Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - January 2024 - Going Loco - January 2024

Going Loco - January 2024

26 JANUARY

Wonderful Winter Wagons: Something Smells Fishy

It’s been a January of specific goods traffic hasn’t it? We’ve done China Clay, Grain and now it’s time to take a deep dive into the piscatorial goods that gave us tadpoles and bloaters and gave rise to one of the most famous stories in the Reverend Awdry’s Railway series – the legend of The Flying Kipper.

Two fish wagons are in the foreground of this scene of broad gauge wagons at Swindon in 1892 after the 7ft 0¼in gauge was finally abolished. Great Western Trust photograph

The movement of fish by rail opened up whole new markets for the trade of this food that we now think of as everyday. Before the railways, the transport of fresh fish was limited by how far you could go before it spoiled. In a world without refrigeration, especially in hot weather, it wasn’t that far. You could of course cure the fish in salt or some other preservative, but that’s just not the same as having the fish fresh.

A Tadpole fish wagon with guard’s compartment in the centre. Photograph: Trainiac by Creative Commons

It was the fast, cross-country nature of the railways that first made the transportation of fresh fish possible to consumers a long distance from the port of capture. Thank the railways for the proliferation of your fish and chips country wide for example. Of course, having your fish bump along in the 25mph unfitted freight trains of the steam era kind of negates the advantage of fast moving fish traffic, so even in the earliest days of specialised GWR fish wagons, they were fitted with larger diameter wheels and vacuum brakes. This meant they could run at passenger train speeds.

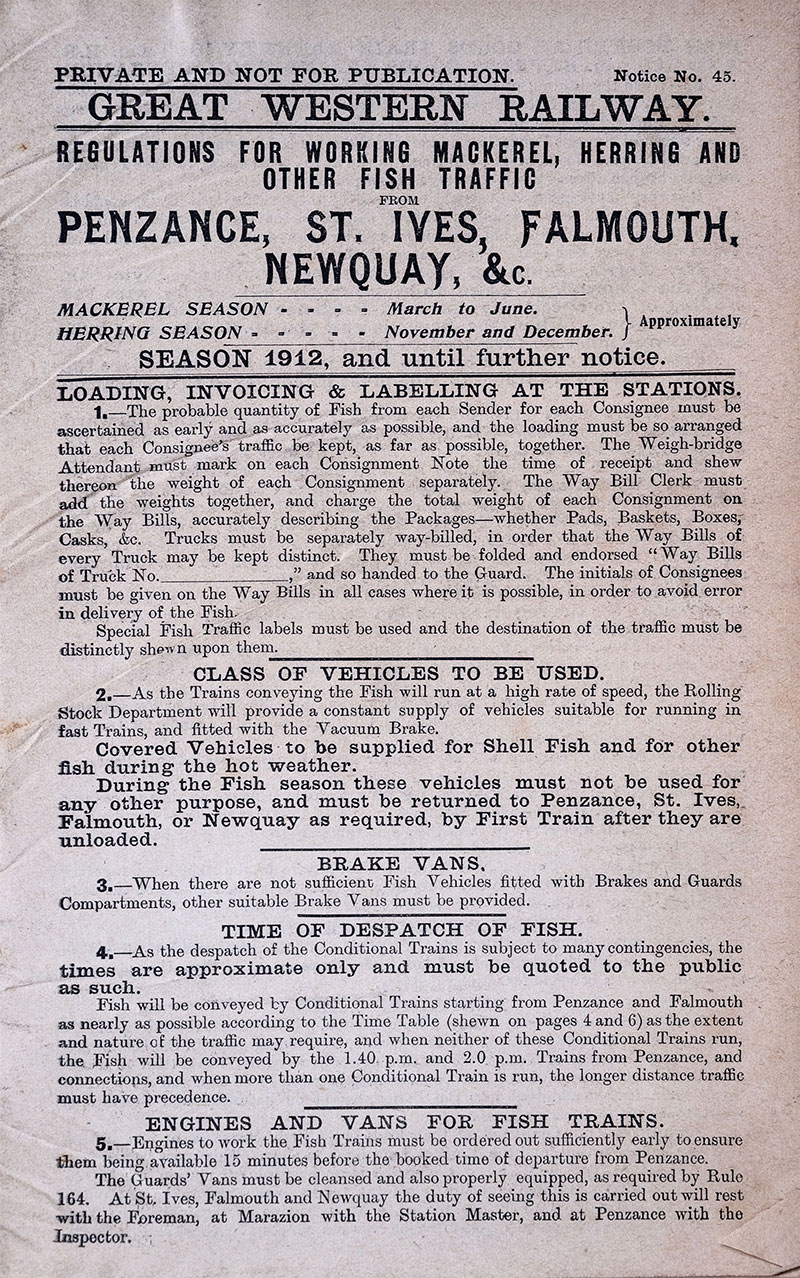

Front page of fish traffic regulations, 1912: note section 3 which refers to fish vehicles fitted with brakes and guard’s compartments. Great Western Trust collection GWT/2015/D.15

Separate vehicles were needed of course because of the smell. This meant that they were invariably coupled at the rear of the train so the smell was wafted downwind of any passengers that might be in the coaches. The surprising thing about these wagons was that they were open wagons, not covered vans. The fish was packed in barrels or boxes with either salt or ice. These open fish trucks were quite large affairs. They were built like coaches and indeed were converted old coaches in many cases. They could be six wheeled or even eight wheeled with two bogies. Being built on old chassis, there wasn’t a huge amount of standardisation in the designs.

Bloater A No 2123 fitted with both air and vacuum brakes for through traffic over other railway companies. Photograph: Phil Kelley collection

These were odd vehicles for many reasons. The weirdest being that some of them contained a guard’s compartment in the middle of the wagon. Quite what this did to the olfactory well-being of the poor guard was not recorded but given that some of the old coaches were brake coaches, it made perfect sense to maintain all the equipment in there and box over to provide a shelter for the guard. These bizarre specimens were given the telegraphic code TADPOLE. This name was later applied to all the large open fish wagons. This rather motley collection of vehicles was present in both the broad gauge and the later standard gauge Great Western and have a hugely complex history in which some of the wagons were re-gauged from broad to standard, some shared diagram numbers as scrapping or reorganisation occurred. This is far too much for a Going Loco blog so I think we’ll turn out the light on the TADPOLES and quietly back out of the room .…

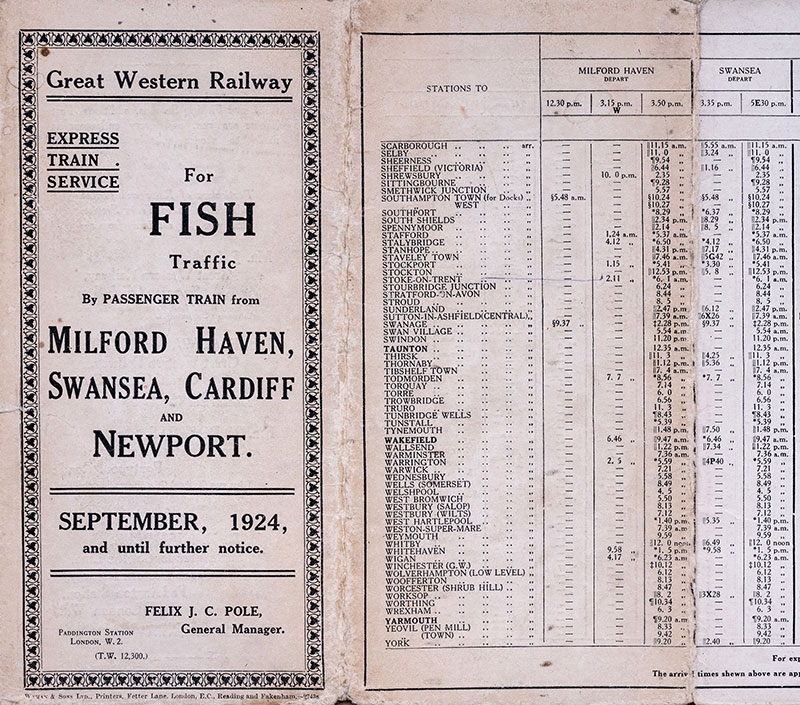

A part of the timetable for fish traffic by passenger train from South Wales ports to destinations around Britain, September 1924. The whole document unfolds to 16 inches square and lists arrival times at 250 stations. Great Western Trust collection GWT/GWS/3761

Fish vans didn’t happen on the Great Western until 1909. These early fish vans were smaller vehicles that looked not unlike the equivalent MINK four wheeled covered goods vans being developed in the same era. The beginning of the longer wheelbase fish vans happened during WWI. These had all the features that were to be seen on the later vehicles. There were step boards so you could climb into the van from the ground. You had sliding doors to allow easy and fast access. Time was freshness don’t forget. They had roof ventilators instead of the end ventilators of the MINK style wagons. They became known as BLOATERS.

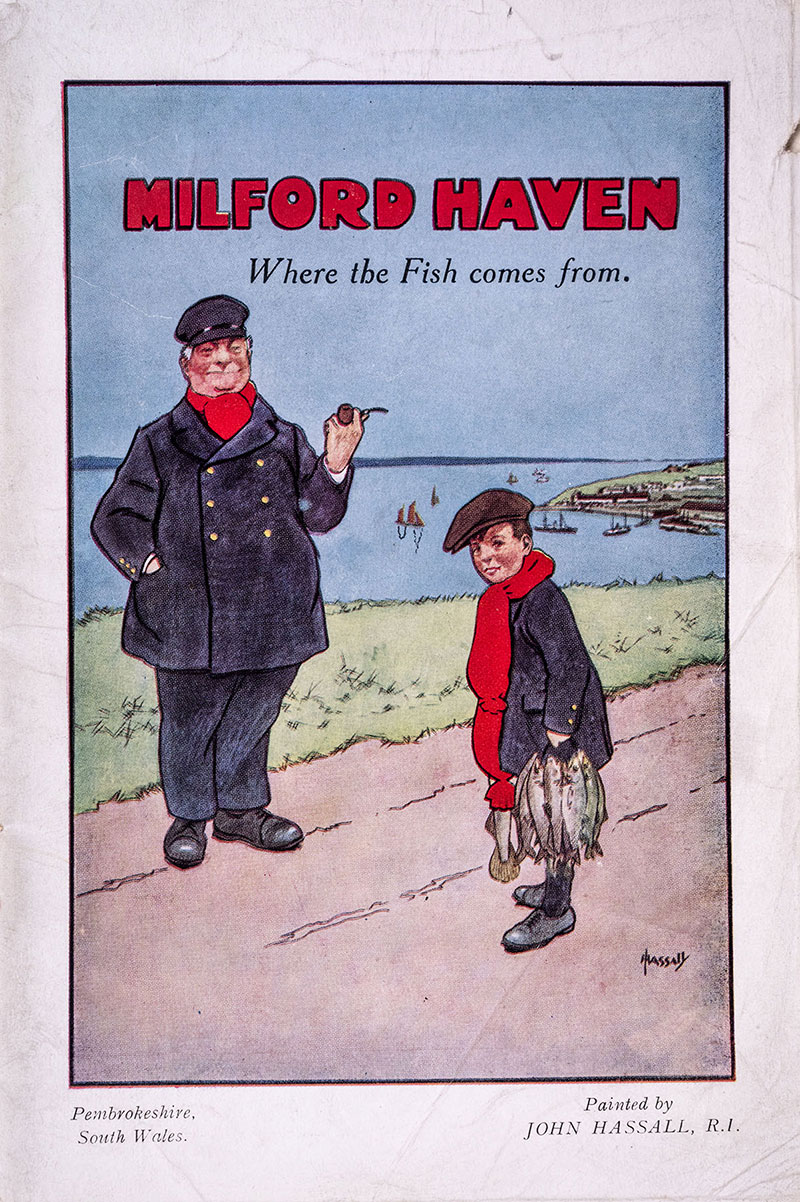

Cover of booklet published 1927 by the GWR: Milford Haven Where the Fish comes from; 32 pages. Great Western Trust collection GWT/GWS/1429

The one we have on site at Didcot is again owned by the GWR 813 Preservation Fund. No 2671 is a member of about 50 vehicles that were built to diagram S10. The lot number was No 1356 and they were built between 1924 and 1926. The S10s are quite typical of the later vans. Although four-wheeled, they are 28’ 6” long which puts them in the longer side for this type of vehicle. They had six sliding doors arranged three on each side and of course were fitted with vacuum brakes and 3’ 2” diameter wheels to enable them to travel at express speeds. The buffers were of the self-contained type which meant that the shaft of the buffer didn’t protrude behind the buffer beam when compressed, leaving more space for structures and equipment behind them.

Photograph of fish train published in the Milford Haven Where the Fish comes from booklet

The fish traffic from the West Country had steadily been declining from the start of the 1930s. As a result, an increasing number of the fish carrying vehicles sought other employment. Their ability to be put in passenger and fast freight trains meant they were (presumably once thoroughly washed!) in demand for other services. Luggage and parcels were obvious starting points but a whole panoply of different tasks were eventually taken on.

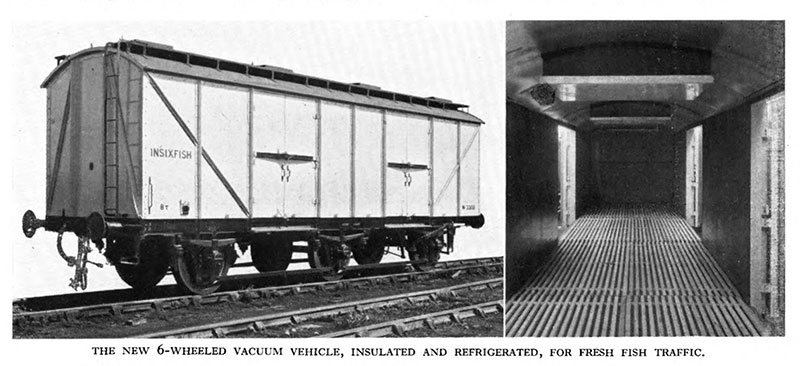

The INSIXFISH wagon introduced in 1947. Photographs published in British Railways Western Region magazine, December 1948

The last design of fish wagon was a bit of a curve ball. The INSIXFISH was a novel vehicle that had many innovations incorporated into it. They were six wheeled (the clue is in the name!) and were also insulated (also in the name) and refrigerated with dry ice for the first time. Wooden slatted racks were fitted inside for the crates of fish to sit on and allow the cold air to circulate. There were only two pairs of doors a side and strangely they opened on hinges. There were ladders at the ends of the vehicle and these were there to allow workers to climb up onto the roof and fill the refrigerant tanks with dry ice (solid CO2). The diagram S13 wagons were ordered by the GWR but only appeared right at the end of the company’s existence in 1947.

Bloater 2671 awaiting restoration at Didcot

Fish traffic is a largely forgotten traffic on the railway but its historical significance in broadening the diet of the nation cannot be underestimated. In an age where we can buy food from all over the world in our local supermarkets, we forget just how limited people’s diets used to be early in even the nineteenth century. It’s just one more reason why we should be incredibly proud and indeed grateful for what the railways have done for us. It’s a bit like that line in Monty Python’s Life of Brian isn’t it?. What have the Romans (railways) done for us? Well, apart from allowing the masses to move about, keeping the follow of goods moving at peace and war, the fish and chips, etc, etc, etc .…

FRIDAY 19 JANUARY

Wonderful Winter Wagons – Engrained History

We took a look at the China clay traffic last time and this time we will look at something different. Although, just the one blog on this. I’m not going to turn it into a cereal .…*

The transport of farm goods goes back to the earliest days of the railway. Here on Going Loco we have discussed the long (although now-ended) traffic of milk on the Great Western. There were a few other bulk farm goods that were transported by rail and indeed have been until relatively recently.

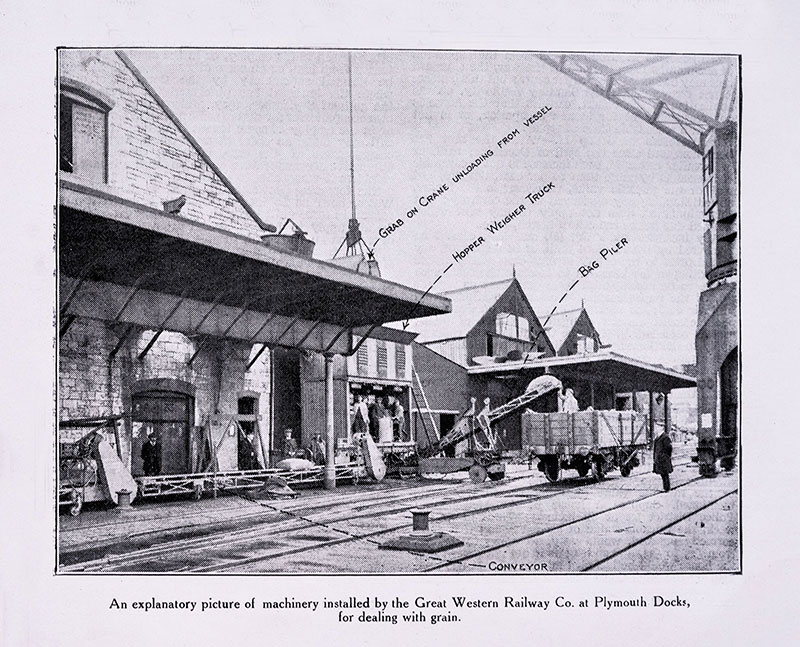

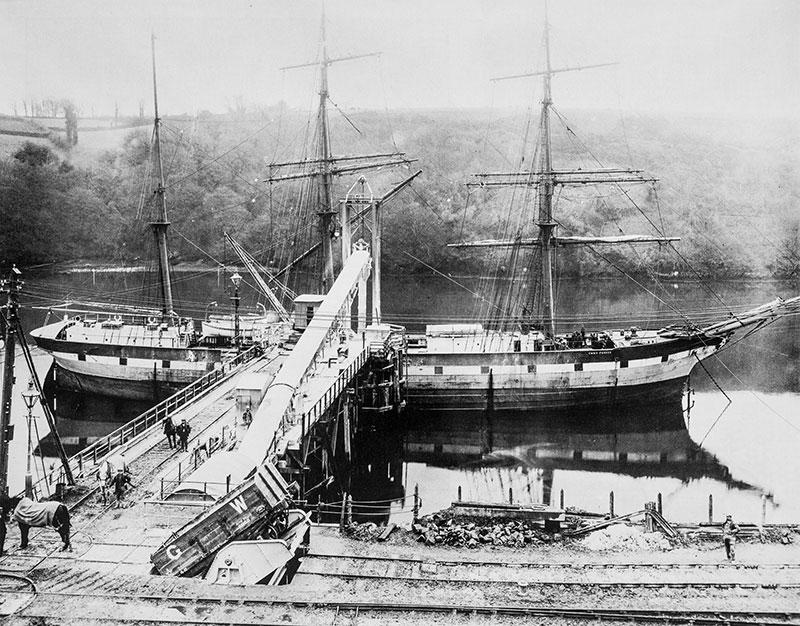

The May 1919 edition of Great Western Railway Magazine included this photograph of machinery at Plymouth docks which automatically weighed grain and put it into sacks before being loaded into open wagons

Grain has always been a staple of the human diet and its cultivation part of the very bedrock of civilisation itself. It is convenient because unlike many other foodstuffs, it is quite durable and as such can be harvested mechanically and stored for long periods of time. This means it can be used to bridge over lean times and keep people alive. Its transport and trade has also been a large part of human history too.

The Great Western, like many railways, transported grain in all sorts of different vehicles, mainly in sacks. It was common practice for grain to be carried either in open wagons that were covered with tarpaulins or the ordinary MINK covered vans. The turn of the twentieth century saw the continued increase in industrialisation and mechanisation and small containers like sacks were no longer the ideal solution. They needed to think bigger and this was done initially by not accepting that dedicated grain vehicles were required.

No 42239 as built with heavily-framed side doors

What, I hear you say? Well, yes, it’s a bit weird but the G W R was a bit reticent to make vehicles that were entirely dedicated to the traffic of grain. They did not carry a huge amount of this type of traffic so dedicated vehicles were possibly seen as a waste of money. The story of these wagons begins in 1905 when an experimental 20 ton van was built. This van was given the diagram number V10, placing it in the wider diagrams of covered goods wagons. What made No 47728 unique for the railway was that it had a sliding hatch in the roof and angled false floors that created a chute type affair inside. This turned the van into a hopper type design that could be rearranged with the false floors repositioned, to become a standard goods van.

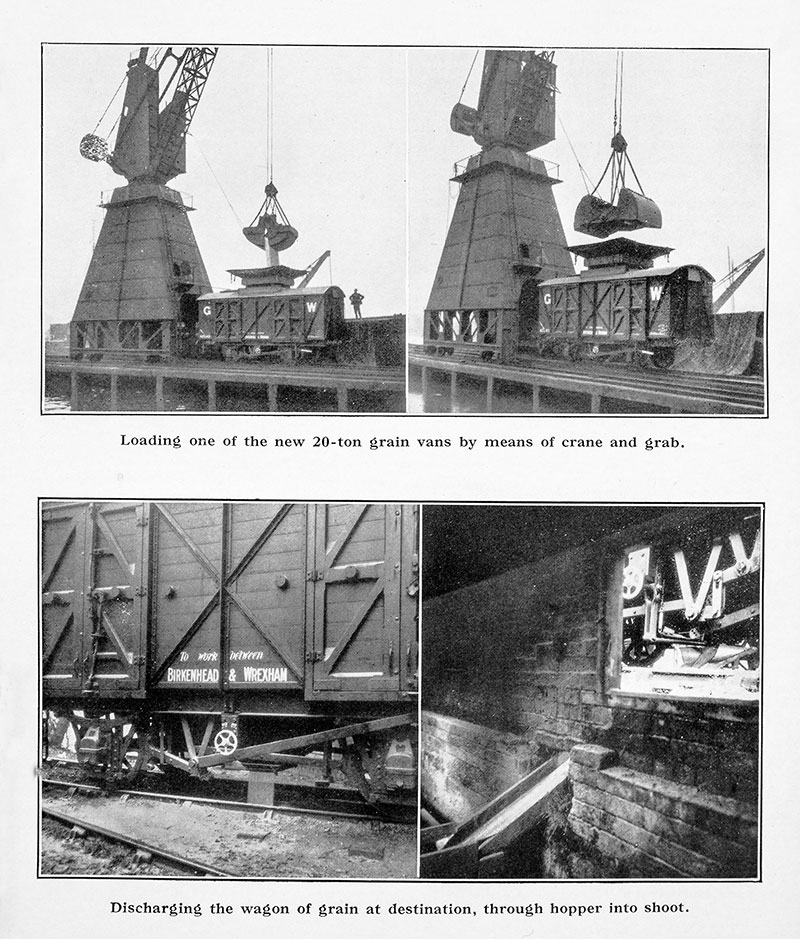

These photographs of grain wagons being loaded by crane and discharged through the hopper were published in the Great Western Railway Magazine, June 1928 edition

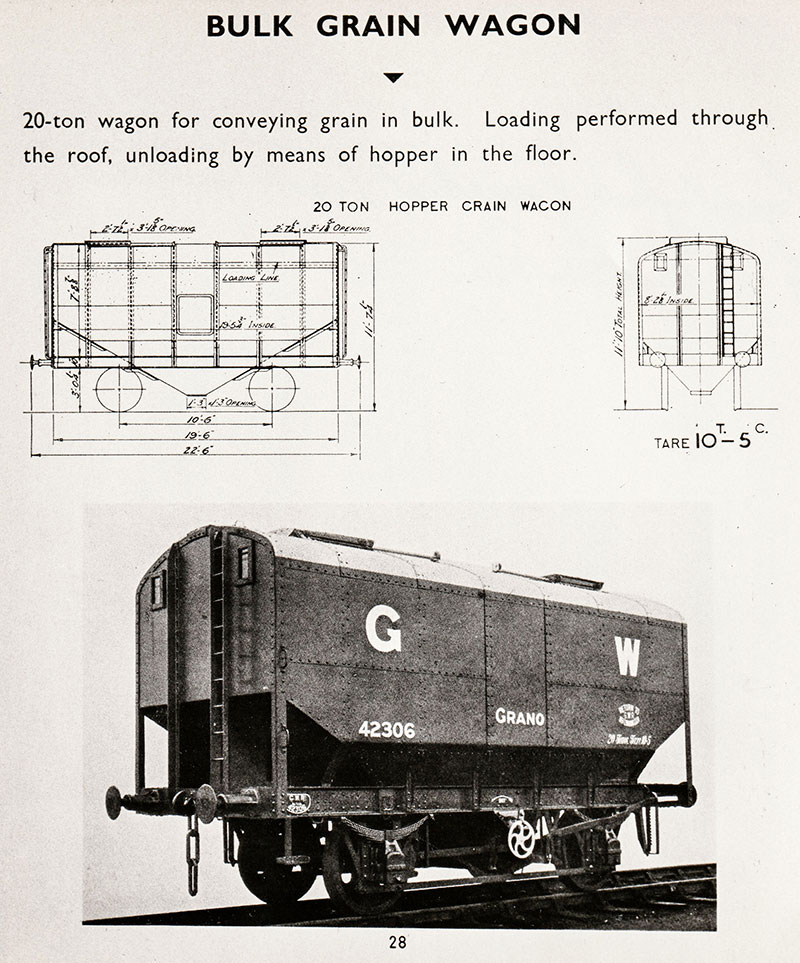

There was to be a small fleet of these vehicles built, but strangely that went to the wayside and the bulk transport of grain wasn’t thought about again until after the Great War. 25 standard 16ft goods wagons were modified to ‘make necessary alteration’ so they could carry grain. In 1925, the next move was to convert some diagram O25 OPEN A 12 ton open wagons with the fitting of some hoppers and presumably a sheet rail so a tarpaulin could be fitted to keep the load dry. The next move was to go back to the convertible van idea.

The V20 convertible grain van is where the connection with the collection at Didcot comes in. It’s a bit of a weird and complicated one too. The idea of being convertible is weird to start with but it was an odd size too. There were plenty of standard sizes available but an unusual 10ft 6in wheelbase version was used instead. This took the automation of grain transport further in that there was an opening hopper bottom to the van too. This was in concert with the opening roof.

A diagram V20 wagon after conversion back to carrying grain, now with no side doors

This meant that loading from the top via a crane and grab and emptying from underneath using a conveyor belt became possible. The doors were built very sturdily as the force that the 20 tons of grain could impart on them was quite large. The van also has two small windows in the ends and this enables you to see if the van is loaded or empty. Suitable steps and handrails were also supplied to get you up there to peek in! The example at Didcot is a very rare survivor and is No 42239, built in 1927. It is part of the impressive freight collection amassed by our friends in the group that owns and operates 0-6-0 saddle tank locomotive No 813. No 42239 is probably the only survivor of the 12 Diagram V20 vehicles built. The vans were used to transport grain between the port at Birkenhead and Cobden Flour Mill at Wrexham.

This description of the Grano hopper was published in a GWR brochure illustrating wagons for special traffics

This didn’t last long and they were converted to carry bulk cement from the Bristol Channel Cement Co. The reason for this was the fact that the traffic they had been built for had ended. They gained a new galvanised steel liner to protect the wooden structure. Swindon gave them a new diagram of V29. The idea of convertibility was abandoned at this point and the doors were screwed shut. They were converted(!) back to transport grain traffic again (and re-diagramed back to V20 – I told you this was complicated .…) in the summer of 1939, with our example – No 42239 – being noted as the first. The new conversion gave them all new sides without doors this time.

No 42239 currently in use as a store behind the carriage shed at Didcot

The other vehicles that were developed were the famous GRANO hopper wagons that were basically a steel bodied purpose built hopper version which was slightly shorter that the V20s. These 12 wagons began construction in 1935 and were given the diagram No V25.

No 42239 has been something of a chameleon throughout its life, changing its look several times but the wagon has gone on. Clearly the traffic was never massive as the wagons were built in such small numbers but the grain wagons hold their own unique place in the history of the Great Western Railway freight pantheon.

*I apologise for this and I’ll get my coat .…

FRIDAY 12 JANUARY

Wonderful Winter Wagons – Me Old China!

Well, here I go again on my own*. Going (Loco) down the only (rail) road I’ve ever known**.

That’s enough of that .…

Which is a round about way of saying that it’s the start of a whole new year of scribblings from your man on the ground for Going Loco. As is traditional, we will start the year with the unsung freight moving heroes of the collection – the wagons – and you don’t get any more unsung or humble than a 4 wheel, 5 plank open wagon.

A William Cookworthy mug, limited edition produced by English China Clays

Unlike many of our Going Loco stories, this one starts in the Far East! Kaolinite or china clay was first used in China well over ten thousand years ago. It is a rare type of decomposed granite, finer than most talcum powders, that arises naturally. Its use was of course in the production of fine white ceramics like porcelain. These became highly sought after products in Europe, where nothing of the sort had been seen before. Now, transporting delicate goods thousands of miles, back in the eighteenth century, was clearly something that was both tricky and expensive. It was something only the very wealthy could afford.

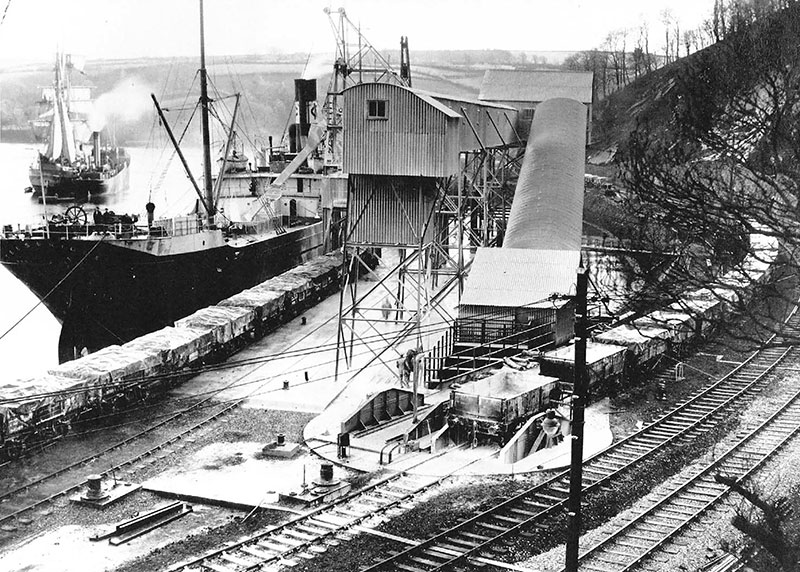

No 4 jetty at Fowey in 1910 showing the new conveyor and a wagon being tipped into it. This made it possible to increase the rate of shipment from 200 to 300 tons a day to 200 to 240 tons an hour. Horses were still used for shunting

Enter into this scenario a genius from Plymouth by the name of William Cookworthy. He was born in April 1705 and became one of those figures in the early industrial revolution that was a leader in several fields of technology. He was a noted pharmacist and chemist. He was also partly responsible for the development of hydraulic lime with John Smeaton which enabled the construction of several lighthouses. A type of artificial ‘glassy’ porcelain was already being produced in Britain at the time in places like Bow, Chelsea and Derby but the real thing still eluded the UK ceramicists.

No 8 jetty at Fowey was opened on 27 September 1923. This photograph show Lord Mildmay performing the opening ceremony with a gathering of principal officers of the GWR

Cookworthy took on this problem in the early 1740s. He had access to the writings of French missionary Père Entrecolles, who had visited China and noted the processes used, to guide him. He set out to see if the raw materials to make porcelain were present in the geology of the British Isles. He spent a great deal of time travelling across Devon and Cornwall and eventually he found them near St Austell. It took a further twenty years for him to perfect the recipe .… In the mid to late 1760s, he used this discovery to found a porcelain factory in Plymouth – the first of its kind in Britain. It was eventually moved to Bristol and sold, but he had laid the foundations of a huge industry.

A general view of No 8 jetty

Kaolinite turned out to be a wonder material and its use in ceramics was just the start. It is used in huge amounts in the paper, pharmaceutical and many other industries. So what on earth has this to do with the Great Western Railway? Well, the mines were in Great Western territory! Therefore it was natural that the Great Western would want it as goods traffic. An extensive network of small branch lines built up around the china clay deposits. Facilities to powder the clay known as ‘dries’ were common along the routes and these all fed towards the port. Fowey became a hub for the export of china clay and an extensive facility for the movement of kaolinite from railway wagons to ships was developed.

An elevated view of No 8 jetty. It was constructed at an angle to the shore so that vessels could moor alongside for its entire length

There were also wagons developed specifically for this trade. Although it was originally carried in barrels in open wagons, the idea of simply filling the wagon up was clearly more attractive. As luck would have it, china clay has a mass to volume ratio of about 1 ton to 28 cubic yards. The perfect full load for a ‘standard’ five plank open goods wagon. The use of an opening end door to allow the material to tip out completed the design. The wagons were placed on a pivoting platform that was sited next to a jetty. The end door was unlocked, the platform was tipped and the contents were dropped onto a conveyor belt that transported the material into the hold of an awaiting ship. There were several of these jetties on the quayside.

No 92943 preserved at Didcot

These wagons date way back into the history of GWR goods vehicles. One of the earliest identified open wagons from the company is indeed a china clay wagon. This means that a fleet of these wagons was in existence long before the outbreak of the First World War. Just before the Great War, renewals in the fleet were being considered. Various types were introduced but the type that became the standard was the diagram O13. We have a representative of this type at Didcot - No. 92943. These were built from 1913 and ours is one of this early batch. There were 500 of them built – giving an idea as to the scale of the operation.

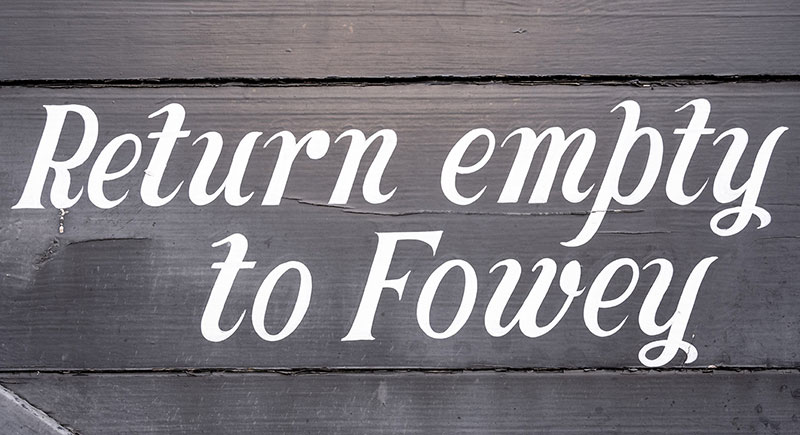

Detail of the ‘Return empty to Fowey’ lettering

The end door on No 92943

Detail of the end door fastening on No 92943

They were modified several times in their lives and were given upgrades to their brakes and various other details. One thing that was discovered was that the clay would rot out the floor planks. To combat this, zinc sheeting was applied to the floor of many of the wagons. As the clay was in powder form, keeping it dry was of paramount importance. A steel rail was fitted so that a tarpaulin could be spread over in a ‘roof’ shape to keep the rain off. British rail built another batch of wagons to a very similar pattern in the mid 1950s and these types were operating well into the 1970s. The china clay traffic is still alive and well and the United Kingdom is still a major producer. It’s nice to see a continuity of industry dating back so long and yet still relevant in the modern era. One also represented with us here at Didcot.

* Except for the whole Going Loco team of course.

** With sincere apologies to Whitesnake.

FRIDAY 5 JANUARY

The Pioneer's Progress - Part 10

A bleary eyed blogger turns the lights back on at Going Loco headquarters. An email awaits .…

What do you mean “I’ve got to get on with writing Going Loco again”? Is it that time already? What do you want me to write? Nothing? It’s a new year update on No. 1466 from our roving reporter, Phil? Well, in that case, take it away good sir .…

Thanks, Drew!

Well, it’s a short-ish update this time round .... But nevertheless progress! As I write this, Ryan and his team at the West Somerset Railway are wrapping up the work before the Christmas holidays. Looking back, it’s difficult to comprehend just quite how much has gone on but all in all, it’s fair to say it’s been a very busy year and we’ve overcome and achieved a great deal on 1466, and next year is set to be very fruitful. Since my last update and after a short delay in the delivery of rivets, the inner firebox is now fixed back in its rightful position within the boiler. Having previously had British Engineering Services (BES) sign off the alignment, it’s all now thankfully been riveted back together.

Ryan Pope knocking down the foundation ring rivets. Photograph by Phil Morrell

The new palm stay brackets have also been fitted and riveted into place along with the new palm stays themselves being fitted. The steam collector and its associated pipework are currently being re-fitted back into the boiler.

Josh Chivers taking a fresh white-hot rivet out of the forge. Photograph by Phil Morrell

A full set of boiler tubes (all 195 of them!) have been ordered and delivery is anticipated by mid-February 2024. Having previously sourced all the required material for the crown-stays and side-stays earlier in the year, we are now currently putting together orders for the manufacture of them.

The big question is on your lips is clearly, ‘What does 2024 hold?’

Matt Healey placing the rivet from the inside of the firebox. Photograph by Phil Morrell

The new year should see the stays being manufactured. The lads at WSR will be spending quite some time (quite some weeks in fact!) drilling, reaming and tapping the firebox ready for the fitting of the crown and side stays once they arrive back from the machinists. Then the longitudinal stays will be refitted and then so will the boiler tubes. Exciting stuff!

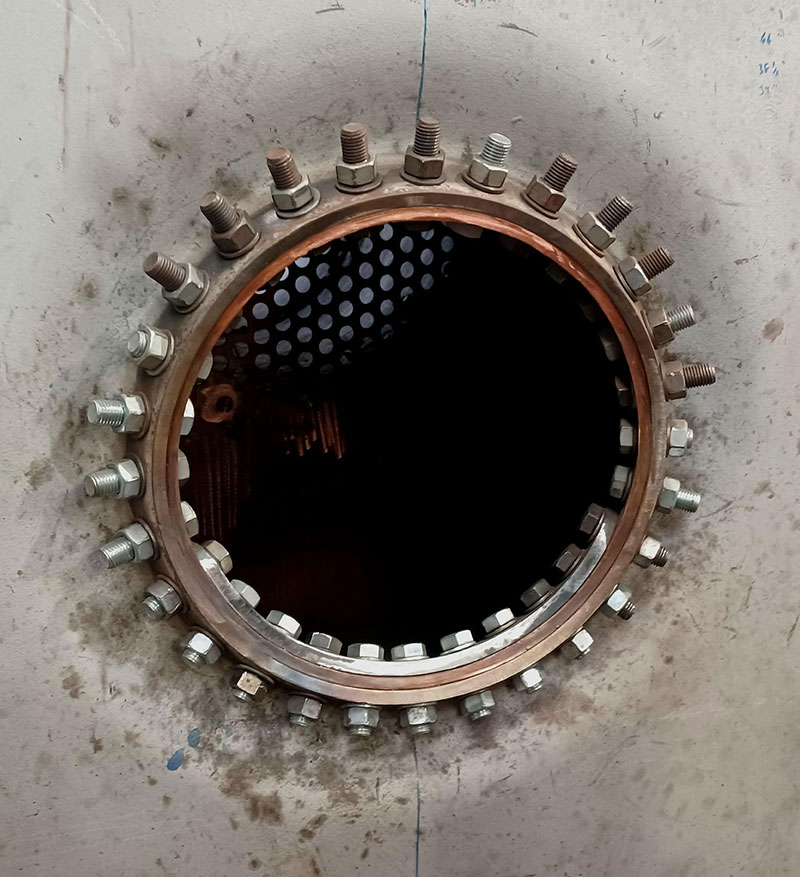

A view of the inner firebox and water space in the boiler – a view not often seen. Photograph by Phil Morrell

The chassis will also be entering the paint-shop in the new year to make a start on preparations for its final livery to be applied. Seeing as the mechanics and chassis of 1466 have previously been completed, it should, in theory produce a quick-ish turn around, once the boiler has had its official hydraulic and steam test examinations.

The firehole door ring all bolted together prior to riveting. Photograph by Phil Morrell

That once ‘far off horizon’ can now been seen clearly in sight and is drawing closer day by day. So watch this space. And, with that, it’s back to the studio .…

Cheers Phil! Well, I hope that was a nice new year’s present for everyone! That’s great news to hear that our little pioneer, the engine that started it all, is well on the way to coming home. What a great start to 2024!

Back to the beginning at Didcot – 1466 in the ash shed in 1968

|

|

|

|

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.