Home » Other Articles » Tuesday Treasures Index » Tuesday Treasures - February 2023 - Tuesday Treasures - February 2023

Tuesday Treasures - February 2023

TUESDAY 28 FEBRUARY

Inter-City

For many of the travelling public the term Inter-City recalls memories of British Rail’s long distance passenger services of the 1970s and 80s. In fact, the brand was launched on 18 April 1966 when electric services were introduced from London (Euston) to Liverpool and Manchester. The following March, Birmingham and Stoke-on-Trent services were electrified and the brand was heavily promoted by a television advertising campaign and photo shoots of the ‘Inter-City Girls’ including this, taken on 6 May 1968.

March 1967 also saw the end of through passenger trains between Paddington and Birkenhead and this event was marked by the Birkenhead Flyer and Zulu railtours, hauled respectively by 4079 Pendennis Castle and 7029 Clun Castle, both of which happily survive to this day.

In 1982, sector management was introduced by British Railways and Inter-City became the company name for fast city to city services. The hyphen was dropped in March 1985 and new branding, including the famous swallow motif, was launched on InterCity’s 21st birthday in May 1987.

InterCity was a great success and in 1989 returned a profit of £57 million on a turnover of £840 million. It remained profitable for the six years to 1994 when it was broken up on privatisation and the new railway organisation required ever higher government subsidies.

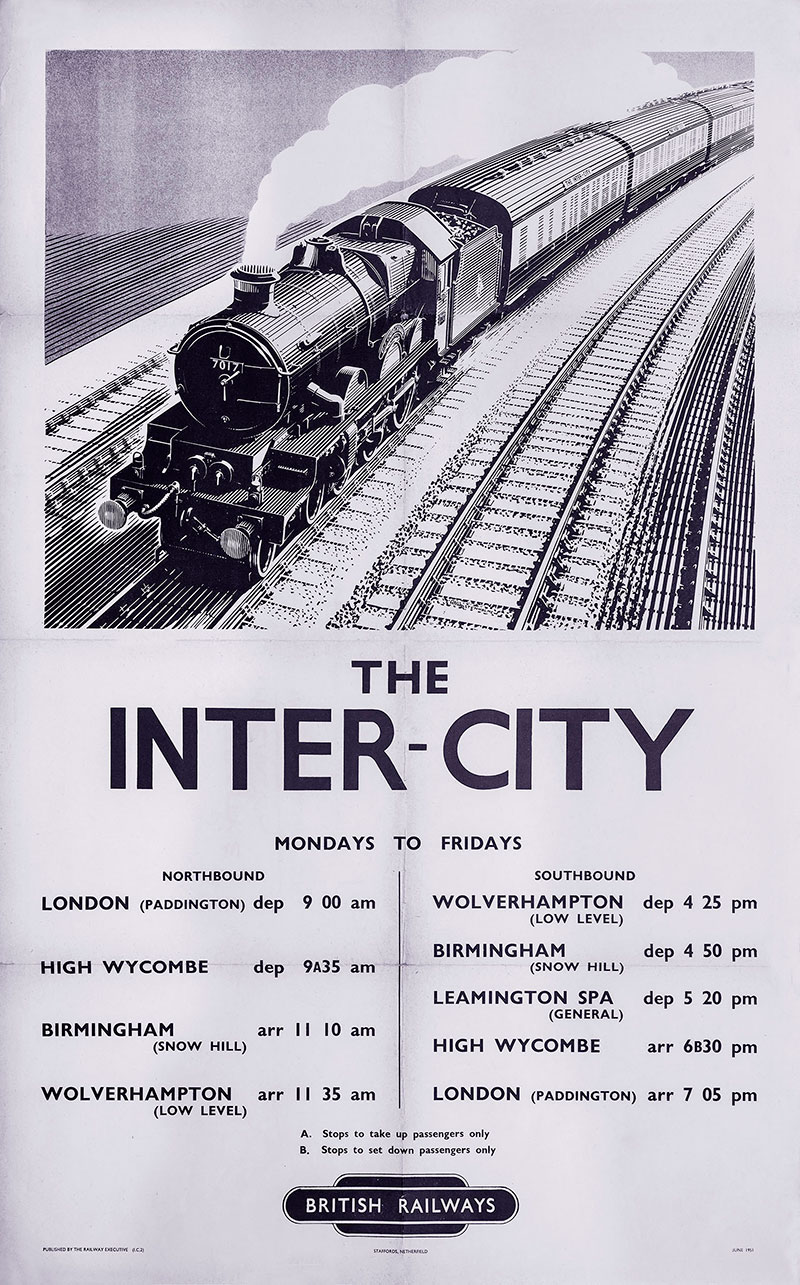

All of which leads us to 25 September 1950 when British Railways (Western Region) introduced a new 9.00 am service from Paddington to Birmingham (Snow Hill). This was christened The Inter-City thus pre-empting the later BR brand by some sixteen years. The service was provided to supplement the already heavily loaded 9.10 am service to Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Birkenhead and made only one stop to pick up at High Wycombe on its two hour schedule to Birmingham.

This poster from the Great Western Trust collection dates from June 1951 when the schedule had been eased to 130 minutes. It is by A N Wolstenholme, well known for his use of a scraperboard which gives such a vivid impression of speed.

As well as the ‘Castle’ heading the train on the poster we show a photograph (also from the GWT collection) of No. 6007 King William III accelerating the ten coaches of The Inter-City away from High Wycombe at around 9.35 am on 14 May 1959. The train lost its name in June 1965 in readiness for its adoption as the national marketing brand.

TUESDAY 21 FEBRUARY

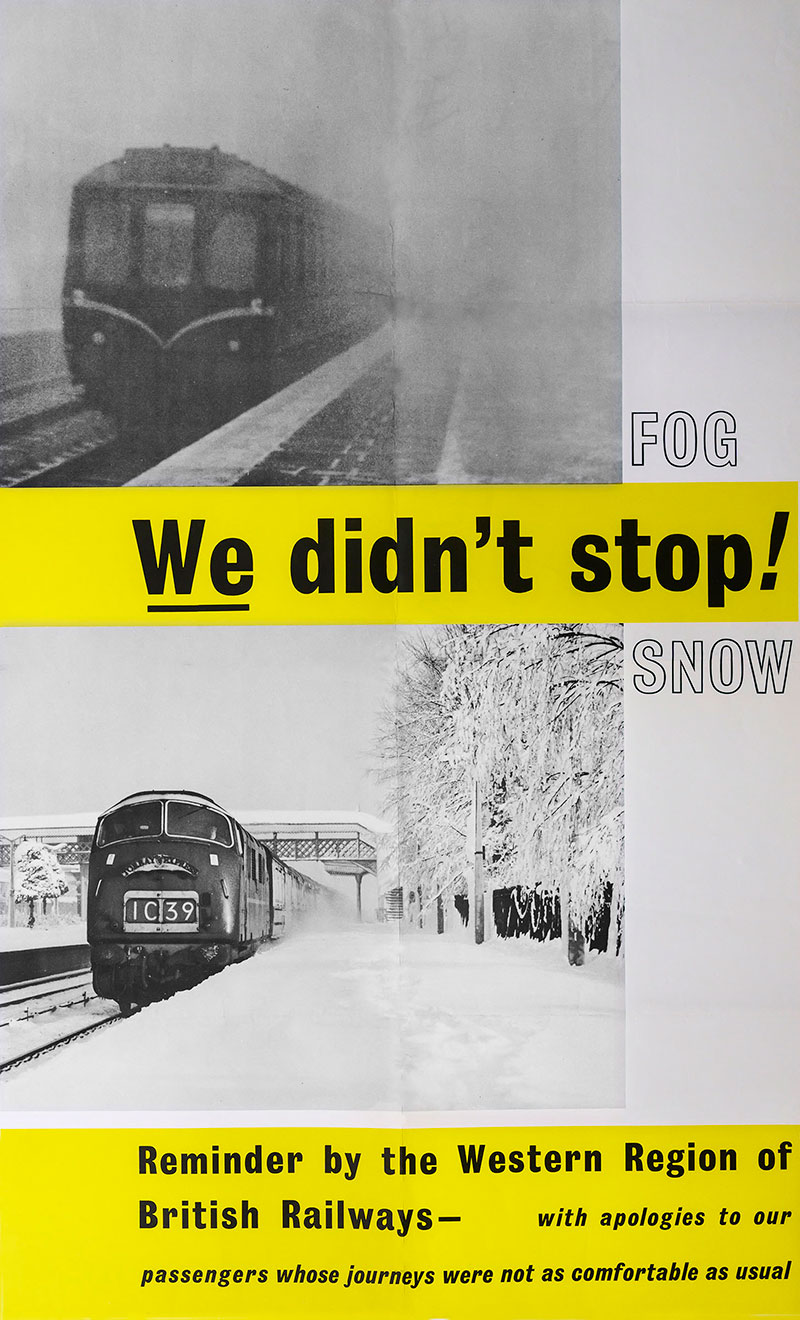

60 years ago, the arctic weather conditions in January and February 1963 were the worst on record for more than a century. Exceptionally severe frosts, with blizzards and very severe snowfalls continued from December of 1962 till almost the end of February. Some sea harbours and rivers became frozen up. Road conditions became chaotic. Some air services were cancelled and rail services were reduced. Most outside sporting fixtures were abandoned.

This poster in the Great Western Trust collection was issued at the time to illustrate how the railways had coped better with the extreme conditions than some other modes of transport. The article below, from the February 1963 edition of Western Region Magazine, describes the heroic efforts to keep the trains running.

WE SHALL NEVER FORGET IT

The year of 1963 has already made certain that it will not be forgotten – it has ushered in the bitterest weather spell of the century so far. The winter of 1947 was a landmark in Arctic conditions, but there was one saving grace on that occasion – there was a let-up during daylight hours. This time there has been none. The freeze-up has persisted all the time, and the depth of cold has been such that locos have frozen while running during the day! That is something this region has never experienced before. But we are proud to record that the men and women of the Western have won through this great ordeal, and it is gratifying to record the words of Mr James Griffiths, MP for Llanelly, in the House of Commons on 24 January: “In weather of the most severe kind, Wales has had to depend upon her railways, and all those connected with the railways deserve the public’s sincerest congratulations for the way they were keeping the services going.”

The toughest weather story of the century

There was hardly time to breathe the usual sigh of relief on Boxing Day before the snow came down, 24 hours late for the children and all too soon for the grown-ups.

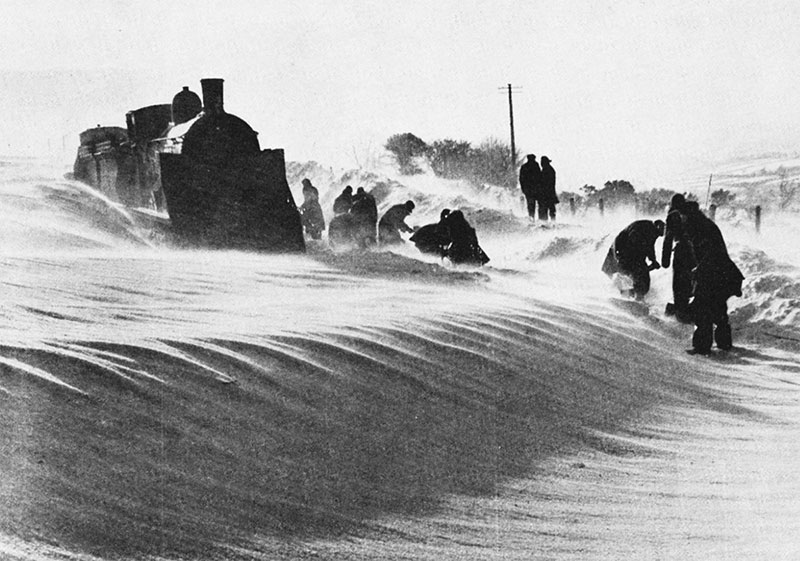

Devon turned into the wastes of Siberia. Railmen fighting to free a snow plough and relief engine trapped in the drifts which blocked the Okehampton to Tavistock line at Sourton. Photograph published in the Western Region Magazine

By the following morning drivers and guards, signalmen and gangers, porters and booking clerks were having difficulty in getting to their depots and stations. If a few trains were delayed – and Western Region was just finishing off the running of 109 extras over the holidays – there were few complaints. There was snow about, after all. Everybody could see that. And it had happened before.

What else was to come?

The night after that more snow fell. London and Bristol took the worst of it on this region. Five westbound and twelve eastbound expresses had to be cancelled, and the London division operated a restricted service. Next morning snow was still falling down in the west country, restricted services were still the order of the day at Paddington and, because the experts gave no hope of a break, railwaymen everywhere were on the verge of wondering what was coming now.

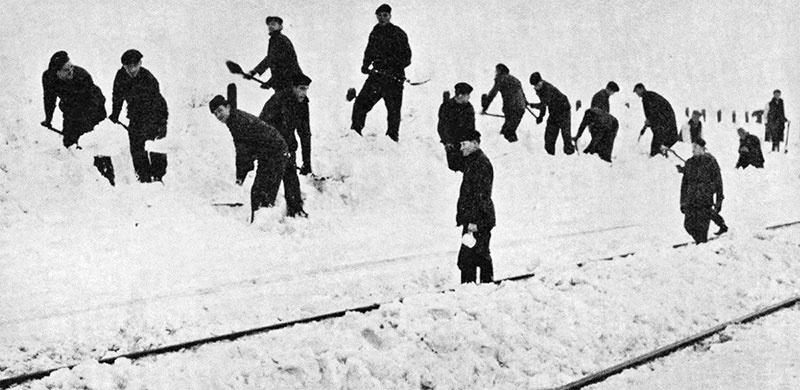

One of the hardest hit areas was the Oxfordshire plateau, and the drifts two miles from Haddenham station, on the border, had to be seen to be believed. Troops from Bicester were called in to help railwaymen fight a way through. Photograph published in the Western Region Magazine

They found out soon enough. More snow, up to the rail-tops. And with the snow – fog, mainly in the Midlands. Then more snow. And still more snow. A six-foot drift blocked the line at Ashendon Junction early on the Sunday morning and the ploughs were ordered out to clear it. They got through the huge soft banks of white late that evening and the line was open again by half past nine. (While they ploughed, the northern route trains were diverted via Oxford.)

Meanwhile, overnight trains from several points of the Western Region compass were heavily delayed, and if the snow eased off elsewhere it turned to sleet in Swansea. Frozen points outside Paddington meant a late start to seven trains. A thousand things began to happen all at once.

Snow ploughs out all night

On the last day of the old year the 9.35 pm freight from Banbury to Southall walked slap into a drift about a mile north of Haddenham, on the London-Birmingham route, and was only rescued at 5.30 in the morning by the Southall snow plough after a refrigerated stay of more than three hours. The 8.25 pm Shrewsbury to Marylebone milk train was held up behind the freight, and that repercussed back along the line to make a number of cancellations.

During the severe weather, priority was given to trains carrying oil and coal for fuel, such as this one in Sonning cutting. Photograph published in the Western Region Magazine

Down in the Vale of Glamorgan other snow ploughs were out all night, too, and between Yate and Westerleigh, as well as between Evercreech and Midsomer Norton, there seemed to be a wall of white looming up into the sky. But the railwaymen were there, while the millions slept in warm beds, with nothing promised except tears and toil.

Then came the respite, like the end of a journey through a long cold tunnel, the lovely sound of snow melting into water, water running into drains: the two-day (too short) thaw, when everyone hoped that this heralded the end of just another bad spell.

Not a bit of it. More snow blotted those hopes right out. Ashendon Junction got it again, and again expresses went through Oxford instead. The main line between Castle Cary and Taunton was impassable, the snow ploughs thrust their sharp noses into the cold once more, and delays mounted up into a heavy overdraft of time lost.

And so the story went on. The snow fell, froze on the ground, laid off for a few hours, fell again and froze again on top of the first layer. As fast as the points were cleared – by hand, often ungloved, and on two feet, often lumps of ice – they were filled in again. And were cleared again.

If a guard, a driver, a signalman or a shunter reached his depot somewhere near right time for duty one day, there was no guarantee he could make it the next, though it was never for lack of trying. (There is even a story of a porter who walked five miles down a line to see if any drifts would stop a train getting through. At six on a deathly cold morning, too.)

If an engine, even a steam engine, wasn’t frozen one night, no one could predict – even with fires in the pits underneath – that it would be as lucky on the following night.

Keep the lines free, that was the first essential all the time, a wicked enough job in the first phase of soft snow, a near-impossible one in the later freeze-up stage which lasted for weeks and shook railwaymen of 40 and 45 years’ service into admitting that they had never known conditions like these.

But before you work on this keep-the-lines-free theory you have to know where the stoppages are, and this is where HQ Control comes in, that ordinary-looking railway office which has perhaps a dozen more telephones than usual. Control is the nerve centre of the region in snow, fog, black ice or blue skies. Smaller control points along the line report news of happenings locally – the freight wagon off the rails in Wales, the engine failure in Gloucestershire, the effects of other upsets in other regions which have still other effects on our own – anything and everything.

It is Control’s business to know about and study every cause of delay and minimise – or, at best, avoid altogether – the effects on following trains. Even in normal conditions they have to think fast and far ahead. In sub-normal conditions they have a field day, which in this case lasted without a break for weeks.

In the afternoon of 22 January, the Birmingham Pullman, heading for London, was held up at Haddenham by an engine failure in the diesel hauling the 8.55 am Birkenhead train just in front of it. When Control got the news it was already too late to do anything about the Pullman, because it was hot on the tail of the 8.55 anyway. But Control could – and did, for this is the essence of its function – think and act ahead to prevent the first cause of delay reacting on the third train, from Aberystwyth. So Birmingham was told the story and the Aberystwyth train was diverted; Southall produced a pilot to help the crippled 8.55, which was pulled out of the way temporarily; then the Pullman went past it, the 8.55 following on.

This sort of action-on-information is normal when conditions are fair. It happens every half hour. But in snow and prolonged freeze-ups it is multiplied twenty times over. “Drifts at point A”, comes the information. What’s the action? Call the snow plough out. Three trains are heading for the drift – which of them can we divert? Too late to stop the first one, but can we do something about the other two? Then, “More drifts at points B and C” – but the plough for that area is already being used. What now? We’ll have to wait. Everybody will have to wait until we can spare it. Something has to give. When things are bad, it’s a question of working from moment to moment, of cutting the suit according to the cloth.

The brutal situation

‘Keep the lines free’. Four short words, like ‘take a deep breath’. But what a host of things are involved behind it. Frozen points, for instance. The snow falls, a man with a shovel pushes it away. The snow still falls, the man still keeps shovelling. One point is bad enough, an endless task in itself as long as the snow keeps on. But twenty points? And only two men because the third (and the fourth and fifth) never got to the station? Can they win? Yes, given half the chance. But they don’t get even that when all anyone need do is breathe on a window and watch it freeze.

One of the trains in the west country ploughing its way through a bank of snow. The photograph was taken from a carriage window by a passenger travelling from Falmouth, and published in the Western Region Magazine

Streamline your services, nurse your motive and man power, cut according to the cloth. More high-sounding words. You have already cut your cloth according to the brutal situation, you have already cut the long-distance passenger services down to the bone, transferred men and locos to the freight side, given top priority to the lines for food and fuel. Yet what happens if those men are driving a steam engine at the head of a freight and even while they are running the injector, which takes the water from the tender to the boiler, freezes solid? (No injector – no water for the boiler. Hot fire under waterless boiler – boom! No engine.) Has it ever happened before? Yes, but not to the extent it happened in the third week in January 1963. It was all over the region. What do you do?

“Well,” said a Welsh driver, “you do the best you can, like. You get a bit of cotton waste, see, and stick it in the old oil can and light it up and see if you can thaw the thing out. You haven’t got asbestos hands, see, with which to pick up red-hot coals from the fire now, have you? So you do the best you can. If you don’t win, you have to drop the fire. You’re dead then, see. Dead as a duck. You sit there and wait for help – after you’ve chucked the fire outside with the shovel first. And there’s crazy for you. Sitting there watching a nice big hot fire die in the cold, and you along with it. There’s crazy.”

How do you plan trips for steam engines when all the water troughs on every route are frozen into strips of pack ice? You skip the troughs altogether, of course, and stop at the next station. What happens when the water column is frozen solid, too? You’re dead. Dead as a duck. You do the best you can. Control has to find another engine from somewhere – if Control can, if that one isn’t frozen solid too.

“I can’t do without water any better than a housewife can,” said a restaurant car chef. He pointed at the floor. “My tank’s under there and the pump’s frozen. If I don’t see a 10 lb pressure on that gauge I don’t see water either. What do I do? I get some milk churns, fill ’em before we start off and keep ’em filled every station we stop at. Last week I did about 130 breakfasts, nearly 60 lunches and something like 90 dinners that way.”

“And see that metal lining above the toaster? It should be full of water, otherwise the roof burns away – the water’s an insulator. But there’s been none in it for three weeks now, and no toast for the passengers either. We put rolls in the oven and hot them up instead. No complaints. We do the best we can. You can’t do more, can you?” In January 1963 hundreds of restaurant cars were affected in the same way.

On Paddington’s platform 2 there is a group of men who look after the steam and vacuum pipes on all the trains. They, like every other railwayman at the blunt end of the work in that weather, had no let-up. One of them was holding a train heating pipe against a spout of a boiling kettle. The pipe was packed with ice.

“How many we’ve had like this?” He laughed. “None of us here could count up. Every minute of the day you can have everything come on you like a ton of bricks. It isn’t these pipes so much, it’s the valves on the coach side of them. They freeze up. You can get a train off Old Oak Common, where it’s been heated first anyway, but by the time it’s got here there’s no heat anywhere. That valve on the last coach coming in is the valve of the first coach going out, so when that freezes, and even when you’ve got the engine on, the heat doesn’t get past the tender.

“What do we do? Borrow a blowlamp and try and thaw it out. Trouble is, the steam pipes go under the coach floors and if they get frozen you can’t use a blowlamp there unless you want to set the whole train alight. What do we do then? The best we can. If we don’t win the trains have to go out cold.” January 1963 was the worst they experienced.

Vital test for the shunter

Marshalling yards did not escape the cold. With those bitter winds shrieking across the open ground, perhaps they got the worst of it. The ground at night looks harmless and even. In fact, it’s lumpy and deadly. A string of wagons comes rolling past the shunter, and he runs alongside it, using the pole to uncouple them. Every wagon now, whether full or empty, is vital. And every running step the shunter makes is vital, too. Freezing hands, freezing ground, running feet. One slip . . . No shunter had fun in January 1963. A hammer was often the best tool – to crack the couplings loose. He did the best he could. There was nothing else for any railwayman to do.

A goods train at Southall during the severe weather in January 1963

The factor which made all the difference this year was that we had more consecutive days of sub-zero temperatures (32 degrees of frost in Shropshire during the night of the 23rd) than even in 1947. And, towards the end of January, it was this which began to threaten the freight lifeline, the very aspect of railway transport which had been given top priority earlier on.

Coal turns into concrete

Moving coal at all became a tremendous problem. It froze solid, like everything else, in the wagons and on the ground. Jets of steam did no more than soften the top twelve inches. Firemen had to fight for every shovelful from the tenders. Traders found it impossible to off-load railway wagons, and even if they succeeded the roads were so bad that they never reached the back streets.

So the vital contents of the wagons remained locked in the deep freeze, unusable. So the wagons were useless, too. The collieries kept turning out more coal and, with fewer and fewer wagons to load, were forced to stack on the ground – where it froze. To save what there was to be saved, our restricted services were restricted further still while carriages and engines continually froze as hard as the coal heaps. It was a vicious and critical circle.

Yet for all the difficulties, trains did run, some of them even to time. Coal did move, somehow. Failures in motive power and on the track were overcome, somehow. Even long-distance trains did well – in the circumstances. If you had to go to Wales from Scotland or to London from Penzance, you could – in spite of the fact that everyone knew, in the third January week, that we never had it so bad.

Was there no more than very cold comfort here? Yes. The public was appreciative. In the worst of the weather double the usual number of people wrote in to say so. One excerpt can speak for them all from the father of a teenage daughter who was travelling to Truro early in January: “When some people quibble about rail fares I say this journey and the relief was worth £20 to me and I thank everybody responsible.”

Who was responsible? The men on the line. They did all right. Better than that, they did marvels.

TUESDAY 14 FEBRUARY

The BRWR Staff Association

Those who regularly visit our blogs based on treasures in our Great Western Trust collection, can refer back to our 28 July 2020 entry on the Great Western Railway’s Staff Association Annual Musical Festival in 1939, and the illustration of the later, British Railways Staff Association leaflet. Just click on the ‘Tuesday Treasures Index' box above to find the link.

With the recent arrival at Didcot Railway Centre of D1023 Western Fusilier on loan from the National Railway Museum, it prompted us to devote this Tuesday Treasures Blog to illustrate the cover of the BRWR Staff Association quarterly journal for autumn 1972, the series of which was very strikingly entitled “Western Enterprise” after D1000 the class leader.

We believe that this journal began in 1966, and we also have the summer 1977 edition, in which its contents lament the final withdrawal of the Western class hydraulics! However, we do not know precisely when it ceased publication, nevertheless it is important to record that in 1990 when the BR privatisation was imminent, a new staff organisation was born, The National Association of Railway Clubs, which absorbed both the GWRSA and the LMSSA and is very much alive and providing the widest range of advice and support to local and regional staff recreational bodies throughout the UK.

Returning to our Autumn 1972 journal, it is a remarkable, and now very much ‘a thing of the past’ that it continued the long established recreational events, drawing upon the GWR’s activities, including the annual Exhibition of Arts and Crafts, and all its recorded photos and commentary on the prizes awarded. The most striking aspect of these awards, was that so many were to award cups and the like in the names of many long retired GWR Senior Officers and Directors and that the physical presentations were given by the wives of such now retired Officers. One prime example was that of the wife of F W Hawksworth, the GWR’s last Chief Mechanical Engineer.

Yes, very much in our age ‘a thing of the past’ both that senior officers attended such events, and that the staff continued to support such recreational events with enthusiasm. Can we even imagine today’s corporate companies having such commitment, or their employees having the same attitude to engage in off-duty recreation on such a scale? Our Great Western Trust collection, provides a vast array of material of that GWR and then BRWR commitment by staff and managers, and give us pause to reflect on their disappearance, probably most unlikely to be seen ever again.

D1000 Western Enterprise in a photograph issued by the Swindon Drawing Office on 27 February 1968, when the loco was in blue livery with yellow ends

TUESDAY 7 FEBRUARY

Calligraphy at its Finest

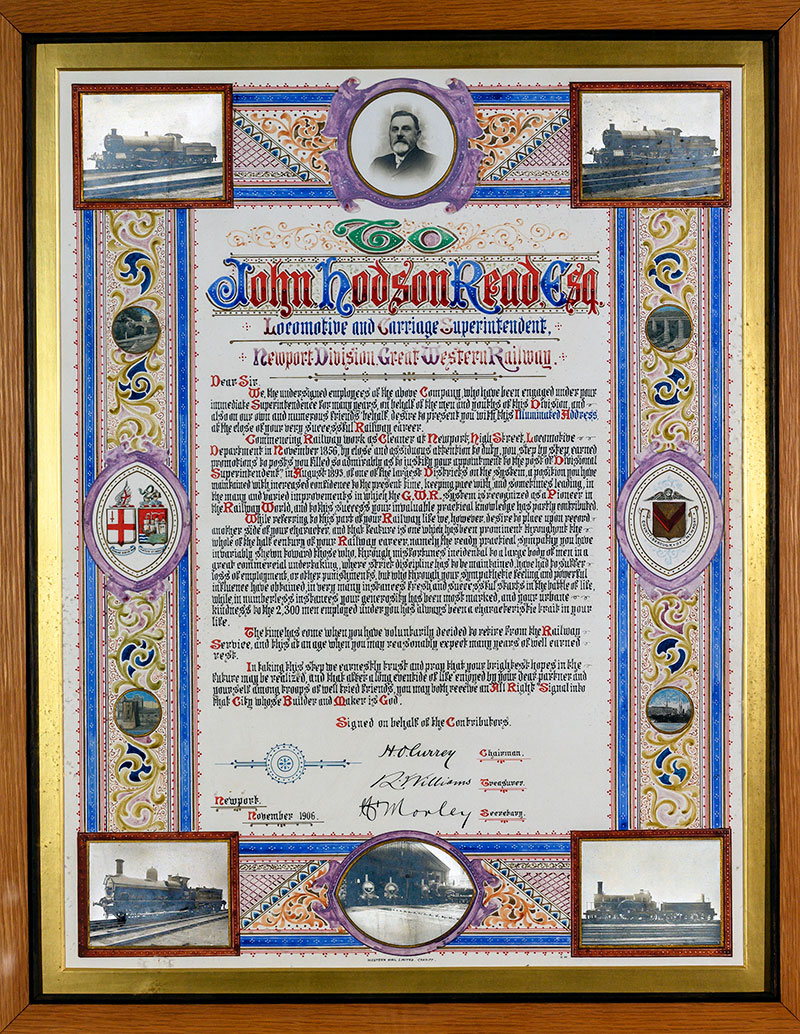

John Hodson Read was born in 1841 and began his fifty years of railway service with the South Wales Railway as a cleaner at Newport in 1856. In 1863 the company amalgamated with the Great Western Railway, and J H Read passed through the various grades of fireman and driver. In a remarkable career he was the Royal Train driver when Queen Victoria was shot at in 1884 at Windsor, and was also in charge of the first train to pass through the Severn Tunnel.

No 190 was built as a 4-4-2 in September 1905 and given the name Waverley in 1906. She was converted to a 4-6-0 in November 1912 and renumbered 2990 in the Saint class. She was withdrawn in January 1939

He was associated with the Mechanics’ Institutes at Pontypool Road and Tondu and was also keenly interested in ambulance and temperance work

John Hodson Read’s photograph on the address

Mr Read retired on 14 November 1906, his sixty-fifth birthday, as the divisional locomotive superintendent at Newport, one of the most important divisions on the GWR. This wonderful illuminated address together with a large silver salver presented to him upon his retirement is testament to his popularity with his staff. He had a long and happy retirement and died in May 1927 at the age of 85.

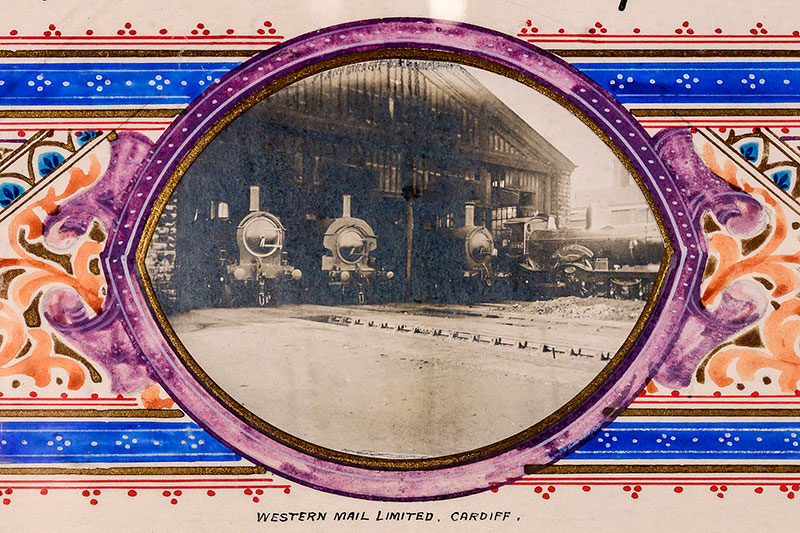

Newport High Street engine shed had been built by the South Wales Railway

The address carries photographs of Mr Read together with locomotives he would have worked on and carried responsibility for. The lower image is of Newport (High Street) shed which closed when Ebbw Junction shed was opened in 1915. Discernible on the right is Duke class loco Fowey.

The silver-plated presentation salver is extraordinarily heavy

Both the address and the salver were generously donated to the Trust in 2022 and will be on display in the Museum later this year.

A close up of the inscription on the salver

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.