Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - July 2023 - Going Loco - July 2023

Going Loco - July 2023

FRIDAY 28 JULY

The Last Post?

There are a great deal of things that we don’t think of as once being the preserve of the railway. Mail – in the eyes of individuals below a certain age of course(!) – is definitely one of them. At one time, the railways were a vital artery in the circulatory system that is mail distribution. Didcot is home to a fantastic and rare Great Western Railway example of the rolling stock associated with this task.

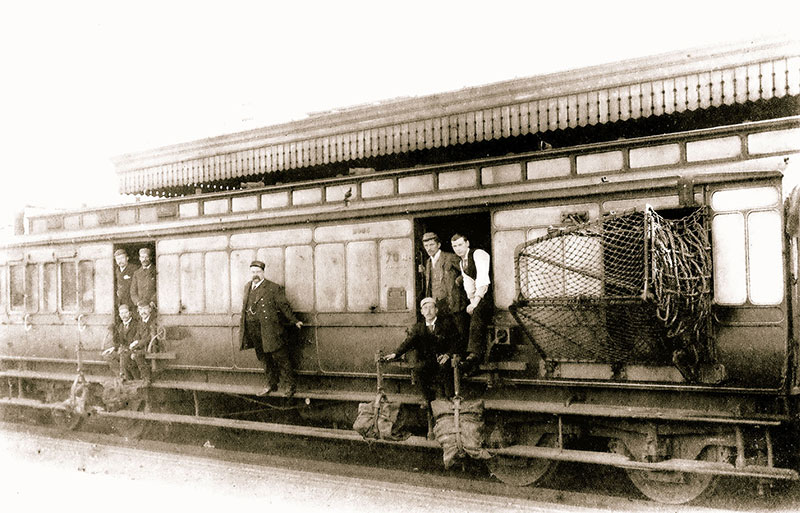

TPO vehicle No 2085 attached to the 5.30 am from Paddington as the London & Bristol Sorting Carriage at Didcot in 1892 or 1893. While the locomotive takes water the post office staff have lowered the net and traductor arms as a demonstration for the photographer. Great Western Trust photograph

The moving of post by rail started not long after the dawn of the railways. Post was carried on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway on 11 November 1830. Shortly after this, in 1838 the Railways (Conveyance of Mail) Act legally obliged the railway companies to transport the post and as a result, the act also demanded that rolling stock be provided so that the mail could be sorted en-route. The first example of this was devised by one George Kastadt. He was a surveyor for the General Post Office or GPO. His concept was put into practice by converting a horse drawn mail coach into a railway coach. Inside, the sorting of mail as it travelled was a major time-saver and the first Travelling Post Office or TPO ran in early 1838.

Another photograph with a member of post office staff demonstrating how to lower the traductor arm under the weight of the mail pouch. Note the safety bar to prevent him falling out while the sliding door is open. The GR scroll signifies this is during the reign of King George V. Great Western Trust photograph

The other big innovation for the TPO came shortly after when Nathaniel Worsdell* built a set of gear to allow the picking up and dropping off of mail en-route. He offered the patent to the Post Office who then decided to come up with their own version designed by John Ramsey. This was put into trial use between Boxmoor, Leighton Buzzard and Berkhamsted on 14 June 1838. The design was improved by Mr John Dicker – inspector of mail coaches – and by doing so put it within the remit of Worsdell’s patent. Nothing is ever easy .… This final design had to wait until 1852 to be introduced, but once it was, it really didn’t substantially change until the end of this practice in the second half of the 20th century.

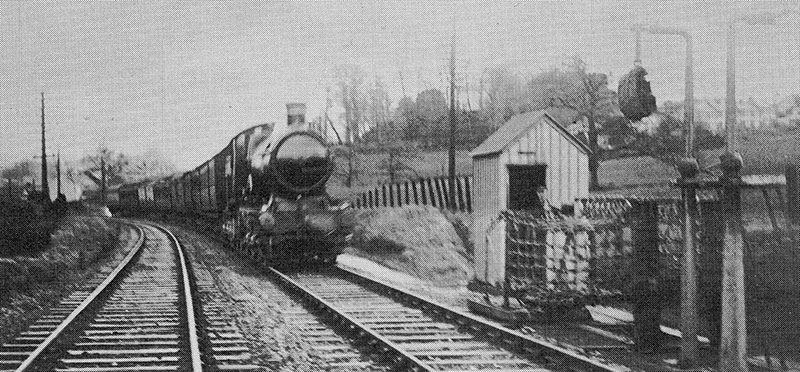

The down Bristol & Penzance TPO approaching the lineside apparatus at Totnes on 15 December 1911. The slight camera shake can be forgiven with the train bearing down on the photographer! This photograph was published in Great Western Echo in 1976

The apparatus was fairly simple in concept. The mail bags to be picked up were held on arms on metal posts on the lineside, and the side of the coach had a large fold-out rope net in a metal frame that would swing out with the operation of a lever. A sliding door in the side of the coach was opened and the 50lbs to 60lbs thick leather mail pouches would slam into the coach at up to 60mph! The reverse was true of the setting down apparatus. The arm on the coach – known as the traductor arm – was spring operated. When it did not have the weight of a mail pouch, the springs held it within the loading gauge. When the arm was loaded, it would swing down and out. The moment the rope net on the line side gear caught the pouch, the weight was relieved and the arm would snap smartly back into position.

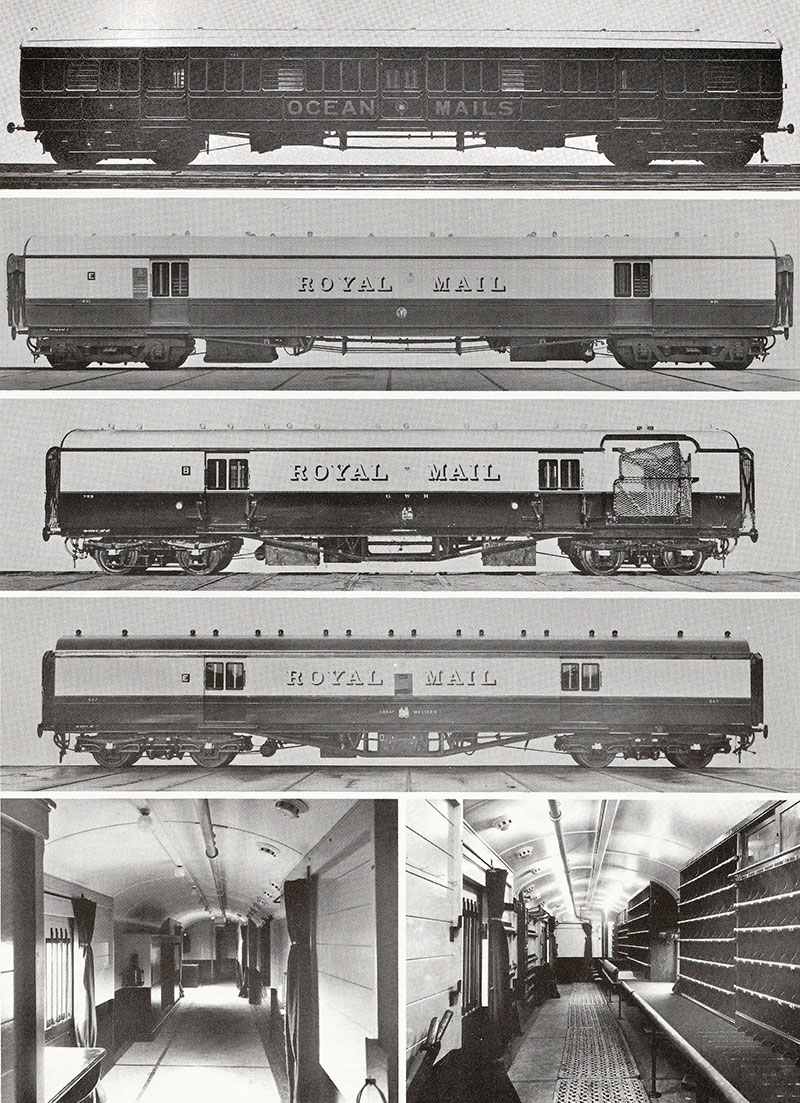

A page of TPO photographs published in Great Western Echo in 1976. From top: Ocean Mails stowage van No 822 in chocolate lake livery; Dreadnought sorting van No 831 built in 1905, in the livery of the mid 1930s; stowage van No 795 built in 1933, in the livery of the early 1930s; sorting van No 847, built in 1947, in the post-war livery. The interiors are, left, stowage van No 795 and right sorting van No 799

The lineside apparatus was meant to be set up ten minutes before the mail train arrived, although this wasn’t always possible. A yellow and black chequered panel warned the driver and firemen of the approaching restricted clearance that the exchange gear represented. The postal workers were alerted to the impending exchange by long white rectangular boards. A hut was provided for the postmen to wait for the exchange and they were warned of the approaching train by a bell operated by the local signal box.

Setting up the TPO ground apparatus at Didcot in 2011. The mail pouch is heavy to lift!

Of course, it didn’t always go to plan. If an expected drop didn’t happen, the lineside operatives were expected to search up to 400 yards in either direction to find the assumed missing pouch. Sometimes the pouch broke open and mail was spread over the track. Occasionally, a track maintenance crew had to be called out to assist in rounding up the now airborne mail. In one particularly difficult situation, divers were called to retrieve the mail – a pouch having been ejected from the train to land in a nearby canal…

Once the pouches are hung on the apparatus, string is tied to the bottom to prevent them being blown into the side of the train before they are caught by the net

Another memorable situation occurred St Austell in Cornwall. The pouch was discovered to be overweight so the practice was to eject the pouch onto the nearby passenger platform.** In an inexplicable move, the operative decided to take down the safety bar that went across the door to prevent people falling out. Needless to say, he went out with the pouch. Fortunately he landed on top of the pouch which saved him from everything but minor injury to all but his pride. His colleagues pulled the cord and stopped the train and when he got back on board, his supervisor handed him a Form P18, which asked why he had left the train without permission.*** You have got to love the bureaucracy .…****

The pouches about to be caught in the net

Our example of a GWR TPO is coach No 814. The original No 814 was built in 1933 to diagram L23. It was 50ft long and had the recesses in both sides for the exchange gear although this wasn’t fitted until 1937. This was done to allow them to exchange mail at Liskeard. It also had the interesting wide, offset corridor connections, the idea here being to allow more room for sorting, etc. inside the coach. This meant that an ‘adaptor’ coach was needed to allow them to attach to regular rolling stock. These full brake vehicles had the wide offset connection at one end and the narrow, central one at the other.

Michael Portillo operates the lever to open the net of No 814 on one of his Great Railway Journeys, while watched by the film crew

As you might guess from the past tense being used all over that last paragraph, our No 814 isn’t the same one. The original was involved in an accident at Hay Lane, just outside Swindon and was so badly damaged that it was scrapped. A replacement was built in 1940, but due to the war, TPOs were suspended and it didn’t enter service proper until 1945. Nos 812, 813 and the new 814 were transferred to the Southern Region in 1967 and were painted green to operate on the London Bridge to Dover service. They were returned to the Western Region in 1972 after they were replaced on the SR by British Railways-designed vehicles. No 812 was scrapped but Nos 813 and 814 were painted blue and grey and used in the ENPARTS role (delivering components for rolling stock around the region).

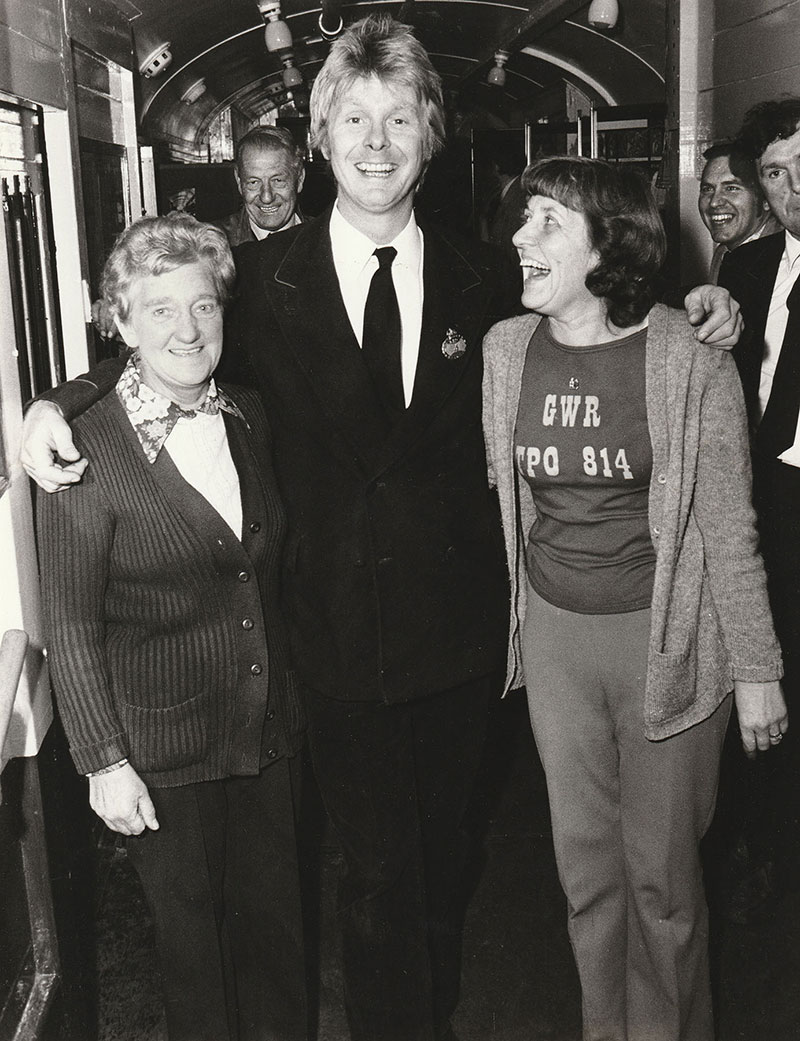

Singer Joe Brown officiated at the launch of No 814 after restoration

They were commonly seen on the yard at Didcot and of course, that sort of thing makes them obvious to a bunch of GWR preservationists .… When they came to be put up for scrapping in March 1975, the GWS put in a bid for No 814 as it was in the best condition (being relatively newly constructed of course!). The net and arms were already in store at this time so there was obviously a plan! No 814 and the lineside equipment have all been restored to working order. In fact, it won the Scania Transport Trust award in 1997.

2-6-0 No 5322 performing a TPO demonstration in 2012

Demonstrations of the coach used to be given but for various operational reasons, this isn’t possible at the moment. The coach is however, on display and you can see part of the environment where these hard working men sorted the mail at a rate of up to 70 letters per minute with all the inherent the dangers of large leather mail pouches being decelerated from 60mph to zero in a very short distance through the open side of a running train. We often talk about unsung heroes – well, here are some everyday heroes that kept the country running. To a greater extent, without the knowledge of the general public.

* Interestingly, his dad had helped the Stephensons build their famous engine Rocket and two of his sons became locomotive engineers.

** Can you imagine the reaction of modern health and safety types to this?!

*** Rule 10 of the TPO regulations clearly states that: “Having taken up duty, officers are not to leave the mail without the sanction of the officer in charge.”

**** The ejected gentleman’s response to this is sadly unrecorded.

FRIDAY 21 JULY

Mysterious Medical Marvel

…. and another thing I haven’t had a chat with you about in a while is coaches. I did a survey of all my blog subjects recently – I’ve done so many now that I need to make sure I don’t start repeating myself – and by far the Didcot vehicles getting the least love in my blogs are the coaches. I am a member of the loco department and I have a thing about built models of wagons*, so the coaches seem to have fallen by the wayside a bit. Also on the theme of fallen by the wayside is the subject of today's blog – it’s another of those things at Didcot that you can't see for reasons that will become apparent!

Ambulance Train No 18 behind Star class 4-6-0 No 4037 Queen Philippa. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

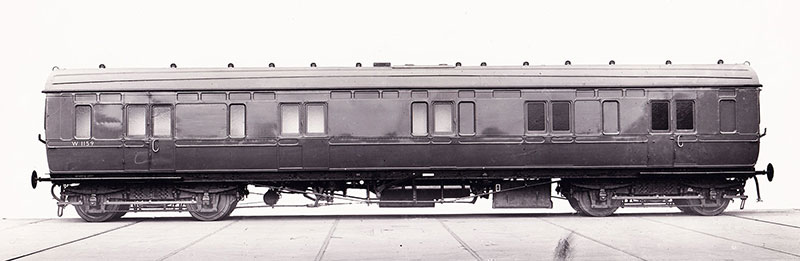

Vehicles with a medical connection are an interesting part of the Great Western Railway’s history. Our example of this type of vehicle is a very interesting vehicle indeed. No 1159 was born of humble origins, being a brake third (a third class coach with a guard’s compartment) built in December 1911 to the ‘Toplight’ design. This was a highly successful design of coaches that were first produced in 1907. Their name refers to the small upper windows or ‘lights’ that were positioned above the main side windows. No 3551, as it was originally numbered, didn’t last long in this form however as the outbreak of WWI changed her fortunes forever.

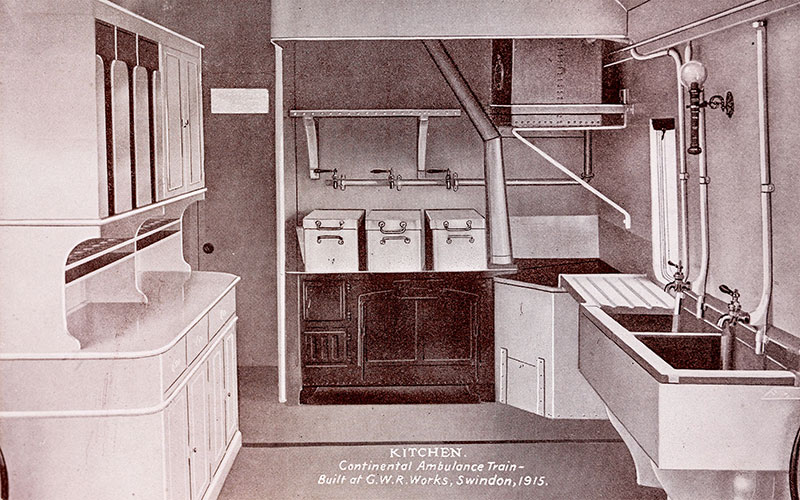

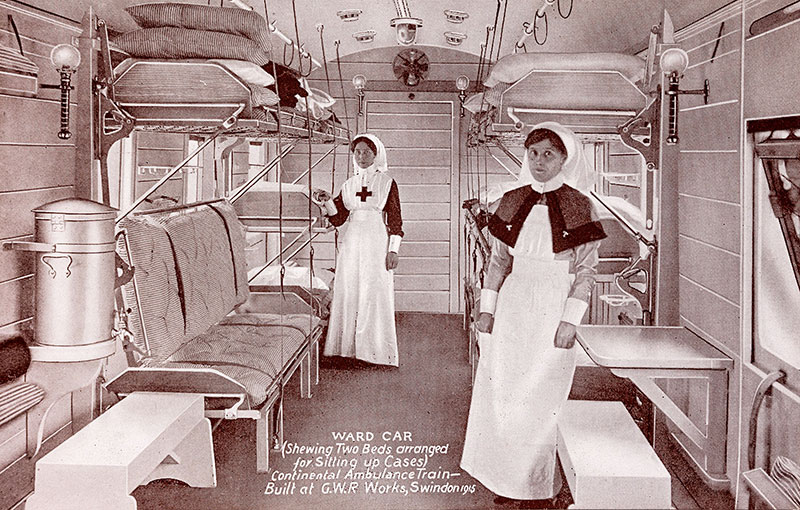

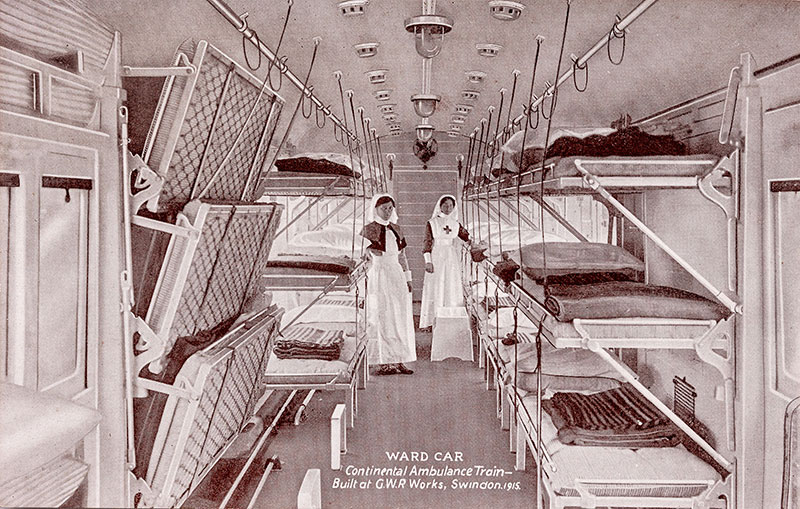

One of a series of postcards showing interiors of Ambulance Trains published by the Great Western Railway. A complete set is in the Great Western Trust collection

In 1916 she was purchased by the government and from here it was converted for use in an ambulance train. These were used in the First World War to transport wounded or sick soldiers from the battlefield to the coast from whence they could be taken to medical centres on the continent or back to the UK for further treatment. We have good descriptions of these trains from the GWR staff magazine as they were occasionally put on display at major stations on the network. Visitors were charged an admission fee which went to war funds. No 3551 was part of train No 27 which was one of those that went on tour before heading to the continent. The trains were quite long – totalling 16 coaches – and were comprehensively equipped for the day. The train’s total weight was 442 tons and they were 960ft long.

Inside there was room for 482 patients who were apparently arranged thusly: 144 were lying down, 320 were sitting up and 18 were described as ‘infectious’. The total staff was 45 members, including 3 surgeons, 4 nurses, 6 cooks and 32 orderlies. The vehicles were all equipped with Westinghouse air brakes and steam heating equipment to enable them to be hooked up to locomotives on the continent. The steam engines in the UK mostly used vacuum, not air brakes. There were independent boilers on board to heat the coaches when in a siding and not attached to a locomotive. They were also equipped with electrical lighting systems supplied by J Stone & Co Ltd. Confidence in these was not total however as also provided were candle lamp brackets in case of failure .…

There was also electrical ventilation – 30 fixed fans and two portable fans in stores. The portable ones were apparently good for helping those soldiers who had been poisoned by gas attacks. The toplight design and roof ventilators enhanced this feature still further. The gangways between the coaches were extra wide and this meant that it was easier to manoeuvre a casualty on a stretcher along the train. It must have been quite the welcome sight for a wounded ‘Tommy’ to see the ‘hospital on wheels’ as they were sometimes known. Someone else who was grateful to see the train was described in the GWR staff magazine:

“A small boy walked from Poplar to see the train, and put his only penny in the platform slot machine under the impression that the possession of a platform ticket would cover the inspection. His interest in the train was fully gratified, notwithstanding his lack of funds, and he now thinks the Great Western a very kind and sympathetic company.”

No 3551 served until the end of the conflict. In 1925 it was rebuilt – not back into the original brake 3rd configuration – but into a passenger brake van or full brake. This was undertaken in 1925 and was done to diagram K36 as part of lot No 1344. It was then that it gained its new identity as No 1159. As quite a workaday piece of equipment, it continued to serve until the end of the Second World War.

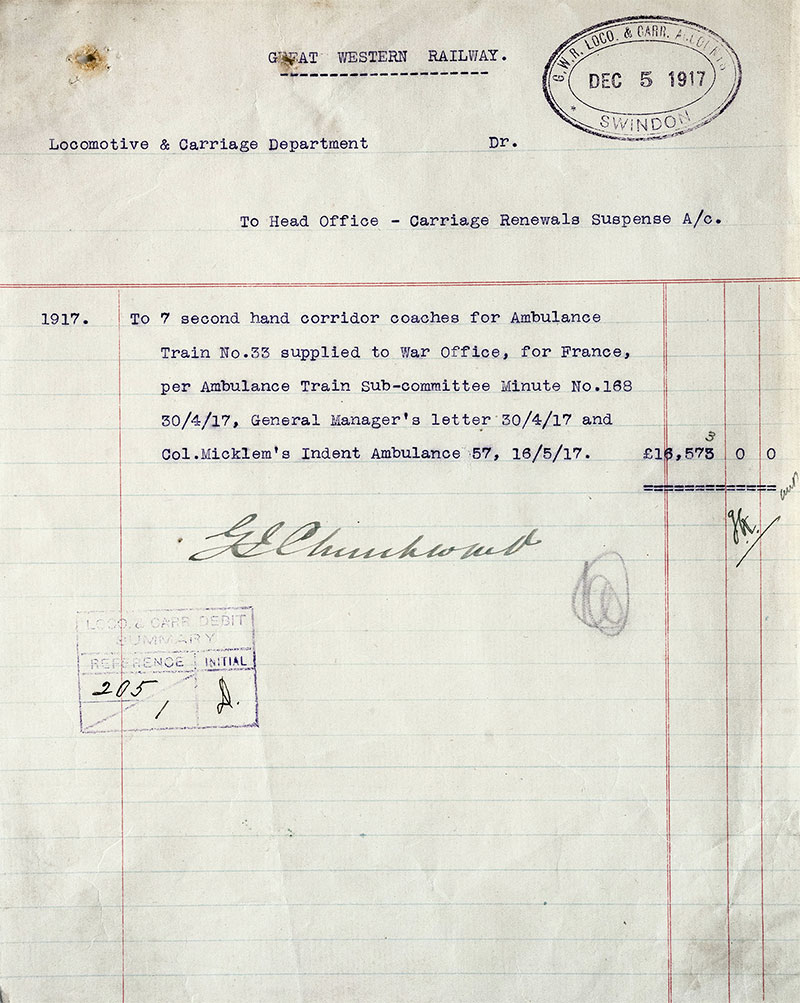

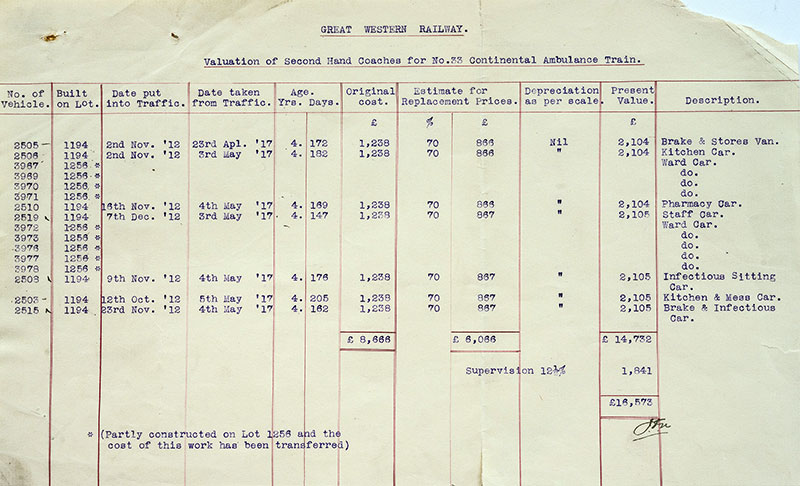

An invoice for supplying seven second-hand coaches for Ambulance Train No 33, signed by G J Churchward, the Chief Mechanical Engineer. Original document in the Great Western Trust collection

This is when No 1159’s second brush with the medical profession occurred. In 1945, it was determined that the medical examinations which were carried out by the GWR were perhaps better undertaken by taking the doctor to the patients, rather than causing large numbers of patients to travel to them. In the spirit of those WWI and WWII ambulance trains. A kind of mobile doctor’s surgery was envisioned. No 1159 was converted to diagram M33 and became what was known as a ‘Medical Examination Coach’.

A valuation of the seven second-hand coaches in Ambulance Train No 33. Original document in the Great Western Trust collection

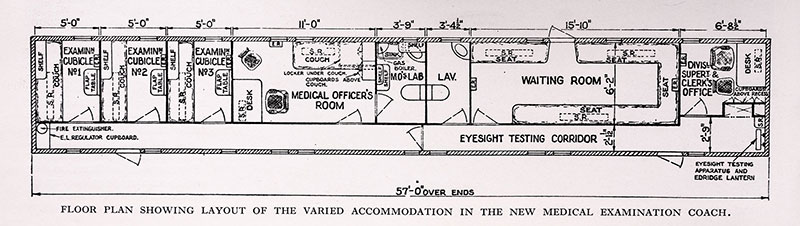

It contained a compartment for the medical officer and a ‘fully equipped’ laboratory for him to use. There were three examination rooms at one end which looked a little like a sleeping coach compartment, with an examination couch and fold up tables within. A waiting room was provided which had benches and coat hooks supplied. At the opposite end was the medical officer’s clerk’s office. A lavatory was in the middle of the coach and part of the corridor was converted so that various eyesight tests could be performed. It had electric lights throughout that could be either run off the on board batteries or a shore supply when available. There were two heating systems as well, the usual steam version as was the norm, and a second electrical one, again for use when parked up in a siding.

The Medical Examination Coach photographed on 26 January 1950. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

It stayed in service as such until it was withdrawn from this task in 1960. Even then, it still had a part to play. Renumbered for a third time to ADW 150294, it remained in departmental service – as a support vehicle for those working on the railway – until it finally found its place with us in the collection at Didcot in 1975. And that is pretty much it. It remains under cover at the back of the carriage and wagon store, gathering dust but with the destructive hands of time held at bay. It’s a tricky coach to justify the restoration of without having a display space to truly do it justice. It’s one of those never say never, but don’t hold your breath type things.

A plan of the Medical Examination Coach, published in the Great Western Railway Magazine

In the meantime however, No 1159 stands as a silent and yet fascinating vehicle. A witness to both the inhumanity of war and the humanity displayed by those that cared for those injured warriors who fought for what they regarded as the land fit for heroes.

*Don't judge me…

FRIDAY 14 JULY

Personality Profiles – Frederick Hawksworth

We haven’t done one in a while so here we are! The legacy of Hawksworth always feels a bit like an unfinished symphony in a way. You can tell the chap had ideas and wanted to do things but he was hamstrung by circumstances. He still has an interesting story to tell, however …

Hawksworth was born on 10 February 1884 in Swindon and was a Swindon man his whole life. He was apprenticed to the drawing office of the locomotive works at just 14 years old in 1898. His education continued at the technical institute in Swindon itself and at the Royal College of Science in Kensington, London. We know he must have done very well as his name is on a number of the drawings from the Churchward era. Of interest to us is the fact that he was involved in the valve gear set up for some of the standard types as well as drawings for No 111 The Great Bear, Swindon’s only Pacific.

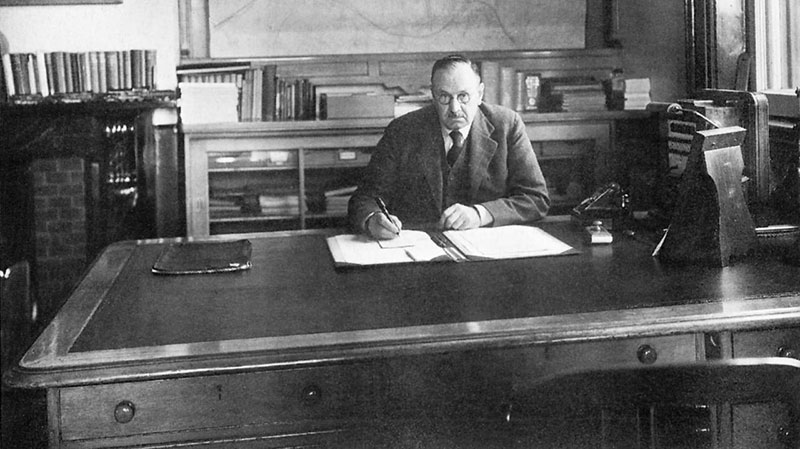

F W Hawksworth in his office, evidently a man with a tidy desk philosophy. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

By 1925 Hawksworth was heavily involved in all the major projects of the day, including the Castles, Halls and eventually the King class. Railway promotion at the time purely rested on seniority. Charles Benjamin Collett had been senior to his chief assistant William Stanier (later Sir William) and therefore Hawksworth had probably reached the apex of his career. This was until Stanier left for the London, Midland and Scottish Railway to become their Chief Mechanical Engineer.

This meant that Hawksworth became assistant Chief Mechanical Engineer to Collett. By 1941, Collett was 70 years old. He had been beset by a number of personal tragedies including the loss of his beloved wife Ethelwyn. This, linked with his pacifist beliefs and Swindon’s war work meant that he left that July. Hawksworth’s work was far more varied than many previous chief mechanical engineer had coped with. Not since WWI had so much relied on the railway works. The list of things produced is quite staggering. Munitions of all sorts were a mainstay but this was supplemented with landing craft, midget submarines, shields and carriages for guns, parts for tanks, as well as the boiler shop being used to treat and harden steel for specific purposes. All this while trying to maintain the thousands of vehicles and locomotives of the Great Western Railway. and build new to make up the inevitable losses. They also produced ambulance trains – 10 of them in total. The coaches in each train were converted into ward cars with bunks, kitchen cars, staff accommodation, a pharmacy and even an operating theatre. Many a service person can be thankful of this particular job of work I’m sure…

Modified Hall class No 7920 Coney Hall when new in September 1950 and fitted with a welded Hawksworth tender. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

His first solo foray into locomotive design was the 1944 Modified Hall or 6959 class. The idea here was to make the production of the existing and excellent Hall class locomotive more efficient to suit the wartime conditions in the works. The largest area of change was at the front end where the frames, cylinders and bogie were much simplified.*

Towards the end of the war, Hawksworth and his team took the Hall 2-cylinder 4-6-0 design to its zenith. Hawksworth took the Modified Hall frames and dropped in a bigger boiler rated to a higher pressure – 280psi to start with. The wheel size was slightly increased and this led to the new 10XX or County class. His influence on tender design was profound. All previous vehicles had been of riveted construction. A time consuming process. He totally turned it on its head and designed an all-welded version that made the whole thing a huge amount easier.

County class No 1007 at Plymouth Laira engine shed in July 1946. The locomotive was named County of Brecknock in January 1948. Photograph by John Ashman

He also produced a small range of tank locomotives that were quite varied in their design. The 16XX class pannier tank was fairly traditional in its layout – really a modernised version of a much earlier locomotive by William Dean. The other two classes were anything but normal. The 94XX was something of a heavyweight - restricted to the ‘red routes’ of the network. This also sported a much modernised look with its pannier tanks stopping short of the smokebox and a more purposeful stance in general. The 15XX class was even more unusual as it had outside cylinders and Walschaerts valve gear – basically a version of the American wartime S100 switcher or USA Tank as it is known to enthusiasts today.

16XX class pannier tanks Nos 1615 and 1665 in Llanelli engine shed on 7 April 1958. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

This forward looking attitude lead to much innovation. He was part of the experiment that saw a number of GWR locomotives converted to burn oil. This was quickly ended when the price of oil went up and supplies of coal in the UK became more reliable. He was instrumental in the acquisition of gas turbine locomotive No 18000. A bold move considering how new jet engines were, even in the air at this time.

He made a great deal of progress with the design and manufacture of passenger coaches too. These had stylish new sloping ends and some even had aluminium sides. The bodies were built directly into the chassis and had very flat sides compared to previous coaches used on the Western. He also looked to the past and was one of a number of people who help arranged for the preservation of the little 0-4-0 well tank No 5 Shannon from the Wantage Tramway.

Three 94XX pannier tanks at Bromsgrove engine shed in July 1964. They were used as bankers on the Lickey incline. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

Everything was moving forward. But as the war finished, the country was on its knees. The railways, having been through the Great Depression and the biggest conflict the world had ever seen were a spent force. Despite the fact that the GWR could have probably survived this, the other three railway companies were not as fortunate and the decision was taken to nationalise the railways. Hawksworth carried on in his role for the first two years of the nationalised industry from 1948 but he finally retired in December 1949 after eight years in the job. A short reign compared to the rest of the 20th century incumbents.**

15XX class pannier tank No 1507 at Old Oak Common in 1962. Photograph by Mike Peart

He had taken the traditional Chief Engineer’s interest in local town matters and had a wide variety of titles under which he served Swindon. He had been a town councillor, a local magistrate and even a building society director. As a thank you for his work on and out of the works, he became a freeman of Swindon in 1960. Although he never married, he clearly kept busy in his long retirement. The last of the GWR’s Chief Mechanical Engineers finally passed away in Swindon on 13 July 1976 at the grand old age of 92. His ashes were interred at St Mark’s Church, where they rest to this day.

County class rebuild No 1014 at Didcot on 22 April 2023

Had the war not happened, had nationalisation not happened, it is intriguing to speculate where Hawksworth would have taken GWR locomotive design. Would a Great Western version of the LMS Duchess class Pacifics have occurred? Would modernisation have happened faster? No idea personally, but it’s fun to guess! If you want to see Hawksworth’s legacy, simply visit the preserved lines of the British Isles. There are 12 examples of his locomotives preserved over 5 different classes. In fact, the only one of his classes not to have a representative in preservation is the 10XX County class 4-6-0. Well, for the minute at least ….

Bonus mini blog!

Many thanks to Drawings Kev for the input into this one. I asked him if the archive might have just a little something penned by Hawksworth himself? Oh me of little faith! I’ve paraphrased his email, as the insight into the collection from its keeper is always most welcome. It was quite something for a nerd like me to see the original general arrangement drawings for No. 111 The Great Bear popping up in my inbox .… Over to Kev.

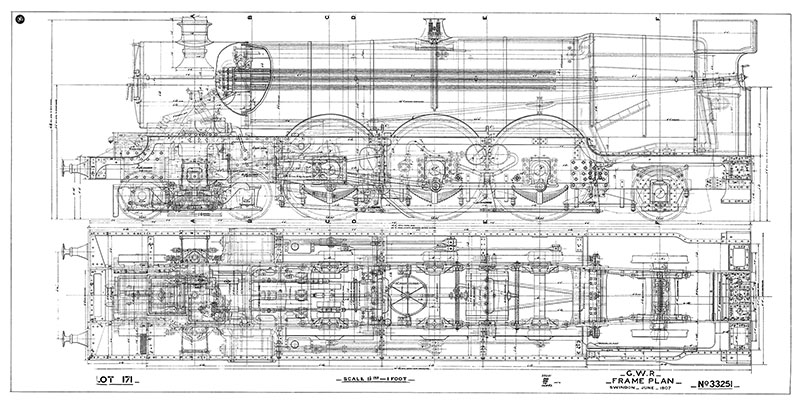

Wikipedia says;- Hawksworth was one of Churchward's "Bright Young Men", and was involved in his revolutionary designs including the general arrangement drawings for The Great Bear. This is that drawing, No 33251 ….

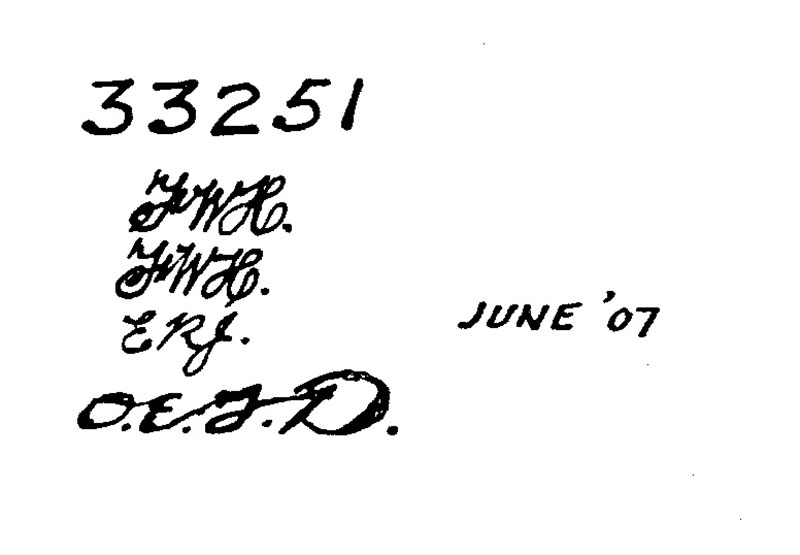

.… and the signature box of No 33251 which I've zoomed in on.

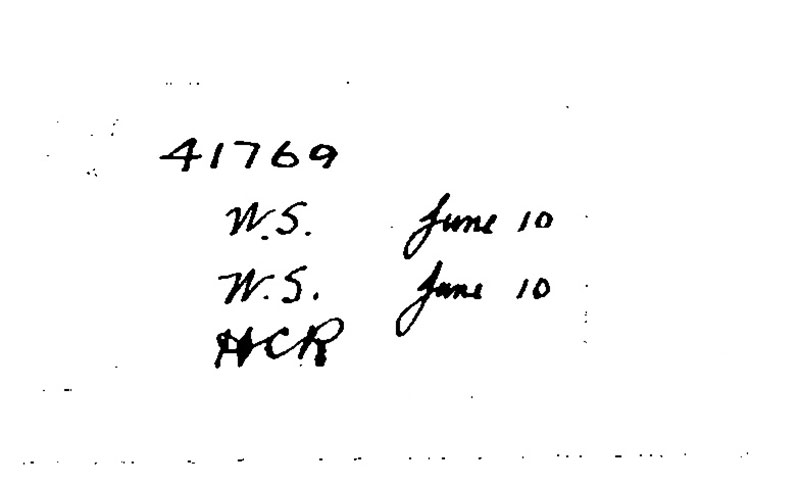

Also one of his contemporaries – W Stanier. From drawing No 41769 of 1910

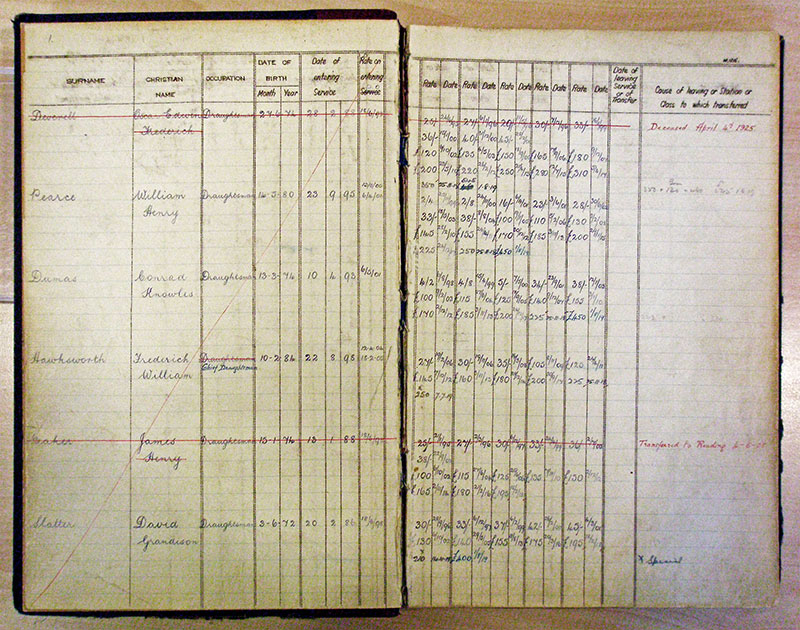

Two pages of the drawing office staff ledger, look for the fourth entry down. It only goes up to 1919 but is interesting.

*See my series of blogs called ‘Halls of the Mighty’ for more details.

**For the record, they weren’t all called Chief Mechanical engineer – the title was first used for Churchward in 1916. Before that they were Locomotive Superintendent. However, for chief engineers of some description, acting in the top job in the 20th Century, their tenures were as follows:

1. William Dean 1877-1902 (25 years’ service)

2. George Jackson Churchward 1902-1921 (19 years’ service)

3. Charles Benjamin Collett 1922-1941 (19 years’ service)

4. Frederick William Hawksworth 1941-1947 (GWR) and 1948-1949 (BR Western Region) (8 years’ service)

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.