Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - January 2023 - Going Loco - January 2023

Going Loco - January 2023

FRIDAY 27 JANUARY

Wonderful Winter Wagons - The Emergency Services?

There is much that is similar to the roads and the railways. There are vehicles just for passengers, vehicles for goods and there are some vehicles that are for undertaking some service or other. It could be maintenance of the road, keeping signs and signals in good condition or it could be for emergency situations…

There were several types of railway vehicles that were used for dealing with emergencies. When we had a chat about the PYTHON CCTs back in July 2022, we discovered that during the Second World War, No. 560 was adapted to become what was, to all intents and purposes, a fire engine. Pumps, a coach for crew accommodation, tools and all were brought together to help fight the incendiary bomb menace. This was an exception rather than the rule, however.

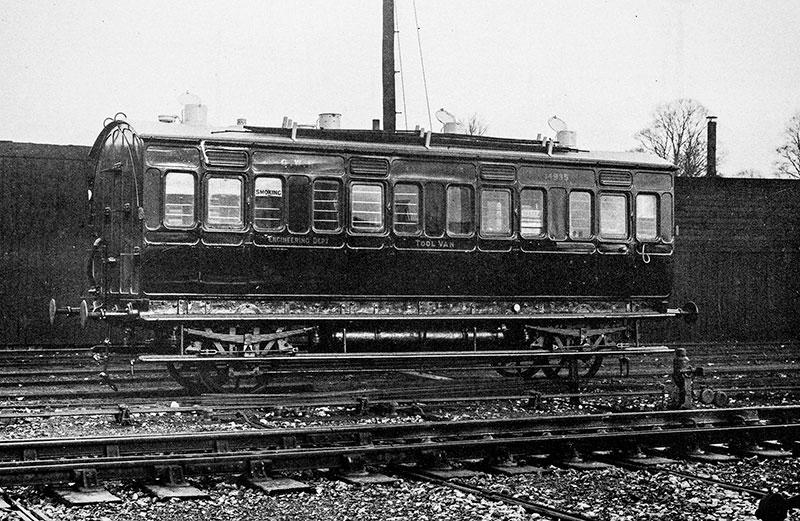

A second class four compartment 4-wheel carriage dating from the 1880s, converted into an engineering department tool van in December 1906. Bars on the windows help prevent the contents smashing the glass

The coaching stock wasn’t immune from this sort of thing either. Ambulance trains were a common thing in both world wars. Full medical facilities on wheels. Less like an ambulance and almost a mobile hospital. Our SIPHON G No. 2796 was a stretcher bearer in the Second World War, and Churchward ‘toplight’ brake third No. 1159 served in ambulance trains in the First World War and then being converted into medical officer’s coach in 1945. Although, these were duties that were neither normal or long lasting.

A detail from a photograph taken in September 1934 showing the Didcot engine shed breakdown train’s riding van. Again this has been converted from a carriage

There was one emergency job on the railway however that was a constant throughout its history. That is the job of the breakdown train. The worst thing that can happen in a running day is that your train falls off the track. Getting a train back on the track is not an inconsequential task. You thought it was annoying when your Hornby stuff came off the track… Rather than the ‘hand of god’ simply coming down into a 4mm scale world and lifting back on, what you need is tools and people.

The Plymouth Laira engine shed’s riding van, with 2-6-2T No 4408

So how do they get there? Well, there was a small, purpose built fleet of vehicles that were crafted by the Great Western for just such a task. They were produced and operated largely in pairs and were known as tool vans (also known as breakdown or pilot vans) and riding vans (also known as tender vans). The tool vans were basically travelling workshops and tool boxes full of all the kit needed to get the unfortunate vehicles back on the track. They also had small derrick cranes at the double sliding doors to lower and then recover the heavier items of re-railing equipment. They possessed a series of glazed skylights in their roofs to provide daylight on proceedings inside.

Tool van No 1, at Didcot Railway Centre

There was an end door at one end and this was the end coupled to the riding van. The idea with the riding van was to provide some creature comforts for the gang of men working at the incident, who might be away for a while if the incident was a big one. Inside, they were much like a caravan. They had long bunks that could double as seats, a fold down table in the middle between them and a cast iron stove for heating and no doubt warming a kettle or a frying pan. All the windows had blinds and they were equipped with gas lighting. Whilst not luxurious, they must have been extremely welcome refuge for the guys in the field so to speak.

Riding van No 47, at Didcot Railway Centre

They had wooden planked bodies and were built on the frames of old 4 or 6 wheeled passenger coaches which lead to a small amount of variation in the fleet. This was also done as it meant that the vehicles were fully fitted with vacuum brakes and therefore were purpose built to travel at passenger speeds. Whilst it is doubtful they would travel in passenger trains, they obviously need to get to the incident as fast as possible. As such they were painted in the livery of the brown vehicles. There was a twist in that the ends were painted red to denote their special purpose. Black frames and a grey roof completed the look.

Riding van No 56, at Didcot Railway Centre

They started to be constructed from the early 1900s. Because perhaps of the reuse of the old chassis, they didn’t get diagram numbers like regular freight or passenger rolling stock. There were also a small batch of bogie versions of these vehicles and these were combined mess and tool vans. They had four compartments, the mess area, a compartment for the officers in charge, the tool and workshop area and the guard’s compartment. There were examples of tool and mess vans stationed at strategic points all around the GWR system so as to be ready for action. They all proudly carried roof boards proclaiming their home base and would read ‘LOCO CARRIAGE & WAGON DEPT’ and then the name of their allocation. They would sometimes run in conjunction with a crane and sometimes just in their pairs.

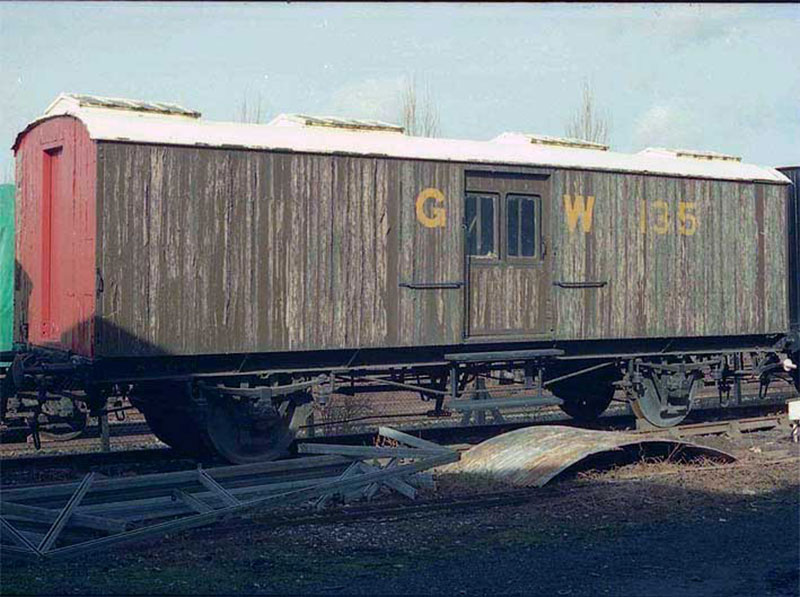

Tool van No 135, at Didcot Railway Centre

They were extremely useful and solidly built and therefore lasted a very long time, still being in service in the 1960s. Their utility lead to them finding further use as the railway preservation movement took off. As a result, quite a large number of these vehicles found gainful employment beyond their normal service lives. So much so that Didcot is home to No less than two pairs! We have tool vans Nos 1 and 135 and mess vans Nos 47 and 56. They continue to do their jobs as well. Another fine example of a solid investment in rolling stock by the Great Western Railway!

FRIDAY 20 JANUARY

Wonderful Winter Wagons: Your Chariot Awaits…

There are a number of vehicles which are signatures of the Great Western Railway. The Kings and Castles, the pannier tank, the 14XX class and Autocoach, and so on. The freight arena is no different and the signature vehicle for a shunting yard of any great size is the shunter’s truck, sometimes nicknamed ‘the Chariot’.

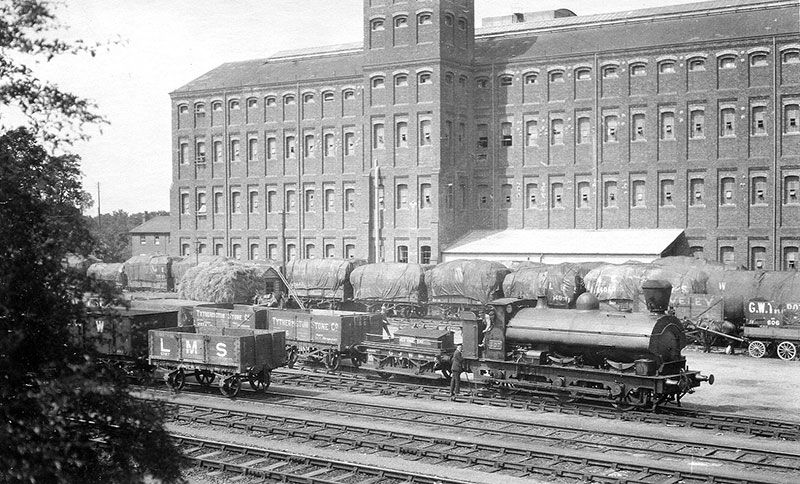

The Provender Yard at Didcot with 0-6-0 saddle tank No 307 coupled to a short-wheelbase shunter’s truck. The photograph was taken between 1922 and 1927 when No 307 was fitted with a saddle tank and spark arrestor chimney

This is a fairly unique bit of rolling stock. It’s all based upon the vast distances that a shunter would have to walk in the medium to large marshalling yards across the system. When you think that even a small yard such as Moreton Cutting (on the outskirts of Didcot, London end), was somewhere between ¼ and ½ a mile long, you start to understand just how far you might have to walk to collect all the wagons you need to make up a train.

0-6-0 pannier tank No 3653 shunting in Didcot West Yard on 22 March 1959. The pond which provided a reservoir for the water tanks on the Provender Building and the engine shed’s Coal Stage is behind the loco and shunter’s truck. Photo by Ben Brooksbank

Wouldn’t it be great for the shunter if he has some sort of mobile platform thing with somewhere for him to stand? The sort of thing that you could hook up to a locomotive. Add onto that a handy toolbox and really what you have is a shunter’s truck. Clearly this wasn’t developed purely for altruistic reasons. The company also realised that things would be speeded up considerably if the loco crew weren’t waiting for the shunter to walk around. Shunting could happen faster!

Shunting at Didcot Railway Centre on 30 December 2012

They were really quite useful things. They prevented the shunter having to stand on the steps on the locomotive. One slip here and if you were unlucky, your foot ended up in the spokes of the wheels and/or the coupling rods. The shunter’s truck had running boards along the sides with handrails to match. They also had covers to prevent the foot going ‘wheelwards’. A set of lamp irons so that the engine head code* could be carried and that was pretty much it.

Shunting at Didcot Railway Centre on 25 August 2013

These vehicles have their origins in the broad gauge era and in fact, the evolutionary process that resulted in the shunter’s truck as we know it, is steeped in conversions of old broad gauge wagons into a sort of proto-shunter’s-truck. Quite what the first one was is somewhat lost to the mists of time but they certainly existed by the late 1870s. This process continues on the standard gauge too, also using withdrawn wagons as the base vehicle.

The shunter’s truck lettered for Crimea Yard, which was a coal yard close to Paddington at Westbourne Park

By 1895, the first of the ‘modern’ shunter’s trucks had arrived. These two became diagram M1 in the wagon design index and Nos 41897 and 41898 saw the final additions to the design. Including the foot guards on the wheels. Although the probable reason for their addition doesn’t bear thinking about. Health and safety being very much a reactive rather than preventative exercise in those days…

The shunter’s truck lettered for Southall during the Great Western Society’s 60th Anniversary year in 2021

They were unusual in that they had a short 7’ wheelbase and even measured over their buffers, they only came out to 17’ long. This was of course greatly to their advantage. A short wheelbase and frame meant that they could go round really sharp curves in shunting yards. As these wagons didn’t travel extensively, and were highly prized, the name of the yard they were allocated to was often to be seen painted on their toolboxes. They eventually ran to five different diagrams and the last few were built as late as the early 1950s under British Railways.

Not just for shunters, 1: the truck is taken over by the military in June 2014 during commemoration of the 70th anniversary of D-Day. Pannier tank No 3650 has been fitted with a spark arrestor chimney for the occasion

These last few went back to their roots and were conversions of older vehicles. In fact, the one that was chosen to live with us a Didcot, No 100377, is one of these very vehicles. It started life as a Diagram V14 MINK van** which was built way back in 1923***. It was converted to become a shunter’s truck in 1953. It is presented in a GWR livery despite being 5 years too young! It has become something of a tradition for our Carriage and Wagon Department to occasionally change the allocation name on the toolbox from time to time. It has been ‘allocated’, among other places, to Moreton Cutting, Crimea Yard and is currently assigned to Southall. It is occasionally used for its intended purpose too – carrying on a tradition of nearly 150 years.

Not just for shunters, 2: the Fat Controller takes a ride during a Thomas and Friends event in October 2019

*The headcode for a shunting engine was one red and one white lamp at each end. So they really didn’t know if they were coming or going…

**Yep - those MINKs from last week!

***Meaning it is 100 years old (sort of!) this year!

FRIDAY 13 JANUARY

Wonderful Winter Wagons: Think (more) MINK!

We were looking at the IRON MINKs last time and I did kind of hint that they weren’t the only kind of MINK. There is a lot more to that telegraphic code than metal bodied vans…

The code is something of a catch all and covers quite the range of vehicles. The official list simply says covered goods van. This means any goods vehicle possessing both a roof and walls. It isn’t as simple as that – there are a whole bunch of vehicles in that group that aren’t called MINKs.

A goods train at Didcot Railway Centre in 2013. The leading vehicle is MINK A No 101720. The second van is No 145428, built in 1944 and owned by the GWR 813 Preservation Fund

MINKs came in a variety of shapes and sizes. The regular one was the industry standard of a 9’ wheelbase, 16’ long 4 wheeled van. The heights and widths were experimented with a bit in the early days but a standard 11’ 9½” from rail height was eventually chosen. There were thousands of these vans built and being Swindon standard, many were different(!). Some had the long lever Morton brake while others had the small D/C* ratchet levers at the ends. Some were unfitted while others had vacuum brakes enabling them to run to higher speeds. The variety seems endless. These were all either known as MINK or MINK A.

For larger loads, Swindon started to stretch the design a little. The MINK B was 21’ long with a 12’ wheelbase, as was the MINK C and this design began service in the early 1900s. The lengthened bodies meant that two pairs of doors per side were provided. MINK D was the next step up in size to 28’ 6” long over the headstocks and a 20’ wheelbase. All these wagons, despite their size, were restricted to 10 tons in weight but the last of the big MINKs, the MINK G.** was rated to 20 tons. These 1930s creations were the big ones – 30’ over the headstocks and 1,640 cubic feet in load carrying capacity.

All of these MINKs had all sorts of different types of body frames and door styles. Sometimes the doors of an earlier van were replaced with a later style. End ventilators of several different flavours were used and updated as time went on too. There is just too much to write about in a Going Loco but suffice to say, look at some photographs and you will see just how varied the standard designs of the MINK van was!

Alongside IRON MINK No 11152, their ubiquity has led to four other examples of MINKs in the collection. One of them is what is known as a grounded body. This is a withdrawn van without wheels that is used as a shed or store. This was a common practice on the railway and in public use as well and many can still be seen in odd corners of the UK. Ours, No 89268, is a diagram V14 example built in 1912 that was part of the deal when we purchased No 6023 King Edward II. It was being used as a store in Bristol and continues in that vein at Didcot.

We have two of the MINK A variety vans both to diagram V14. No 101836, built in 1925, is presented as a general service van, or one that would have transported whatever came its way. No 101720, built in 1924, represents one of those vehicles that were set aside for specific duties. The conveyance of flour could be a somewhat complicated business. Contamination of what is a foodstuff is clearly not a great idea so keeping it away from other things is useful. However, if a bag has an accident and bursts open, those receiving the flour won’t be too worried if their goods has a bit of flour on the outside. The purchaser of a brand new easy chair might have a different view on the matter however… As a result, some vehicles were allocated to specific traffic. To add a little local colour, No. 101720 is lettered with:

FLOUR TRAFFIC ONLY

Empty to

WANTAGE ROAD

The last of our MINKs is the big one – the mighty MINK G. Ours is No 112843 which is built to Diagram V22 and was completed in 1934. This has been looked after as a stores wagon for many years and it has become part of the lore of the GWS Heavy Freight Group. The story of the MINKs is the story of so much of the culture and sights of the steam age railway. Once very common things that are largely gone forever. Unless you are part of a group that collected a load of this stuff together and now have a fantastic train set, errr, I mean important museum collection, of rolling stock just like this(!). We are so fortunate that the founding fathers (and mothers – there were a few) of the society set out to have such a broad collection, keeping all aspects of that once daily life alive in a corner of Oxfordshire.

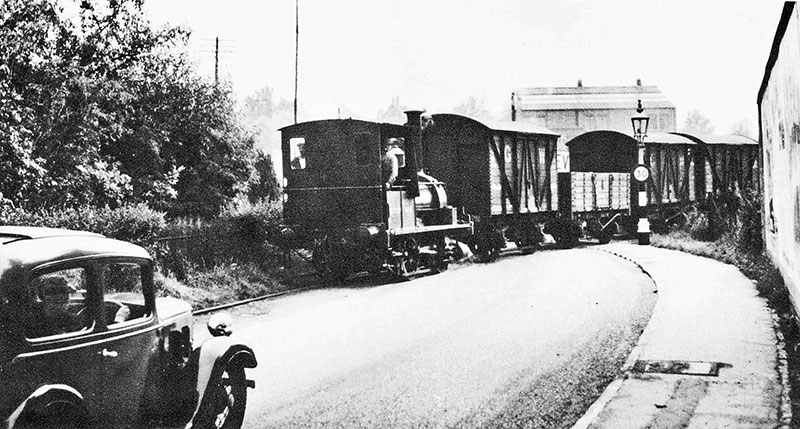

Wantage Tramway No 5 hauling a goods train into the town. No doubt some of these vans will be used to take consignments of flour

FRIDAY 6 JANUARY

Wonderful Winter Wagons: Think MINK!

Happy new year to all the readers and I hope we all had a good holiday.

It’s that time of year again! January is wagon month. Although, it has to be said that I’ve not really held to that last year – quite a few well out of season wagons in that lot… So, to business. One of the telegraphic code names most associated with the Great Western Railway (alongside TOAD for the brake vans) is that of MINK. There were several different flavours of MINK, but one of the most commonly associated with the Western was the metal one. Welcome on stage IRON MINK!*

Shunting a mixed goods train in London, about 1914. The third vehicle behind the locomotive is an Iron Mink, the fifth vehicle, No 16204, is a regular wooden-bodied Mink

The term IRON MINK was wholly unofficial. The code MINK covered a wide range of different vehicles and the fact that this particular sub-group was made of something different was of little consequence in the vast majority of cases. They mostly carried the same goods as their wooden-bodied brethren and were pretty much interchangeable. The design goes way back to the 1880s – a time when the Great Western were still running some broad gauge trains. The first two were ordered on an experimental basis. They had many innovations, not least of which was the fact that the body of the vehicle was made of metal. The other big change was the ‘C’ section channel used as the outer frames of the vans.

Their construction was ordered in 1886 but was delayed until 1887. They were so needed by the GWR that the order was supplemented for another 100 units to replace worn out freight rolling stock. The first two were built in May and June but by the end of the year, 94 of the large batch had been built. The last of that batch were delayed again until May and June of 1888 when the final six were completed. They had a 9’ 6” wheelbase, were 16’ 6” long and had an 8 ton capacity.

The design was being developed in 1887 and the ruling was that most 4-wheel goods vehicles should be standardised in a wheelbase of 9’ with an overall length of 16’. This meant a great advantage in standardised parts – theoretically at least. The first of these were ordered in February 1888 and was for another 100 wagons. Such was their success, by September 1889 over 1,000 of their type were in service! The numbers just ballooned and by 1901 there were nearly 5,000 IRON MINKs.

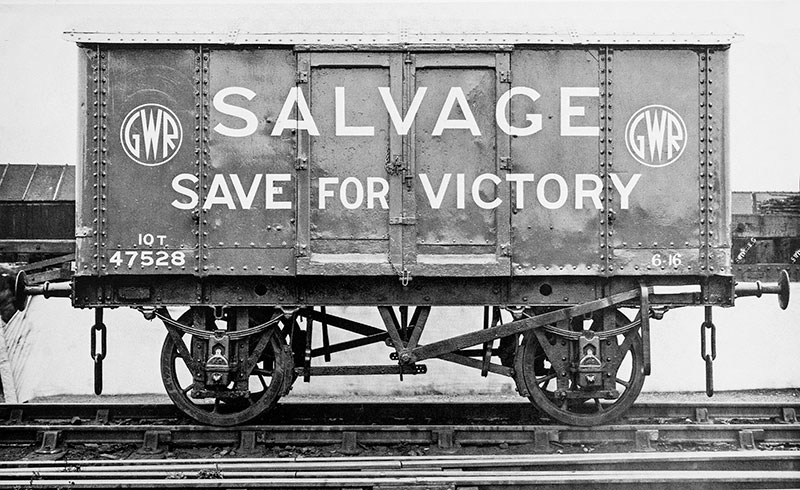

No 47528 was one of the Iron Minks use to collect salvage for recycling during the second world war. The body has evidently had a hard life and been extensively patched

Given their longevity, they were bound to evolve as time went on. Grease lubricated axle boxes became oil lubricated axle boxes. Brakes were updated – the original design only had brake shoes and a lever on one side and this encouraged shunters to cross between wagons to pin them down. This was a source of a great many maiming and life-ending incidents and it resulted in legislation that demanded brakes on both sides. This was done by adding a single brake shoe and lever on the opposite side. Our example is one so treated.

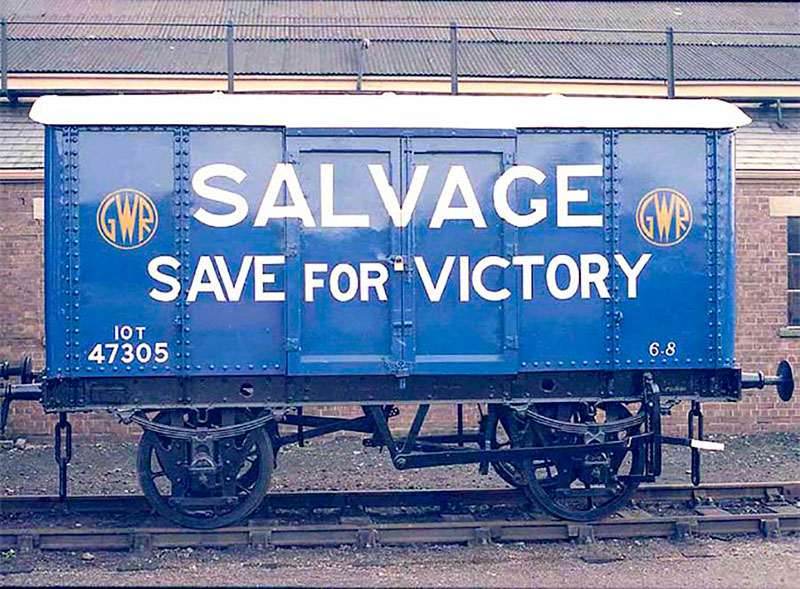

For a while in the 1990s Iron Mink No 11152 at Didcot carried the blue livery and identity of salvage van No 47305

A small few were passenger fitted and had vacuum brakes and screw couplings, enabling them to run in faster trains. Some had wooden doors as replacements for metal ones and others still were converted into gunpowder vans. This was covered in November 2022 in the blog on the transport of explosives so I won’t rehash it all again! They also served in WWII as advertising for the scrap drives. Material of all kinds was in short supply. To encourage recycling, two (Nos. 47305 & 47528) were painted in a blue livery with ‘SALVAGE’ ‘SAVE FOR VICTORY’ emblazoned on their flanks. They collected paper from around the GWR system to be pulped and used again. I guess nothing is new!

The design was very popular with other railways too and when the grouping occurred 100 years ago as I write this, the GWR absorbed several hundred very similar vehicles from the Welsh constituent companies.

There were even monsters hiding in the ranks of the IRON MINKs. The Bogie IRON MINK Fs were built at the end of the IRON MINK era and were huge in comparison to their 4-wheeled cousins. There was much discussion at Swindon at the time that centred around whether it was a great idea to:

a) build larger capacity goods wagons, and

b) build covered good vehicles out of metal.

One of the bogie Iron Minks. These were fitted with vacuum brakes to work in overnight express goods trains

As if to push these ideas to the extreme, these 36’ long, 30 ton versions were trialled. They never really caught on and only eight were built, none of which made it into preservation.

These vehicles lasted well into the nationalisation era and continued to serve for a long time. Eventually all good things come to an end and the IRON MINK experiment faded away. Their ubiquity and durability meant that a few have survived to be preserved on the heritage railways of the U.K. Our collection is no exception!

No 11152 has currently been restored to GWR 1904 livery

We have No 11152. It was part of Lot 217 and was built to diagram V6 in 1900. It still looks good – nearly a century and a quarter later. It has worn the interesting blue WWII ‘SALVAGE’ livery but is currently painted in a more authentic scheme representing one of the thousands of vehicles as it would have appeared in about 1904. It’s a fitting memorial to these fascinating vehicles don’t you think?

*With sincere apologies to Mr Dickinson and his colleagues…

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.