Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - March 2023 - Going Loco - March 2023

Going Loco - March 2023

FRIDAY 31 MARCH

Didcot’s Rarest Railway?

We have quite the tradition here at Going Loco for having a silly or unusual subject for the April Fool’s Day season and this year is no exception! This week’s topic links in rather neatly to the upcoming Victorian Weekend too… I have enlisted the help of none other than Didcot’s favourite shopkeeper, Mr Thomas Macey. Thomas is not only passionate about all things Great Western (don’t get him started on Lady of Legend – he’s as bad on that as I am about Pendennis Castle!) but he has another very deep interest in the history and artefacts surrounding retail. What on Earth has that to do with railways? Read on dear reader, read on…

“I am a draper mad with love, I have come to take you away to my emporium on the hill, where the change hums on wires.”

So Mr Mog Edwards declares in Dylan Thomas’s ‘Under Milk Wood’.

What is this all about, I hear you cry?!

Sit back, pour out a cup of tea and join me in the exciting world of……cash railways!

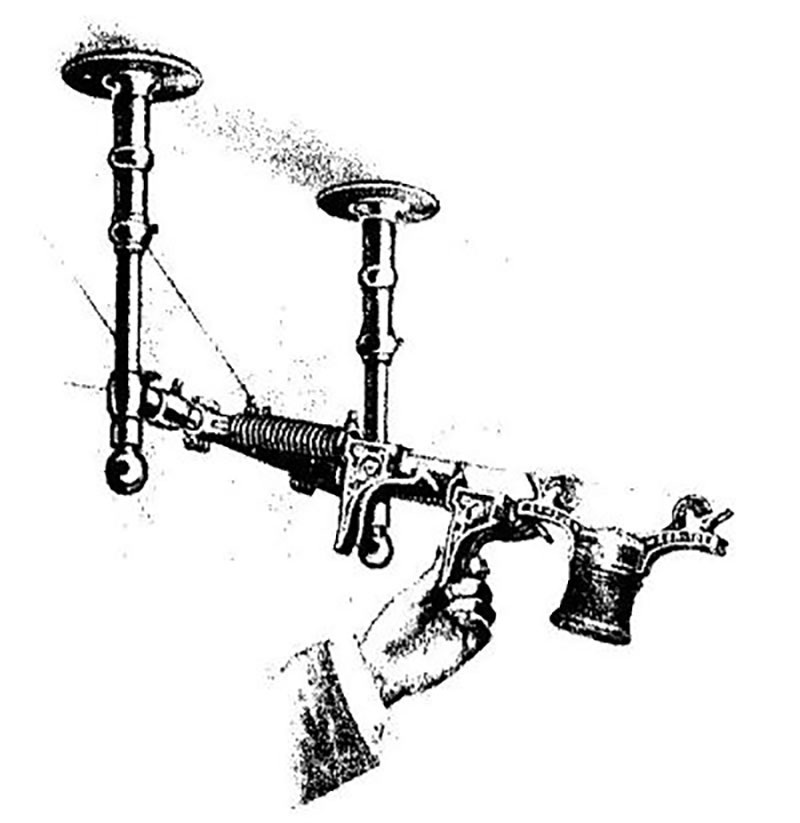

A drawing of a cash terminal from a Lamson catalogue dated 1912

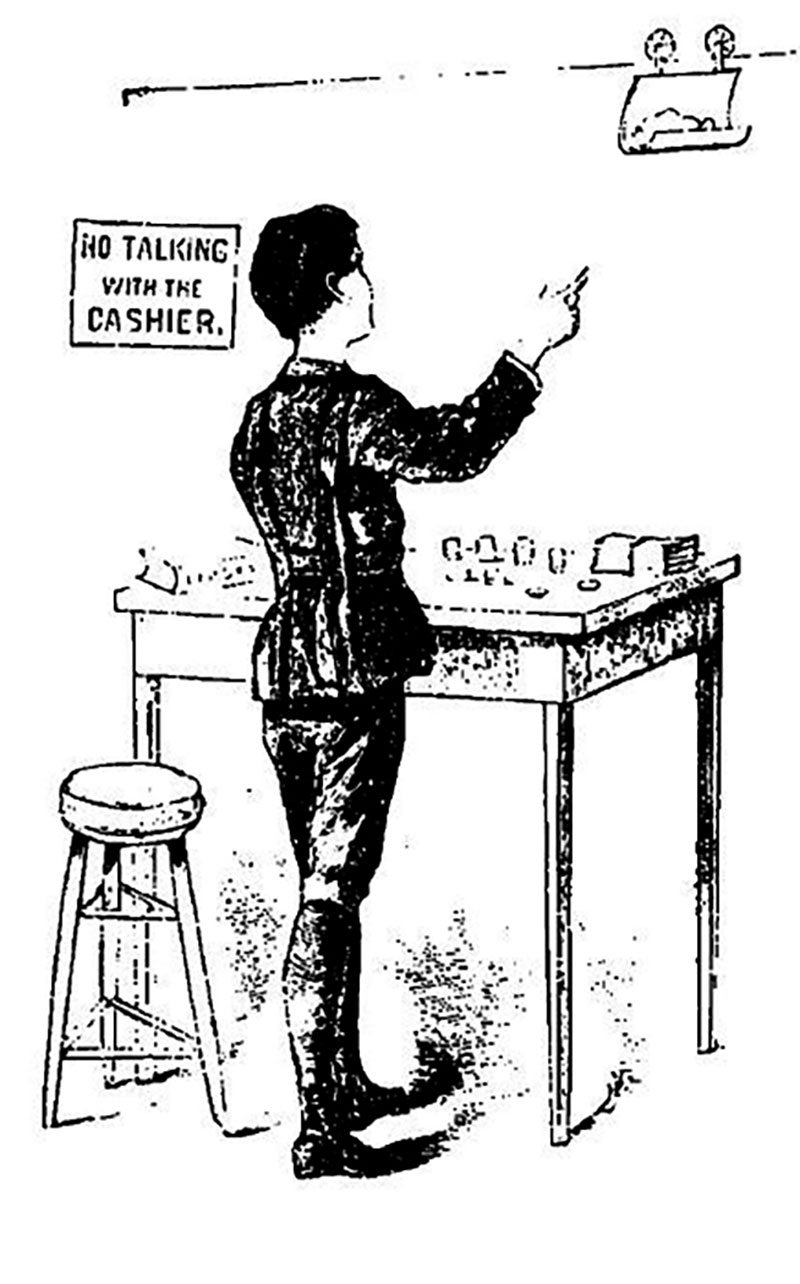

Yes, there was a time when, having chosen the items you wanted to buy, you would hand the smartly-dressed sales assistant your payment, and it would be whisked away to the cash office for your change. In the good old days of retail, when we were a proud nation of shop keepers, the sales assistant would serve you personally, from the moment you stepped into the shop, right up until they handed over your goods wrapped in brown paper. Naturally, having all your staff engaged in serving meant that tills were often left unsupervised, and this led to theft.

Shop mangers don’t like it when money is stolen (they don’t like discounts and refunds either, but I will not go into that right now) and so they sought ways of keeping their hard-earned cash safe. A few retailers employed children, who were known as ‘cash boys’. The sales assistant would shout out ‘CASH’ and the child would collect the payment and take it to the cashier. However, it was often commented on the poor living conditions and pay these children received.

Then one bright sunny day (it might have been raining, I don’t know)… a young chap by the name of William Stickney Lamson came up with a fantastic idea!

Why not place the money in a hollow wooden ball that rolled along tracks on the ceiling to take the money safely and quickly to the cashier. Why, without knowing it, Lamson had created the world’s largest marble run. But even more incredible, other retailers heard of the idea and wanted one for their shop… Lamson set up a factory to manufacture his wonderful new idea and orders flooded in.

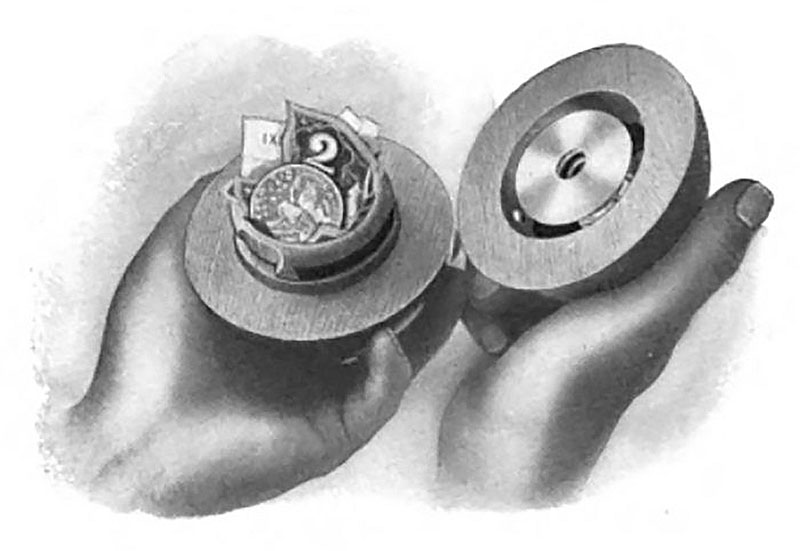

An open cash ball, showing how the money and receipt are held in place

You could say…the money just rolled in………sorry…I won’t do that again.

But Lamson had come up with a business idea that made him very wealthy, and before long he was opening outlets around the world, including a factory in London. And it wasn’t just cash balls, Lamson also manufactured wire systems where the carrier was suspended from a wire track on a wheeled carrier, and pneumatic tube systems that propelled the cash in brass carriers at unbelievable speeds through a network of metal tubes.

Lamson offered two services to customers. If you rented the system they would send a ‘linesman’ who would install the cash railway and maintain it for you for a fee. If, however you purchased the system outright, Lamson suggested you ‘consult your local bicycle maker who would have the necessary skills to install it for you’.

Some retailers were so proud to have the latest retail technology that they even declared it in the local newspapers! There were even toy cash railways for children, sold by many of the well-known London toy shops.

‘The Young Storekeeper outfit’, a child’s cash railway from 1889

And before long other manufacturers came on the scene marketing their own improved cash railways…. truly it was an age to be a shop keeper.

But…and there is always a but in these stories, retailing changed. Tills became much safer, personal service was scrapped in favour of impersonal self-service stores and even carrying cash in recent years after Covid19 has fallen for quick and easy card payments. The golden age of the cash railway was over, and one by one they were scrapped. Once there were thousands of cash railways in use all over the world…now only a handful survive. Those shops that did carry on using a cash railway were forced to make do and mend when replacing parts, sometimes substituting clothes lines for the wire track.

If you have got this far, well done… the climax of my tale is just a pneumatic carrier away...

The Lamson ‘Cash and Parcel’ railway as sold on ebay in 2020

Back in 2020, whilst searching ebay, I came across a Lamson cash railway, rusting away in a box. As a collector of cash railways (yes, we do exist!) I clicked the buy-it-now so fast my laptop has never quite recovered. What I had managed to buy was one of the rarest cash railways now in existence. Known as a ‘Cash and Parcel’ railway, the shop assistant would send both the customer payment and the purchased goods in an overhead basket along a wire track. It was sent to the cashier who would deal with the payment and wrap the goods, before returning it back to the shop floor. Manufactured by the ‘Lamson Cash Carrier company’, (Wouldn’t William Stickney be proud) in 1905, it was originally installed in a shop in Kansas City, USA.

Having provided that shop with many years of loyal service, it was removed as technology changed and left to rust. I had it sent over to the UK and delivered to Didcot where, with the help of my friends here, it has been fully restored and installed in our gift shop as a working exhibit. And its claim to fame?

It is one of only eight ‘Cash and Parcel’ railways known to exist worldwide.

The only example of a ‘Cash and Parcel’ Railway in the UK.

The only working original cash railway in the south of England.

The fully restored Lamson ‘Cash and Parcel’ railway at Didcot Railway Centre

Didcot Railway Centre is known for its world-famous collection relating to the Great Western Railway, now it can add a cash railway to the list!

And the technology hasn’t completely gone. Pneumatic tubes, once commonplace in large department stores are still used in some supermarkets to clear tills, hospitals to transport samples to research labs and even some restaurants. I can proudly state that I am one of the very last people to use an original Lamson cash railway, having worked for one of the country’s oldest family-owned department stores.

The last fully working original pneumatic cash railway at the former Jackson’s department store in Reading

They bring back many happy memories for those who were taken shopping with their parents and watched with wonder as their money was sent above their heads at high speed along metal tracks.

Just like steam locomotives, they have a distinctive sound with metal wheels running along wire tracks and a carrier being propelled along tubes with the rush of air.

Do you have memories of visiting shops with a cash railway?

Thanks Thomas! This is another example of how the preservation movement at Didcot has enabled the preservation of a wider group of objects and gives them an excellent showcase to remain operational and entertain the public. Thomas also has a great deal of equipment pertaining to the vacuum tube system too. Perhaps this too may one day find an operational home at Didcot? I do hope so! It all goes back to what we should be doing at Didcot. To enable people to travel back in time and give them experiences that are not now easily obtained in ‘the real world’. I’d say that the cash railway definitely fits into this bracket. Long may we continue to hear the trundling of little wheels along wires while purchasing our goods!

If you haven’t booked your tickets for the Victorian weekend, please book now.

FRIDAY 24 MARCH

SERIOUSLY Old School!

Looking forward to our next event, we have the Victorian Weekend coming up over Easter on 7 to 10 April, and looks like it will be absolutely cracking! No less than the great, great grandson of Charles Dickens, Gerald Dickens, will be making appearances throughout the weekend. Our friends in the office, Sarah and Thomas have been busy with Hook Norton Brewery and have devised a special Didcot Railway Centre Beer call ‘Off the Rails’. Let's hope that's not a portent… For railway nerd purposes, and let’s face it – that’s why I’m writing this(!), we have a special guest.

Why not book a visit to Didcot this Easter?

Gerald Dickens on a visit to Didcot

We get to have a go with the oldest working standard gauge locomotive in the UK – Furness Railway No 20. So where did this ancient engine come from? The Furness Railway (FR) came out of a scheme devised in the 1840s to link Ulverston to iron ore mines in Dalton-in-Furness, slate mines in Kirkby-in-Furness and the coast at Barrow Harbour. The idea was: ‘to improve the present very dilatory provision for the transport of the valuable Mineral products of Furness and adjoining Districts to the Coast’ although it eventually had a fairly extensive system in the area.

Sarah and Thomas brewing our beer at Hook Norton

The railway expanded quickly and it was keen to buy the latest hardware. At this time Sharp, Stewart and Co were offering a wholly suitable 0-4-0 tender locomotive. This was duly snapped up by the FR as four were initially ordered. The order – No 440 on Sharp Stewart’s books – went in on 23 December 1862. A nice little Christmas present for the order books it would seem! The last of these locomotives was works number 1448, completed in 1863, which was to become Furness Railway No 20 in service. They were obviously pleased with the machines and the order was eventually doubled to eight units.

No 20 as she is now restored and will appear at Didcot

Whilst the engines were more than adequate as built, the huge growth in traffic on the railways in general and the FR in particular meant that they became obsolete very fast. The smaller, lighter tender engines simply weren’t up to the task of pulling the heavier and heavier trains that were the result of the inexorable march of progress. This led to the first four being sold into industry. FR Nos 17 to 20 were bought by the Barrow Hematite Steel Co in 1870. Two more, Nos 25 and 26, followed in 1873. The last two, Nos 27 and 28, continued to work on the FR until they were withdrawn in 1918.

The engines that went to the steelworks had a short stay-over in their original manufacturer’s works. Here they were converted from tender locomotives to become saddle tank engines. The possible reasons for this could include making sure that as much weight as possible was available to sit over the driving wheels and improve the pulling power of these diminutive machines. It clearly worked – they were almost new when returned to their maker and this was a very effective way of making them relevant and useful once again. The engines were all renumbered and No 20 became No 7.

And that really was that.

They just kept working.

And working…

And working…

The records show that No 7 was returned to the works again in 1915 to receive a new boiler and she was so valued that as late as the 1950s, she got a new set of driving wheels. These engines served their masters in the steel works for nine decades until diesels finally displaced them in the 1960s. The years of service were so impressive and they had become such a part of the local landscape that the last two (Nos 7 and 17) were gifted to local schools. No 7 went to the grounds of the George Hastwell Special School in Abbey Road, Barrow and No 17 went to Stonecross School in Ulverston. It was from here that the unique nature of the engines was realised. In 1983, No 7 was purchased to be preserved and went to the Steamtown museum in Carnforth, Lancashire. The engine was dismantled to begin restoration but the sudden death of one of its owners caused the restoration to stall.

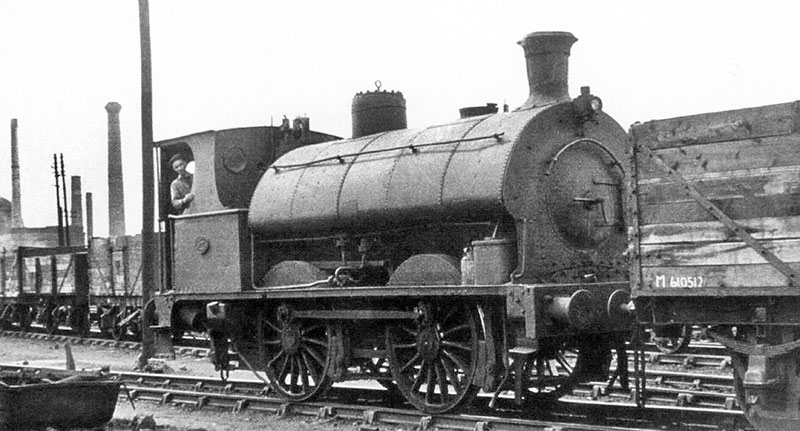

As No 20 would have appeared when working as a saddle tank at the steelworks in the 1950s. Photo published in The Mail, Barrow-in-Furness

The Furness Railway Trust stepped in at this point to secure the engine for future generations in 1990 and, from there, an ambitious plan was drawn up. On the 150th anniversary of the first passenger train being used on the original FR, the Trust set out its scheme to return No 7 to its original condition as FR No. 20. This was no small task, she needed a new boiler as well as a whole host of other parts – not least of which included a tender. They set to raising funds and a whole host of organisations donated to the cause including the Heritage Lottery Fund, the PRISM Fund of the Science Museum, The Idlewild Trust, Furness Building Society and Cumbria County Council. The total cost was at the time £140,000.

The money wasn’t the only issue – the information about the original condition of these engines was scant. A full historical investigation was the result that spanned the world! The usual sources of the National Railway Museum archives and private collections throughout the UK were the first port of call but there was even a bit of help coming from as far away as Turkey. Here, an original Sharp Stewart tender of the correct vintage was discovered. This was duly measured and photographed to add puzzle pieces to the overall picture. Eventually a full set of working drawings were produced. Now all they had to do(!) was use them…

The rebuild of No 20 was undertaken by a few different contractors. The new tender chassis was undertaken by Marconi Marine (VSEL). The construction of a new boiler was undertaken by Israel Newton. This was traditionally built using riveted construction. The new tender superstructure became an excellent project for staff and students at Furness College. The shipyard also offered the facilities for the Furness Railway Trust to perform the rest of the overhaul. The engine finally steamed again on 13 January 1999 and has been a firm favourite in preservation ever since.

No 20 on the Bo'ness & Kinneil Railway hauling two vintage Caledonian Railway carriages. Photo by Greg Fitchett, Creative Commons

The even-better news is that the other survivor – BHS Co No 17 / FR No 25 has been donated to the Furness Railway Trust! They intend to eventually rebuild her to operational condition but in the later rebuilt saddle tank form to give a complete picture of the life and times of these remarkable survivors.

What is also very exciting is that No 20 will be operating during the Victorian weekend alongside No 1340 Trojan. Trojan is of 1897 vintage – a spring chicken compared to No 20, but still the oldest operational GWR steam locomotive at the moment – 126 years old at the time of writing! Add to this the 163 years of No 20 and that’s a total history of 289 years. And they are both still running. It’s quite remarkable and a chance to get up close to No 20 in operation, in a way not normally available.

Don’t miss it!

PS The Furness Railway Trust have a book on No 20 called The Great Survivor. To purchase a copy click on the link.

FRIDAY 17 MARCH

100 Years and 4 Castles, Part 7 - Our Guest Speaks!

Last one on the Castles for now, I promise but I couldn’t let the opportunity to:

- Let our guest for the day have a chat with you, and

- Have a week off from writing Going Loco.

So, I’m sure that Lawrie Rose needs no introduction. If he does, he’s written his own, so over to him!

Lawrie and Pendennis Castle at some unholy hour in the morning!

Hello Everyone and Welcome to Lawrie’s Going Loco. Now, for those of you who recognise that greeting – there may well have been a slight laugh, or at least a smile, for the rest of you who are looking at your screen feeling just a tad confused, allow me to introduce myself. I’m the guest editor of Going Loco. My name is Lawrie, and I run a YouTube Channel called Lawrie’s Mechanical Marvels – https://www.youtube.com/c/LawriesMechanicalMarvels

We focus on vehicular heritage and getting involved with it – everything from tractors to trains. Our most popular series is Lawrie Goes Loco, where I travel around the country to take locomotives out for a drive, looking into their history, what I like about them, and most importantly, how to prep and drive them.

As part of this, I recently came down and did some filming at Didcot, taking out ‘The Rat’ and having a go on the Traverser (videos coming at some point), where I started talking with volunteers down here about the (then) upcoming Four Castles event.

As luck would have it, I bumped into Drew, who had led the project that was the giant 3D Jigsaw puzzle, otherwise known as Pendennis Castle, and one thing led to another, and soon an email appeared in my inbox with a plan. To film the event, from the footplate.

Lawrie Rose and his Lawrie’s Mechanical Marvels Team, Charles Brewster and Dan (Larry) Sellwood

This wasn’t the kind of email to turn down, and I rather excitedly agreed. I live just over three hours from Didcot, so I came down the night before, and was treated to an evening tour around the Engine Shed, talking stories of the mighty Iron Dinosaurs that slept before us.

To those of you who have never sampled the atmosphere of the Shed at night, there is nothing else like it. The only time I have felt the same emotions, that sense of timelessness, was when I was out in Poland, standing in the Shed at Wolsztyn, the last working standard gauge depot in Europe. The still of the evening, with these sleeping engines is almost enough to move one to tears. That sense that you can believe, just for a fleeting moment, that I’m a young boy, looking round a real, working, proper Shed, that childhood sense of untainted wonder almost overflowing.

A real Shed. Doing just what it was meant to do – housing engines just resting before their next duty. That sense of magic completed by the fact it’s just right. Great Western Engines, sat in a Great Western Shed. That magic is unlike anything else that you can sample when the public are there, with the noise and busyness of people. In that still moment, you can almost hear the whispers of glories past, this one last stronghold of the past, this actual working time machine.

There are many moments in doing this job, that I feel really very privileged to be able to do what I do, and the opportunities that it presents, and this was one of those moments, to just breathe it all in. And then, to go to bed, and try and get some sleep. For we were up early. For those of you who don’t know, waking a steam engine isn’t a fast process, and in fact, it started before I arrived. Pendennis Castle was drawn outside, and a warming fire lit inside her cavernous firebox.

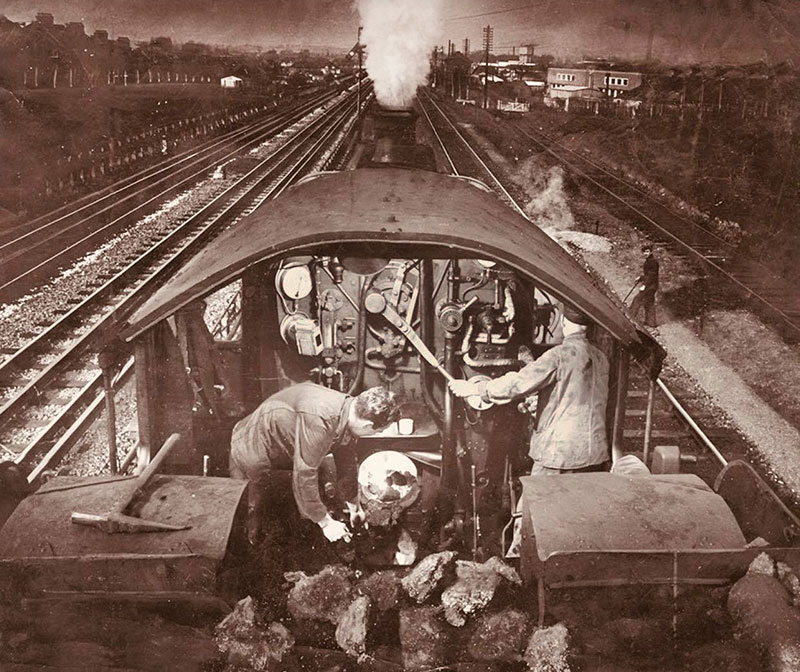

Whilst not as wide as the fireboxes on Bulleid’s Pacifics, or Peppercorn’s A1s, it’s still an impressive 11 feet long. Which, as the last thing I fired was an 0-4-0 RSH at the Whitwell and Reepham Railway, this was quite an evolution – but we’ll get onto that.

The warming fire, as the name suggests, is to begin warming the locomotive. We do this to combat thermal shock – metal does not enjoy going from cold to hot in a short space of time so to ease the fatigue we try to do it as slowly as possible. Getting a fire in the day before is one of the best ways to do this, getting some warmth through the machine. The firelighter signs on at 5 am. Which means that you need to be awake, dressed and ready before 5. Which is far too early.

One thing that people may not appreciate is that filming is a very slow process. Working on what you actually want to show the viewer, and trying to make it happen makes any task at a bare minimum, three times longer. Trying our best not to hamper progress I set about doing the pre-light up checks, making sure there was water in the gauge, the regulator was closed, the reverser in mid gear, cylinder drains open, and the handbrake on. Then repeating the process for the camera, and getting the additional shots I needed to pull my edit together.

Even piling wood into the firebox had to have the process repeated to capture the moment. Eventually though, we were ready to light my fire, and begin the process of bringing Pendennis round. It was at this moment that two notable things happened. Firstly, I broke my chaperone’s lighter. So we had to use the spare, one of my crew had brought along, in case of such a happening.

Secondly, I was hit with the enormity of what I was doing. Pendennis is one of those engines that I knew of growing up. I knew she had been shipped off to Australia. I knew of her fame, of the remarkable amount of miles that she had under her belt. (some say to the Moon and back… FOUR times) The fact she flew the flag for the UK in a land down under. But this legend I had never actually seen. Not in person.

The first time I laid my own eyes upon her was now. And I was on the footplate, about to wake her from her slumber. An engine only recently returned to steam, for the first time this millennium. I mentioned sometimes I really am amazed at what I get to do, and this was one of those moments. Thinking of everyone who had thrown the match in before me, from the glory days of the GWR, to BR, the crew in Oz, to those who crewed it under Sir William’s ownership, the man who I purchased my locomotive from, there was a real sense of gravity to this moment. Also the match was beginning to burn my fingers.

Once I’d thrown some paraffin-soaked rags into the fire and was feeling somewhat confident that the fire wouldn’t go out, I could soak in the moment and just enjoy being on the footplate, the smell, and the crackle of the fire. It was really too dark to be able to film, and so we basked in the moment, listening to the old girl as she came round, eager to hear what stories she might tell.

As the light began to rise I managed to summon the energy to put some of my emotions into words and a little bit of the history of the engine for a piece to camera. I am very much hoping to be able to return at some point and do a proper episode on the locomotive – but this was just a taster. And besides, as wonderful as Pendennis is, she wasn’t the sole attraction.

The loco awakes!

My next task was to help with the oiling up, which once again when filming, takes much longer than one would expect. By the time we’d done the coupling and connecting rods for camera, the others had completed the entirety of the other side, the bogie, and had started inside the frames. One thing my followers enjoy is seeing me struggle inside the frames of a locomotive, and as Pendennis wasn’t sat over a pit, we all agreed I should go inside to oil up the eccentrics and the big ends of the internal motion.

I do not share the build of a ballerina. And Christmas, with all its gluttony, has not been kind to me, nor does spending most of my time sat in front of a computer editing and running a YouTube channel, so believe me when I say that I really, really struggled to fit myself between the driving wheels and inside the frames. I also made a mental note to cut the footage down to make myself appear somewhat more competent.

However, there is something special about actually getting up close and personal with the inside motion, something that so few people actually get to see and appreciate. Something so elegant, hidden away. Something so very difficult to actually get to and oil up. Getting in was one thing, getting Charles, my cameraman somewhere where he could actually see me to film, that was another challenge entirely.

An unusual sight for most people - a quiet Didcot running shed. The two ‘Iron Warhorses’ Nos 5322 and 3822 in attendance

Which again, rather slowed the whole process down, but eventually, we were done, and I managed to escape to the outside world again. I had done so very little in the grand scheme of oiling and preparation, and it was in truth, perhaps a token effort for the camera, something that the actual crew could have accomplished in half the time, but I felt a huge sense of pride for actually doing it. For actually helping. The little boy who lives inside me was beside himself with excitement. I helped oil up an engine that I read about, I heard stories about as a boy. This was special.

Apart from throwing the odd round onto the fire, there wasn’t much else to do now but wait, and listen to Pendennis as she woke and started to show her excitement for seeing two of her sisters for the first time since, at the very latest, the seventies. In truth, I don’t know the last time when Earl of Mount Edgcumbe, Clun Castle, and Drysllwyn all sat on Shed together. I do know that it certainly hasn’t happened in my lifetime, and that it’s been an exceptionally long time since this happened.

And this gathering was special. And I, like Pendennis, was very excited. Whilst I sat listening to stories from the crew, I suddenly became aware that Didcot had gone from empty to full of excited enthusiasts, ready to experience the moment of the four Castles together.

Time has flown past, we had steam, Pendennis lived, and the main line excursion has arrived. Once it had shunted its train came a moment that I never thought I would see. From the footplate of a Castle, next to a Castle, in the shadow of a Great Western coaling stage, on Shed, in front of a Great Western Shed, two mainline Castles, their first duty done, reversed onto Shed. Like in the days of old, when finished for the day. They came back. A Castle, coming on Shed. Next to a Castle in Steam. Next to a Castle.

THAT line up. Again. Doesn’t get old does it?!

It sounds silly to write it, but honestly, thinking of that moment, the magic, and how impossible it should be in this modern world, and to be part of it in a tiny way, makes me tear up. I don’t think I have the sufficient grasp of the English language to be able to sufficiently express to you dear reader, quite the feeling of being there. The word legendary is certainly overused in today’s world, like when your mate brings a couple of packets of crisps as they bring over the drinks in the pub, but I think I’ll reclaim it here. This was indeed an absolutely legendary moment. Something that I will never forget.

Once the engines were stabled and safe, I did a short bit of filming, and then headed out to get just one photo for myself of the four together. This was meant to be a short trip, and then to return to the footplate. However, I got to meet a load of the lovely people who enjoy my channel, and my short trip away ended up not being as short. In fact, every time during the day that I departed from the footplate I got to meet more and more of the people who enjoy my content. This is a hugely rewarding experience. This was a very, very good day.

Lawrie, Charles and Dan with your usual blogger, Drew Fermor, on the footplate

Moving to the turntable and watching it actually do its purpose, not for show, to actually turn locomotives for their return leg, from the footplate, was again just superb, for at that moment Didcot was not a museum. It was alive. That last ember of a Great Western Shed flickered into flame again. This site had real, mainline engines on it. Being turned. Being serviced ready to head out onto the mainline. Just like they would have done in the days of the GWR. Back in the days of BR.

This my friends, this was special. And to see it from one of their sisters. An engine as capable, I could almost kid myself that we would follow them out to the main, to collect our train and head out. This was as close as I’ll get in this country to going back in time.

Castle, Castle and Kerosene Castle?

After the pair departed, and the public mostly dispersed, Pendennis was allowed to replace 4144 and take a few trips up and down the demonstration line. Under the careful gaze of Drew, I was given the shovel, and told to get on with it. It’s been a while since I had worked a large engine, and after a couple of misplaced shovels, I found the knack again, and enjoyed hearing coal bouncing off the tube plate. A hugely rewarding sound. To just fire this machine, to be able to say I have done that. I got to do it, and that I didn’t muck it up, I was pretty sure was one of the best feelings in the world. Turns out, I was wrong.

As it happens, the best feeling is to be given the regulator. To feel all that power of a thoroughbred. All that history, all those stories. To drive Pendennis. It was a fairly emotionally charged day, full of things that likely I’ll never get to see or do again, of experiences that I cannot fully commit to print. But this.

Yeah. This was something else. My only real problem was I wanted to go further, with a bigger train, and see what she’s made of. This was something of a tease, to see all that potential and not be able to harness it. This was intoxicating.

Apart from offering to ash out at the end of the day – something that I only thought was fair, this marked the end of my day at Didcot.

I can only extend my gratitude to the DRC, to everyone who helped make my visit possible, for their hospitality, and of course to everyone involved in the restoration of Pendennis Castle. You have done an outstanding job. It was one of those days that I woke up the next day, wondering if I’d dreamt it all, as it just didn’t seem possible that I could have been involved.

From the bottom of my heart to you all, thank you. If you’re still reading this, to you my dear reader I extend my thanks, and if you haven’t already, perhaps have a look at the video I shot, and let me know in the comments what you think: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ewBD9KPT5v8

And in typical YouTube style, don’t forget to like and subscribe, and perhaps I’ll see you in these pages again. Lawrie.

Cheers Lawrie! During his visit, Lawrie started looking round the shed and eyed up a number of the running fleet so I’m sure we will arrange many a return visit! Until next time good sir, until next time…

FRIDAY 10 MARCH

100 Years and 4 Castles, Part 6 - The Visitors…

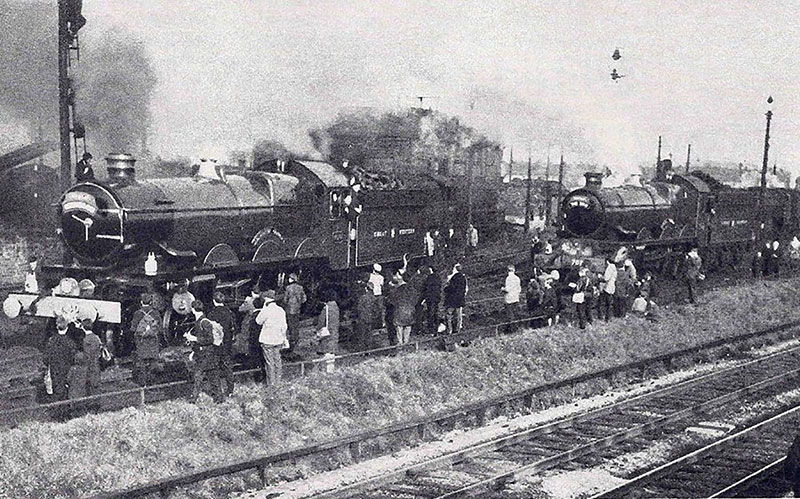

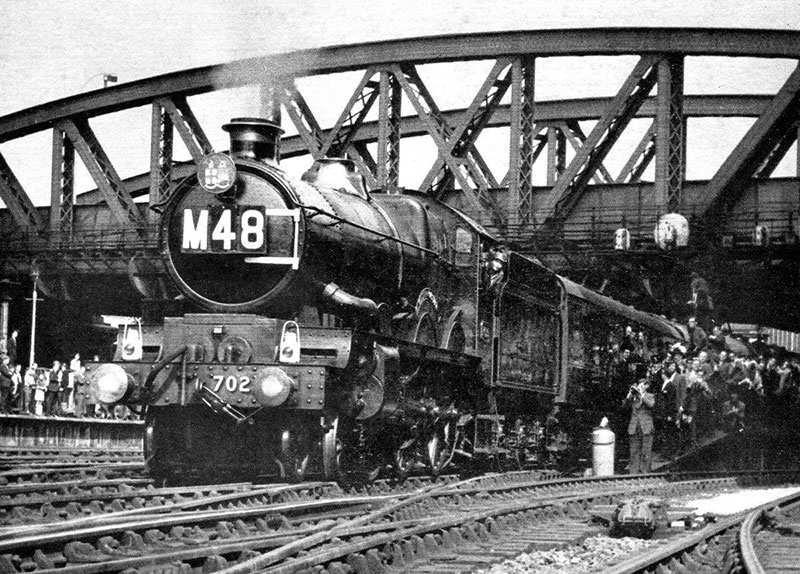

7029 and 5043 steaming through Didcot station on 4 March 2023

Well, that was fun! Ok, my rather privileged position of No 4079’s fireman afforded me quite the view but if the reaction on the day and on social media has been anything to go by, such a position wasn’t needed to have had a great time seeing the four Castles gather for the first time in this centenary year for the Castle class. It struck me that we really should take a little look at the two locomotives that made the event possible – No 5043 Earl of Mount Edgcumbe and No 7029 Clun Castle. They both have a unique tale to tell…

No 7029 Clun Castle

7029 Hauling the northbound Devonian through Dawlish on 2 July 1955. Photo by Ben Brooksbank

In the same way that No. 4079 Pendennis Castle is the representative of the first of the breed, No 7029 sits as the polar opposite. This is nearly the last of the breed. No 4079 is Castle number 7 of 171, and No 7029 is Castle number 163 of 171! She isn’t a Great Western Railway locomotive – being built to a GWR design by British Railways in May 1950, the last year and the last batch of Castle production. She was initially allocated to Newton Abbot shed and was reallocated to Plymouth Laira in 1956 and from there to Newton Abbot in 1957.

In 1959, she gained what I described last week as the ‘GTI’ upgrade and received a four-row superheater in place of her original three-row version. To help her steam on the increasingly poor coal available at the time, she also received a double chimney. She served faithfully, becoming a Paddington engine at Old Oak Common shed in 1962. The engine has several claims to fame in her service career. The first being that she was one of the Castles (No 4079 included), that took part in the special service in May 1964 to celebrate the 60th Anniversary of the 100mph run of No 3440 City of Truro.

7029 departing from Paddington on 11 June 1965

After moving to Gloucester Horton Road in 1964, No 7029 took part in the final swansong of the class by pulling the very last service train by a Castle from Paddington to Banbury on 11 June 1965. The engine herself hung on until she was finally withdrawn by BR in December of the same year, making her the last of the kind to come out of service. She faced an uncertain future until salvation appeared in the form of Patrick Whitehouse – one of British railway preservation’s pioneers. He bought the locomotive for her scrap value £2,400. She then went to live at Tyseley – where she still lives to this day!

In preservation, she has continued to make historic runs. She, again with No 4079, pulled the last trains on the GWR’s northern route to Birkenhead. She also pulled the last train that ran from Birmingham’s Moor Street station. She ran on the main line until 1988 and then spent a while out of ticket. She returned to traffic in February 2019 and has regained her position as one of the greats of steam preservation.

4079 and 7029 being serviced at Chester with the last trains on the GWR route from Paddington to Birkenhead, on 4 March 1967

No 5043 Earl of Mount Edgcumbe

5043 with a northbound railtour approaching Culham on 20 October 2011

While No 7029 has always been a star, No 5043 was, for a long time, just another Castle. She is much older than Clun, being built in 1936 by the GWR. She was originally named Barbury Castle but was renamed in September 1937 to become the first of the ‘Earls’. She was at this time at Old Oak Common and remained there until the Second World War. For a brief period she was at Swindon but again returned to Old Oak until the early 1950s. She also received the double chimney and four row upgrade in 1958, one of 65 to be so treated. This pair of engines are the only ones in preservation to sport this.

The engine found herself in Wales when she was withdrawn in 1963, this meant she was positioned in the perfect place to end up at the ‘Old Engines’ Seaside Retirement Home’ that is otherwise known as Barry Scrapyard. This lifeboat enabled her survival and she came to the attention of the team at Tyseley. Unlike No 7029 however, No 5043 was bought initially as a source of spares for her more modern sister. As such she was removed from Barry in 1977. When at Tyseley, she was stripped of many of her components and that’s where she stood. Until 1996 that is, when the project to restore her to working order in her own right was announced.

5043 approaching Didcot with the Cheltenham Flyer railtour on 11 May 2013

The long process of bringing her back to full health commenced in 1998 with removal of the boiler. She moved under her own power for the first time in several decades on 3 October 2008. She has gone on to become a star of the main line steam circuit. Her performance on the climb to Ais Gill summit in October 2010 saw her set a record for a Castle that is yet to be equalled. Whilst making the climb, she is estimated to have produced a power output of 2,030 drawbar horsepower. To put this in perspective, this exceeds the maximum effort of the diesels that were sent to replace her… She has been to Scotland, recreated the famous Bristolian non-stop service and recreated the Great Western service of the 9 May 1964. She has recently returned after a 10 year overhaul and it is a real privilege to have one of No 5043’s first trips to come and see us at Didcot.

5043 on the turntable at Didcot, 4 March 2023

The day was amazing and we are very grateful to Tyseley and Vintage Trains for their part in making it all happen. So much so, that Pendennis Castle will be making a stop on her way home from her 2023 tour to be a guest at the Tyseley Locomotive Works Open weekend on 17 and 18 June where, ‘Four Castles’ will be repeated. This time No 5080 Defiant will take the place of our No 5051 Drysllwyn Castle. Why not show support and book a ticket?

FRIDAY 3 MARCH

100 Years and 4 Castles, Part 5 - The Last in Line and the ‘Castle G.T.I.’

It’s here – just one more day to wait until the Four Castles event. Really exciting stuff, right?! I can’t wait. Should be amazing.

Last time we chatted, we saw the Second World War looming on the horizon. This meant two things for the Castles. Firstly, their production came to a temporary halt. There were two engines scheduled to be built before the start of hostilities – the two that rounded out the 50XX series, Nos 5098 and 5099. But an edict from the government that no express passenger machines were to be built at least curtailed that for now.

No 7000 Viscount Portal, built in May 1946, leaving Dainton tunnel with a Liverpool to Penzance express. Viscount Portal was the last Chairman of the GWR. Photograph by John Ashman

The second was that they became just another device for moving whatever to wherever. Total war, as WWII was, meant the glamour and prestige that the Kings and Castles enjoyed just evaporated. The railways were turned over to the war effort. One poster from the newly formed Railway Executive Committee proclaimed ‘All Clear for the Guns’ and another asked ‘Is your journey really necessary?’, with a painting of a soldier point his finger out from the image.

Speed restrictions, massive freight and personnel movements as well as evacuations and preparations for operations made the lives of footplate crew very difficult. All steam locomotives were subject to blackout precautions, with their cabside windows plated over and heavy canvas screens erected to hide the light given off by the fire from enemy aircraft. This severely restricted the vision of the crew and kept the heat in to a ridiculous degree.

A view inside the cab of No 7001 Sir James Milne, built in May 1946. Sir James was the last General Manager of the GWR before nationalisation and the locomotive was given his name in February 1948, having previously been Compton Castle. Note the oil gauge for the mechanical lubricator, partially hidden by the driver’s left hand

Externally, the intricate lining applied to the engines pre-war went – there simply wasn’t the time, the manpower or the materials. Most engines in the UK were painted plain black in wartime when they needed repainting, but the vast majority of the Kings and Castles remained plain green. Two Castles did get the black paint scheme however… The engines simply soldier on.

There was a commemoration of the Battle of Britain, beginning as early as September 1940 – when the battle was very much undecided. Remember that the historically recognised turning point is 15 September – known today as Battle of Britain Day. No 5071 Clifford Castle was renamed Spitfire, and all the other engines from 5072 to 5082 were named after aircraft that were fighting with the RAF at the time*.

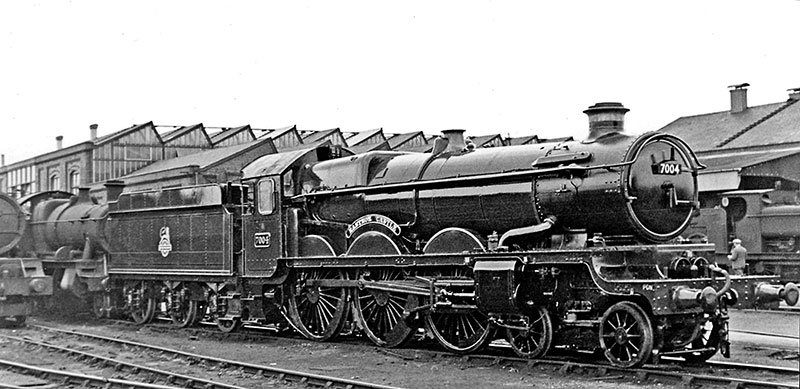

No 7004 Eastnor Castle, built in June 1946, at Swindon Works. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

This means the other Castle that No 4079 will be going to meet at Tyseley in June, No 5080, is one of these – originally Ogmore Castle she became known thereafter as Defiant. As the threat diminished and then disappeared in the victory of 1945, the railways tried to get back to some sense of normality. This was going to be a tough job. There had been a lack of maintenance, renewal and investment during the war and this has been calculated by modern historians to be to the tune of some £11 billion in today’s money. Of the ‘Big Four’, the GWR was probably in the best shape financially of the railway companies, but that wasn’t saying too much.

The production of Castles did resume, however, in 1946. Those last two from before the war finally had their day and Nos 5098 Clifford Castle and 5099 Compton Castle were finally built. These represented the next step forward in that they had the addition of a three row superheater. The situation after the war was that the good quality coal that the GWR locomotives were built to burn was needed for export. The railways were being run on an inferior grade of coal. Not so much of an issue if you have a wide firebox like an LNER A4 or an LMS Duchess, but the narrow fireboxes of the GWR engines are much more susceptible to poor fuel. You can’t make the firebox wider – it has to sit between the frames and the wheels – so you need to get more of the energy out of the coal you are able to burn.

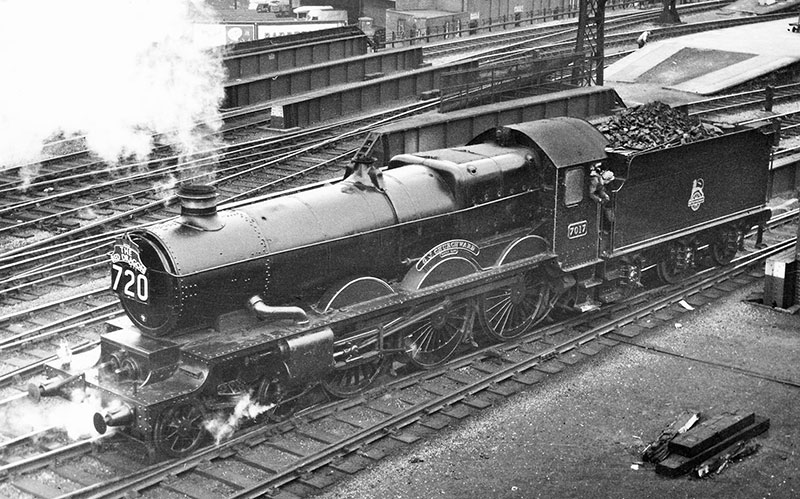

No 7017 G.J.Churchward, built in August 1948, at Cardiff, about to haul The Red Dragon to London. The locomotive had the only nameplates fitted with full stops. Photograph by R C Riley

This is done by increasing your heating area. On the original Castle design, there were two rows of superheater elements. Fredrick Hawksworth added a third and fitted a combined header and regulator valve unit to save space. The step up in performance was welcome at this time of austerity. It’s not to say the two row engines couldn’t do the job, it just required more careful handling to get the same results.

Another fuel source was tried at this time as well – oil firing. The experiment started in 1946 and five engines – Nos 100A1, 5039, 5079, 5083 and 5091 – were converted to burn oil and not coal. By the time the last one was converted in 1948, however, it was realised that the cost of the oil would be hugely prohibitive. They all returned to coal burning soon afterwards.

No 7022 Hereford Castle, built in June 1949, hauling a Newbury Races special through West Drayton in 1962. Photograph by Mike Peart

The lubricator changed again – Nos 5098 and 5099 had five-glass hydrostatic lubricators** but they and the rest of the post-war engines were soon fitted with mechanical lubricators. The reasons for this are many and various but it wasn’t a popular move from the point of view of the drivers who liked the fine control the previous system offered.

No 7032 Denbigh Castle, built in June 1950, photographed at Taplow station on 1 January 1962 after a blizzard the previous night

Gather round again for serious nerd time – look at the handrail under the cab window. On these later engines it wraps up around the side window. The ones on the early engines are straight. A square edged inside valve cover – a far cry from the elegant fluted Vauxhall look of early years – was introduced, but this was seen as a modification on many earlier Castles therefore isn't so indicative. Hawksworth's all welded tender design also began to show up on Castles from their inception during WWII. This would have been seen fleet wide and No 5043 and No 5051 have both sported this look in preservation.

Serious nerd time: the straight handrail on the cabside of No 4079, and that of No 7017 which curves around the window

The last Castle built by the GWR was No 7007. This too was originally named Ogmore Castle (that name eventually stuck to No 7035!) but to mark the passing of the old company and the nationalisation of the railways of the UK, she was renamed Great Western in January 1948. British Railways Western Region continued to build Castles – the final one being No 7037 which was simply and appropriately named Swindon after her birthplace.

The final step in the evolution of the Castles is the full performance upgrade – the four row superheater and double chimney. No Castle was built with this but a good number were so modified subsequently. Both of our visitors tomorrow – No 5043 Earl of Mount Edgcumbe and No 7029 Clun Castle are examples of this upgrade. There was often no real rhyme or reason as to which engine got the upgrade. For example, neither No 4079 Pendennis Castle nor No 5051 Drysllwyn Castle did although the second one built, No 4074 Caldicot Castle did. This was the biggest departure from the original design but produced some truly remarkable performances. They still do today with our friends at Tyseley!

No 7037 Swindon, the last Castle built (in August 1950) hauling a westbound express through Southall in 1962. Photograph by Mike Peart

From there on in, the slow decline of the steam fleet meant that the writing was in the wall for these fine machines and either preservation or the breaker's yard beckoned. We will take a look at that and the stories of our visitors in next week’s blog – the engines both have interesting and very diverse stories to tell. But it is appropriate to finish by asking why we are going to all this hassle?

Well, think about it. The Castle design effectively starts with the first Stars in the first decade of the twentieth century. They were so good at their job that engines to essentially the same design were STILL being built into the 1950s. It is hard to think of another front line express passenger class that was built to essentially the same design for that long. With not just 171 Castles, but 72 Stars and 30 Kings, it was prolific too and some of these machines clocked up over 2.5 million miles in service. From No 40 North Star’s first moves in 1906, there was a 4 cylinder GWR design in service until No 7029 Clun Castle made her last few revenue earning trips in December 1965. This was a world-beating design that proved just what the UK could do, and just what we are capable of as a nation should we choose to do so again.

*The full list of aircraft being:

Spitfire, Hurricane, Blenheim, Hampden, Wellington, Gladiator, Fairey Battle, Beaufort, Lysander, Defiant, Lockheed Hudson and Swordfish.

**See last week’s scribblings for details…

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.