Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - June 2023 - Going Loco - June 2023

Going Loco - June 2023

FRIDAY 30 JUNE

Making a R.O.D. for My Own Back?

One from the history books today! The exploits of our very own Churchward Mogul No 5322 in World War One have been the subject of a blog for Going Loco before, and we have chatted about other engines that served in the conflict too. There were only around 20 of the Great Western Railway Moguls that went to the Western Front. The mainstay of the service was done by a locomotive created for the Great Central Railway (GCR).

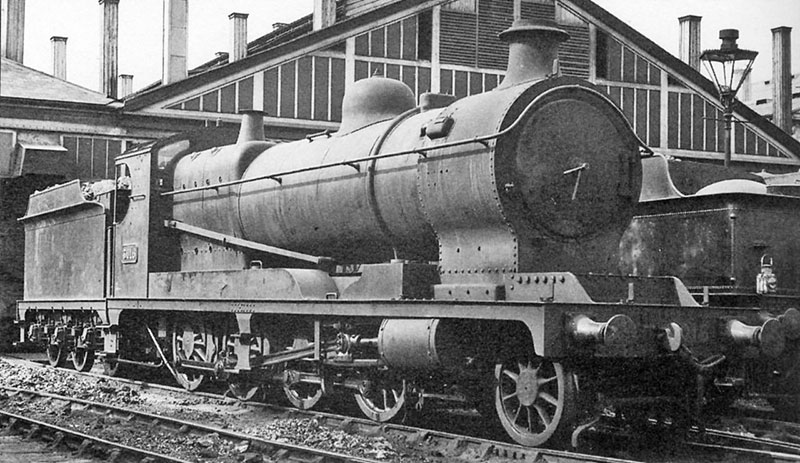

ROD No 3016 outside Swindon engine shed in the 1930s. Great Western Trust photograph

The 8K class 2-8-0 locomotive was designed by John G Robinson. He became the chief mechanical engineer of the GCR.in 1900 and his tenure lasted until 1922. During this time, Churchward on the GWR had developed the 28XX class 2-8-0 – the first of its kind in the UK – in 1903. The 2-8-0 shape was to become a standard for heavy freight locomotives in the UK and the GCR were an early adopter. The first 8K emerged from the company’s workshops at Gorton in 1911.

Like her GWR counterpart, the 8K became an instant success and was very well regarded by the railway. Up until June 1914 a grand total of 126 had been completed. Of course, world events were to overtake normality in 1914. The Great War had begun. The general manager of the GCR was a gentlemen by the name of Sir Sam Fay. He was a railway employee of long standing and had worked his way up from being a junior clerk on the London & South Western Railway at the age of 15. He became an important figure in the management of transport nationwide during the war and he was in a position to suggest to the Ministry of Munitions that Robinson’s 8K should become the standard locomotive for war work.

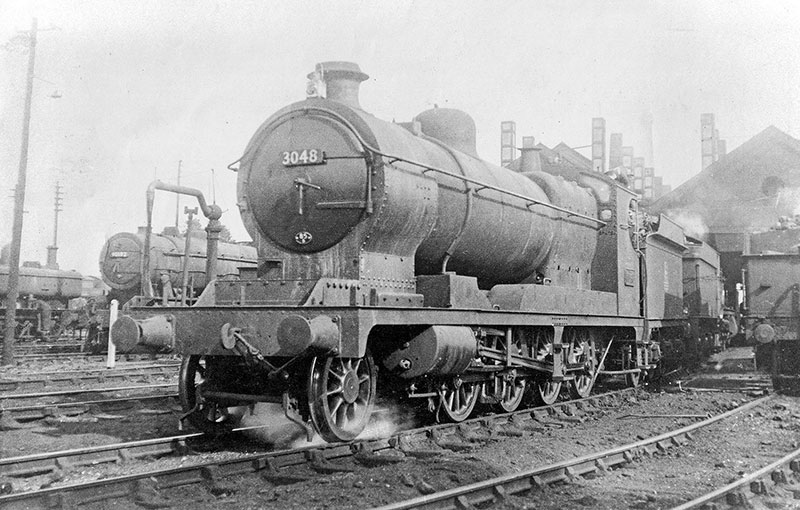

ROD No 3048 of Gloucester engine shed. Great Western Trust photograph

Between 1917 and 1919 around 500 were built for the Railway Operating Division (ROD). Many of them went to the Western Front and served there. These engines were essentially the same as their GCR. sisters except for a few key items. Firstly, being expected to run on the railway systems of both the UK and the continent, they had vacuum and air brake equipment. This is made obvious by the large air pump that you see bolted to the side of the smokebox. They also used steel instead of the more usual* copper inner firebox, thus making a saving in scarce materials during war.

They were built by a number of private locomotive contractors and, with the GCR units as well**, totalled 666 engines. Those that went to France were slowly returned after the Armistice in 1918 and were put to use at home due to the huge backlog of locomotive maintenance that had built up. They were seen as a stop-gap measure, and they could be used until the railways had caught up and made good their existing fleets. This is where the title of this blog becomes clear as in talking about these engines, it does become a bit complicated …

ROD No 3042 on a southbound goods train at Naas crossing south of Gloucester on 13 August 1949. The locomotive had been built in 1917 and worked in France as ROD No 1826. Hired to the GWR in 1919 as No 3091, then stored until 1925 when she became GWR No 3042. She was withdrawn in July 1956. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

The reason that we have an interest in this class is because they served with the GWR. There were numerous batches that worked with the Western at various times and in various capacities. The first batch that became the property of the GWR were 20 that were bought from the government in 1919. They were numbered 3000 to 3019. Further operational requirements meant that another 84 were hired in July of the same year. These were temporarily numbered 3020-3099 and interestingly the last four got Nos 6000-6003. The numbers later reused for the King class!

So, those that were bought were kept and those that were hired were all returned to the government in 1922. But the GWR found that it still needed the locomotives, so it bought another 80 in 1925. Some of these engines were ones that had been hired to them earlier and some were not. Despite this they were all renumbered 3020 to 3099, regardless of any previous number they carried. Confusing enough so far? It’s going to get worse ….

ROD No 3042 in process of being repainted at Swindon Works on 22 February 1953. A fine collection of chimneys in the foreground. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

Those engines bought in 1925 were by this time in a wide variety of conditions from not bad to really quite awful. So what was needed was a rethink. So, here we go again …. The idea was to end up with 50 good examples of the class to remain in service. The other 50 were deemed disposable. The first 50 were made up of Nos. 3000-3019 (the original GWR purchase)*** and the 30 best of the 80 just acquired. These were re-renumbered to 3020-3049. This group of 50 was treated to a major makeover. Copper fireboxes were installed as longevity was now an issue. Standard GWR fittings were applied wherever possible and they received green paint and brass safety valve covers to boot. The last of this 50 was updated in 1929.

The other 50 were not so fortunate. They were re-renumbered to become 3050-3099 and they were simply patched up as best they could be, painted in the ROD black and sent out into the world to work. When they failed, as they inevitably would do, they were written off and scrapped. From the re-sorting in 1926/1927, they didn’t last long. They were extinct by 1931. So that’s that then?

Err, no ….

A ROD tender at Swindon Works in 1962, still showing GWR lettering through the worn paintwork. Photograph by Mike Peart

1939 happened as did the Nazi invasion of various European states and the continent descended into war again. Needless to say that these engines served once again and there isn’t the space here to recount all their exploits. What we need – said the GWR at the time – is a whole bunch more heavy freight locomotives. We can build some but we think that the London & North Eastern Railway (LNER) has some that are very similar to those 30XX class things we have. Perhaps we can borrow some of those too?

The National Collection’s GCR 04 No 63601 on display at Doncaster on 27 July 2003. Creative Commons photograph by Our Phellap

Needless to say that 30 of what was known to the LNER by then as the class 04 were duly loaned to the GWR from November 1940 until the last one went home in early 1943. They retained their LNER numbers for the duration but the amazing thing is that no less that three of them had been hired by the GWR way back in 1919! After the war ended, a slow decline of these old soldiers was inevitable. 46 of them made it through to Nationalisation in 1948. The last five of them struggling on until the late 1950s. This early withdrawal date unfortunately meant that none of the GWR machines made it into preservation.

J & A Brown ROD No 23 at Hexham New South Wales in June 1973. Creative Commons photograph

It is a real shame that they went before the preservation movement really got going as they would have been a fantastic choice. Their connection with the Great War would have made them a genuinely interesting addition to complement our very own No 5322. A genuine GCR Robinson 8K, No 102, built in 1911, has survived as part of the National Collection. In the tradition of this design of engines, she was renumbered several times in her life! The LNER renumbered her to 5102 in June 1925, then re-renumbered her to 3509 in April 1946, re-re-renumbered her to 3601 in February 1947 and in the end, British Railways re-re-re-renumbered her to 63601 in September 1949! Of the genuine ROD 2-8-0s, there are three still in existence in far-flung Australia****. None are operational and only one is restored for exhibition. Let’s hope that one day, fortune favours these old soldiers and grants them another chance to steam again.

*For British locomotives at least.

**There was also a batch of 19 slightly updated engines built which had the Class designation 8M.

***Presumably Swindon was confident in the condition of these engines as they had been looking after them pretty much from new.

****Thirteen of them were purchased by J & A Brown to work on the Richmond Vale Railway. Three are preserved - ROD Nos 1984, 2003 and 2004. The last two served on the Western Front.

FRIDAY 23 JUNE

Four Castles – The Tyseley Job

The team at Didcot that helped organise and run the Four Castles event at Didcot were very fortunate in being kindly invited by Vintage Trains and Tyseley Locomotive Works to attend the Four Castles event at their home base. We met up at Didcot and were chauffeured to Tyseley by our resident boilersmith, loco engineer and Going Loco fact checker Ali – many thanks to him for his extra involvement in the day.

A likely looking lot awaiting transport… (Photo: Karl Buckingham)

So what did we see when we got there?* Well, we were confronted with this magnificent spectacle:

Photo: Edward Bull

Photo: Edward Bull

Four Castles and a Hall gathered around the former roundhouse turntable! We have talked about three of the four Castles before but the fourth has eluded us thus far!

Photo: Karl Buckingham

No 5080 Defiant was completed in May 1939, originally carrying the name Ogmore Castle** but was renamed in 1941 to commemorate one of the aircraft types flown in the Battle of Britain. She worked from several Welsh sheds as well as Old Oak Common (London Paddington) and Swindon. She was withdrawn from Llanelli shed in April 1963 and was deposited in Barry Scrapyard from where she was rescued by Tyseley Locomotive Works in August 1974 and her restoration to running order was completed by July 1987. She ran over both the main line and preserved railways until the end of her boiler certification in 1997. She was put on display at the Buckinghamshire Railway Centre until May 2017 when she returned to her home at Tyseley. There is currently a fund called the Defiant Club which is raising money to overhaul the engine and put her back on the main line.

Photo: Author

Tyseley added a little something different to their event by doing a three Castle Cavalcade. Sadly, not easy to photograph but it was impressive up close! Need a little something to pull your passenger train? How about somewhere around 95,000lbs tractive effort?!

The whole area and the workshop is an absolute treasure trove of locomotives.

Photo: Edward Bull

In this photo alone, left to right, we have the unique BR 8P Pacific No 71000 Duke of Gloucester. This loco is having a very thorough overhaul and a number of upgrades to see her return to operation. In the middle we can see the new build Holden F5 tank engine. To the right is the boiler of Hall class No 4936 Kinlet Hall. You can’t fault the variety!

Photo: Edward Bull

Here we can see the rest of Kinlet Hall with a brand new GWR tender tank in front of her. There were superheater elements everywhere (the pipes on the ground) as a large batch was being constructed. Once you have the tools, materials and drawings out, you may as well do all the jobs you need to do with them I guess!

Photo: Author

No 7822 Foxcote Manor was in the works for repairs. There are a few of these machines in the works at the moment for overhaul and rebuilding. Clearly a very useful type in preservation. Just in front are the frames of the very interesting Midland Railway ‘Half Cab’ 0-6-0T No 41708, which has just had her restoration to working order started.

Photo: Author

The new Grange class locomotive No 6880 Betton Grange was also on display. The donor loco No 5952 Cogan Hall was outside. The long term aim once the Grange is done is to restore No 5952 and replicate the parts used by the Grange such as the bogie and tender.

Photo: Author

Photo: Leigh Drew

The treasures kept on coming. LMS 4-6-0 Jubilee No 5593 Kolhapur is stashed away for the future. One day …There were panniers, small prairies, and so on and so on. All in all we had a brilliant day. Many thanks to everyone at Tyseley who invited us, made us feel so welcome and gave us the behind-the-scenes tour and also thanks to everyone at Didcot that made it all happen. We hope you enjoyed sharing the visit with us!

*This has started to feel a bit like one of those “what I did on my holidays” writing exercises we all did at primary school …

**This was the second of no less than four engines that carried that name. Each one being successively renamed. For the record:

No 5056 became Earl of Powis.

No 5080 became Defiant.

No 7007 became Great Western.

No 7035 is where the name finally rested.

FRIDAY 16 JUNE

The Heavy Tank Squad - Part 4: The Final Frontier?

We have pretty much looked at all that the service history of the eight-coupled heavy freight tank locomotives has to offer (in this brief blog format at least!). There is however a remaining legacy in the society’s collection and that is No 7202.

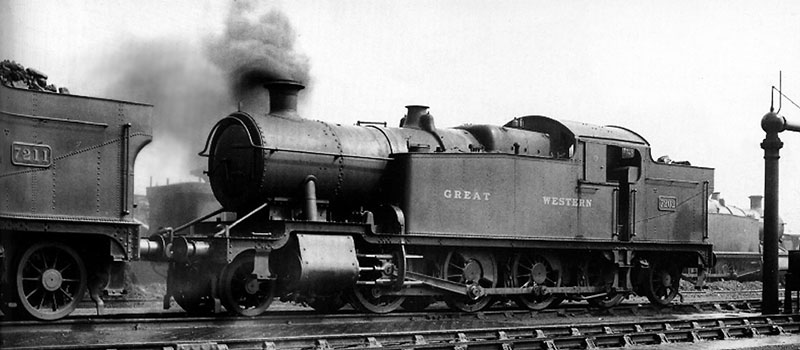

7202 in 1937

This locomotive and her restoration has been something of an epic. The team that look after her have always referred to it as the ‘rolling 5 year project’. This hides the truth that it has been in progress on and off for the last 30 years, making it by far the longest running scrapyard restoration in the society’s history. It’s not quite finished yet either …

The Heavy Freight Mob at the launch in 1986 of their first locomotive, No 3822

It has to be said, however, that there has been a fair bit that the team has done in the meantime. They have also looked after the other heavy freight machine in the collection, 2884 class 2-8-0 No 3822. This has also been restored from scrap condition and gone through two boiler certifications. The team has also ensured that the engine has funds through the running of the occasional pop-up bar on site, including the famous Black Python, and tried to do as much of the work themselves to reduce costs to a minimum. I guess under those terms, the time span is understandable!

An enjoyable and effective method of fundraising for 7202, the Black Python bar

The philosophy of the overhaul has been to return the engine to as close to her ‘as built*’ state as possible. The engine is being restored using the same techniques and methods as the engineers and craftsmen at Swindon Works did back in the 1930s. The engine was originally built as a 5205 class 2-8-0T No 5277 in 1930 and her conversion to 72XX class 2-8-2T was completed in 1934. The engine entered Barry Scrapyard directly from service in 1964, as her last shed was indeed Barry! Clearly delivery wasn’t difficult. The engine stood in the yard for ten years as she was purchased for preservation in 1973 and moved to Didcot in 1974.

Fitting coupling rods onto 7202

Whilst engines from the scrapyard at this time were still relatively complete, there were a few exceptions. While the difficult-to-extract copper inner firebox and bearings were still there, there were a lot of non-ferrous (metals like brass and copper) components that were easy to remove and had been taken off and melted down before the society got anywhere near it. This was always the first challenge of a Barry restoration.

7202’s number stamped on the motion parts

The second challenge was that these engines had been treated as disposable towards the end of their lives. Repairs and maintenance that were once done as a matter of course in the steam era was deferred, as there was little point on spending money on something you were throwing away in the march towards modernisation. This certainly didn’t mean that all the engines in the yard were absolutely run into the ground – overhauling steam engines carried on surprisingly late – but some were pretty rough by the time they got there.

Riveting the smokebox door

The final challenge was the very location of the scrapyard. Barry is a coastal town. With the coast comes the sea, and with the sea comes salt air. It doesn’t take long for it to start corroding steel and iron and tuning it back into iron oxide. If you look at locos that have had the ‘Seaside Retirement Home for Old Engines’ treatment, you can actually tell which way round they were facing in the scrapyard. The metal that faced seaward is always pitted more heavily than that facing landward. The longer an engine was in there the more damage this did and also, the more opportunity for components to be removed and sold to other restoration projects.

A fabricated balance pipe between a side tank (left) and the tank under the bunker (right)

Since the overhaul began, the locomotive has been stripped down to its basic components. The mechanical components were all in need of attention. It was best described as steam engineers often do – as a bit tired … The whole of the mechanical systems of the engine were examined and repaired. The axle boxes, rod bearings, motion and all the other moving parts were brought back to their original tolerances or replaced. The vacuum pump, part of the braking system, was found to be hugely misaligned and took a while to bring true again. This misalignment had caused a great deal of wear in the pump rod and a new one was manufactured.

The woodwork on the fireman’s side of the cab

The steel platework of the engine was also in very poor condition. A great deal of new metal has been added to both of the side tanks. They were quite corroded and certainly wouldn’t have been much good at holding water as they were! Along with the bunker, they were rebuilt exactly as Swindon produced them, reusing as much of the original as possible. The quest for originality here went down to the balance pipes. There is a pipe, each side, that goes from the water tank alongside the boiler to the water tank under the bunker. The idea being that it allows the water level to go down at the same rate in all the tanks at the same as it is fed into the boiler, preventing the engine being hugely unbalanced. The easy thing to do here it to use round pipe but the originals were a very complex fabricated part. It’s the same on the large prairie 2-6-2s. Needless to say, brand new versions now adorn the space behind the cab steps.

Having successfully removed the original front tubeplate, the team find a new place to relax

The cab roof was restored and new brass window surrounds were cast and fitted. The non-ferrous fittings of course were mostly long gone and needed remanufacturing and machining. The last of these to be sourced and fitted will be the injectors. The boiler cladding has also been renewed with new crinolines being made as the last set of cladding – now long gone – would have been supported by asbestos cement. Needless to say, this is a step towards authenticity that the team won’t be taking …

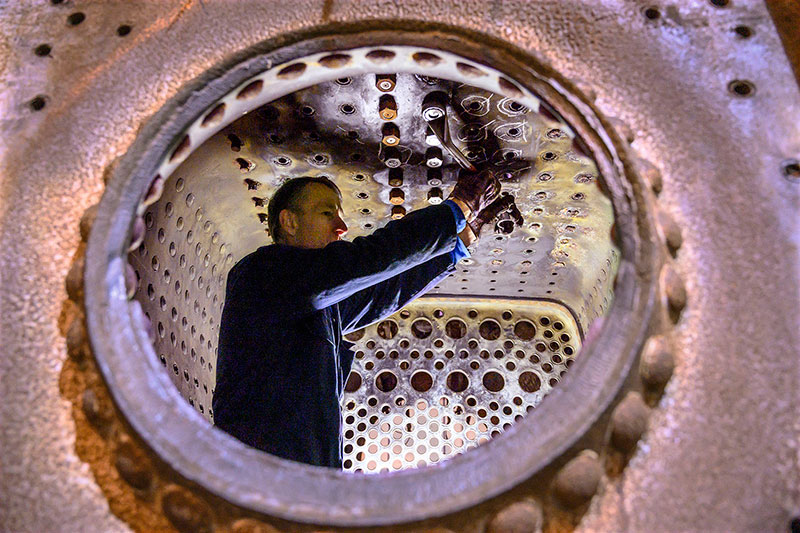

Tightening the bolts on crown stays inside the firebox

So how are the team doing? Well, the vast majority of the work on the frames and platework is finished. The cylinder drain cocks and the operating linkage are being finished off, as is the cladding for the main steam pipes. The woodwork that goes in the cab is also finished too as are the water distribution trays that sit in the boiler under the clack valves. The gauge frame that shows the water level in the boiler is also nearing completion. Which just leaves the boiler. Our contractors are forging ahead with this as well as working on No 1363.**

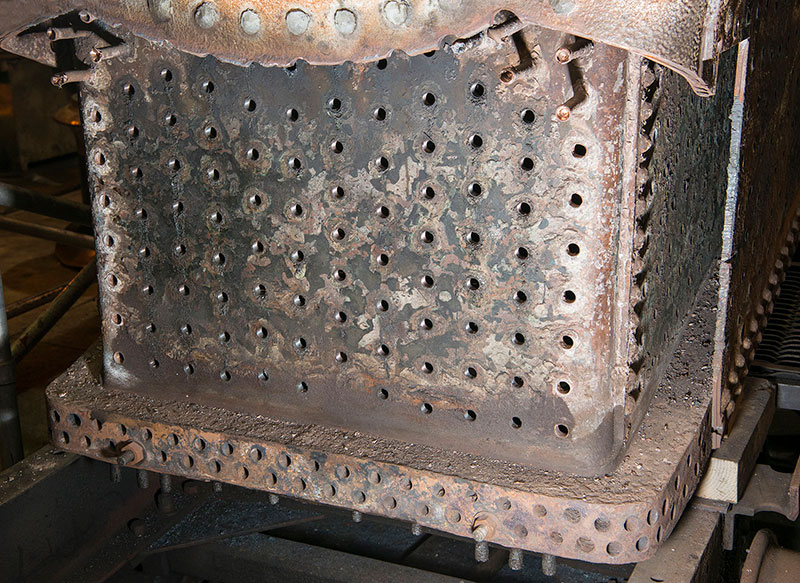

Reaming the crown stay holes on the outer firebox wrapper

7202’s boiler was in fairly poor condition and has a lot of continuing repairs to its steel plates. The front tube plate has been removed and a replacement made. It needs a new section to the lower front, sides and rear of the outer firebox. It has had all new crown stays over the top of the firebox and will need a great deal of them down the sides where the new metal will be added. The team has the new sections of boiler plate ready to replace the sections removed. This will also need all of the rivets in the foundation ring at the bottom of the firebox to be replaced too.

A large part of outer firebox wrapper has been removed for replacement

It’s been quite the odyssey, and it is the longest running overhaul in society history. It is going to end soon though. There are two other 72XX 2-8-2Ts that are in preservation and it will be interesting to see which one makes the final leap back into the land of the living first. Which one will it be? Wait and see …

The new firebox throatplate sheet being shaped, in preparation for fitting

* Or possibly ‘as converted state’. See last week’s blog for detail.

** Sounds like another upda

FRIDAY 9 JUNE

The Heavy Tank Squad - Part 3

We got to the end of the production of the heavy freight 2-8-0s in 1940 last time, but we have to back track a bit in order to explain the occurrence of what was to become the largest tank engine design in preservation in the UK.

There were five batches of the 2-8-0 tanks built: 10 in 1923, 10 in 1924, 30 between 1925 and 1926, another 20 in 1930 and finally, the last 10 in 1940. The timings of these builds was sadly in concert with some fairly momentous events in world history. The 1930 batch were particularly hard hit by events. The Great Depression was a global economic turndown that was triggered by a terrific crash in prices on the Wall Street stock market of New York. The ripples of this rolled out worldwide.

This became the longest and deepest economic depression of the 20th century. There were huge implications for companies worldwide but we, in this blog are of course interested in the Great Western Railway. Those new-born 52XXs were in some ways almost still born. The depression had absolutely hammered the coal industry in Wales.

Exchange traffic in October 1946 for the Southern Railway at Reading, with No 7252’s train switching from the relief to main line prior to running onto Southern metals east of the station. Photograph by John Ashman

In the face of a renewals programme where the old 0-6-2 tank engines of the amalgamated Welsh railways were being replaced by the GWR engines, the coal traffic fell dramatically. No sales of coal meant no coal mines which meant no coal traffic which meant no need for all these shiny new locomotives. These pieces of engineering excellence were being built, tested, run in and immediately put into storage. There was no work for them.

So what was the problem? The very reason that made them so suitable for the tough runs up and down the Welsh Valleys was the reason that they were hamstrung. It wasn’t their power – they had that on spades – it was their ability to project that power. The tight clearances had restricted their coal and water capacity. They just couldn’t go long enough distances to justify their use on the majority of freight services outside their natural habitat. The existing working members of the fleet displaced by the depression had already taken those roles that existed.

A 2-8-2T working hard on Dainton bank with a train of stone from Stoneycombe quarry in Devon. Photograph by John Ashman

Clearly, having a brand new and expensive asset sat around, doing nothing in the middle of an economic downturn, is not a great idea. So, what do you do? Well, those big beasts were going to have to wear a bigger backpack! In the greatest tradition of make do and mend allied with cut and shut technology, the engineers at Swindon got to work. The first thing they did to No 5275 was to remove the rear of the engine.

The buffer beam and its supports, the pipework, drag box* and the rear sheet of the bunker came off and were put to one side. Having cleared the decks metaphorically, they the set about adding 4 feet of extra frames to the rear of the engine. Below this was added an extra set of carrying wheels, turning her into a 2-8-2 or Mikado tank engine. This was the only class of tank engine in the UK to ever carry this wheel arrangement.

No 7221 at Severn Tunnel Junction engine shed on 15 April 1951. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

Above the frames, the backpack was riveted in place. If you look at a great many GWR tank engines, you will see that there is a diagonal line of rivets about two thirds of the way down the bunker. On top is a slope on which the coal sits. The idea being that it will slide towards the fireman. Below that is a third water tank. The two main side tanks are connected to this by balance pipes – one at each front corner of the bunker tank. This allows the water to go down equally in all the tanks at once. A full tank on one side and empty on the other could cause all sorts of problems – especially with weight distribution. The tank and bunker were thus simply extended.

On this first engine – to be known henceforth as No 7200 – as built the coal capacity went up from 4 to 6 tons and the water from 1,800 gallons to 2,400 gallons. Quite the increase! Well, it was after the rear of the locomotive was returned to its rightful place …

2-6-2T No 4152 piloting a 72XX class 2-8-2T with a coal train from South Wales, emerging from Ableton Lane Tunnel, just east of the Severn Tunnel. Photograph by P M Alexander

The success of this machine resulted in three batches of these conversions being undertaken. The first, that includes Didcot’s example, was done between August and November 1934. This was a further 19 engines. The realisation of the genuine usefulness of these engines lead to a further 20 being converted between August 1935 and February 1936. The final batch, converted between August 1937 to December 1939 took the total to 54 engines. This third batch of engines was slightly different in that it was made up of 42XX class engines and introduced the ‘coal scuttle’ bunker arrangement.

2-8-2T No 7226 of Swansea East Dock shed about to return home after a major overhaul at Swindon Works in 1962. Hall class No 5917 Westminster Hall is just behind. Photograph by Mike Peart

This was an attempt to allow the coal to flow down to the fireman a bit easier and is easily seen (nerd points incoming!) by a higher line of diagonal rivets on the side of the bunker. This had two effects. It reduced the coal capacity to 5 tons and increased the water capacity to 2,700 gallons. Some earlier conversions were retro fitted with this arrangement and the class pioneer, No 7200 (now preserved at the Buckinghamshire Railway Centre) was one of those so treated.

Several of the now ‘missing’ slots in the 52XX number series were filled with the new build 2-8-0Ts eventually, so the numbering gets a little confusing. For example, No. 5264 was built as part of the 1925/1926 batch of 52XXs. This engine was converted to become the now preserved 2-8-2T No 7229 (East Lancashire Railway) and a second No 5264 was built as part of the final batch of 52XX 2-8-0Ts in 1940. Confused? If you weren’t before, you are now!

Oxford-based No 7239 is seen on shed at Southall in 1962. This loco was a rebuild of No 5274 in 1936. We didn’t see very many of this class so near to London as the 28XX and 38XX class usually worked the heavier coal and freight trains. Note the diagonal line of rivets on the coal bunker is above the numberplate, signifying this is a ‘coal scuttle’ bunker (see nerd points in the blog). Photograph by Mike Peart

The only slight fly in this particularly well-crafted ointment was that the extra length of these engines saw them being what is often referred to somewhat euphemistically as a little ‘curve shy’. Translated, it meant that they came off the track if the corners became a bit too tight! So those engines converted were banned from certain places on the network so that the breakdown crews were kept less busy …

No 7248 at Swansea East Dock engine shed on 13 April 1962. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

This limitation notwithstanding, the conversions were put to great use wherever their immense weight of 92 tons 12 cwt was permitted. They did a lot of work on iron ore trains as well as the more general freight work. Some still found work in Wales and our example is one of these. No 5277 was built as part of the 1930 batch of 52XX 2-8-0Ts and as a result was one of those put straight into store from new. She was the third conversion to 2-8-2T configuration and as a result gained the new number 7202. Entering service proper for the first time in September 1934, she worked out of Ebbw Junction Shed. Although she wandered about a bit, her last posting was at Barry Shed. Very convenient for a local scrapyard … She entered the yard to join three of her sisters in 1964.

No 7202 at Didcot Railway Centre, showing off the diagonal rivets on the side of the bunker which are positioned below the numberplate, signifying this is the original design with less water capacity, but more coal, than the ‘coal scuttle’ modification (see nerd points in the blog)

Sadly, the fourth, No 7226, was one of the locomotives actually cut up at Barry. She went in 1965. The other three held their ground however and all have now found homes. No 7202 reached sanctuary at Didcot in 1974 and has been an on again, off again, project for about 30 years. It is now very much on again and the final push isn’t that far off now. When a 72XX does finally steam in the 21st century, it will close a circle somewhat. The 72XX is the only class of steam locomotive that was present at Barry that has yet to steam in preservation. I guess the race is on …

Next time I will get the latest news on how No 7202 is coming along. From what I’ve seen recently, just like her former owner, we’re getting there!

* The bit where the coupling hook goes into. As you might imagine, there’s a fair bit of strengthening that goes on here …

FRIDAY 2 JUNE

The Pioneer's Progress – Part 8

We are going to interrupt your regularly scheduled eight-coupled tank engine blog with a news flash! My good friend Phil who looks after the overhaul of our first ever locomotive – 14XX class 0-4-2 No. 1466 – has provided us with an update and I didn’t want to keep you from it! So, take it away Phil!

1466 on 11 October 1969, standing next to Wantage Tramway No.5 Shannon - The first time the GWS steamed Shanon, presumably the first time since 1945 - Frank Dumbleton

Thanks Drew! - Well, its been quite a while since my last blog entry for you all and its certainly been an interesting and (quite frankly) testing time. Yet, as always work still continues at a steady rate despite the challenges we have faced. Ryan and team at West Somerset Restoration (WSR) and come to think of it, various British Engineering Services (BES - our boiler inspectors) inspectors in-between, have soldiered on regardless!

So where do I start? With the elephant in the room? Many of us who are fortunate enough to work on steam locomotives will know they aren't quite the simplest of things and at times, can cause a great deal of stress – in my last entry, I mentioned that we had ordered a new copper doorplate and tubeplate for the inner firebox. Thankfully the door plate landed with us earlier this year and Ryan and his team have been making good headway in getting it ready for fitting. The new tubeplate, however, had other ideas. Firstly, there was a delay in delivery to South Devon Railway Engineering (SDRE) as the shipments of platework for some reason got split up from metal foundry/supplier and then later on faced further delays, due to an outside machining company who unfortunately, er, ‘let us down’ shall we say …

Thankfully after some time, persistence and many many phone calls later, another machining company with the capability to hold and machine such a large and thick piece of copper plate was found and the plate sent off for machining to profile. The outcome (thank goodness), being that the plate has been machined to size and has arrived back at SDRE. It's now set to be pressed to form and to have the tube nest drilled within the next couple of weeks. So, delivery to the West Somerset Railway is now, thankfully, somewhat imminent …

Anyway, onto more of the progress. In between the inordinate amount of time spent on the above, there has been a vast plethora of other ongoing work. To start with, a further inspection of the palm stay brackets found them to have been rather corroded away over the years. It was felt that it was best to get a new set made, even more so given the easy access we currently have to the inside of the boiler.

New palm stay brackets being machined & The finished product, with an old one next to it for comparison

Along with that; The safety valve assembly (a crucial part of the boiler) has been dismantled for a thorough inspection by us and BES. Whilst the majority of its components are in very good condition, it will require 4 new pillars and 2 new spindles due to the components being heavily pitted due to sitting in water that has collected and caused corrosion over the years.

The safety valve dismantled & cleaned up & The 4 old pillars and 2 spindles that are to be replaced

The regulator tubes that stretch the length of the boiler have been hydraulic tested on the latest inspection by BES. The rear section received a new end due to damage that occurred when it was originally removed. This section passed with no leaks at 250psi. The hydraulic test of the other section however wasn’t as successful and a small crack was found on a seam. This is of course why we do these tests. The good news is that it should just need to be thoroughly cleaned and brazed to reseal the tube seam – quite straight forward really.

The new end fitted to the rear section, The first section passing at 250psi & The rear section leaking due to a crack found on the outer seam

Whilst that was all going on, work on getting the copper firebox assembly back together has started; whilst we await the somewhat elusive tubeplate, the door plate has been thoroughly marked out and trial fitting in the outer-wrapper has occurred. It has to be said, it fits very nicely.

The new copper doorplate fitting nicely in the outer wrapper, Matt Healey marking out all the various rivet and stay holes on the doorplate & The copper firebox taking shape

Boiler cladding or what was known by the GWR as ‘cleating’ has also been on our radar. Fortunately, the boiler cladding on 1466 was in quite good condition to begin with and therefore hasn't required a huge amount of work. There was of course the odd area here and there, that required some work, but overall, it was rather good and after a fine sand blast and some painting by Harry, it's come up really well.

Various stages of the restoration of 1466s boiler cladding

So where now? Well, we needed a new blower ring. A new casting was sourced from our own stores at Didcot and sent off for machining. The looks I got lugging a rather large lump of metal off site on a sack truck and through Didcot Parkway station to the car were great! It led to a few puzzled looks amongst commuters. Oh, the joys of no direct road access! (Thankfully the new site entrance ramp, work on which which is soon to be started, will make bringing and taking parts on and off our site much easier – when required). The copper firebox is starting to take shape nicely, the front regulator tube is being repaired currently to be hydraulically tested again, along with the regulator box and steam pipes at the next BES Inspection.

1466 having been moved to the other side of the shed to allow another loco onto a pit & The new blower ring casting being delivered to WSR by Phil - just needs machining

Overall, when you write a list of what's left, there doesn't seem to be that much more to go. In the grand scheme of things. There isn’t but it will take some time to finish the boiler off completely. As I mentioned earlier, steam locomotives aren’t the simplest of things and even with the small, repetitive jobs – such as riveting or fitting stays for example – it all takes time …

Amongst all this, like the best Scouts, we have tried to be prepared! The small jobs and orders keep ebbing and flowing. Materials for crown stays and copper side stays have arrived ready for machining once the final required sizes have been determined. A mass of lagging / insulation for the boiler has been delivered ready for when the time comes. And so on and so on … All that really leaves to order then is a mass of steel side stays – again, once sizes have been finalised, a set of boiler tubes and of course some paint (perhaps a nice shade of pink?*)

1466 at Exeter St Davids with a train to Dulverton - note the Horsebox behind the loco - Michael Morris

It's fair to say our little pioneer has come a long way and is finally taking shape once more – so please do watch this space. Homecoming, is on the horizon, but is inevitably just a question of time and patience … If you would like to donate to this wonderful and historically important locomotive’s overhaul, please follow the link below:

Any donations small, medium or large are always gratefully received; In a restoration such as this, every £ counts and can make a real and tangible difference to enable us to finish her overhaul.

Speaking of donations – I must say a big thank you to the many of you, who have very kindly donated to this project over the years. It has made a huge difference and without you all, we wouldn't be as far ahead as we are now. Donations play a very big and crucial part in enabling us to restore & keep these magnificent pieces of history alive, for everyone to see and enjoy.

Until next time folks…

Thanks Phil! We are so nearly there with our pioneer locomotive. We forget how significant this engine and her preservation is. Without those four schoolboys the whole Great Western Society wouldn’t exist. There wouldn’t be a home for over 20 steam locomotives, around 100 items of rolling stock, the loco shed, the buildings, the artefacts and, most importantly, the volunteers. This one act so many years ago resulted in people forming friendships that have lasted life times and to recognise that alone, returning No 1466 to traffic is a hugely important and significant gesture.

*I shouldn’t have to point this out but if there is anyone taking this the wrong way - it’s a joke. It’s going to be orange.**

**Also a joke.

Photos (unless otherwise stated) are by Phil Morrell & Harry Spencer

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.