Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - August 2023 - Going Loco - August 2023

Going Loco - August 2023

FRIDAY 25 AUGUST

The County Set - Part 3: Let Hawksworth have a go!

The previous scribblings by your blogger over the last couple of weeks have been focused in the high energy and forward looking era of Churchward’s early time in charge of the locomotives of the Great Western Railway. Where we are now is a very different situation.

No 1002 early in her career, before she was named. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

Swindon is at war. Since 1939, it has been involved in vital war work as well as the maintenance of the locomotive, carriage and wagon fleet. The ruler over this huge project has changed twice since last time. Churchward had retired in 1922 but never left the railway. He was tragically struck and killed by a train in December 1933. His successor, Charles Collett had always been a very different man to his forbear and when he lost his wife in 1923 he was devastated and never really recovered. He was a pacifist and the return to war production in 1939 made life very difficult for him to square away. He retired in 1941.

No 1002 in August 1946 with the Reading New Junction signal gantry behind her. She was named County of Berks in May 1947. Photograph by John Ashman

This left Frederick Hawksworth in charge. There was a ban on producing new express passenger locomotives during wartime. There was a speed limit of 60mph on the railways at the time in any case. Hawksworth had turned his energies initially to the updating of the excellent Hall class 4-6-0 mixed traffic machines. This he did by simplifying the design so that the large castings at the front end were reduced to just the cylinders, and the main frames went straight through from the front to the back, unlike the complex set up – sub frame with buffer beam, large cylinder castings, main frames – that most of the 20th century GWR 2-cylinder designs had.

No 1012 County of Denbigh at Reading New Junction in December 1946. Photograph by John Ashman

This was, in many ways, the epitome of how locomotive development was done at Swindon – the radical new was often eschewed in favour of the further refinement of the excellent that already existed. It also fitted in well with the wartime restrictions at Swindon. So, given that he wasn’t allowed to develop an express engine, you kind of get the feeling that he was going to make this mixed traffic engine as powerful and as near to a passenger loco as he thought he was going to get away with .…

No 1021 County of Montgomery climbing Hemerdon bank, double headed with a Hall class 4-6-0. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

The calculation that determines the tractive effort of a locomotive is based upon the diameter of the pistons, the stroke of the pistons, the working pressure of the boiler and the diameter of the wheels. If they were going to maintain the basic design of the Modified Hall class, then this restricted a little what they could do to up the power coming from the machine. The pistons were pretty close to the maximum size that the loading gauge would allow, 18½” in diameter. The stroke was also kept the same at 30” from one end of the piston travel to the other. There were a few changes to these parts but really it’s the same as far as the maths is concerned. That means we are going to have to get our power elsewhere.

No 1009 County of Carmarthen fitted with the experimental double chimney in 1954. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

The first thing that they looked at was the boiler and here they were in luck. A new type of boiler that was based on Swindon technology but came from the London, Midland and Scottish (LMS) Railway was in the works. This was a boiler designed by the team under William Stanier – a Swindon engineer who had been headhunted by the LMS. This boiler was part of the Stanier 8F 2-8-0. This is really a development of the GWR’s 28XX 2-8-0 heavy freight locomotive and was the chosen machine for standard war production much like the ROD 2-8-0s from the First World War*. Their Belpaire boiler was being built – along with the rest of the engine(!) – at Swindon and the presses for the panels of the fireboxes were just there .… Shame to let them go to waste and there was a war on you know .…

Another view of No 1009 with the experimental double chimney and shelter for staff during the test runs. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

This version of the 8F boiler had a longer barrel and didn’t have all the holes in the same places as per the LMS original. It also had its stays in a slightly different pattern so that the boiler could withstand higher pressures than the original. They were designed to be pressed to 280psi – the highest pressure that a GWR class ever used. They also had a three-row superheater from the beginning. The engines looked different from the outside too.

No 1026 County of Salop entering Shrewsbury with a stopping train from Chester on 22 June 1957. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

They took a look at the wheels. On a Modified Hall, they are 6’ in diameter. Making wheels larger reduces the tractive effort but enables the engine to potentially run at higher speeds. The Castles have driving wheels of 6’ 8½” diameter. This was too big for high tractive effort. The Kings have wheels of 6’ 6” in diameter but also have a huge reserve of steam in a 250psi boiler and 4 cylinders. What the design team did therefore was to split the difference. 6’ 3” wheels were fitted to the new engines. The bogie was the same plate framed example as found on the Modified Hall and have the same 3’ diameter wheels too.

No 1026 County of Salop at Kennington with a stopping train from Oxford. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

The big give away, if the bigger boiler wasn’t a clue, was that the splashers (covers) over the tops of the driving wheels were made in one long piece as opposed to the usual individual semi-circular ones on many other GWR types. They also used Mr Hawksworth’s all welded tender tank with slab sides. Nerd points moment – did you know that County tenders are not standard? They are 6 inches wider than the standard Hawksworth tender. This is because the cab sides on a County stick out further than they do on most other GWR tender engine types. Only once someone has said this to you do you notice that there isn’t the thin step along the edge of a cab side on a County, as there is on a Hall or a Castle. It would look funny if the sides didn’t line up!

No 1015 County of Gloucester at Challow with a stopping train. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

In any case, this was going to be the super 2 cylinder 4-6-0. It was going to out-perform the Castles – maybe even replace them. A simplified 4-6-0 with 32,580lbf. Quite the step up from the Modified Hall’s tractive effort of 28,275lbf. It was certainly more than the 31,625lbf of the Castles. Perhaps this was a great idea?

No 1013 County of Dorset double-heading a westbound express through Southall in 1962. Photograph by Mike Peart

The story goes that they were to be numbered in the 99XX series and this would have made sense as a relative of the Saints (29XX), and the Halls (49XX, 59XX, 69XX and 79XX). Apparently, the word got leaked to the railway press that this was the case and Hawksworth decided to go with the 10XX series instead. Possibly apocryphal but I like the tale! The first engines were launched into traffic without names but as the wartime conditions were slowly relaxed, post conflict, some of the names used for the 38XX County class 4-4-0s were reused.** The first being No 1000 (eventually named County of Middlesex), was completed in August 1945. She was fitted with an experimental double chimney from new. The rest of her brethren were fitted with a single chimney as built. There were thirty of them in the class, the last emerging from Swindon Works in April 1947.

No 1011 County of Chester at Bristol Temple Meads with an Exmouth to Manchester express on 10 August 1963. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

When they went into traffic they were a disappointment. It seems that the County class name curse had struck once again. Although they could ride roughly at their highest speeds, the bigger concern was that their performance was often indifferent. They seemed to relish getting stuck into the hills – make their lives difficult and they responded. However, the Counties seemed to quite literally run out of steam on long runs on the flat. They just didn’t like long periods at a constant speed. This is in stark contrast to the Castles and Kings that were capable in any situation.

The replica No 1014 County of Glamorgan taking shape at Didcot Railway Centre in April 2023

The performance of these engines was under scrutiny and experimentation for the vast majority of their lives. There are photographs of No 1000 on the test plant at Swindon in 1952. In 1954, an odd design of stovepipe double chimney was fitted to No 1009 County of Carmarthen. Test upon test was performed. This was satisfactory in its results and they all received double chimneys by the end of 1959. From 1955 onwards, the boiler pressure was reduced from 280psi to 250psi. This reduced their tractive effort to 29,090lbf but reduced the maintenance costs and hammer blow on the track. The majority of them also received 4 row superheater boilers as well, but by the time all this was completed, the end of steam was nigh.

Despite their relative modernity, the majority of the engines were withdrawn before some of the earliest Castles that they had their eye on. The first 9 went in 1962, 13 were withdrawn in 1963 and the final 8 went by the end of 1964. Their famous last stand was made by No 1011 County of Chester. This engine pulled a ‘Farewell to the Counties’ rail tour organised by the Stephenson Locomotive Society in September 1964. And with that, the railway ecosystem lost another species. That was until someone said ‘If you take that boiler off that 8F and put it on that Hall, it would look a lot like a County you know .…’ ***

If only it were that simple. It’s not like modifying stuff in OO Gauge. Still, that is a story that is yet to be finished.

* See my blog on these fascinating machines called ‘Making a R.O.D. for my own back?’ From Friday 30th June.

** Although not the Irish Counties this time - see the first part of this series for details.

*** There’s always one isn’t there?

FRIDAY 18 AUGUST

The County Set - Part 2: Churchward’s Second Try

We had a good look at the County 4-4-0 tender engines built in the early 20th century last week. Churchward and his team were at the forefront of technology at the time and were constantly experimenting with designs and thoroughly pursuing a lot of them to their logical conclusion. The larger 4-coupled design of steam engines was part of this experimentation. When you think that the 2-6-0 Mogul tender engines and 2-6-2 Prairie tank engines are very similar, it’s not surprising that from the 4-4-0 tender engines came a 4-4-2 tank engine design.

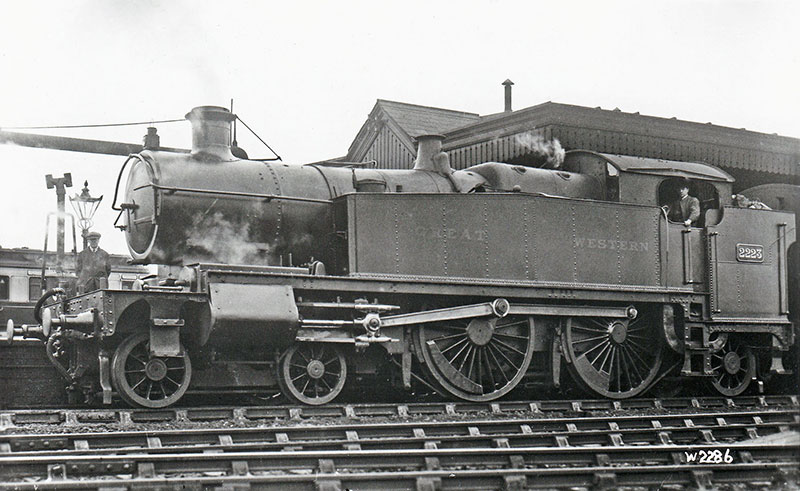

No 2226, a 4-4-2 tank as built in October 1906. The two circular extensions on top of the tank are part of the bi-directional water pick up apparatus, to direct water downwards into the tank while it is being picked up at speed. No 2226 was withdrawn in June 1934. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

There was a 4-coupled tank engine that was designed and being used for similar suburban train services already extant. It came from the era of Churchward’s predecessor, William Dean. First built in 1900, it was probably more the product of Churchward than Dean as the latter was not well and was basically seeing his way out to retirement in June 1902. This was the 3600 class and it was a 2-4-2 tank engine. 31 were produced up to 1903. The engines were fitted with quite a few mod cons including a steam powered reverser and water pick up gear for use with water troughs. This was bi-directional as this was a tank engine design. They were nicknamed ‘Birdcages’ as they possessed (for the time) a generously sized, enclosed cab.

No 3608, one of the 2-4-2T locomotives built early in the 20th century. She was built in May 1902 and withdrawn in April 1931. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

The first 2221 class, No 2221, was built in 1905 and it was of course from this engine that the breed got its name. The design was very similar to the 38XX County class but had longer frames to accommodate the coal bunker at the rear of the engine. This needed to be supported by the rear two carrying wheels. The boiler was the smaller Standard 2 version rather than the larger Standard 4 that the 38XX had. Initially, the boilers were not superheated but they all had superheaters fitted by the end of their working lives. The cylinders were the same as the 38XXs, 18” in diameter and 30” stroke as were the rest of the mechanisms used in the Counties. The driving wheels were the same too at 6’ 8½” diameter.

No 2248, built in July 1912, hauling the 6.20pm Paddington to Windsor near Dawley signal box on 4 June 1914. She was withdrawn in October 1931. Photograph in the LCGB Ken Nunn collection

The use of large cylinders with a small boiler was mitigated by the type of work it was expected to do. They were designed to accelerate fast, sprint between stations that were fairly close together and then decelerate quickly. This builds in recovery time for the fireman and the boiler. The engine isn’t expected to put out large amounts of power for long periods of time. This isn’t to say this type of operation wasn’t demanding for the fireman though .… There were three batches built, each of ten locomotives and were numbered sequentially from the prototype. The first was built between 1905 and 1906. The second from 1908 to 1909 and the final batch was built in 1912.

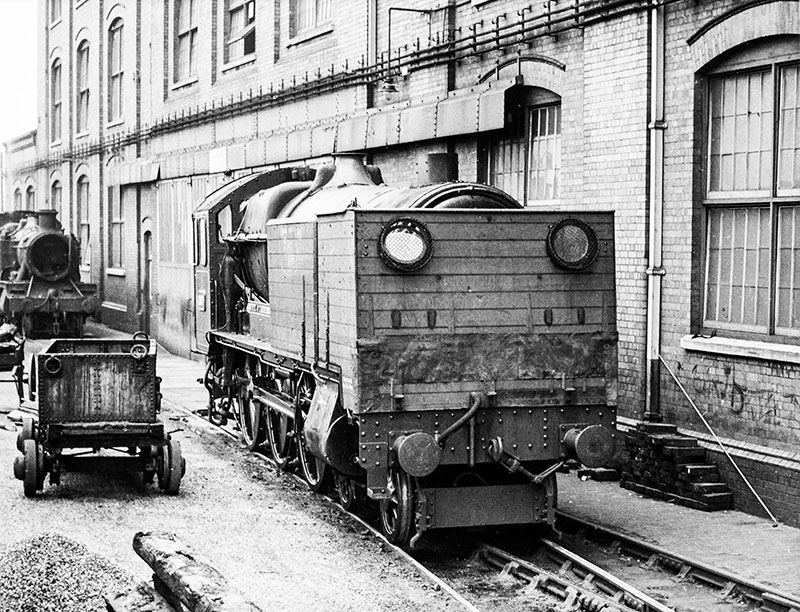

A 4-4-2 County tank at Didcot. Photograph by C E R Sherrington in the Great Western Trust collection

There were numerous detail differences between the batches. The section where the running plate drops from the high section to the lower bit where the buffer beam is at the front was given a curve in the last batch. The coal bunkers that were initially provided were sometimes updated to look like more modern designs as time went on. This increased the size and therefore the range of the engine. The reverse experiment of boiler swaps was undertaken when No 2230 was built in 1906. As No 3805 County Kerry exchanged her No 4 for a No 2 boiler for a short time, No 2230 was built with a No 4 type boiler. In both instances, they did not stay in this form for long and were converted to their respective standard types shortly afterwards.

4-4-2T No 2223 at Didcot. She was built in September 1906 and withdrawn in April 1932. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

As they were relatively new and operating on routes so fitted, the 2221s carried the new Automatic Train Control (ATC signalling system from 1908. They had brakes on their bogie wheels from new – although these were removed during the reign of Churchward’s successor, Charles Collett. The bi-directional water scoops were removed later on too. They took on the role of suburban tank engine for quite a while alongside the ‘Birdcage class’ machines, replacing them in several areas.

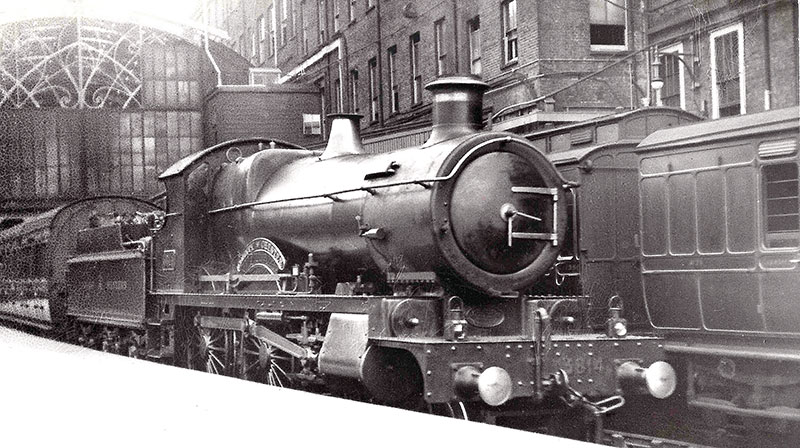

4-4-2T No 2232 at Paddington on 10 April 1928. She was built in September 1908 and withdrawn in October 1933. Photograph in the LCGB Ken Nunn collection

As they were pretty much the same mechanically as the 38XX class, you can pretty much predict the outcome of the design. They had a high tractive effort – 20,530lbf, the same as the 38XXs. They had all the same inherent issues that the County Class had too. Large masses moving about causing a very rough ride for the crew. A rough ride for the crew is a rough ride for the loco and doesn’t do it any good either.

No 2239 at Didcot engine shed in September 1934. She is in very clean condition, but was withdrawn three months later in December 1934. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

They worked in the Paddington area and accelerated the trains in and out on the commuter lines, and in this they were reasonably successful. Their time was limited, however, by the early 1930s. The issues that were inherent in the design were easily countered by Collett by using a version of the large prairie that had a higher pressure boiler. By increasing the boiler pressure of the Standard 2 boiler from 200psi to 225psi and using that to drive six 5’ 8” diameter driving wheels, the tractive effort went up to 27,300lbf. The larger wheels of the County Tank meant it couldn’t accelerate as fast and the ride on what became the 61XX class* was far superior. The first 2221 class engine was withdrawn in 1931 as the 61XXs were introduced. The last of them went in 1935. They don’t seem to have been missed .…

No 6106, built in May 1931, is one of the 2-6-2 tanks that displaced the County tanks on the London suburban services. The photograph shows her at Reading a few months before she was withdrawn in 1966 and preserved at Taplow, then at Didcot Railway Centre. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

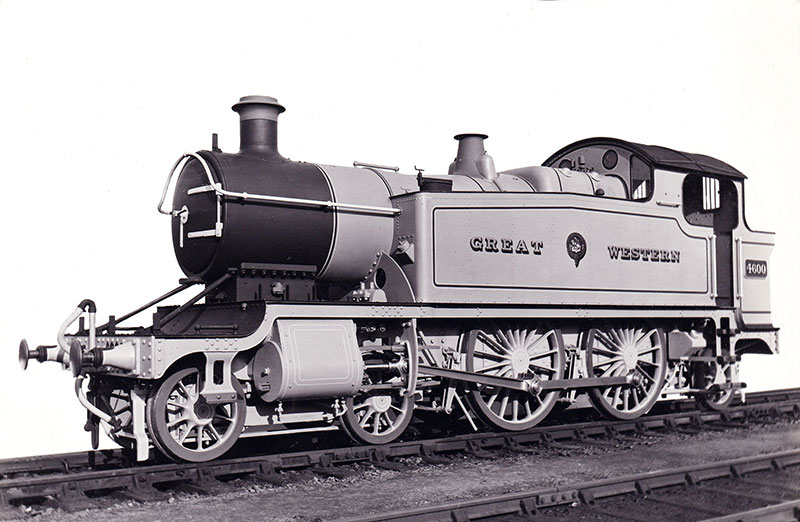

It’s worth noting here that Swindon did produce small and large 2-6-2 prairie tank engines and the same thing happened to the 4-4-2 tank engines. The ‘County Tank’ was the equivalent of the large prairie and No 4600 was the equivalent of the small prairie. The idea was to design a locomotive that would be a replacement for the smaller 2-4-0 Metro class, first built way back in 1868. It was a much smaller design and had driving wheels of 5’ 8” diameter. The issues with this design were very similar to those with the County types. Her axle weight was high and this made her unsuitable for use on smaller branch lines, unlike the small prairies. She was also not as fast as the County tanks or the large prairies. She was again a rough rider, not popular with crews. There were various modifications attempted to solve the problems but she never really met her design brief. In the end, she was the only one of the type built and was withdrawn and scrapped in July 1925.

No 4600, the small version of the 4-4-2T, built in November 1913. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

I don’t know what you call these designs – an Atlantic? An Atlantank? Who knows .… Whatever the name, they weren’t successful and represented one of those evolutionary dead ends that go nowhere. It is indicative of the era that there was so much experimentation, however, and gives you a real idea as to the white heat of technology that Swindon represented in the early 20th century.

The final County design was the one that was designed by Frederick Hawksworth towards the end of the Second World War and we shall have a chat about that next time.

*The sole survivor of the class being our very own No. 6106.

FRIDAY 11 AUGUST

The County Set - Part 1: Churchward’s First Version

There have been two classes of Great Western Railway locomotives that were named after counties of the British Isles, with a third sort of adjacent class that is related. All of these designs are extinct as historic locomotives but two of the three are being resurrected through new-build projects. I thought it was about time that we had a look at the real ones to see what all the fuss was about. The first of these classes was the County class 4-4-0s. These engines are best thought of as a shortened version of the 29XX or Saint class 4-6-0s.

No 3473 County of Middlesex when new in April 1904. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

The 4-4-0 design was a popular one for express passenger engines in the UK as a whole. It had been for a long time, but the beginning of the 20th century had become the beginning of the end for this design. Train loads were getting heavier, and as a result more and more power was needed. GWR-designed 4-4-0s tended to be outside framed at this time – in that the wheel bearings sat on the outside of the wheels with the cranks for the coupling rods outside of that. The cylinders were mounted between the frames with the valve gear and so on in there too.

No 3717 City of Truro as first preserved at York Museum from 1931 to 1957. This shows how the outside frame and inside cylinder design compares with the 4-4-0 Counties. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

What Churchward decided to do was to modernise this design classic using his (then) high technology design standardisation approach. To give you an idea of how fast technology was moving, No 3440 City of Truro – a member of the 37XX or City class of 4-4-0s was built in 1903. This looks positively antique alongside the sleek, new 38XX or County class which was first built in 1904 .… The 4-4–0 Counties and the Cities have much in common. They both share the express passenger wheel diameter of 6’ 8½” and bogie wheels that were 3’ 2” in diameter. They both had 18” diameter cylinders, Stephenson valve gear and the same GWR standard 4 boiler.

No 3814 County of Chester at Paddington station. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

They were worlds apart, however, and the first thing to notice is the fact that the 38XX class Counties have inside frames. This makes a huge difference visually. The County is also styled after Churchward’s new design aesthetic. It has smooth, straight lines with a short cab and, like our own No 2999 Lady of Legend, the square dropped frames at the front and the running plate that runs rearward all the way to the end of the cab. The biggest mechanical differences are in the cylinders and valve gear.

The cylinders on the new engine are on the outside. They had a longer stroke too, increasing from 26” on the City to 30” on the County. This makes a big difference to the tractive effort. The Cities were capable of delivering a tractive effort of 17,800lbf. The Counties delivered 20,530lbf – quite the jump. In theory a great thing as trains were getting bigger and heavier, making the work more and more difficult for the Cities. Surely Churchward and his team have cracked this? A locomotive developed from well-engineered parts available through his standardisation plan. Components that were interchangeable with other classes. A compact and powerful machine for the future?

A 4-4-0 County descending the bank towards Totnes. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

Well, sadly, not so much. There were problems .… The 4-4-0 design has limited coupled wheelbase*. The coupled wheelbase on a 38XX County was just 8’ 6”. When you add to this a pair of cylinders on the outside over the front bogie which are both large and have a long stroke, things are going to start to swing about a bit when you apply power and at speed. The other issue is that having the same running gear as the Saint class, the forces you have to dissipate by putting balance weights on the wheels and so on are the same but this is on a smaller engine. Once running at express train speeds, the effect of all this mass swinging about means that the forces experienced in the track (called hammer blow) rose substantially.

When measured at 6 revolutions per second, the Cities had a hammer blow of 3.6 tons, the Saint had 6.4 tons and the County had a whopping 8 tons of hammer blow! This was for a smaller and less powerful engine than the Saint that had a higher axle weight (18.15 tons opposed to the Saint’s 18 tons). Thus it had no advantage of a wider route availability. All of these issues were compounded by the fact that the ride it gave the crew was really bad. It led to the locos being nicknamed ‘Churchward’s Rough Riders’ by the drivers and firemen.

No 3804 County Dublin at Goring troughs, hauling the 12 noon Paddington to Cardiff on 14 March 1915. Photograph in the LCGB Ken Nunn collection

All the ingredients were right. The latest Swindon boiler technology, which was an outstanding steam producer when fitted with a superheater and top feed injectors**. A powerful yet efficient drive train. But the ride and its other limitations, however, were just inescapable. It is one of very few engines that came out of the standardisation era that really didn’t work as well as it should have on paper. The first one, No 3473 County of Middlesex was completed in 1904 and was the first of an initial batch of ten. The second batch of twenty was built in 1906 and the last batch of ten, that were built with the more usual curved sections at the front and rear of the running plate, were built between 1911 and 1912.

No 3813 County of Carmarthen at Swindon on 6 February 1921. Photograph in the LCGB Ken Nunn collection

There were various chimneys used throughout the production run – some copper-capped and some not. There was an also an experiment with No 3805 County Kerry***, using a smaller Standard 2 type boiler. This was discontinued after a seven month trial in May 1907. The observant among you will have noticed that the first batch were not numbered in the 38XX series and this was remedied in 1912 when a whole host of loco renumbering was done to gather classes together and to fill holes left by scrapped engines. The Counties eventually being Nos 3800 to 3839. Given their issues, some of the engines managed to clock up reasonable service lives. However their demise, when it came, was swift. The first to go was No 3833 County of Dorset in February 1930 and the last, No 3834 County of Somerset, had shuffled off its mortal coil by November 1933. The last City went in 1931 .…

No 3823 County of Carnarvon at Reading hauling the 12.30 pm Paddington to Weymouth on 13 March 1926. Photograph in the LCGB Ken Nunn collection

And there the story should have ended but for an idea that involved the use of the parts of the last locomotives that remained in Barry Scrapyard. The original vision was to create replicas of all three of the GWR County classes. Only two of these projects have been enacted upon. We have discussed the County of Glamorgan project before in Going Loco but the 41st Churchward County – No 3841 County of Montgomery is well underway. Despite having its concept in the GWS, this became an independent project that is assisted by the Great Western Society. To find out more about the interesting mission of the Churchward County Trust to bring back a ‘rough rider’, more details can be found on the 'Churchward County' website.

No 3816 County of Leicester was one of the members of the class given the 8-wheel tender from The Great Bear in the hope its longer wheelbase would steady the rough riding of the locomotive. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

Although the design waned in popularity as the 20th century went on, high power 4-4-0s didn’t end here either. The London and North Eastern Railway built the D49 class between 1927 and 1935 which had a tractive effort of 21,556lbf. The most powerful of them all was the Southern Railway V or Schools class, which had a tractive effort of 25,130lbf. The secret to this success? Both these types had three cylinders, thus better balancing the forces by spreading them about.**** Next time, we delve into the other rough rider, the 4-4-2 County tank. See you there!

No 3828 County of Hereford at Old Oak Common on 11 October 1930. Photograph in the LCGB Ken Nunn collection

* The distance between the first and last coupled driving wheels – the ones with the rods on.

** The position where the water being fed into the boiler come in. You can feed it into the bottom of the boiler, into the back head (the rear panel of the firebox in the cab) like in No 2409 King George, or in the top as part of the safety valve casting. Top feed is how it is done on the vast majority of preserved GWR steam engines.

*** These engines were built before Irish independence in 1922. Therefore there were a number of locos that were named after what we know as Irish counties today. These are:

No 3801 County of Carlow

No 3802 County Clare

No 3803 County Cork

No 3804 County Dublin

No 3805 County Kerry

No 3806 County Kildare

No 3807 County Kilkenny

No 3808 County Limerick

No 3809 County Wexford

No 3810 County Wicklow

**** Which led me to suppose – what if Churchward had used the 4 cylinder design of his Star class engines rather than the Saints? There are several reasons you would not want to do this but still, it’s always fun to think about the roads not travelled.

The most powerful 4-4-0 in Britain, the Southern Railway Schools class. No 30927 was built in 1934 as SR No 927, and named Clifton after Clifton College in Bristol. This photograph was taken at Basingstoke on 1 July 1961 as the locomotive was about to haul a stopping train to Waterloo. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

FRIDAY 4 AUGUST

Guided by a North Star

The name North Star was applied four times to locomotives in the history of the Great Western Railway The second time was the Sir Daniel class 2-2-2 No 380, built in 1866; the third was the Dean Single 4-2-2 No 3072 built in 1898, although this one lost her name in 1906 when the title was about to be conferred on No 40 – the prototype of the GWR’s magnificent four-cylinder express passenger locomotives of the 20th century.

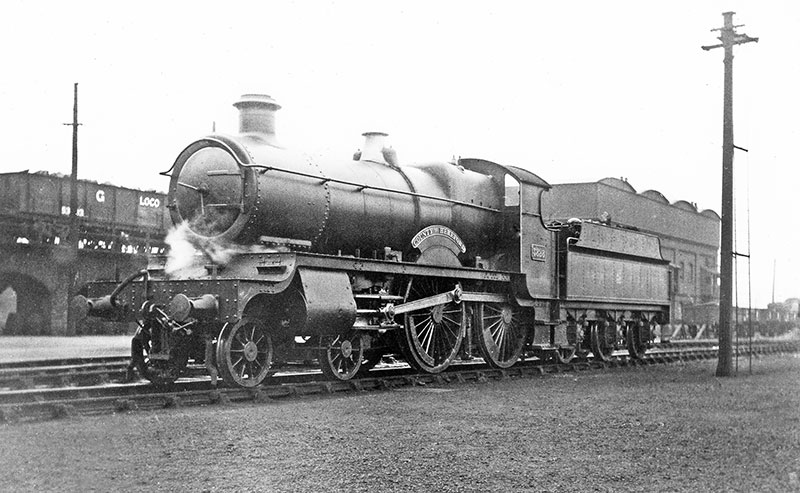

No 40 North Star was later renumbered 4000 as the first of the Star class, and in 1929 was rebuilt into a Castle class locomotive, as shown in this photograph from the 1930s

The first North Star, however, is at least as important as her successors, if not arguably more so (and that’s coming from a Castle obsessive!). The very earliest days of the GWR were mired in locomotives that were at best mediocre and at worst barely capable of moving themselves, let alone their train.

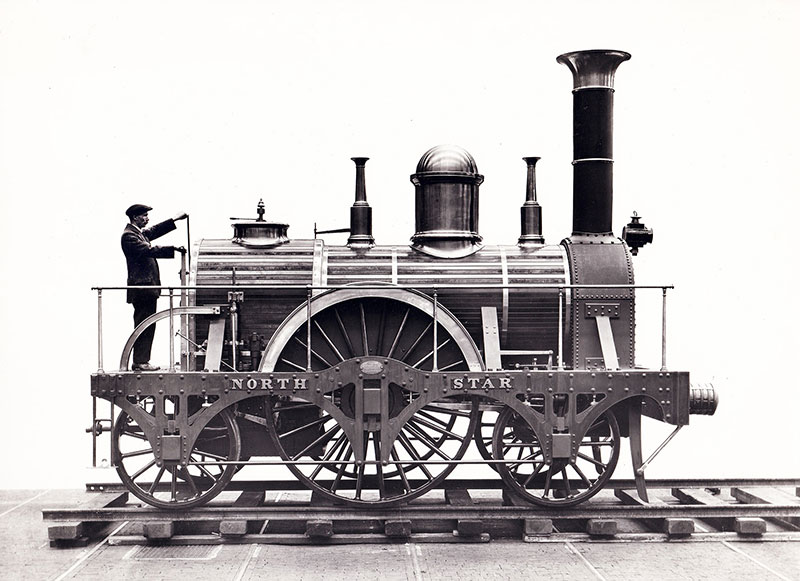

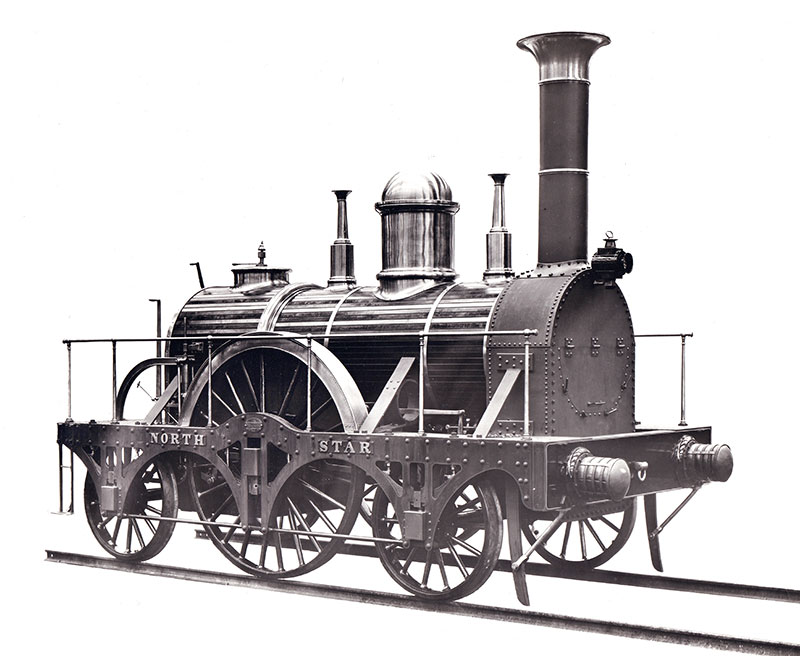

The 1925 replica of North Star shows her in the original 1837 condition

Into this less than desirable situation walked Daniel Gooch. He was the first locomotive engineer of the Great Western and he was given a very difficult task. The engines that were available to him frankly sucked more than a room full of vacuum cleaners and this was down to a number of factors. One of which was that at this stage (the late 1830s), the technology was still in its infancy. We talk of the 1950s and 1960s as being the very exemplar of the ‘white heat’ of technology but it is arguable that the railway revolution was as radical a shift, if not more so.

But this comes at a price. Not all of the developments will be good ideas. Those that are not will become evolutionary dead ends. Without the benefit of hindsight, how do you tell?

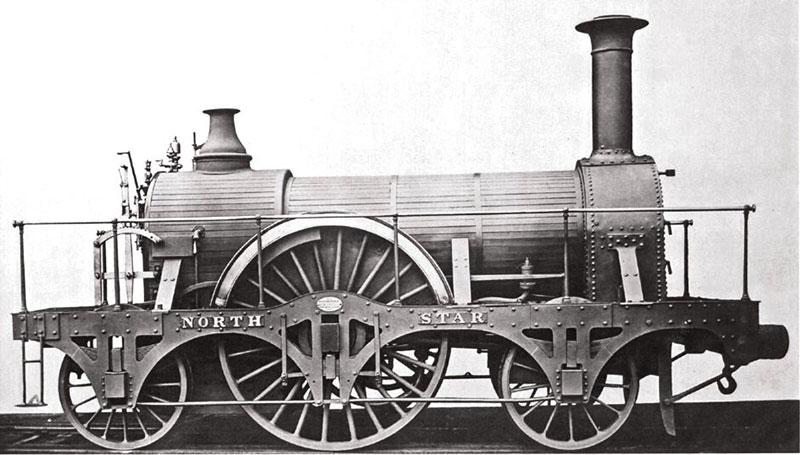

The original North Star as she appeared later in her career with longer frames

Another is that the great engineer who designed the line, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, had initially not really got a great handle on the design requirements of railway steam locomotives. His requirements were very exacting and really tied the hands of the locomotive engineers. It’s weird to think that this great genius had a blind spot, but he did! To be fair to him though, this was a new technology and I refer you to my previous point.

The board of the GWR were obviously concerned and they headhunted Gooch to fix their problem. I’ve talked about him before, but he was basically helicoptered in to sort the mess. He previously worked for Robert Stephenson & Co, designing and building some of the most modern locomotives of the era. This is where the fates stepped in.

Having just left Stephenson’s, he was aware of the fact that a pair of 2-2-2 locomotives had been built for the New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad in the USA. For ‘financial reasons’, the company never shipped them to America and they were sitting in the locomotive works in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. They had been built to that railway’s track gauge of the 5’ 6” (1,676mm) and therefore required modification to fit on the 7’ 0¼” (2,140mm) track of Brunel’s railway, but otherwise they were a shortcut to getting the show on the [iron] road.

The first of these locomotives was shipped to Maidenhead in 1837 by barge and there her wheels first hit the rails on which she was to become famous. There were just ten engines available for use by the time the inaugural train was to be run between Paddington and Maidenhead in May of 1838*. The only one that Gooch felt that he could rely on to do the job was this engine. She had been named North Star (broad gauge locomotives of this era never had numbers) and it performed the prestigious duty admirably.

There was one issue however with North Star and her compatriot** – they had a tendency to be consume coke*** at what was perceived to be too high a rate. Both Brunel and Gooch looked into this and redesigned the way that the exhaust steam was ejected via the chimney and pulled fresh air into the fire. This worked very well and started the tradition of expertise in what became known as draughting at Swindon Locomotive Works. North Star was further updated in 1854. This rebuild saw the stroke of her 16” cylinders increased from 16” to 18”. She also gained another foot in the length of her frames.

She worked until 1871 and along with the other famous locomotive of the broad gauge era, Iron Duke Class 4-2-2 Lord of the Isles built in 1851, she was put into store at Swindon Works for preservation. This effort was sadly for nought as the increasing pressures for space in the works finally overcame the historical imperative. Documentation exists that suggest that the directors of the GWR tried to find a home for either or both of them for over two years. Sadly, even the organisation that is now the Science Museum said ‘no thanks’ and they were both cut up in 1906.

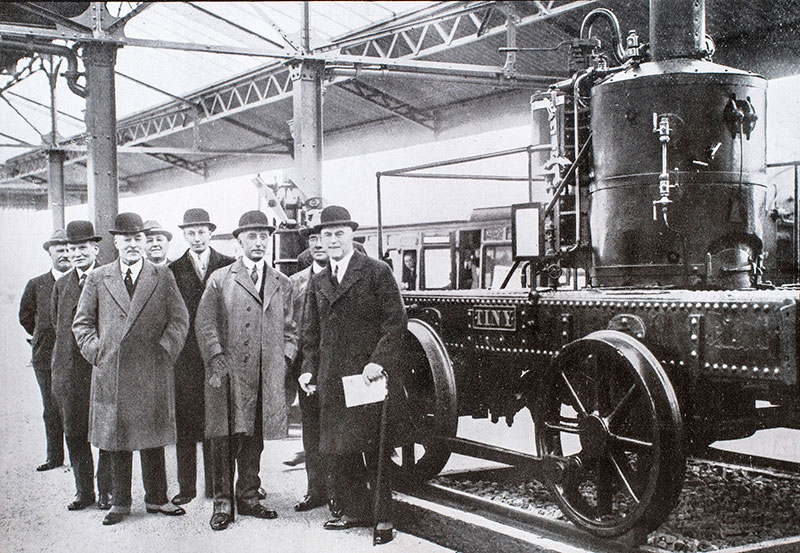

Tiny at the rebuilt Newton Abbot station in 1927, with a group of GWR directors

This act means that the only surviving genuine broad gauge locomotive is a small, vertical boiler 0-4-0 shunting engine called Tiny that lives in the museum on the South Devon Railway. This was nicely described as ‘Scrapping all the cars and other road vehicles that have ever existed except for a three-wheeled Reliant Robin and using that as the only example to remember it all by’. Not fair to Tiny – she’s a lovely little engine(!) – but in some ways, it’s accurate.

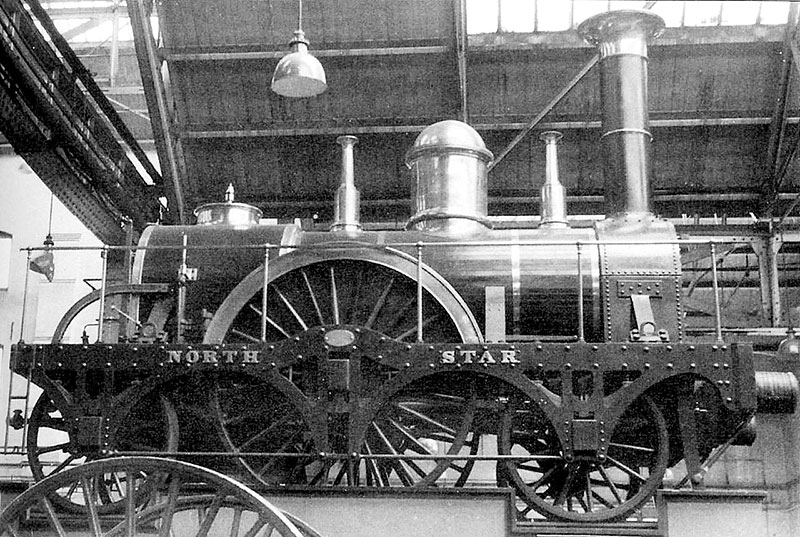

Another view of the 1925-built replica of North Star

The great irony is that nearly twenty years after 1906, the centenary of the railways was to be celebrated and the GWR now had nothing of their early era to display. To try to rectify the mistake, the directors of the GWR decided to build a replica of North Star to go to the event. The good folks at Swindon Works had a surprise for the directors however. Some parts of the original locomotive had been squirrelled away in corners of the vast site and all but one of them were gathered together to go towards the building of the new North Star. Although not operational, she represents a condition that is very close to that in which the engine was delivered in 1837.

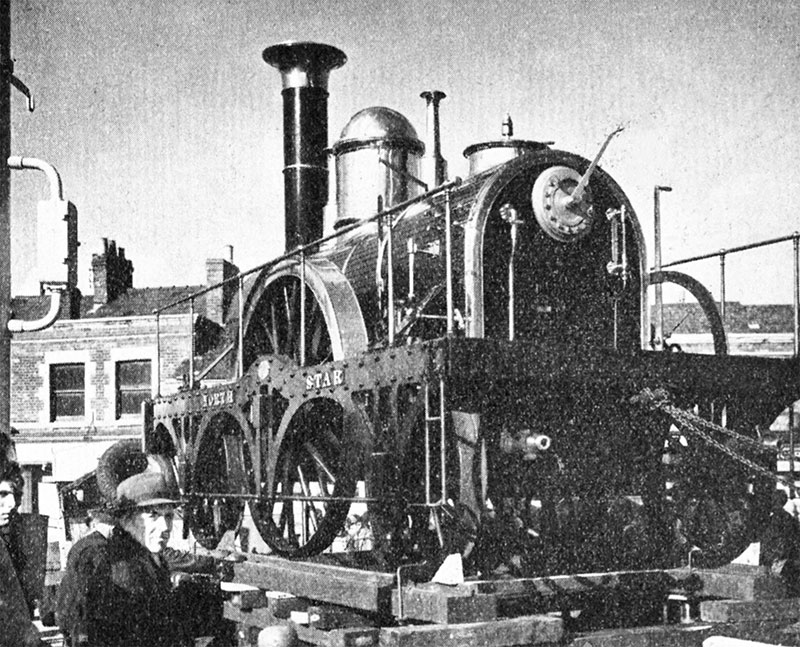

In 1935 the North Star replica re-created the opening of the GWR for the company’s centenary film. The carriages were created for the centenary of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1930

This replica visited the centenary celebrations of what was the Stockton & Darlington Railway in 1925 and two years later she went to North America with King Class locomotive No 6000 King George V to take part in the Centenary of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. She also became a part of the GWR’s own centenary celebrations in 1935. Thankfully this replica did not suffer the same fate as her predecessor and she was mounted on a raised plinth in Swindon Works****. In 1962, she took her place in the original GWR Museum at Swindon, along with the surviving driving wheels of Lord of the Isles. The collection moved to a new venue, Steam, on the site of the former locomotive works that opened in 2000.

The North Star replica on her plinth in Swindon Works

In 1950 as part of the celebrations of 50 years since Swindon became a Borough, North Star was exhibited outside the Town Hall

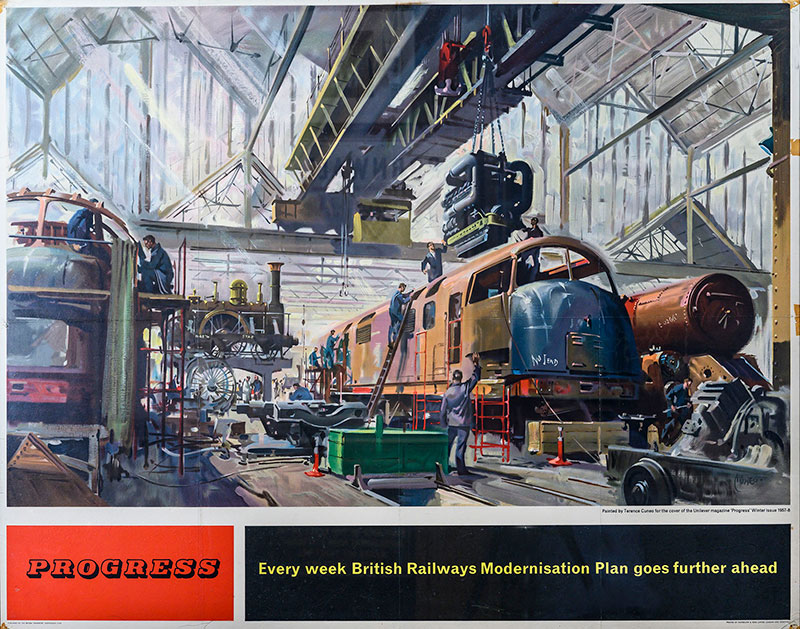

Terence Cuneo’s 1957 painting of diesel-hydraulic locomotives under construction at Swindon Works, includes North Star on her plinth in the background

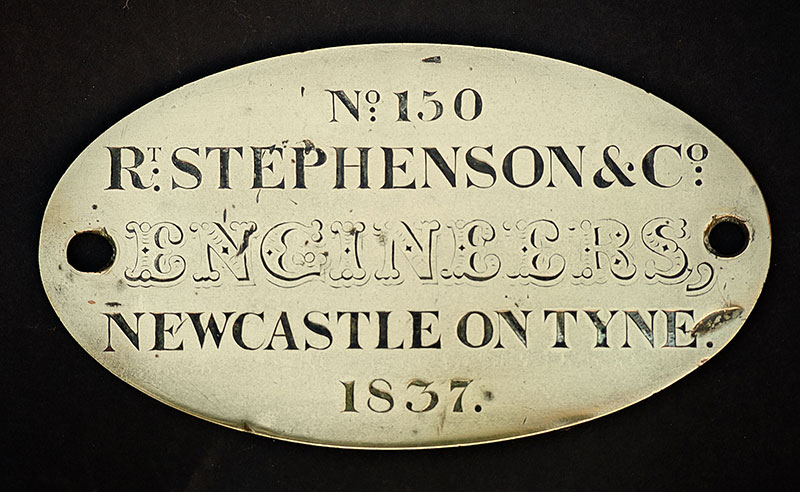

So did we all notice the little hint in there? All but ONE of the pieces were incorporated into the replica? Well, there is a part of this historic machine that is not at Swindon. It’s with us at Didcot. A trip into the museum will reveal that one small but very important part of North Star is inside. The brass plate records that the engine was works No 150 for Rt. Stephenson & Co., Engineers, Newcastle on Tyne, 1837. It is amazing to think that both Brunel and Gooch would have both seen and possibly touched this thing and its historical significance is amazing to contemplate. It might be part of the Great Western Trust’s collection but it has enormous meaning for their friends in the locomotive department. This is the literal Genesis for all the engineering excellence that we have the great pleasure of taking care of today.

The original North Star works plate in the museum at Didcot Railway Centre

*The magnificent elliptical arch bridge at Maidenhead wasn’t opened until 1839, so there was a bit of a restriction in going all the way to Bristol!

** She arrived in 1839 was named Morning Star.

*** The early locomotives burned coke – coal that has been heated in an airless environment to drive off impurities. Amazingly, the people of the early 19th century had passed environmental-protection legislation to make sure that these new-fangled steam engines didn’t fill the atmosphere with thick smoke. Nothing is truly new!

**** Which make you wonder why they didn’t just do this to the original in the first place but there’s nowt so uncommon as common sense .…

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.