Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - February 2023 - Going Loco - February 2023

Going Loco - February 2023

FRIDAY 24 FEBRUARY

100 Years and 4 Castles, Part 4 - The Reign of the Castles

Just a week and a day until the gathering of the most Castles in one place for many, many years. It’s really exciting isn’t it?! Last week we took a look at the early Castles and the development of the locomotive that was to become the more common design of the type.

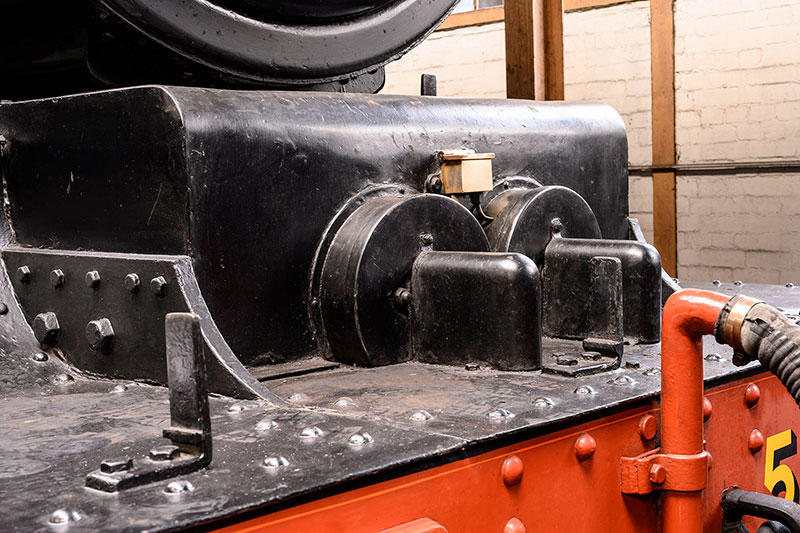

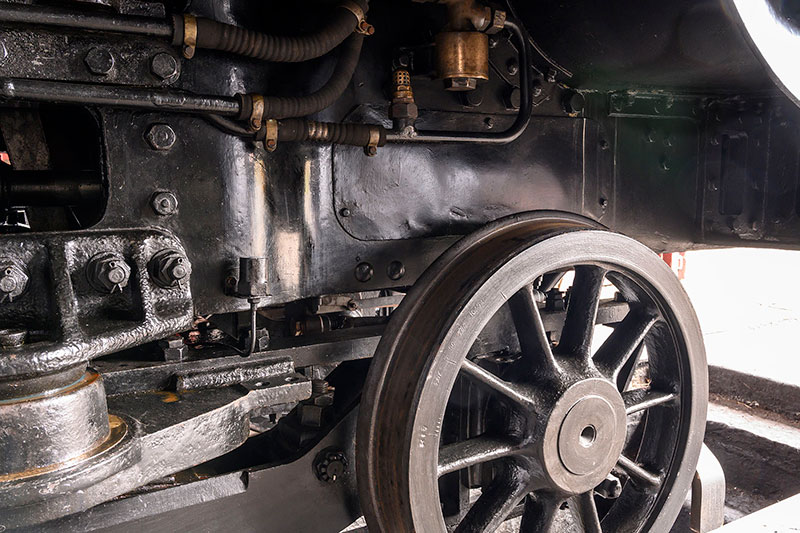

The cover over the inside cylinder valves at the front of No 5051

Let’s take a look at how this engine was shaping up. From the front end, the valve cover made another change to a far more simple design. At the cab, the two small porthole windows present on the early machines, above the top of the firebox, were deleted. They were always troublesome in operation and were not generally missed.

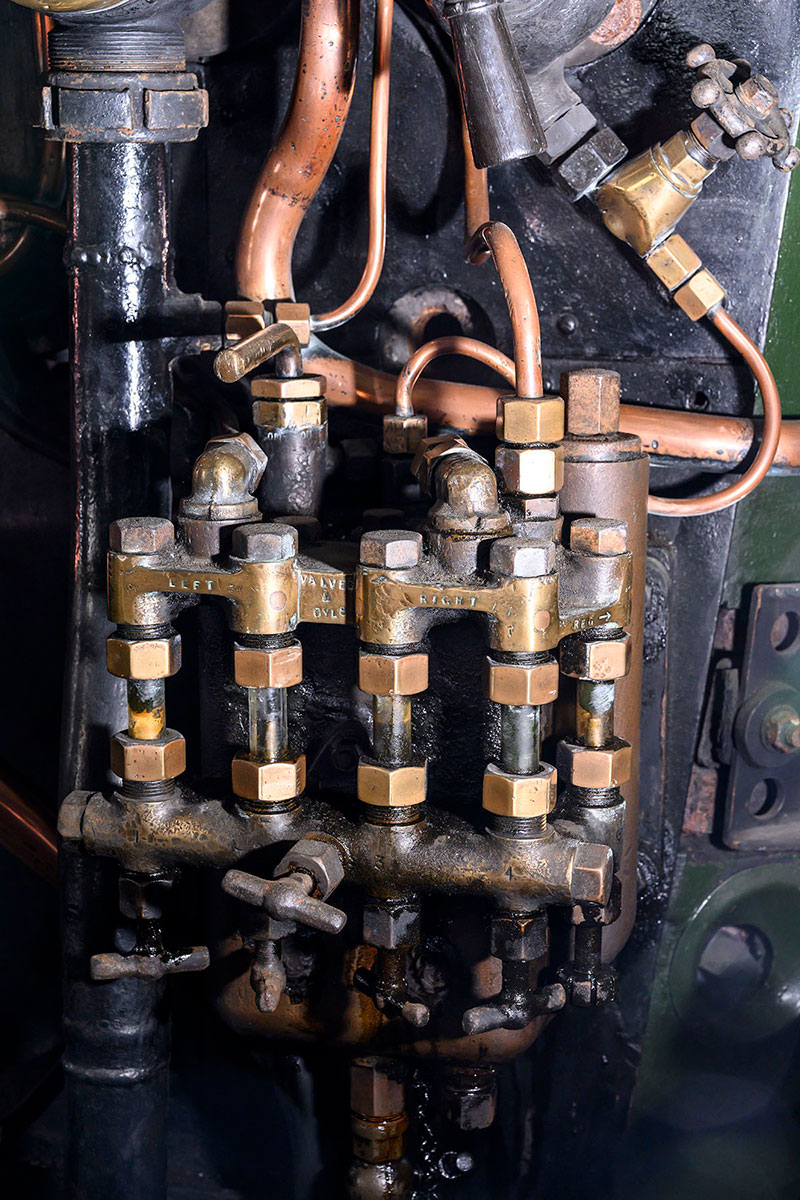

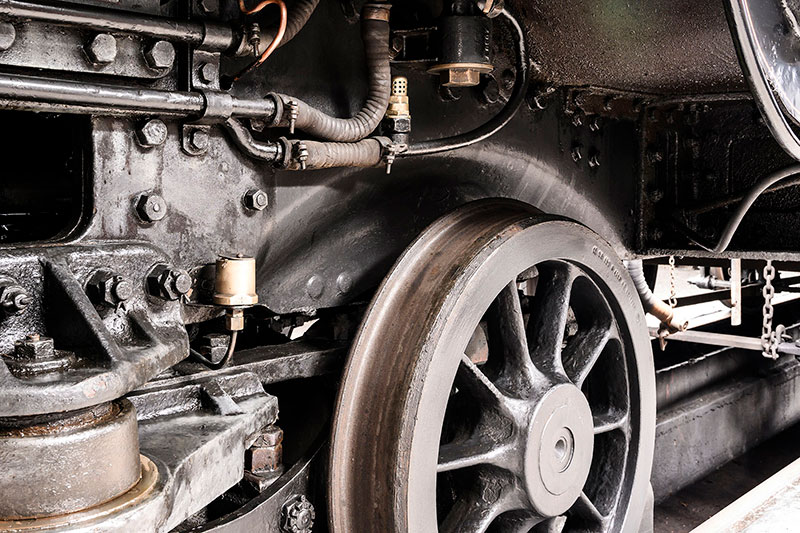

The lubrication for the front end had been updated too. The engines started out with a three-glass hydrostatic displacement lubricator. This counts the number of different valves that can be used to get the oil up to the regulator, the valves and the cylinders. The latter five-glass version simply has more valves. They are arranged slightly differently. The cover on the driver’s side of the smokebox is where two oil lines go into the smokebox and in to the steam circuit. On the five-glass version there is a third oil line that goes down the fireman’s side of the boiler and into the smokebox. This has its own cover too and now you know how to win at being a Castle nerd!

The five-glass lubricator of No 5051

The chimney used on the class was originally of a similar tall design to those used on the Saints and Stars and a lower version was fitted to the later batches of machines. These modifications were cascaded throughout the fleet as time went on.

Tenders had seen a number of changes too. The original Castles, like the rest of the early 1920s tender engines, were typically seen with a 3,500 gallon unit of Churchward design. An intermediate 3,500 gallon unit with higher sides was developed to better match with the new Collett cab sides. It was not built in huge numbers however. While 3,500 gallons were adequate for the period, a more comfortable margin of another 500 gallons of water was felt to be in order. This idea went back to the era of Churchward’s predecessor, Dean, and there were a few 4,000 gallon tenders produced under his management. Collett designed a new version and it is this that the tender type that we most associate with the Castles, Halls, Kings and so on.

Collett is regarded as a very private and austere individual. There are however two incidents in the history of the Castles that show a spark of an almost mischievous sense of humour. Most unlike the image history has handed down to us. The first came in the mid 1930s. The Great Western Railway’s board of directors wanted some of their names to be carried on some new GWR locomotives.

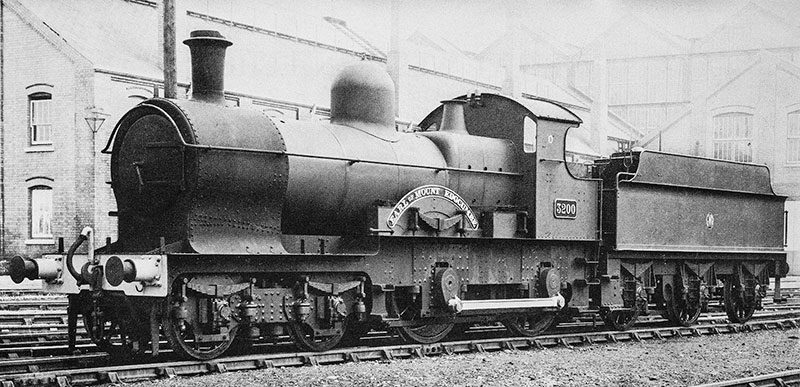

The 4-4-0 briefly named Earl of Mount Edgcumbe

Clearly thinking that this meant Castles, the board members were rather dismayed when the new ‘Earls’ – the rebuilds of the Victorian Duke and Bulldog 4-4-0 outside frame classes (affectionately known as the Dukedogs) – turned up at Paddington for the official naming ceremony. A swift ‘chat’ with Collett later resulted in some of the Castles receiving Earl names. This started with No 5043 which went from Barbary Castle to Earl of Mount Edgcumbe and includes No 5051 Drysllwyn Castle which became Earl Bathurst*.

Earl of Mount Edgcumbe at Didcot during the GWR 175 celebration on 1 May 2010

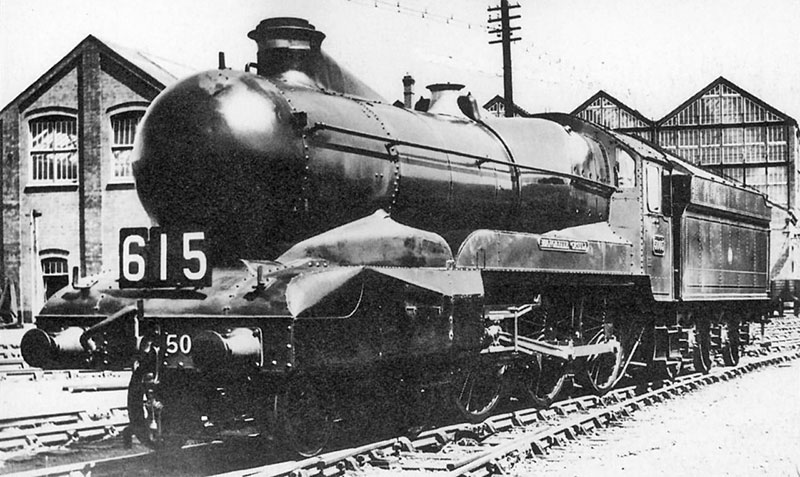

The second came when another edict from the board came down. This time it was streamlining. This has become the latest thing – the Art Deco era was all about those shapes and locomotives such as the LNER A4 class Pacifics were Britain’s railway expression of this. Collett didn’t really hold with such fads as he saw it. The possibly apocryphal tale often told is that he sent an office boy off to get some plasticine. This was duly smeared over a model of a Castle and then sent to be drawn and manufactured. The victims of this experiment were King class No 6014 King Henry VII and No. 5005 Manorbier Castle. Wedge shaped cabs, a hemispherical dome on the smokebox door and a whole host of different panels were attached. These really just got in the way of maintenance and day-to-day operations and they were slowly removed piecemeal shortly afterwards.

Manorbier Castle after streamlining was applied

The Castles were only the top of the pile for a relatively short time. The need for a final upgrade to the design to take on the very heaviest trains resulted in the King class being developed in 1927. The extra weight caused by the developments in power in the Kings meant that they were very heavy and restricted to a very small proportion of the network. The Castles however were far less restricted and it gave them the availability to truly embed themselves in the working of the Great Western.

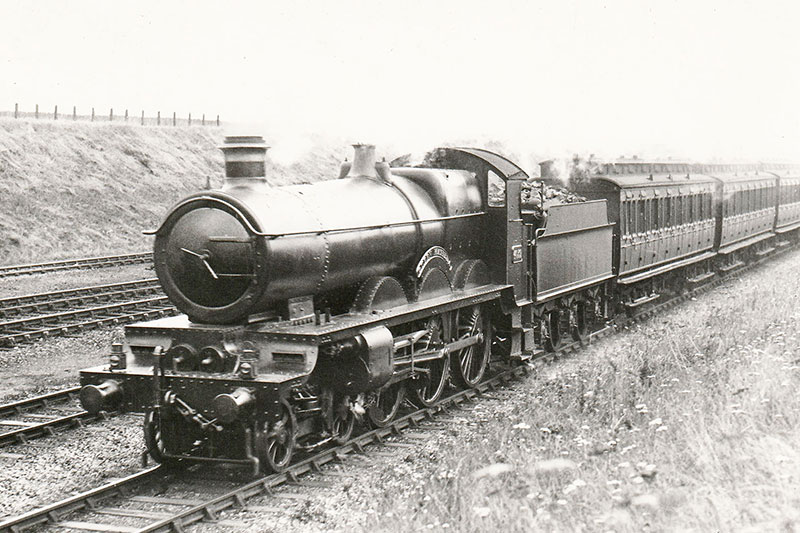

The Cheltenham Flyer being hauled by No 5000 Launceston Castle on 14 September 1931. Driver J W Street and fireman F W Shearer achieved a time of 59½ minutes from Swindon to Paddington

The train that they were famous for pulling was the Cheltenham Flyer. The GWR had run an express from Cheltenham to London Paddington since before the First World War. The advent of the Castles in 1923 meant that their power and speed were able to support making this service progressively faster and it was soon accelerated to the point where it became the fastest scheduled passenger train in the world! The fastest run being performed on the 6 June 1932 when No 5006 Tregenna Castle under the control of driver Rudduck and fireman Thorpe travelled the 77¼ miles from Swindon to Paddington in 56 mins 47 seconds at an average speed of 81.6 miles per hour.

The Cheltenham Flyer being hauled by No 5043 on 22 May 1936, when the loco was still named Barbury Castle

There were well over 100 machines built or converted up to the outbreak of World War II. These ranged from No 4073 Caerphilly Castle to No 5097 Sarum Castle. Nos 5098 and 5099 were due to be built as part of the last pre-war batch, but in 1939 other priorities were taking the place of building express passenger locomotives. There were some dark times ahead for the world at large, but the Castles came through it in the end and we will take a look at the final developments in the class next week.

No 5001 Llandovery Castle towards the end of her career, hauling a westbound stopping train at Goring and Streatley station. Photo by Mike Peart

*Both of which will be on display on the fourth of March!

FRIDAY 17 FEBRUARY

100 Years and 4 Castles, Part 3 - The Castles Arise

Can you believe it? It’s been two weeks of blogs so far in our Going Loco build up to our Four Castles Event on the Fourth of March, and we haven’t talked specifically about the Castles! What a tangled web we weave… Let’s rectify this right now.

So, previously we got to the point where the last of the 40XX or Star class locomotives had been completed. Even as they were finished, a series of sea changes were happening at Swindon. In 1922, The great G J Churchward retired from his position of Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Great Western Railway. He was a very popular character. Very much a man who got involved in all aspects of the work at Swindon.

His replacement was a very different character. Charles Benjamin Collett was much happier to let subordinates tackle day-to-day matters. He also wasn’t the outstanding locomotive engineer that his predecessor had been. He did have an advantage, however, in that he was an outstanding production engineer. This meant he was very good at the optimisation and refinement of engineering manufacturing. This lead him to realise that the designs that Churchward had come up with were, for the time, leagues ahead of the other railways in the UK. The locomotive standardisation policy that he and Churchward had forged together was also unlike any railway in the UK possessed in terms of its all-encompassing nature. All he had to do was to build upon it.

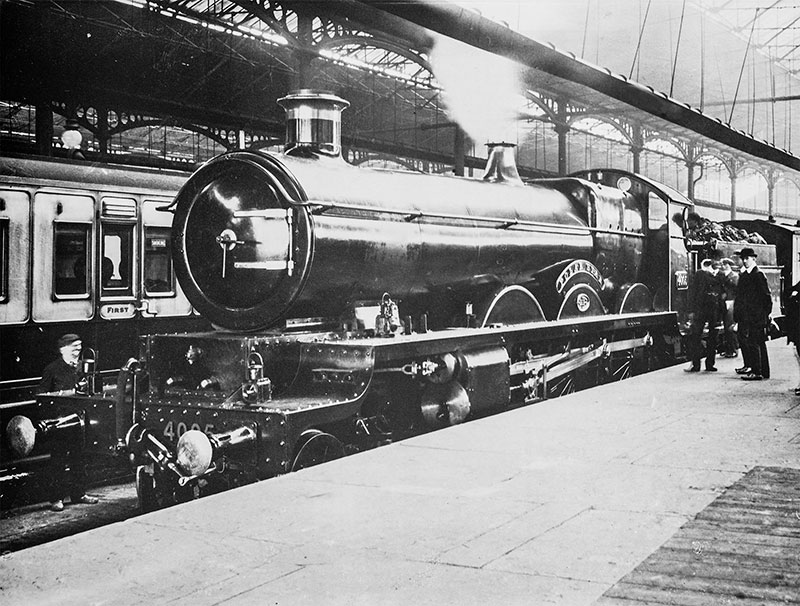

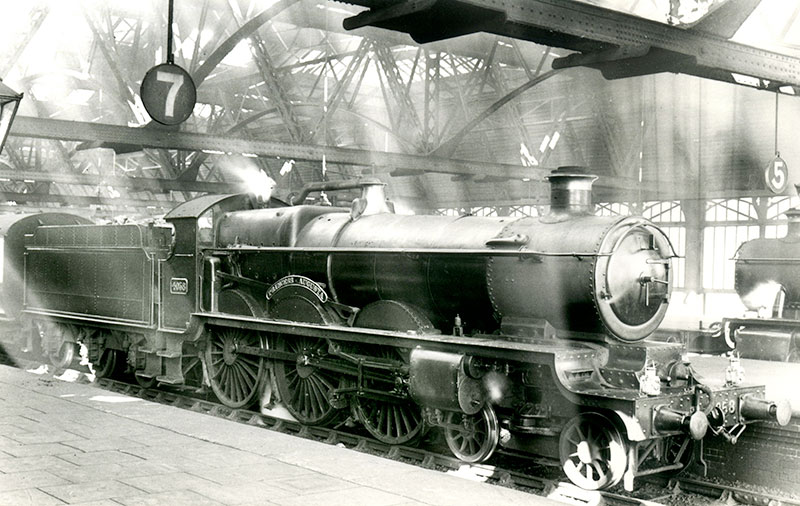

The brand new Caerphilly Castle on display at Paddington station in August 1923

This conservative approach has been much criticised, but the big point that most of those doing the criticising fail to grasp is that he was working for a commercial organisation. The idea was to make money. No doubt, Churchward’s programme cost a LOT of money and Collett could protect that investment by putting it to full use. Did this mean that the huge lead they had gained was slowly eroded away? Yes. However, designs like the Castles and the Halls were still relevant enough for them to be built new into the 1950s. They were the right machines for a steam driven Great Western Railway. Churchward and Collett together proved that.

Even as the last of the Stars were being built, they were starting to be pushed a little too hard – victims of their own success. The efficiency and style of the GWR attracted a lot of customers into the 1920s. The trains got bigger and heavier. The gap between the tractive effort that the Stars were capable of delivering and the amount of effort required to pull the trains was getting smaller and smaller. Taxing engines harder and harder has a limit. You can only go so far until something gives. This wasn’t going to happen under Collett.

He also wasn’t going to need to spend huge amounts of time, effort and money to rectify this problem either. The Star design had been hard won and was fundamentally sound. It just wasn’t powerful enough. Churchward had looked into fitting the Standard 7 type boiler from the 47XX class 2-8-0 fast freight machines to a Star chassis. The problem here was that the weight of the boiler caused the calculated axle weight of the locomotive to exceed the 20 ton limit set by the engineering department.

No 5000 Launceston Castle in grey livery to make the details stand out in the photograph. Some retouching has been carried out on this original GWR print, including adding the GWR roundel on the tender

Collett had to sort out the problem, so the ‘enlarged Star’ was revisited. The boiler needed to be larger than the Standard 1 of the Stars to give the engine a bigger reserve of steam to draw upon when working hard. The engineers took the bull by the horns and they designed a new, lighter boiler – the Standard 8. The increase in steam available from this meant that larger cylinders could be fitted. The Stars had four 15” diameter × 26” stroke cylinders. The ‘enlarged Stars’ had the cylinders increased to 16” diameter but the 26” stroke remained the same to match the original design. The frames of the engine were extended rearward and this enabled the fitting of a new, larger cab with side windows.

Due to the confidence already gained in the design, an extensive trials period as was undertaken with No 4000 North Star was felt unnecessary. The first of these machines was built in August 1923 and four months were allowed to give the engine time to bed in and reveal any faults that the changes might have caused. None were found and No 4073 Caerphilly Castle became the first of a great family of express passenger engines. There were two things to notice here. Firstly, the number didn’t start from ‘zero’ so to speak. The last Star was No 4072, the first Castle was No 4073, such was the similarity between the two types. Secondly, the last Stars were named after Abbeys on the GWR route. These new machines were named after Castles. And so it began…

The first batch of Castles was nine strong and included our very own No 4079 Pendennis Castle. We have discussed the impact made by the design when No 4073 and later No. 4079 were displayed at the British Empire Exhibition in 1924 and 1925, but needless to say the influence on the locomotive engineering community was profound. The efficiency of the locomotive design was unmatched at the time and it really was certainly the best express passenger locomotive in the UK, perhaps the world, at the time.

The immediate success of the first nine lead to a second batch of Castles being ordered shortly after the last of the initial machines were delivered. There were a few changes however. Ever the production engineer, Collett wanted to make the production process easier. The bogie brakes that were championed by Churchward had been fitted to the first few Castles. No 4079 still has the holes in the bogie frames where they were fitted. Collett’s experiments found that they were having no appreciable effect on the braking of trains, so he had them removed. Much to Churchward’s chagrin some sources say…

No. 4079’s joggled frame to clear the front bogie wheels

The other big change was also at the front end. The Stars and the first nine Castles have what is called joggled frames. The inside cylinder block is narrower than the distance between the locomotive frames. To fit with this, the frames bend inwards and then immediately outwards again – or are joggled. This is done to allow the bogie wheels to swing side to side on curved track. So tight is the space that the inside cylinders on these locos need a hole cut in the side of the frames to allow for the strengthening ribs on the side of the cylinder block to fit.

Collett did away with this by designing a new inside cylinder block that fitted exactly to the inside dimension of the frames. To allow the bogie wheels to turn, small dished impressions were pressed into the frame plates. A number of complex engineering steps were thus averted! It’s when you start to hear about thinking like this, you get to understand just how clever and capable Collett and his team were.

No. 5051’s dished frame plate to clear the front bogie wheels

For full nerd points, if you look at the valve covers below the smokebox door, you can tell if it’s an engine from batch one or two. The fluted or Vauxhall* style cover from the Stars was continued. It’s the same size for the early Castles but wider on batch two engines. Once you get your eye in, it becomes obvious… These engines are Nos 4083 to 4092.

This was also the period when the rebuilds from other classes began. The first was the only Pacific or 4-6-2 locomotive that the Great Western ever built, No 111 The Great Bear. This engine really deserves a Going Loco of her own but she ended her days as a Pacific in 1924 and emerged as a Castle in September of that year. How much of the original No 111 was used in the rebuild is open to debate but estimates range from not much to nothing but the number plates! Even the name was changed to Viscount Churchill.

No. 111 Viscount Churchill, rebuilt from The Great Bear and seen here towards the end of her career. She was withdrawn in July 1953

Star Class No 4009 Shooting Star was ‘Castle-ised’ in April 1925 but the process here was a lot simpler. New cylinders, extended frames with a new cab and the new boiler gave the required upgrade. In 1936 she became No 100 A1 Lloyds. No 4016 was also rebuilt in October 1925. In January 1938, she was renamed from Knight of the Golden Fleece to The Somerset Light Infantry (Prince Albert's). This engine was clearly going for the ‘largest, heaviest name plates on the Western’ record…

No. 4009 Shooting Star after conversion to a Castle

We will carry on with this tale next week.

*They were given this name because they brought to mind the sculpted radiator covers and bonnets of pre-WWII cars made by this manufacturer! The bonnet decorations continued as chrome strips into the 1950s.

FRIDAY 10 FEBRUARY

100 Years and 4 Castles, Part 2 – Per Ardua Ad Astra*

So last time we began the build-up to our Four Castles event on the Fourth of March by taking a look at what is effectively ground zero for the class – No 40 North Star of 1906. So, the next step in the road to the Castles was the Stars. The production series of the original 4-cylinder 4-6-0 was a little different from the prototype and saw much development over the 73 further units produced. Let’s take a little walk among the Stars…

No 4006 Red Star was one of the original batch of the class built in 1907. She was withdrawn in November 1932

The prototype had been extensively tested and, although it had always been the case that the engines were destined to be 4-6-0s, the very slight occasional hint was there that as a 4-4-2, North Star couldn’t quite reach her potential. The extra ‘sure-footedness’ of the extra set of driving wheels really made the difference. The other big difference was the valve gear. No 40 had a rather intricate scissors type valve gear. This was complicated, not easy to either set up or maintain.

One of the few classes of GWR locomotives to carry outside Walschaerts valve gear, the 15XX class of pannier tanks were introduced in 1949. No 1501 is now preserved on the Severn Valley Railway, and was photographed during a Timeline Events photo charter at Didcot in 2015

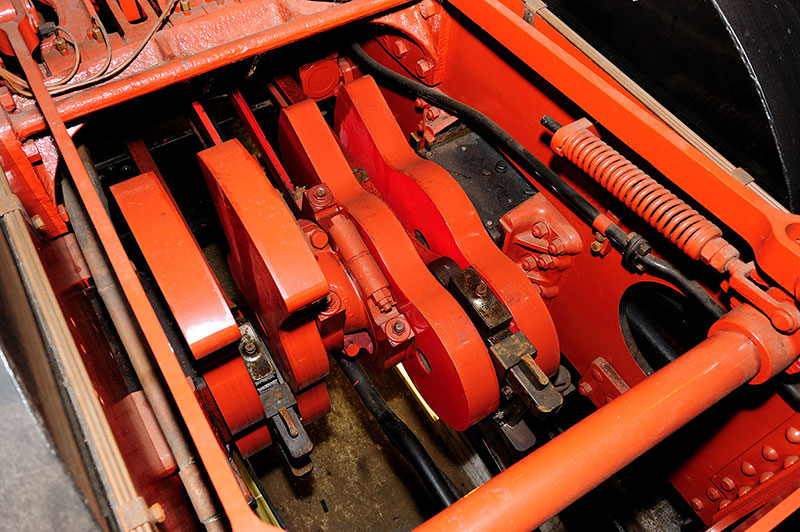

The solution came in the form of Walschaerts valve gear. The French de Glehn 4-4-2s had this arrangement but it was mounted externally. Churchward hid that sort of thing away so it couldn’t be seen. The valve gear was essentially the same as you see on the outside except it’s kind of inside out. But inside. A picture will be placed here to explain this madness! The only thing that changed was that the gear was driven by eccentrics with eccentric straps to transfer the motion. They were placed between the cranks for the two inside cylinders. To prevent more valve gear on the outside, rocking arms transfer the motion to the outside valves.

The drive for the inside Walschaerts valve gear on a GWR 4-cylinder locomotive was taken from eccentrics between the cranks for the two inside cylinders. This photo shows the crank axle of No 6023 King Edward II, but the principle is the same for the Stars and Castles

A screw reverser gave very fine control of the valve gear and the first batch of ten also gained various other modifications as time went on. One of the first of these developments being the beginning of superheating.** No 4010 Western Star was fitted with an American design from Cole. They also gained the ‘Holcroft Curves’. The early Saints had been criticised as looking too stark and modern(!) so draughtsman and engineer Harold Holcroft suggested adding the sweeping curves at the buffer beam and under the cab.

No 4005 Polar Star, built in February 1907, at Euston station during the locomotive exchange of 1910. This locomotive was withdrawn in November 1934

Nos. 4001 to 4010 were all named after the original broad gauge Star class machines of the 19th century. They still had a certain amount of experimenting to do and one thing not taken forward was the swing link suspension on the bogies. Again, too much trouble… The second batch of ten were named after orders of chivalry and are remembered as the Knights. No 4011 Knight of the Garter was fitted with the first of the home grown Swindon superheaters. The number 1 version was quickly replaced by the equally inspiringly named number 3 design which again, remained standard for much of the rest of GWR steam. The Knights also received the Swindon de Glehn bogies for the first time in the class.

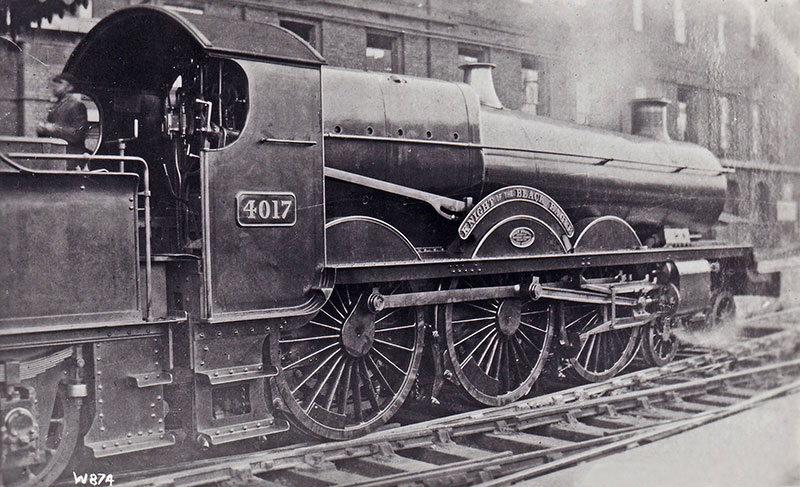

No 4017 Knight of the Black Eagle, built in April 1908, was renamed Knight of Liège in 1914. The locomotive was withdrawn in November 1949

Nos. 4021 to 4030 were named after Kings and they were the first instance of the fluted inside valve case that was last fitted to the first batch of Castles that includes our very own No. 4079 Pendennis Castle. There were Queens followed by Princes and Princesses. This lead all the way up to No 4060. The last twelve were all built under Collett between 1922 and 1923. These became the Abbeys. The developments shown in the Stars were truly remarkable. The previous Saint class had service intervals of between 70 to 80 thousand miles. The Stars were clocking up between 125 to 150 thousand…

No 4025 was originally named King Charles, when built in July 1909, then became Italian Monarch in October 1927. The name was removed in 1940. The locomotive remained nameless until withdrawn in August 1950. This photograph was taken by Ben Brooksbank on 28 December 1948

The engines saw a few renaming sessions. No 4017 Knight of the Black Eagle was renamed after the start of hostilities in 1914 as this referred to a German order of chivalry. Still, we won’t make that mistake again, right? Well… When the No 6000 or King class was built, the ‘Star Kings’ were renamed. They included Belgian Monarch, Italian Monarch, Japanese Monarch and Romanian Monarch. Then a certain thing started in 1939. All had their nameplates removed and the words ‘STAR CLASS’ painted on the centre wheel splasher. No 4021 was called British Monarch and so fared a little better.

No 4039 Queen Matilda was built in February 1911, and withdrawn in November 1950

These engines were excellent performers and were highly suited to their tasks. The advent of the Castle and later King classes meant that they were displaced from the majority of the front line services, being more usually used on secondary services. In this role they also performed admirably. The fundamental ubiquity of their designs meant that it was possible to rebuild the Stars into Castles. This often happened when the cylinder blocks on the Stars became life expired. 15 were rebuilt including No 4000 North Star.

No 4058 Princess Augusta was built in July 1914, and withdrawn in April 1951

The first of the class not rebuilt into Castles were withdrawn as early as the 1930s but the last went on until 1957. The design of the Star is a genuine milestone. It was a huge leap forward in itself but it also sired the Castle and King classes too. It is fitting therefore that No 4003 Lode Star is preserved as part of the National Collection. She clocked up over 2,000,000 miles in service and stands as a reminder of those early pioneering days that provided so much potential. Next time we’ll take a look at the start of the Castles.

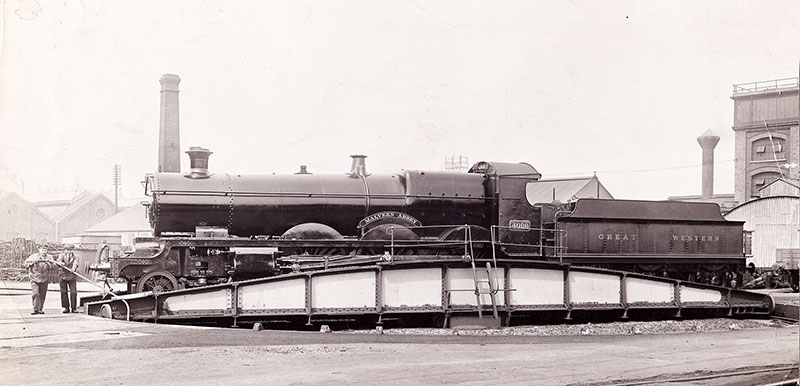

No 4066 Malvern Abbey was built in December 1922. The locomotive was rebuilt as a Castle, No 5086, in December 1937 with the name Viscount Horne after the Chairman of the GWR, and withdrawn in November 1958

*Latin - it means “Through adversity to the stars” and happens to be to motto of the Royal Air Force.

**A method of reusing the heat from the fire a second time to make large engines more efficient. We’ll take a look sometime…

FRIDAY 3 FEBRUARY

100 Years and 4 Castles, Part 1 - The North on the West

Excited?

Me?

YES!

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the first Castle class locomotive being completed (No 4073 Caerphilly Castle), we are going to get no less than four of them in one place. Twice. In conjunction with Vintage Trains at Tyseley, No 5043 Earl of Mount Edgcumbe and No 7029 Clun Castle will be visiting Didcot for a few hours on Saturday 4 March 2023 and will be lined up outside the shed with No 5051 Drysllwyn Castle and No 4079 Pendennis Castle. We will repay the favour by loaning No 4079 to Tyseley for an event in Birmingham later in the year where No 5080 Defiant will replace No. 5051.

In order to work up to this and No. 4079’s little tour prior to spending the summer season at Didcot, we really ought to look at how we got to this point. A history that began at the start of the 20th century.

No pressure then…

We all know that, as most things on the Great Western in the twentieth century did, it starts with George Jackson Churchward. The 1900s were a time of intense experimentation for Swindon under Churchward. The whole process was pushed forward in the sole aim of producing the best locomotives possible for the Great Western Railway. His Saint class 4-6-0 was already a masterpiece. But there was one more trick up their sleeves.

They had bought three de Glehn compound locomotives to see whether it was worth using that technology in the GWR*. The shorter distances in the UK meant that the extra maintenance costs and complexity didn’t stack up against the savings in fuel consumption. What did make sense, however, was the layout of the cylinders on these engines.

To go fast, you need large amounts of power. For large amounts of power, you need a large piston area. You could have two large pistons. The issue is that these will be quite big and they will literally swing the front end of the engine from side to side. What you do is to take the same piston area and share it over more pistons. The de Glehn machines had two inside cylinders between the frames. These drove the front driving wheels. There were then two outside cylinders and these drove the rear set of driving wheels. It’s the same idea as a V8 engine in a car. It gives you big power but with balanced movements in the pistons, even at high speed. As one goes one way, the other one of the pair goes the other.

No 40 as built with 4-4-2 wheel arrangement and without name

The combination of a four-cylinder design and the Swindon No 1 boiler would all come together in April 1906 when, under lot No 161, a prototype was produced. It was built in the same manner as the Saints that were put up against the de Glehn 4-4-2s. They were intended to be 4-6-0s but were built as 4-4-2s to provide a fair comparison to the French engines but were also easily convertible to their final 4-6-0 form. The Walschaerts valve gear on the French machines was fitted to the outside of the engines but the GWR tradition was to fit it inside the frames**. The valve gear that they used on this new engine was of a strange ‘scissors’ variation of Walschaerts. The idea here was to not use eccentrics but it wasn’t copied later on. The de Glehn influence was also to be seen in the front bogie – as we have seen before in Going Loco.

This engine was originally numbered No 40 and in was named North Star not long afterwards. This was an important name for the company. One of the earliest truly successful broad gauge engines was named North Star. The long history of the company meant that it was keen on its traditions and the chance to reuse this on their railway was not to be ignored. The engine was converted to a 4-6-0 in 1909 and renumbered to No 4000 in 1912.

North Star rebuilt as a Castle, at Shrewsbury in the 1930s

The reason for the renumbering was that she was the prototype for a whole class of four-cylinder 4-6-0 express passenger engines. They too were named after the ancient Star class engines but that is the next chapter of the story for next week. They were all numbered from 4001 onwards but as the class doyenne, North Star got the three zeros! No 4000 was a particularly long lived machine. She was converted to become a Castle class engine in 1929 and lasted in that form until May 1957. Not bad for a prototype that was built to just prove a point! While she is long since gone, the echoes that this engine started continue to be heard even today. Especially when one of the surviving GWR Castles opens her regulator…

*These engines were looked at in Going Loco in December 2022.

**No matter how difficult it is to maintain!

|

|

|

|

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.