Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - May 2023 - Going Loco - May 2023

Going Loco - May 2023

FRIDAY 26 MAY

The Heavy Tank Squad - Part 2

Last time we delved into the origins of the mighty Great Western Railway heavy freight tank engines – machines for a singular job, the movement of coal from the mines in the Welsh Valleys to the railhead where the coal was taken on to its end destination. This continued into the 1920s to be a major source of revenue for the Great Western.

No 5243, built in August 1924, was employed for banking eastbound freight trains through the long single-bore Ledbury tunnel when this photograph was taken on 8 November 1958. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

It’s worth talking at this point about the variety in the front ends of these machines. Nerd knowledge point knowledge incoming .… There are versions that have a straight running plate that goes from the front of the tanks to the front of the cylinders and then drops down to the buffer beam. The running plate has a slight bulge in it to clear the cylinders. This is the early arrangement. The later arrangement has a short straight from the tank to the cylinder, an up-turn, a bit of running plate over the cylinder, a down turn and then off to the buffer beam.

Other features of note are that the earliest engines were built with inside steam pipes. If you look on the side of the smokebox of later machines, you will see the seemingly quite large diameter pipes angled down to the cylinders. These are actually only about 3½” in diameter but are well insulated, hence the much larger appearance. They feed the steam from the regulator and superheater header to the valves and thence to the cylinders. In early engines, this was done in the smokebox. The pipes being kept warm by being in a warm place!

Looking fresh from overhaul, compared with her tired condition in the previous photograph, No 5243 is hauling a goods train through Newport station on 5 June 1961. She was withdrawn in November 1964. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

The other thing to note is that like many classes – such as on Mogul No 5322 and Saint No 2999 Lady of Legend – they had what are known to us as the porthole windows in the cab front over the top of the firebox. These aren’t much use to be honest and were eventually removed from most engines that carried them. This is again an early feature carried on up until the mid 1920s. Of course, the replacement of cylinders, boilers and other components led to early engines ending up with some later features so it’s worth also looking at the running number of the engine to determine in some cases at least the likely build date. 42XX numbers are mostly Churchward era (he retired in 1922) and those that have 52XX numbers are pretty much Collett’s engines who took over from Churchward.

Enough nerding …. The 1923 batch of the heavy freight 2-8-0Ts was the first of what became known as the 5205 class. This sort of sub-class numbering is most famous on the Halls / Modified Halls (49XX class / 6959 class) the 28XX / 2884 classes of 2-8-0 tender engines and the 57XX / 8750 classes of pannier tanks). It is used to denote a significant design change in a class but one that is usually not too different from its predecessors*, the big difference here being in the cylinders. The newer engines had 19” cylinders, eking out just that little bit more power.

No 5241, built in August 1924 photographed fresh from overhaul at Swindon Works on 4 Febraury 1962. She was withdrawn in June 1965. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

They were built in, broadly speaking, two batches, the first were numbered from No 5205 (hence the sub-class name) to No 5274. These engines retained the straight running plates of the earlier machines but had the outside steam pipes from new. The second ‘batch’ were numbered from No 5275 (the final sub-class of the 2-8-0s) to No 5294 and the last of the type were built as late as 1940. These were built from new with the raised running plate over the cylinders. Overall, 100 of these engines were built.

Ahh, I hear you cry, Mr Going Loco can’t count! 5205 to 5294 isn’t 100 engines! Well spotted if you saw that and it is due to a little thing called the Great Depression. Perhaps this blog is getting a bit too long now anyway, and we will look at that next time.

Two of these engines survive with the remains of a third being present at Didcot. All were built in 1924. No 5224 has the later raised running plate design which she has received as an upgrade at some point in her service career. She is owned by Pete Waterman and is currently stored out of traffic at Peak Rail, having last worked in 2011.

No 5224, built in May 1924, at Weybourne, North Norfolk Railway, on 21 March 2008 showing the raised running plate over the cylinders. Photograph by Roger Blackwell

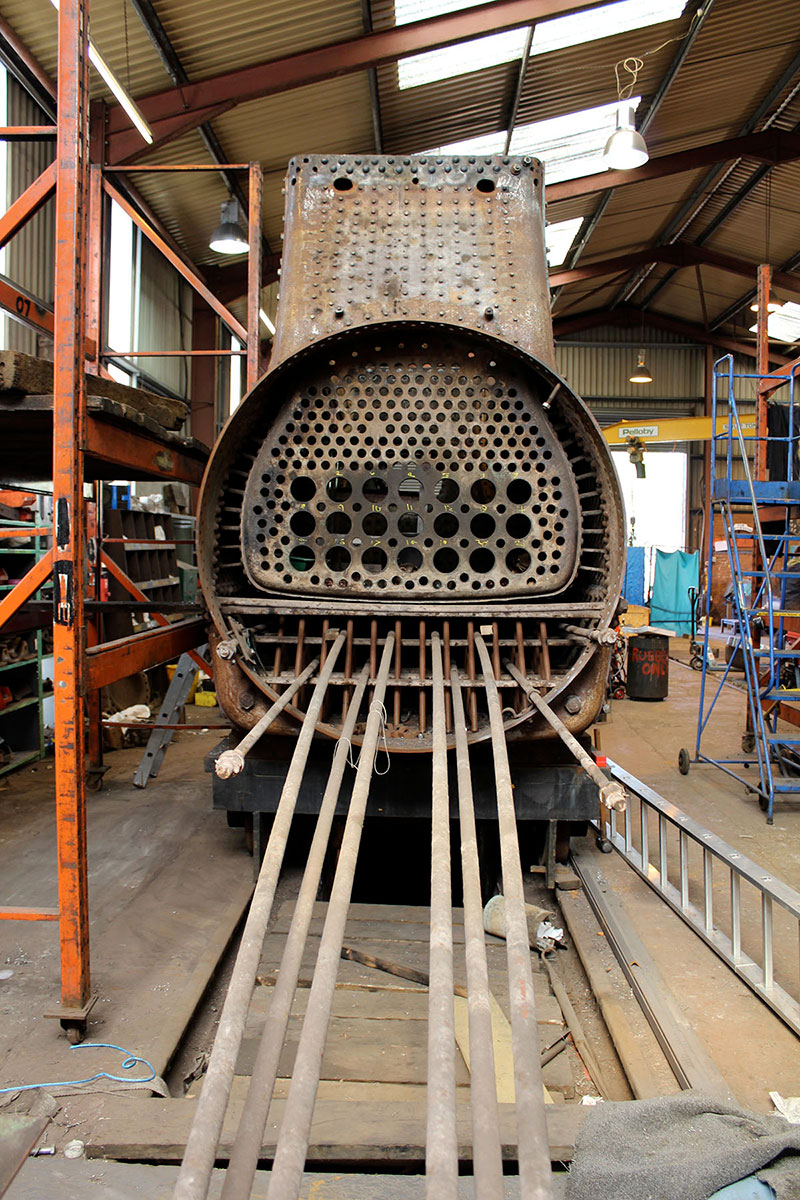

The Dartmouth Steam Railway has No 5239 in their care and they have named this one Goliath as a counterpoint to 42XX class No 4277 Hercules. Also possessing a raised section over the cylinders, happily this locomotive is in traffic and hauling holiday makers up and down the Paignton to Kingswear line. The remains of No 5227 are present at Didcot. She was one of the Barry 10 – the last remaining engines from the famous scrapyard and was not in great condition. Several of her parts have gone on to new lives in other locomotives, however, and the boiler is with our friends on the Churchward County 4-4-0 project as the power plant for No 3840 County of Montgomery. The remains are now privately owned.

No 5227, built in June 1924, as she first arrived at Didcot with many parts removed. Since then her boiler has gone to the Churchward County 4-4-0 project

In the words of Yoda however – “There is another …” A mighty mutant beast that has become legendary as the only class of locomotive that was in Barry scrapyard and is yet to turn a wheel in preservation. Next time we will look into the economic disaster that gave birth to a successful and powerful asset to the GWR. The 72XX class and the week after, we will see what we are doing to make sure that there are NO classes from Barry Scrapyard that have not turned a wheel in preservation!

*The outlier here being the 40XX Star and 4073 Castle classes. There was quite a bit of difference between the two …

FRIDAY 19 MAY

The Heavy Tank Squad – Part 1

The first job of the railways at their inception was to move freight. The first steam locomotives moved freight at mines, and freight is something that remains important to the railway to this day. The Great Western put a lot of effort into developing locomotives that were up to this particular task. Churchward was key to developing these machines and his range of eight-coupled* locomotives became the basis of steam engine design for both the Great Western Railway and to some extent, the rest of the UK.

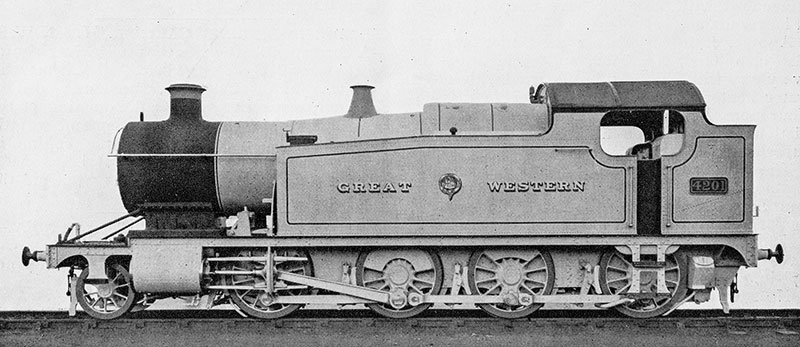

The prototype 2-8-0T – this photograph was published in The Locomotive magazine

Churchward and his team at Swindon developed two main heavy freight types – both with slightly different remits. The first we have met in Going Loco before. The 28XX 2-8-0 tender loco was the mainstay of freight services on the Western until the introduction of the BR Standard 9F 2-10-0s in the 1950s. Even then, the 28XXs were still around until pretty much until the end of steam on the region. They were highly successful and can be seen as the grandfathers of such famous freight machines as the LMS 8Fs. Those were designed by a Swindon man after all .…

The other type is the heavy freight tank engine. Like their tender engine brethren, they too were eight-coupled. Their initial remit was a bit different to the tender engines though. One of the most important commodities transported by the GWR was coal. Welsh coal. This had its own unique challenges as the mines were usually in the valleys of South Wales. These were short but challenging lines with steep gradients and sharp curves between the mines and the railheads where the big freight locomotives would take the coal on to its destinations for industry, export or for use in the GWR’s own locomotives.

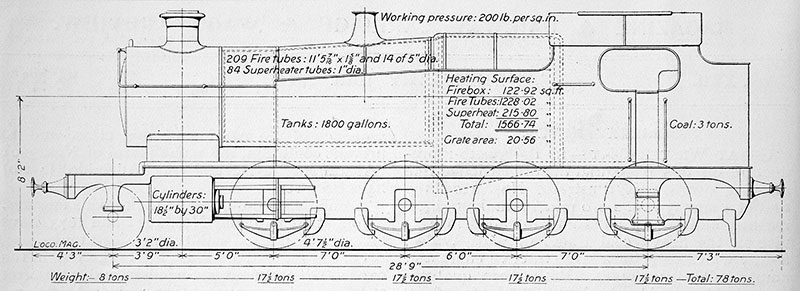

A drawing of No 4201, also published in The Locomotive magazine

The standard machine for this job at the end of the 19th century on the independent railways in South Wales was an 0-6-2 tank engine. The rising levels of traffic and the demand for coal increased and it got to the point that the 0-6-2s were becoming overworked on a regular basis. In the words of a certain motoring television presenter, what was needed was “More Power!” The idea of the 28XX 2-8-0 tender loco was sound – its size wasn’t. Well, that’s ok then – make it smaller! And that is essentially what Swindon did. The boiler was reduced in size from the large Standard 1 to the smaller Standard 4. This boiler ended up being used on a variety of different machines from the City class 4-4-0s** to various type of large Prairie 2-6-2Ts (which the 42XXs have more than a passing resemblance to) and the 43XX class Moguls.

There was also an increase from six-coupled wheels to eight. Now, this might seem counter-intuitive in some ways. Making the engine longer to run on lines with tight curves doesn’t look sensible on the face of it, but there were some clever shenanigans in those wheels. The GWR had a thick and a thin profile to the flanges that were machined into the edges of their wheels. The middle set on all the big 4-6-0s is turned to this thin profile. With the 2-8-0s, the profiles were thick, thin, thin, thick. This started to ease the locomotive in the corners but the next clever move was the inclusion of semi-hemispherical joints in the rear coupling rods and axleboxes with side play for the rear coupled wheels. This resulted in a really flexible wheelbase, reduced from 20ft to 13ft over the coupled wheels, making the engines more than capable of traversing sharp curves.

No 4214, built in 1912, climbs towards Patchway station with a Rogerstone to Salisbury goods train

1910 saw the first of these large tank engines completed, and No 4201 was set to work on a trial that lasted 14 months. The prototype had a straight backed coal bunker that held 3 tons. This engine, like so many machines devised under Churchward’s reign, was an instant hit. She was capable of traversing curves down to two chains***, which for a locomotive that weighs 81 tons is no small achievement! The design was capable of pulling 1,000 ton trains over some pretty serious geography and had a tractive effort that at the end of the production run of these engines in the 1930s topped 31,170lbs. To put that in perspective, the much larger Castle class has a tractive effort of 31,625lbs.

No 4268, built in 1919, at Swindon in the early 1960s. Photograph by Mike Peart

The engines of the first production batch began construction in 1912. The first big modification was the enlarging of the coal bunker from 3 to 3½ tons by adding the curved top section. While this extended their range in terms of fuel, they were always water hungry beasts and their tanks were kept narrow by the restricted loading gauge on the valley lines. Frequent water stops were the order of the day to keep their thirst sated. The next batch saw further increases in coal capacity. By simply making the bunker six inches taller, an extra ½ ton of fuel was added.

No 4274, built in 1920, at Swindon in 1962. Photograph by Mike Peart

Right at the end of the Churchward era in 1921, the final locomotives of this series were begun and ended with 105th example in 1923. This wasn’t the end for the type and its production and neither did it end the history, which was going to take a rather strange turn due to factors way outside the control of the Great Western. While we don’t have an example of the early eight-coupled heavy tanks in the collection at Didcot, there are no less than five examples preserved, three of which have run in preservation. Over the next few weeks, we will take a look at the development of the class, the dawn of Collett’s version and a strange mutant offshoot that is rumoured to inhabit the works at Didcot .…

PS if you would like to see one of these engines, they are here (at the time of writing):

No 4247 at the East Somerset Railway where she is awaiting overhaul.

No 4248 at Steam Museum Swindon. This loco is dismantled and posed as if being constructed. She has never been restored from scrap condition.

No 4253 at the Kent and East Sussex Railway and is under restoration from scrap condition.

No 4270, which is owned by Jeremy Hoskins, was based at the Gloucestershire and Warwickshire Railway but is now out of ticket and at the old Hornby Factory in Margate, Kent.

No 4277 which lives at the Dartmouth Steam Railway, has gained the name Hercules in preservation and is currently operational.

* This means that the locomotive has eight driving wheels, linked with coupling rods – hence the name!

** Like No. 3440 City of Truro from the National Collection.

*** 1 Chain is 66 feet or 22 yards. In modern parlance it’s about 20.1 metres. And if you are very bored, it’s also 4 perches or rods long. And 1/10th of a furlong. I’ll stop now .…

FRIDAY 12 MAY

The County Set

Hello again and welcome to another one of those situations when your regular writer gets a week off! It’s great talking to you all but it’s also nice to let someone else have a go once in a while – you don’t want to read me wittering on all the time do you?! In recognition of the recent County Project Fundraiser Day, I thought we had better take a look at the project and David Bradshaw stepped up to have a chat with you all about the project, its aims, where they are right now and what’s in the future. Take it away David!

1014 looking impressive on 22 April 2023

In 2005, the much stripped frames of Modified Hall No 7027 Willington Hall, a long-term resident of Barry Scrapyard in South Wales, appeared at Llangollen Railway Works where she was dismantled and, using the drawings prepared by the late Pete Rich, the frames were modified to accommodate what was to be the much modified boiler from Stanier 8F 2-8-0 No 48518, also a long term resident of Barry Scrapyard. So the 31st Hawksworth County was born. Numbered and named 1014 County of Glamorgan in recognition of the contribution made by Dai Woodham to steam preservation, an almost complete No 1014 made her first public appearance at Didcot where she is being assembled at a Supporters’ Day held on 22 April 2023.

7927 leaving Barry

The Hawksworth County was a development of his Modified Hall, utilising the larger LMS designed 8F boiler, examples of which had been constructed at Swindon during WW2 and the Modified Hall chassis with larger (6’3”) driving wheels. The other changes to the design involved beefing up the outside motion to accommodate the higher pressure boiler, an alteration to the rear stretcher to allow the sloping throatplate of the 8F boiler to fit, a wider cab and matching wider flat sided tender.

The frames newly modified at Llangollen

We chose to recreate the County in her later form with the distinctive double chimney acquired from 1006 County of Cornwall as it was in this condition that they were at their most effective. Apart from the three 6’0” driving wheelsets which still reside at Didcot as a spare set for any Hall owner who might need them, all the items acquired when 7927 was bought (for £1!!) from her owners the Vale of Glamorgan Council have been re-used either in the construction of 1014 or other GWR locos, in particular 6880 Betton Grange which inherited the No 1 boiler.

The frames on arrival at Didcot

Over the years following the launch, steady progress has been made on the build, from manufacturing the all-important 6’3” driving wheels, to all new outside motion, splashers and running plate, cab and a new Hawksworth tender built around the running gear from a redundant Collett version. The boiler from the 8F was shipped to Crewe Works where the firebox was reprofiled and following transfer to HBSS (Heritage Boiler Steam Services) in Liverpool a new barrel to the correct length and profile was fitted. In 2022 the part completed boiler was shipped to Didcot where the new smokebox was attached and the whole assembly was fitted to the frames. It is in this condition that supporters were able to see the loco on 22 April.

The unmodified 8F boiler arriving at Didcot

The casting of one of the driving wheels

The driving wheelsets transported to Didcot

Progress on the frames in 2015

Driving wheels being fitted to the frames

The story behind this rebuild owes its inspiration to the late Pete Rich who in 1973 persuaded the GWS to buy Maindy Hall from Barry with the intention of back converting her to a Churchward Saint No 2999 Lady of Legend which is currently wowing admirers around the country. This will be followed by the launch of 6880 Betton Grange later in the year and 1014 by late 2024 or early 2025, with others to follow.

The steam exhaust assembly

The exhaust assembly fitted in the frames

These locomotives are the ultimate tribute to George Jackson Churchward, CME of the GWR from 1902 to 1921. They will provide the GW enthusiast with the unique opportunity to see an example of all GWR 4-6-0 types in steam at one time, with the exception of a Star which is represented by No 4003 Lode Star, a static exhibit.

The smokebox

With the smokebox fitted, 1014 was posed with 2999

1014 with smokebox on the turntable

The photos depict the story from 2005 when 7927 left Barry, through the modification of the frames, the six new driving wheels, new superstructure, new outside motion, firebox rebuild, new boiler barrel, new smokebox and saddle, new tender frames and tank and finally of the loco on display at Didcot, with just over £100,000 to raise to finish the job.

The tender frames under construction

The new boiler barrel at HBSS

The modified 8F firebox at HBSS

The boiler trial fitted in September 2022

The Supporters’ Day, held on 22 April, was an opportunity for those who have contributed significantly to the recreation of 1014 to see for the first time the loco with the boiler fitted.

The day began with the engine being moved to the traditional position opposite the cafeteria. Richard Croucher, Vice President of the GWS and chief fundraiser for the project welcomed guests; John Buxton from Cambrian Transport who had represented the Vale of Glamorgan Council, owners of 7927 Willington Hall in negotiating the Three Counties, 47XX and Grange agreement with the GWS; and Andrew Dakin who had represented the Welsh Development Agency in the same negotiations and who had steered the group through the discussions with the Heritage Lottery fund who had funded the original purchase. John very kindly presented the project with £500 to help towards raising the outstanding £150,000 required to complete the locomotive. To date over £1,250,000 has been raised. Later on in the day the locomotive was moved to the turntable where supporters and visitors were able to photograph her facing both east and west.

New 1014 numberplates

Work remaining to complete 1014 is as follows:

• Finish the tender tank – estimated completion, end of August 2023

• Fit inside and outside motion – estimated completion, late autumn

• Fit cladding – estimated completion, end December 2023

• Locate/manufacture backhead fittings, smokebox fittings, main steampipes and other miscellaneous items

• Complete boiler which will be undertaken by HBSS at Huyton, Liverpool – this requires fitting the, tubeplate, internal fixings and acquiring new superheater header, tubes, grate and ashpan.

A connecting rod ready for machining

Motion parts at Didcot

Prior to the latest fund raising push we required £150,000 to complete the engine.

This figure remains just into six figures but is expected to reduce during 2023. The final push which will involve the completion of the boiler is expected to take place in spring 2024 with a first steaming in late 2024/early 2025. Current amount raised is circa £1,140,000.

1022 County of Northampton ex-works, looking as 1014 will appear when finished

1014 on the turntable during the County Day on 22 April 2023

Thanks David! It’s certainly come a long way from that set of bare frames I saw delivered all those years ago. There is still a lot to do so if you feel that you are able and willing to contribute to the rebuild, please download the 1014 Appeal Form.

Back to normal next time. It does mean I have to decide what we are talking about though.

Errrrrr…

I’ll get back to you on that…

FRIDAY 5 MAY

The Diesel Away From Home…

There has been a significant, if temporary, addition to the motive power collection at Didcot. It’s big, it’s blue and unlike the two ‘Didcot Kings’, it's a blue locomotive that I can’t quite see where the coal goes. Apparently it runs on some sort of liquid coal? ‘It will never catch on you know’, thought I…

No 1023 on arrival at Didcot on 30 January 2023

Well, apparently it did catch on and in rather a big way! Post 1960, it had caught on almost wholesale on the Western Region. The reign of steam was at an end and the new generation of (then) modern traction was coming to the fore. For the former Great Western, electrification simply wasn’t an option at the time and experiments with gas turbine powered locomotives were of mixed results at best. This left them with diesels. But, that independent streak that went with the Great Western was still there and rather than opting for the usual diesel-electric locomotive designs, Swindon went diesel-hydraulic.

Compared with the svelte diesel-hydraulic Warships of the same era, diesel-electrics of the late 1950s were galumphing brutes that had to be carried on 8-wheel bogies

The majority of diesels are powered by their engine driving an electrical generator, which in turn drives electric motors to turn the wheels. In the diesel hydraulic machines, the engine drives a hydraulic transmission. The advantages of this type of transmission is that it theoretically makes the locomotive lighter. This should have several advantages including power-to-weight ratio, wear and tear on both the machine and the infrastructure and so on. The Warship class diesel-hydraulics produced 2,200hp with an overall weight of 78 tons, while diesel-electrics of similar power output weighed over 130 tons.

The return journey of Winston Churchill’s funeral train from Handborough to Paddington, on 30 January 1965, was entrusted to 1015 Western Champion

By the early 1960s the Western Region had the Warship and Hymek diesel-hydraulic classes in operation but these, while capable, were not quite up to the task of pulling the top expresses in the same manner as their Castle and King forebears. They just didn't quite have the power.

When the 2,700 hp Westerns were limited to 7 or 8 coaches on the fastest schedules to the West of England in the late 1960s, two of the older Warships were run in tandem to give 4,000 hp and keep time with 11 or 12 coach trains

A new design was therefore needed and this upped the power to 2,700hp from its two diesel engines in a locomotive weighing 107 tons. Hydraulic transmissions had their issues. It wasn't possible to put the full amount of power down to the track because there wasn't a single hydraulic transmission that was capable of both taking that power and fitting within the narrow British loading gauge*. Split the required horsepower over two engines and you bring it within the limits.

The body shell of this new locomotive, like the earlier Warships, used the stressed skin style of building technique. Earlier diesels used huge, I section girder frames and as a result they were fairly heavy. The idea of a stressed skin is akin to how an aircraft is built. The skin is stretched taught on the frames of the body. It actually forms part of the load bearing structure instead of just being there to keep the weather out!

The class was ordered in 1961 and the 74 machines were split with 30 being built at Swindon and 44 built at Crewe works. The class were initially going to be named after beauty spots in the Western Region but the naming convention became that each member would be given a name with the prefix ‘Western’. Which gave rise to their class name. They took the numbers in the 1000 series – but with the prefix ‘D’. This is of course because the Hawksworth 1000 County class 4-6-0s were still (just!) in service.

No 1023 at Didcot

There were a few teething troubles – not least of which is that the engines in the prototype No D1000 Western Enterprise had its engines directly behind the cabs and caused a great deal of noise. A redesign was needed. The fact it had two engines eventually became a bonus. Trains that would have been stopped dead by a loco losing its one and only power plant were kept rolling, if not exactly quickly, by the remaining engine on the Western. One factor never really sorted was that the top third gear was geared a little too high for the engines and could cause difficulties when the loco was getting near to its top speed.

They were later upgraded to have an air brake mechanism fitted to enable them to work on more modern coaching and freight stock. Despite being largely a success, the Western only had a short tenure as the flagships of the ex-GWR. Their non-standard nature, the fact that you couldn't fit electric train heating to them and the cascading of other classes of diesel-electric machines to the line meant that they were prime candidates for early withdrawal. The last went in 1977. Happily though, no less than seven of these characterful engines have been preserved.

Railcar No 22 and No 1023 now displayed in the loco works at Didcot

The example we have staying with us for the next five years is No D1023 Western Fusilier. It was built at Swindon works in 1963. It was out-shopped in the striking maroon livery but eventually succumbed to the corporate blue livery it wears today. It got its claim to fame hauling the Western Tribute railtour on 26 February 1977. This was double-headed with No D1013 Western Ranger (also happily preserved) and was the last Western hauled service on British Rail. Upon withdrawal in 1977, it was placed in the National Railway Museum at York, where it has been part of the national collection ever since.

Sadly, No D1023 isn’t operational – one of her complex hydraulic transmissions is unserviceable and the museum has no plans to restore it. Still, it does give us all a chance to see up close, what your writer at least considers one of the best looking diesel locomotives ever built in the UK. Not just that, she is back on her home territory too. So why not come and see Western Fusilier while she is with us? Currently she sits alongside our GWR diesel railcar No 22, providing quite the contrast between the designs of 1940 and 1961. It really does show the ‘white heat’ of technological pace that the time period embodies.

*The largest a locomotive or other piece of rolling stock can be before it starts hitting bridges and tunnels and the like. Ours is small as we invented the modern railway and who thought trains would ever need to be that big in the mid 19th Century?

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.