be a few more years before No 3650 steams again, but we'll get there, even if they do have to hoist me aboard with a winch! In the longer term, Brian will be signing No 3650 over to the Great Western Society to ensure she always stays at Didcot.

Thanks Kev! It's another one of those underdog stories isn't it? No 3650 was battered, bruised and scarred but never quite dead… This engine and its crew have the attitude of many in the preservation movement and have basically said: ‘No, we aren't letting this go! There's life in the old dog yet!’ It takes quite a bit of faith from people like Brian and Kevin to believe in something that was as far gone as No 3650 was. But then again, isn't that what preservation of these magnificent old beasts is all about? Faith in the machine, friends to help you out, a store full of tools and near constant supply of tea. A recipe for success in my book!

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.