Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - November 2023 - Going Loco - November 2023

Going Loco - November 2023

FRIDAY 24 NOVEMBER

Going Loco Personality Profiles – the Armstrong Brothers

The names of the Armstrong Brothers – George and Joseph – are sadly lesser-known today than other Great Western Railway engineers. No locomotives are preserved from either brother and they tend to blend into the background when compared to their predecessor, Sir Daniel Gooch or their successor, William Dean. This is a real shame as they had a massive influence on the GWR and helped it through some particularly tough times. Let’s see if this little corner of the internet that is forever painted middle chrome green with a copper-capped chimney can help rectify this.

This portrait of Joseph Armstrong was published in the Great Western Railway Magazine in July 1891

The Armstrongs were born into that era when the steam locomotive and the railways they ran on were still a huge leap in technology. They weren’t at the tip of the spear so to speak, but they were around to see it as youngsters. Joseph was the older, being born in 1816 in Bewcastle, Cumberland on 21 September. His family spent some time in Canada and it is here that modern historians believe that George was born. The discrepancy being on his gravestone which states his place of birth was the same as his brother who was born on 5 April 1822, and as his family was in Canada from 1817 until 1824, this seems like a mix up with his brother.

This portrait of George Armstrong was published in the Great Western Railway Magazine in March 1895

Upon their return to the UK, their father became a bailiff for the Duke of Northumberland. This put the brothers in Newburn-upon-Tyne – a prime place to see steam traction on the railways. Their school was the same one Robert Stephenson had attended. They were also at one end of the Wylam Waggonway where the pioneering preserved locomotives Puffing Billy and Wylam Dilly were working. Not far from the Stephenson loco works either. 1836 found Joseph working as a loco driver on the Liverpool & Manchester Railway and then on the Hull and Selby Railway. His brother followed in his footsteps with the exception of a short period in France which he found a little bit too unstable politically .…

During the 1870s and 1880s renewals were built at Swindon of the original ‘Iron Duke’ class broad gauge locomotives. This photograph, by Rev A H Malan, shows Timour, built in July 1873, hauling an express at Teignmouth on 7 May 1891

Through a few career manoeuvres, they ended up working for the Shrewsbury & Chester Railway. This railway pooled its engines with the Shrewsbury and Birmingham Railway and the Armstrongs became Locomotive Attendant (Joseph) and Assistant Locomotive Attendant / Works Manager (George). These two railways were amalgamated into the Great Western in September 1854 and as such their locomotives were the first standard gauge engines owned by the then exclusively broad gauge GWR. The GWR wanted to use the Wolverhampton works as a plant to build the new standard gauge engines they were going to need. The government had forbade any further expansion of the broad gauge, except in the west of England, so it was only going to contract from here on in. The first engines were built in the shiny new factory in 1859.

No 727 was one of the ‘Buffalo’ class of 266 large 0-6-0 tank engines built at Swindon between 1870 and 1881. No 727 was built in October 1872

While there had been a degree of autonomy for Wolverhampton, the full ‘take over’ of the Armstrong brothers occurred with the resignation of the GWR’s first locomotive engineer, Daniel Gooch, in 1864. This was when Joseph Armstrong took up Daniel’s post at Swindon. George in turn then took up Joseph’s post at Wolverhampton.

Joseph was a highly popular manager and was very well regarded both in the Works and the wider town of Swindon. He had quite the job. The maintenance and partial replacement of the broad gauge fleet as well as managing the continued march of the standard gauge railway was complex. The areas where they rubbed shoulders – the mixed gauge – was even more complex. The GWR was entering a time of massive growth and this was a huge task. One that would take its toll on Joseph.

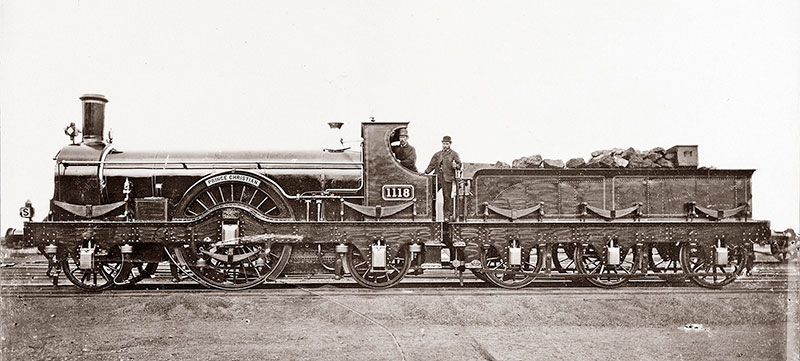

No 1118 Prince Christian of the ‘Queen’ class was built at Swindon in March 1875

George hadn’t been made the GWR’s assistant locomotive engineer – it was a difficult situation for Joseph. They had been together in their careers for a long time but it would look very much like nepotism if George got the job. The solution was to essentially give George free rein to a reasonable extent at Wolverhampton and to give the assistant job at Swindon to a young blood by the name of William Dean. You might have heard of him .…

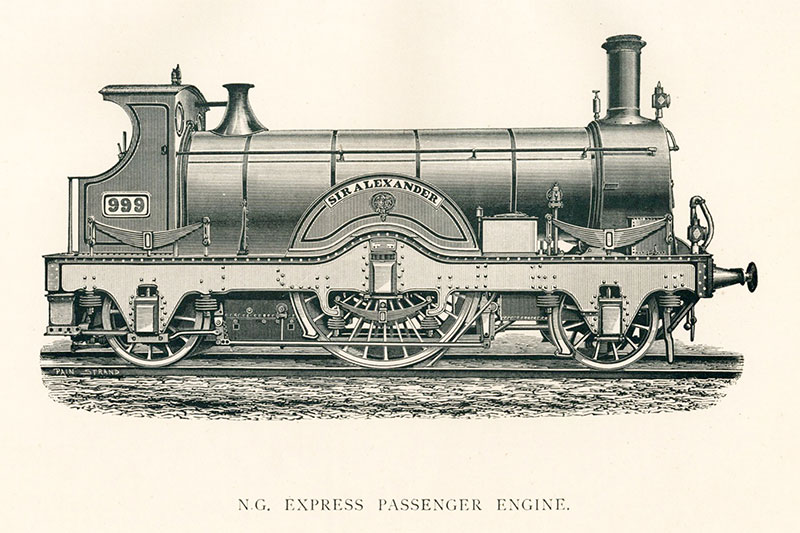

No 999 Sir Alexander of the ‘Queen’ class was built at Swindon in March 1875. This drawing was published in the Great Western Railway Magazine in March 1891

As well as the huge tasks that the GWR demanded of him, Joseph was also a lay preacher in the Methodist faith and yet ensured that all the denominations of Christianity had a place of worship in Swindon. He was the chairman of the Swindon New Town Board. He was involved in getting the town waterworks set up so that everyone could get access to fresh water. He took part in the running of the medical fund, the cottage hospital and the range of other mutual benefit societies.

No 155 of the ‘Chancellor’ class was originally built in September 1862 by George England & Co. She was renewed at Wolverhampton in January 1883. This photograph was taken by R Brookman after she was reboilered in November 1910

By 1877 his health was poor. Joseph was a typical Victorian workaholic and he began to show the signs of trouble with his heart. Typically of the man, he refused until nearly the end to take a holiday for the benefit of his own health. He was on his way to Scotland but never made it. He got as far as Bath when he suffered a massive heart attack and passed away. So regarded in Swindon was he that his funeral was attended by 2,000 workers from Swindon Works as well as 100 from Wolverhampton and several other deputations from all over the GWR network. Dean was Joseph’s successor at Swindon but he also realised the benefit of leaving his brother where he was to get on, and George carried on for another twenty years. George finally retired in 1897 and passed away in 1901 after a fall at a floral fete.

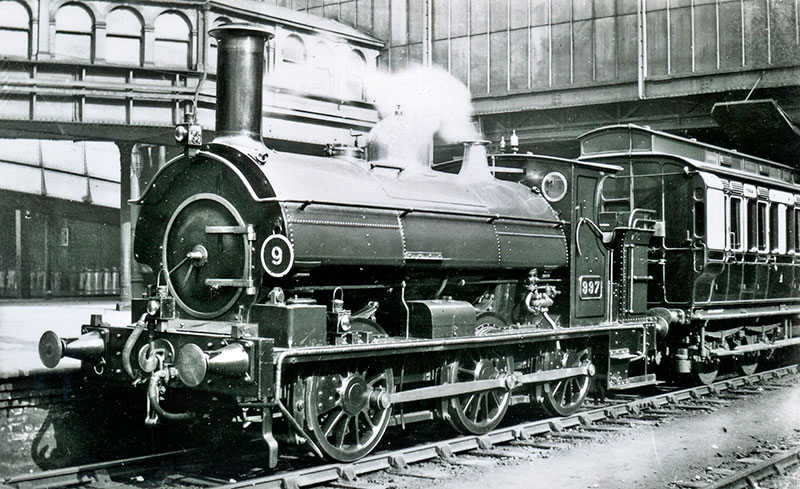

No 997, a member of a numerous class of small 0-6-0 tank engines built at Wolverhampton between 1874 and 1895. They worked all over the GWR system and No 997 is here on station pilot duty at Paddington

The locomotives they both produced were many and various and really deserve us having a chat about them at some later date. The sad thing is that there are no survivors. For all they did and all they meant to the towns of Wolverhampton and Swindon, there is no locomotive reminder for us to marvel at. This is a real shame as it means they tend to get overlooked. They were a huge and very important stepping stone from the Brunel and Gooch era to that of Dean and Churchward and the dominance they represented. Without them, that later era couldn’t have been the same .…

FRIDAY 17 NOVEMBER

How The Other Half Travel – Broadly Speaking .…

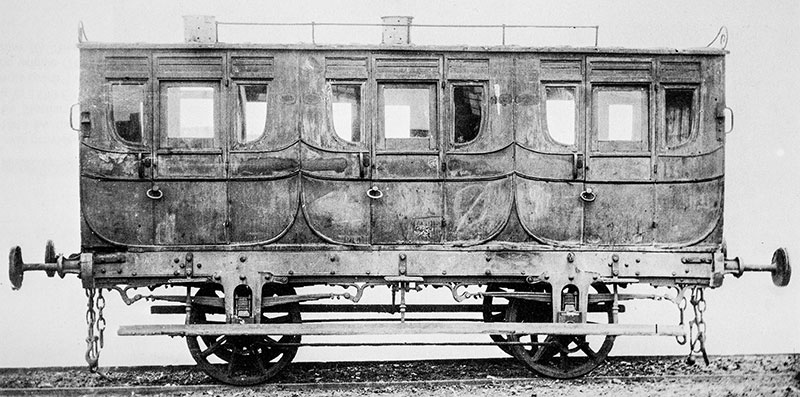

A three-compartment broad gauge first class carriage built in 1850 by Messrs Wright of Birmingham. The vehicle was panelled in papier maché. Photograph published in A Pictorial Record of Great Western Coaches by J H Russell

So I promised you a little something special last week and here it is – an exhibit that not many people that have seen but is of national importance and, like many of the hidden treasures of the Railway Centre, is just awaiting its moment to shine .…

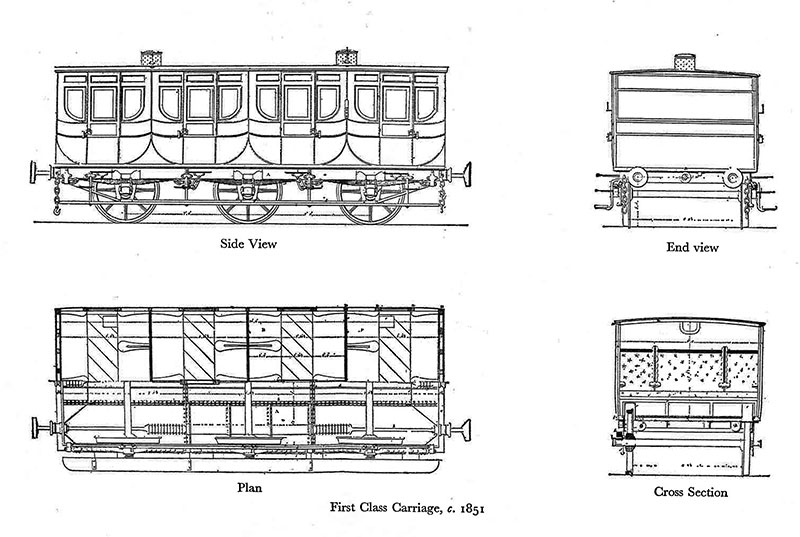

A drawing of a first class carriage, c. 1851, from E T MacDermott’s History of the Great Western Railway

First class travel was in the mindset of the builders of the Great Western Railway. Strange as it may seem today, the thought of massed transit as a concept hadn’t really been appreciated by most railway companies. In fact, they were downright hostile to the idea. There was the oft quoted phrase about the railways – that they would ‘allow the lower classes to move about’ … In the end, it was the government realised that ‘allowing the lower classes to move about’ was actually a good thing. The ability for the workforce to be able to travel longer distances, to commute as it became known, was beneficial to the national economy.

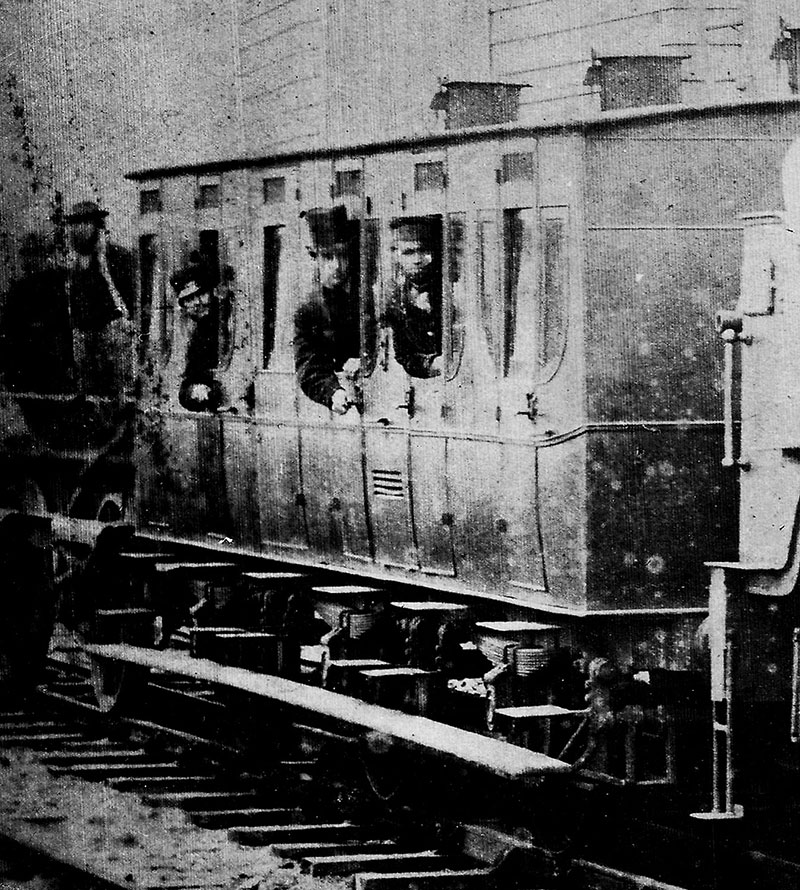

Queen Victoria’s broad gauge carriage of the 1840s has detailing derived from the stagecoach origins of railway passenger vehicles

However, that was of little concern to the very rich. As today, there were a good number of extremely wealthy people in the UK. Much as the IT revolution created millionaires and billionaires, the Industrial Revolution’s hyper rich joined the upper classes in having a wallet so thick that you could use it as a doorstop. People with that kind of money like to travel in style and the Great Western Railway was happy to oblige. The Times wrote on 13 August 1863:

“The Great Western is the Prince of Railways. It has the broadest gauge in the world and the biggest carriages in this country. There is an odour of Royalty about the whole establishment. At the station there are fine carriages, livery servants, ladies’ maids, and lapdogs. On the platform are lords, ladies, and, perhaps, the French Ambassador or the Italian Envoy. Your fellow passengers are officers of the Household Troops going to Windsor, or lads to Eton, very full of yesterday’s match at Lord’s. As you are whirled along in easy and rapid motion through some of the most spacious plains in England, by palace, school and college, with the Thames showing his face now and again, you feel you are in good company, and that it is well to be there.”

The first broad gauge train at Redruth in 1867. The West Cornwall Railway from Truro to Penzance was built to standard gauge and a third rail added to allow broad gauge trains to run through from London to Penzance in 1867. This is evidently a standard gauge body converted to run on the broad gauge, with wide footsteps. It has the stagecoach-style windows with curved shape at the bottom

The trains through to Bristol were connected to ships to New York. A truly staggering notion in the mid nineteenth century but it was one that was aimed squarely at the first class patrons.

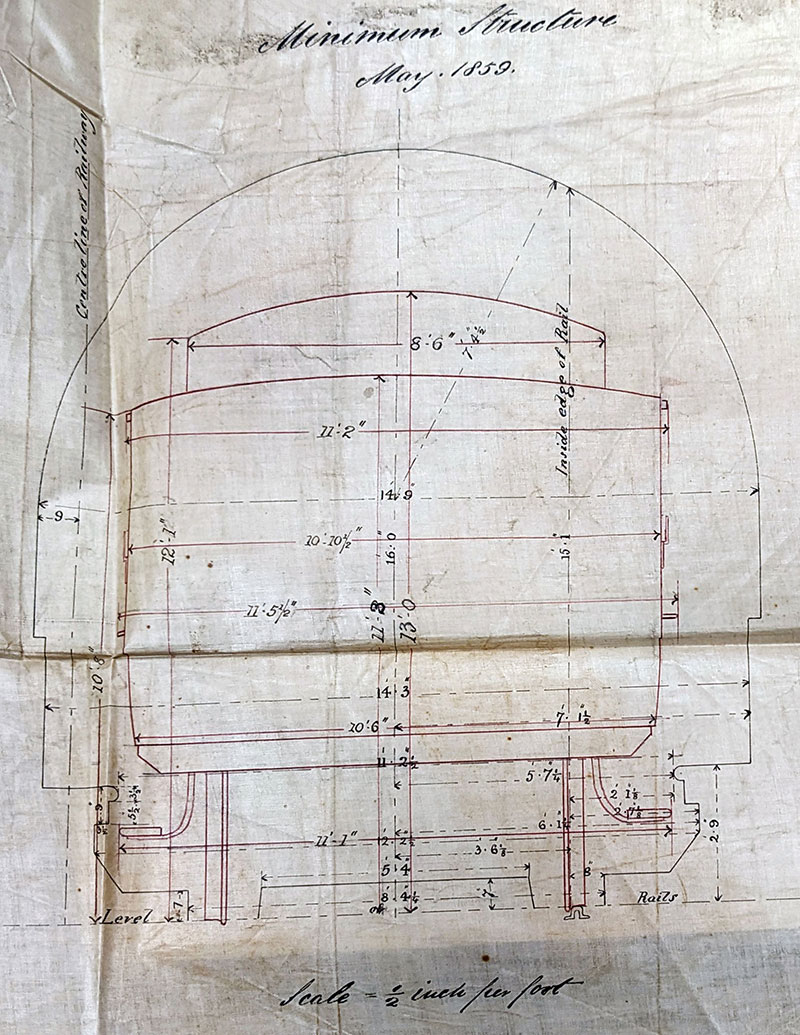

A broad gauge loading gauge diagram of 1859. You will note that carriages could be more than 11 feet wide – that is two feet wider than current trains on Britain’s railway network! The diagram is in the Christison album in the Great Western Trust archive

The carriage body now in our collection is a four compartment first class coach. The number is not currently known but it is believed to be of a type that was constructed around 1850. The body is largely complete and was once upon a time set on a six-wheeled chassis although this is long gone. It has no corridor and no bathroom. It had seating for four people across the width of the compartments. This sounds like a lot, but when you consider the advantages of space afforded by Brunel’s 7’ 0¼” gauge track, this is actually pretty generous. The seats were quite like the deep wingback chairs of the Victorian era and were lavishly upholstered. Sadly, none of that finery still exists in this body.

A broad gauge carriage in the sidings of condemned vehicles at Swindon after final abolition of the broad gauge in 1892. This is an early vehicle and has stagecoach-style windows with curved shape at the bottom. It also has a rack to allow luggage to be placed on the roof

This coach was actually built by outside contractors. The GWR didn’t start building its own coaches until the 1860s. There was some discussion as to where the GWR would put its carriage works as it had to be accessible by both the broad gauge and standard gauge and this at the time ruled out Swindon. That site was broad gauge only. Many other sites were considered one of which was Abingdon / Radley area. However, by the time it was all settled, the mixed gauge had reached Swindon and the carriage works were sited there anyway.

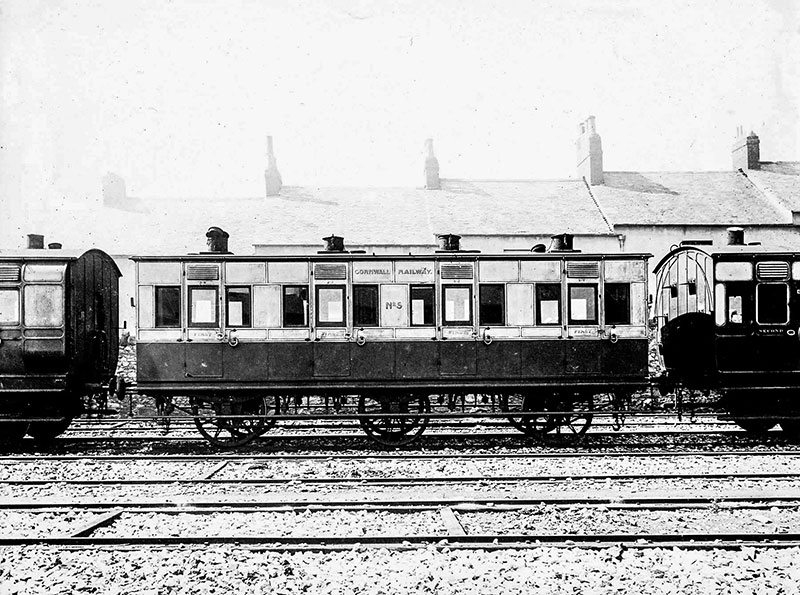

A later design of Cornwall Railway first class carriage with very square shaped windows and detailing. Photograph in Peter Lugg’s collection in the Great Western Trust archive

The carriage’s discovery was made more than twenty years ago and it wasn’t the Great Western Society that found it – it was members of certain group called the Firefly Trust. That’s them – those fine people that built the engine that stands at Didcot today! Despite its privileged beginning, the body was sold off at the end of the broad gauge and was eventually found being used on a Shropshire farm. From transporting the great and good (or at least the rich!), it had the far more humble role of being a home for the farm’s chickens!

Part of the broad gauge first class carriage now at Didcot, being loaded during its original recovery

It was one of those most fortuitous discoveries as the landowner was looking to get rid of the coach body and was about to demolish it. Being well aware of the national significance of their find, rather than lose this precious artefact totally, its saviours organised for the body to be cut into four manageable sections. While this seems to be counter-intuitive, it was that or lose it altogether. The cuts were made in the middle of each of the four compartments – the area where the least material had to be damaged.

The first class carriage on arrival at Didcot, showing detailing which is a throwback to stagecoach design

While there was none of the running gear remaining, there was one of the original 25ft long wooden solebars – the chassis side beam – still extant. This was also saved. The sections, along with the doors and the ironwork that had survived was then loaded onto a lorry and driven off to safety. Safety being a Firefly Trust member’s garage in Newick, East Sussex. And that’s where it stayed. For over twenty years. Unseen by most but safe and dry. Time rolled on .…

Part of the roof of the first class carriage, with Peter Jones looking through the hole where an oil lamp would have been positioned at dusk to allow a modicum of illumination in the compartment

Years after the completion of their locomotive, Fire Fly was eventually donated to the Great Western Society and became part of the permanent collection at Didcot. The Firefly Trust thought it was appropriate for the coach to also become part of the collection at Didcot. Needless to say, the opportunity to add what is probably the only complete original 7’ 0¼” gauge coach body left in the world to the collection was jumped at. This means that the collection does truly extend from those early broad gauge days to the British rail era. The coach body was quietly delivered to site and it currently resides in storage.

A door of the first class carriage, complete with door handle

The future of this coach body sadly does not include an operational role. The sheer rarity of it and the condition of the timbers mean that it would be impossible to rebuild the coach without massive loss of what is now unique historical fabric. As much as we love having operational vehicles at Didcot, it just wouldn’t be right to do in this particular case. The plan long term is to take the body and reassemble it so that it can be cosmetically and sympathetically restored and then displayed. It can then be appreciated as the unique and hugely important artefact that it is.

Another part of the first class carriage being unloaded at Didcot. These portions are invaluable evidence of how the vehicles were constructed. Note, the electric light switch on extreme right is not part of the original equipment!

FRIDAY 10 NOVEMBER

Passengers – Broadly Speaking…

Having had a chat last week about the engines that pulled such legendary trains as the Flying Dutchman, it makes all sorts of sense to have a look at the coaches that went with them – at least in the early days. Which is handy really, because we have a couple of items for our visitors to look at in this regard .…

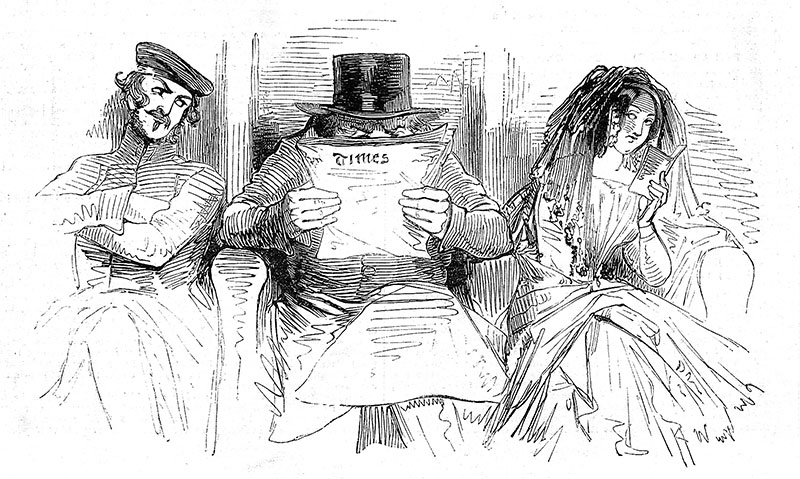

First class passengers studiously avoiding the temptation to speak to each other, from a sketch published in the Illustrated London News in the early 1840s

Passenger coaches of this age were very primitive in many respects. Firstly, they were rigid framed. More modern coaches have four or six wheel bogies or trucks at each end. The early coaches – like the early locomotives – had all their wheels mounted rigidly in the frame. They tended to be of a six wheel configuration but coaches with four or even eight wheels were seen on the broad gauge. They were also far more akin to their horse-drawn ancestors in their construction.

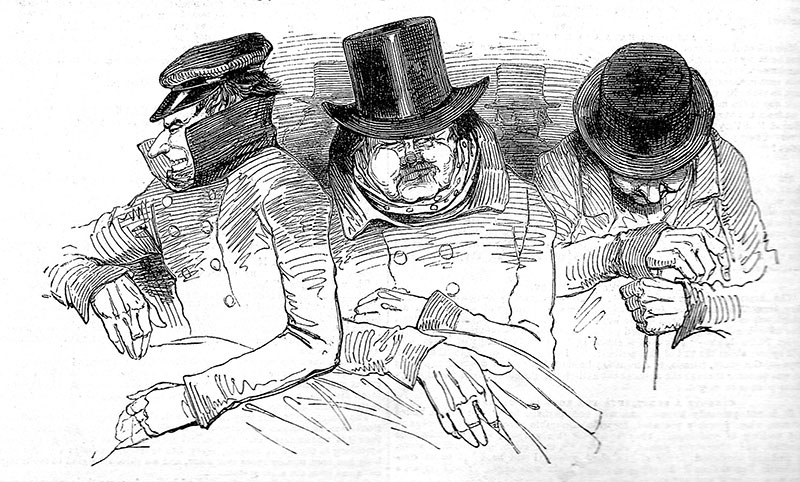

Second class passengers doing their best to stay warm, from a sketch published in the Illustrated London News in the early 1840s

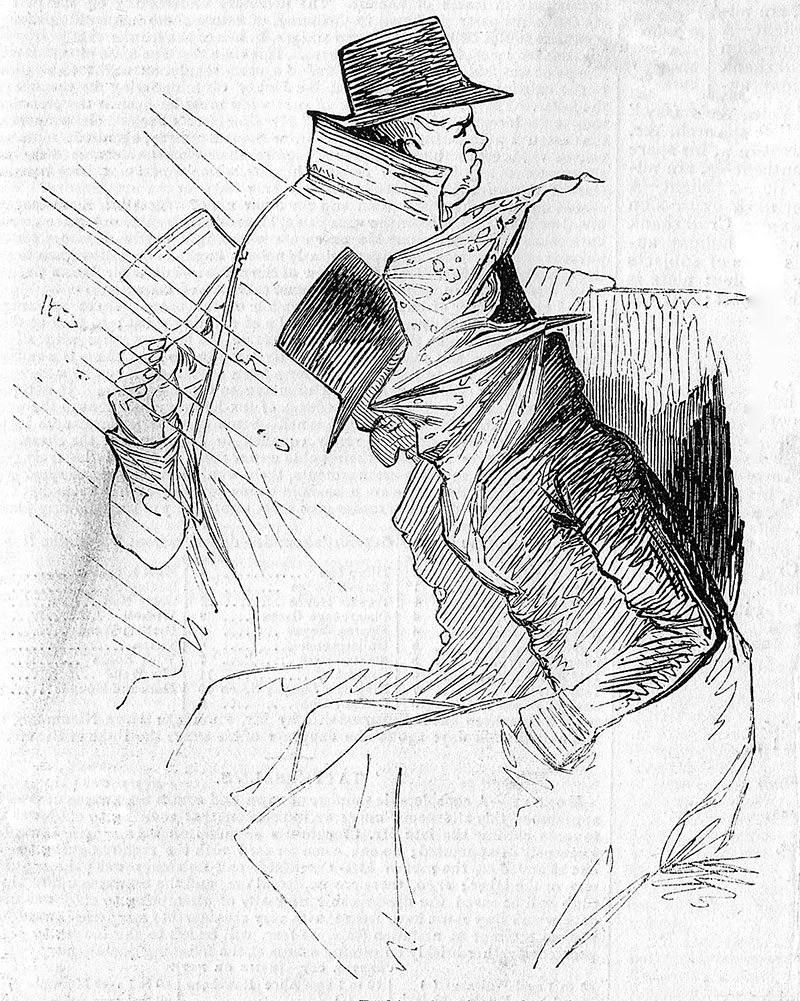

Third class passengers in a rainstorm, from a sketch published in the Illustrated London News in the early 1840s

Continuous brakes* were something that would only happen in the future. The earliest locomotives were not well equipped in the brake department. The provision of a handbrake with wooden shoes on one side of the tender was a good level of equipment .… The guard would have a handbrake at his end too. The provision of such simple things as windows, side walls or even a roof wasn’t guaranteed either.

When the replica second class coach arrived at Didcot to run on the broad gauge the body, built of softwood in 1985, was in poor condition so it was completely rebuilt by Pete Silver in hardwood

First class coaches were always well appointed – as you might expect. The early ones were very much based on stagecoach practice. It was a known technology and therefore a transferable set of skills. They looked quite a lot like a bunch of stagecoaches, placed together in a railway chassis. Probably because they were!

The second class coach being moved after rebuilding, from the Carriage Shed at Didcot to the Transfer Shed, using two standard gauge four-wheeled trolleys

Take a look however, at the two replica coaches that were built to accompany Iron Duke for the 150th anniversary of the Great Western Railway in 1985. One is second class and the other third. The second class coach at least possesses some modicum of walls and a roof. No windows, clearly, or anything to keep the rain out if it’s blowing sideways, but a roof .… The third class passenger ‘coach’ is even more spartan. I believe the recipe for making one is to take one open wagon, add bench seats. That’s it. The whole thing. No frills. Not anything at all. Can you imagine a winter journey from London to Swindon at 75mph as described last week?

When the second class coach had been completed, Helen Ashby of the National Railway Museum transferred ownership of the vehicle to the Great Western Society in recognition of the work done in rebuilding the body. She is seen here at the handing over on 2 April 2010, with Richard Croucher, on the right, receiving it. Pete Silver is on the left of the photograph

The railways were surprisingly reluctant to take passengers of all classes aboard their trains. It was only in 1844 that the government stepped in and an act of parliament was passed in order to ensure that train travel was available to all at reasonable cost. It also insisted that at least one train a day with third class accommodation should travel the entire line, stopping at all stations. These were called ‘Parliamentary Trains’. These trains should not travel at less than 12mph. and that the passengers should be protected from the weather and provided with seats. They should also allow passengers to carry 56lbs (25kg) of luggage for free as well. While this all seems very altruistic, the main aim was to mobilise the workforce to benefit labour supply.

Passengers in the third class coach, dressed in Victorian costumes, on Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s 200th birthday, 9 April 2006

The remains of Brunel’s broad gauge railway are pretty sparse – especially considering that it lasted until the 1890s. However, of those sparse remains we do have a couple. The first is a section of a coach that was built for the Bristol and Exeter Railway. This was a line engineered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel and as such was built to his broad gauge. We don’t know a huge amount about the coach. We know it had the number 250 and that it was a third class coach, but as to what type and even when it was built – a that’s more difficult to say. Thoughts over the years have ranged from a brake third** or a third class coach with a central luggage compartment.

Ragged Victorians in the third class coach

It was found by Sean Bolan, member of the Guild of Railway Artists, who discovered it in use as a forester’s refuge not far from Moreton-in-Marsh. It had been there a long time, graffiti in it hints at its use by the land girls in the Second World War. There is enough remaining of the coach to allow us to construct a compartment. Pressures of time and space have prevented this so far. It provided a great deal of information that was used when the coaches that ran with Firefly were rebuilt when they came to Didcot.

Part of the coach body discovered by Sean Bolan near Moreton-in-Marsh, now in the Carriage Shed at Didcot

We also have the remains of a first class coach. This is another extremely rare example. This is probably a story for another day – I’ve just received the background for this one, so we’ll come back to it next week .… The early broad gauge era was really the beginning of fast mass transit for everyone. Although in those early days the price, even as set by the government, was still quite high for the average worker, it did open up a whole new world of opportunities for many. Yet another thing we take for granted today that the railways provided.

One that got away – this broad gauge coach body was photographed by Phil Kelley at Midgham on 5 August 1961, but was subsequently scrapped

* The provision of a brake on each vehicle in a passenger train that can be operated from the locomotive and that put the brakes on if the vehicles of the train separate.

** A third class coach with a guard’s compartment.

FRIDAY 3 NOVEMBER

Iron Duke – The BIG Name in 19th Century Heavy Metal?

Well, no, not really .… He was quite the chap though. Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington was a statesman, a soldier and all round pinnacle of the 19th century in many ways. Interestingly, he was actually of Anglo-Irish extraction. It is unexpected by some that this British icon was born in Dublin. Prime Minister, one of the key figures in the final defeat of Napoleon and so on, and so on. If you were someone of note in the Victorian era, you had stuff named after you. The Duke was no exception. Especially when you have a really catchy nickname like ‘The Iron Duke’!

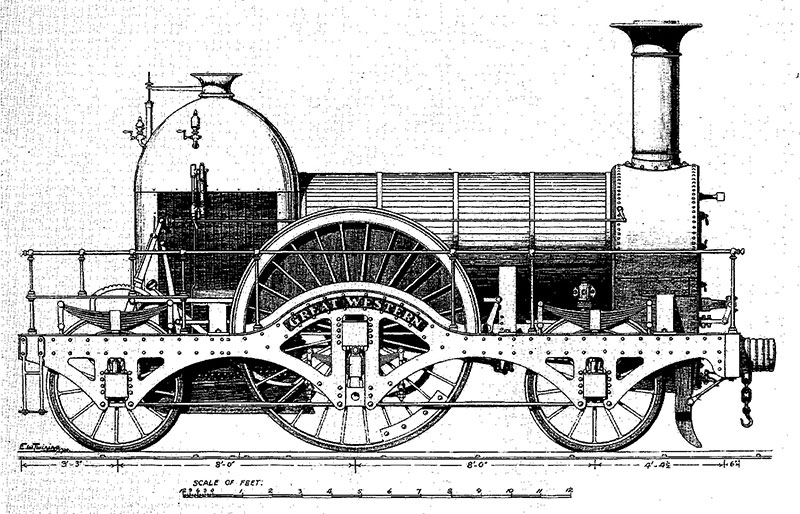

Great Western as originally built in April 1846 as a 2-2-2

It is said that far from being the kind of awesome nickname that you’d want on a T-shirt if it was given to you(!), it was used somewhat disparagingly after he added iron shutters to his London house to prevent damage by rioters.

Among the multitude of different things that were named after the man and the nickname was a class of locomotives. These were based on a single machine called Great Western designed and built at Swindon in 1846. This was a broad gauge locomotive with a cavernous 7’ 0¼” between the rails. She was built as a direct development of the Firefly class which we have looked at previously through our replica.

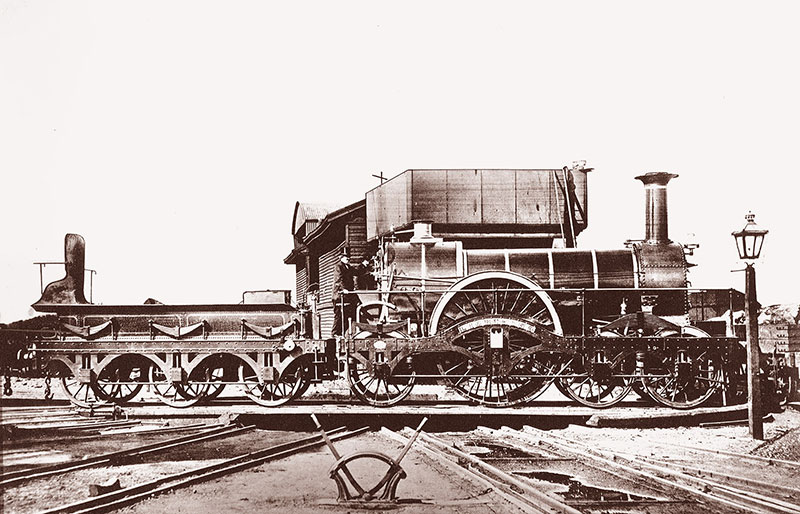

Lightning built in August 1847

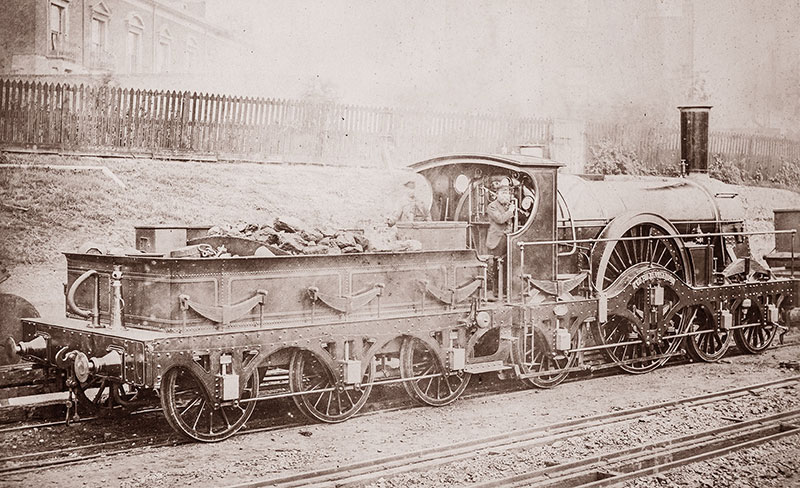

The driving wheels were a foot larger than the Fireflies making them no less than 8’ in diameter. The big takeaway from the experience was that the best thing to do with a 2-2-2 was to add a fourth axle and turn it into a 4-2-2. The reason being that Great Western suffered a broken lead axle and the weight was better spread over more wheels. This was to become a design classic and modified versions of the locomotive were built at Swindon until 1888.

Crimea was originally built in May 1855, but this is the replacement built in September 1878

Great Western as a 4-2-2 was basically what the Iron Duke class looked like when they stared to appear in 1847. The weird thing about it from a modern perspective was that those front wheels were not in a bogie or swivelling truck. Rather, they were mounted rigidly in the frame of the engine, the ability to take curves was built into the side-to-side movement of the wheelsets. There were 29 built to this design and Great Western’s conversion made a round 30.

Amazon built in September 1878, photographed at Newton Abbot. The men standing alongside emphasise the enormous size of the broad gauge locomotives

The cylinders were quite large at 18” in diameter. This, combined with a boiler pressure of 100psi* and those huge driving wheels, meant these machines were able to show a fair turn of speed. This performance on Brunel’s railway resulted in performances hitherto unknown. There are several accounts of the engines topping 70mph and a few nearly hitting 80mph.

This really is a ‘Concorde’ moment,** where the speed of travel changed almost overnight. Think of it though – the engines were travelling at these speeds without a cab, with third class passengers travelling in vehicles little better than open wagons with no roof and brakes being something of an afterthought. The originals having just one set of wooden brake blocks on the fireman’s side of the tender. They truly were pioneering days!

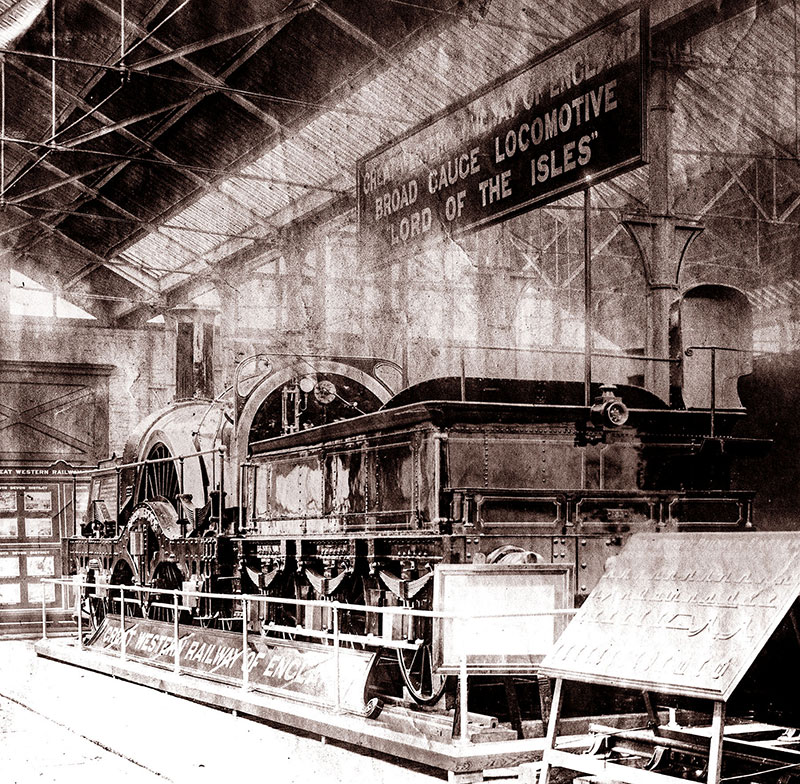

Lord of the Isles was built in March 1851 and after withdrawal in June 1884 was stored at Swindon Works. This photograph was taken when she was on exhibition, either at Edinburgh in 1890 or Chicago in 1893. She was scrapped in 1906

Those tenders were originally capable of holding about 1,880 gallons of water and were full of coke, not coal. A later update was the fitting of larger tenders that held 2,700 gallons and this meant they could go non-stop between London Paddington and Swindon.

It was here that they did some of their best work. May 1848 saw Great Britain on a service heading west from Swindon. As it passed through Wootton Bassett it was doing 78.2mph! The Iron Dukes thus became famous for their speed.

Because of their blistering (for then at least!) speed, the Flying Dutchman service was the fastest train service in the world for many years. One particular driver revelled in his own nickname in the press of the day of ‘Mad Michael’ Almond!. He had an average cruising speed of about 75mph .…

In a fit of nationalistic fervour, seven members of the class built in 1854 and 1855 were named after battles in the Crimean war which was being fought at the time and became known as the Alma class – the name coming from the battle fought at the Alma river in 1854 in the Crimean War.

A few of these engines were rebuilt to become members of the Rover class in 1871. Great Britain, Prometheus and Estaffete were so treated. New frames and boilers (at 140psi) were fitted so little of the originals survived. Under the direction of Joseph Armstrong who was now in charge at Swindon, they were treated to such modern features as a cab. Later locomotives in the class were not straight rebuilds of the originals. New engines, but they did carry their forebear’s names. The Rovers totalled 24 machines in the end.

The Iron Duke replica at Kensington Gardens in 1985

The original Iron Duke / Alma class was withdrawn from service between 1870 and 1884. The three conversions soldiered on until the last went in 1887. By now, the end of the broad gauge was imminent and the Rover class was slowly run down in strength accordingly. The last passenger train hauled out of London Paddington was hauled by one of them. Bulkeley worked a train to Bristol Temple Meads on 20 May 1892. She returned the next morning with a train from Penzance, which makes her the last broad gauge engine to haul a passenger train on the main line.

Sadly, despite her initial preservation on withdrawal in 1884, the last of the Iron Duke class, Lord of the Isles, was cut up alongside the original North Star in 1906. The GWR itself realised its mistake and built a replica of North Star, but only the driving wheels of Lord of the Isles were there to represent possibly the most famous of the broad gauge express engines.

By the time of the GWR’s 150th Anniversary in the 1980s, it was felt that a replica of one of these iconic engines was needed to finally right the wrongs of 1906. This engine was completed in 1985 from the mortal remains of a pair of 0-6-0 Austerity saddle tanks.

The Iron Duke replica at Didcot Railway Centre in 1986, being serenaded by Cholsey Silver Band

Amazingly the new Iron Duke ran in central London outside the Albert memorial and was named there by the then Duke of Wellington. She was operated at a number of venues including the National Railway Museum and Didcot(!) before her boiler certification ran out and even after that, she toured a number of heritage venues. She became a character in the railway series of books and was depicted with bushy eyebrows and a proper Victorian walrus moustache. Ironically not something the real Duke had.

Iron Duke found a long term home with us at Didcot in 2013 and although she is still owned by the National Collection, she fits in very nicely where she is! Although out of ticket, she is a fine representation of a real pioneering age where train travel must have truly been an adventure. An adventure where you travelled across the surface of the earth faster than most people could have ever dreamed of less than a decade before. Historians sometimes call it the railway revolution. They’re not wrong ...

The Iron Duke replica with re-enactors during a Timeline Events photo charter

*Later updated to 115psi.

**7hr to 3hrs across the Atlantic. A feat no longer possible. You have to love progress. I miss that big beautiful white bird .…

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.