Tuesday Treasures

BLOG - Discover fascinating hidden gems from our Museum and Archive

We are very fortunate indeed here at Didcot Railway Centre with our vast collection of historic locomotives, artefacts and memorabilia that forms our world-famous museum telling the story of the Great Western Railway and its employees. For our volunteers and staff there are objects of great interest everywhere around the centre, each item unique to keeping the greatest railway company on the rails.

Our Tuesday Treasures blog is designed to share this vast and historically important collection so enjoy our deep dive into the rich history in our Museum and Archives.

Latest Blogs

TUESDAY 30 APRIL

Children’s Education through Railway Publications - Part 5

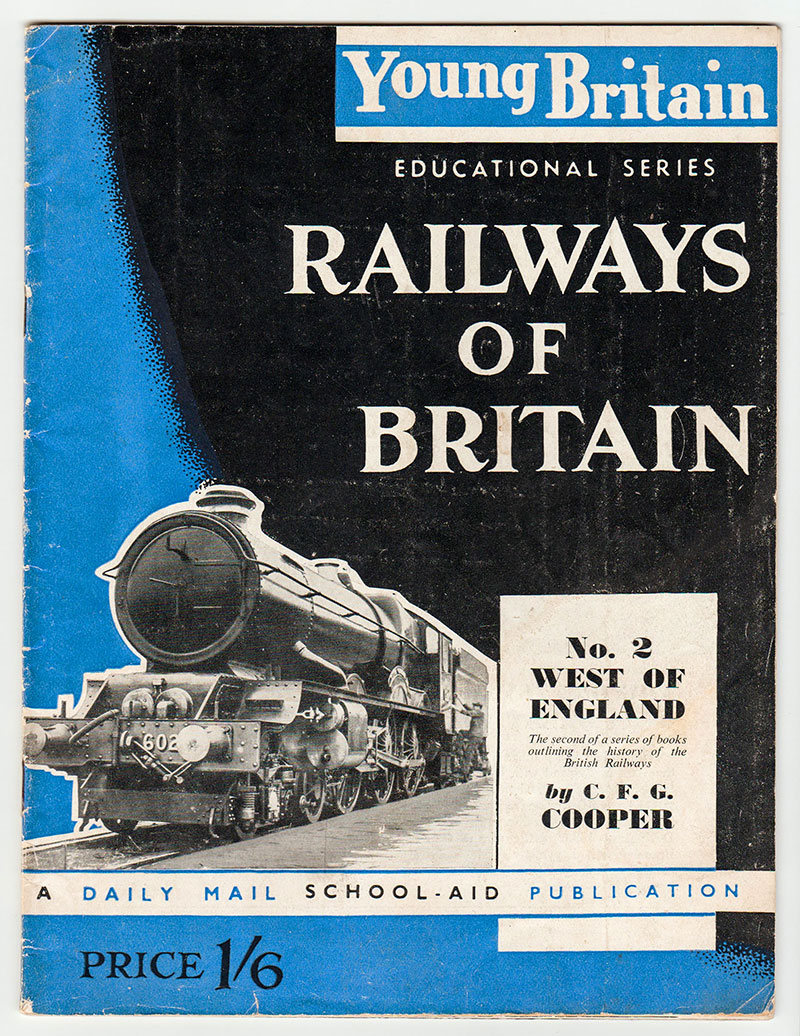

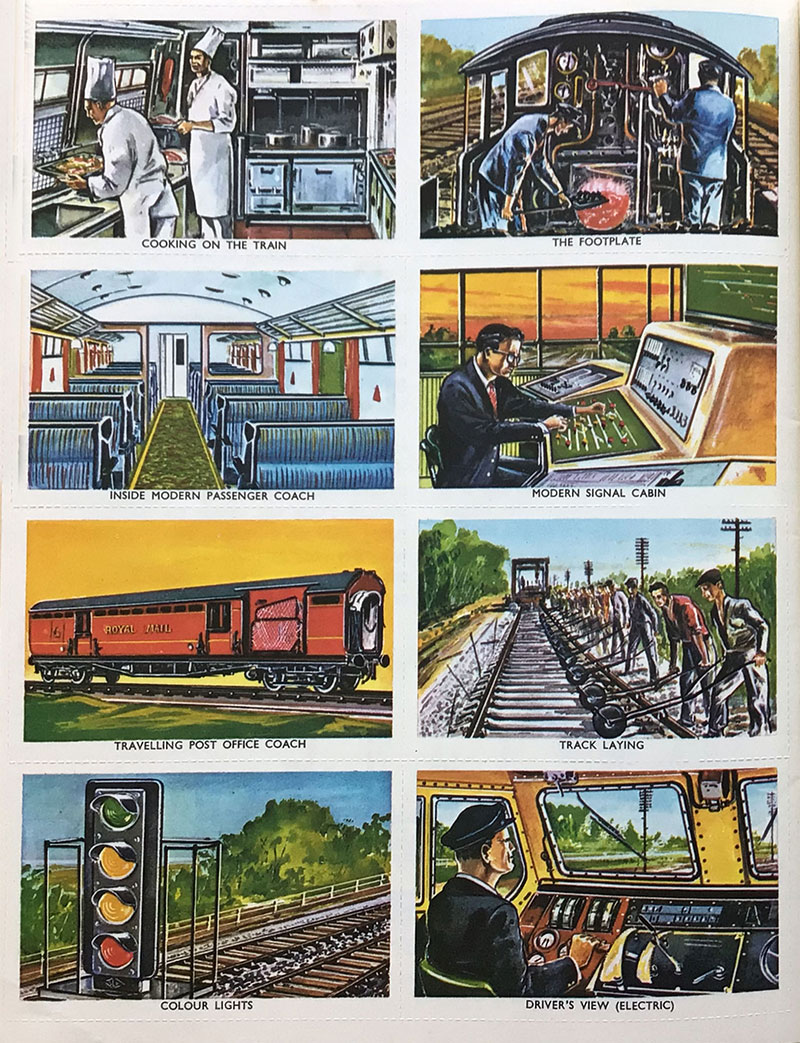

In four previous blogs on this subject we have recorded how the Great Western Railway produced children’s books and games that provided their image and gave varying degrees of educational content. The Great Western Trust collection, also holds a wide variety of that material of the British Railways era, both railway-produced and that of a contemporary publisher. Our Blog today focuses upon a series produced by the Daily Mail entitled ‘Young Britain Educational Series – Railways of Britain’ The price was one shilling and six pence (7½p in today’s money).

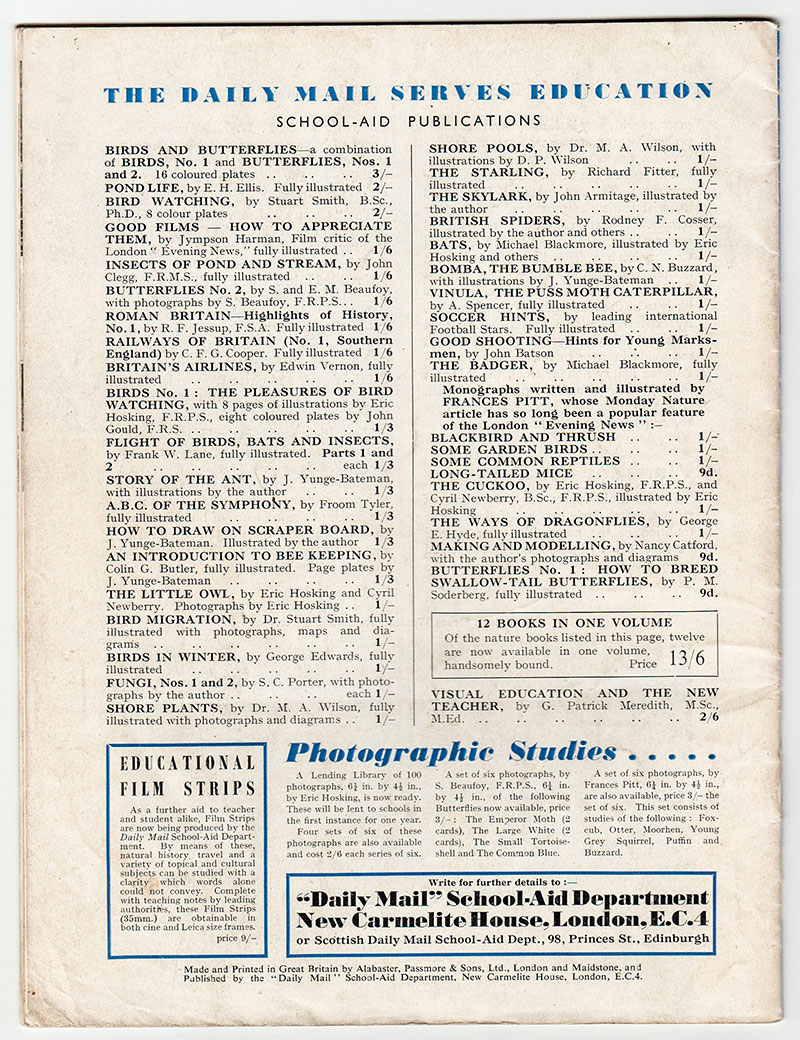

For a national newspaper this was quite an undertaking and not done lightly given the wide breadth of the subjects of interest to youngsters, beyond the railway edition featured today.

In fact the one we illustrate, quite naturally as it has a GWR King Loco on the cover, was No 2 of a series which began with the Southern Railway. It is an in depth study of the GWR right through to the very early years of Nationalisation extending to 32 pages. No doubt the then BR(WR) publicity department must have provided images and general information to ensure the contents were accurate. However, we can find no precise publication date but believe from its contents its around 1950. If readers of this Blog have editions other than Nos 1 & 2 which we hold, or know their publication date, we will be pleased to hear from them.

To prove our comment on the wide range of subjects this ‘Young Britain’ series covered, we illustrate the advert on the back cover of the GWR focused edition.

What chance of today’s newspapers producing such wide ranging subjects in a contemporary setting for our current ‘Young Britain’ ?

TUESDAY 23 APRIL

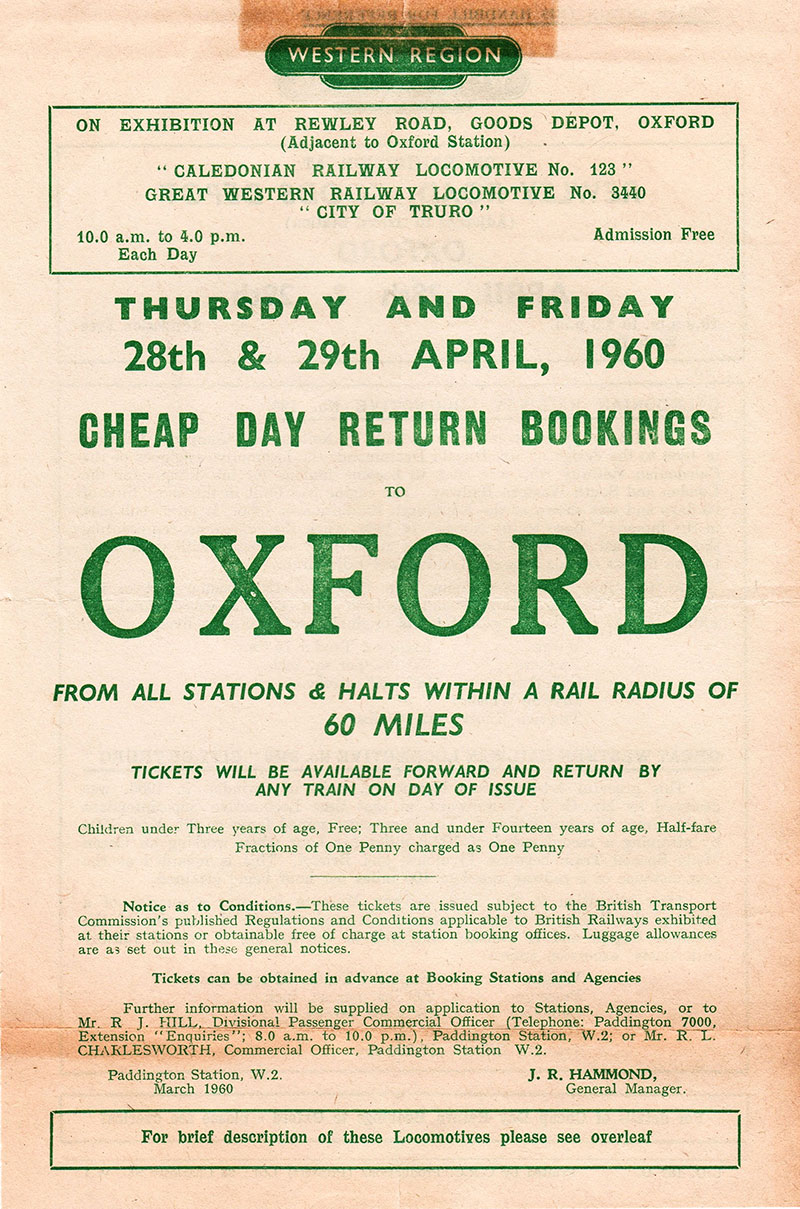

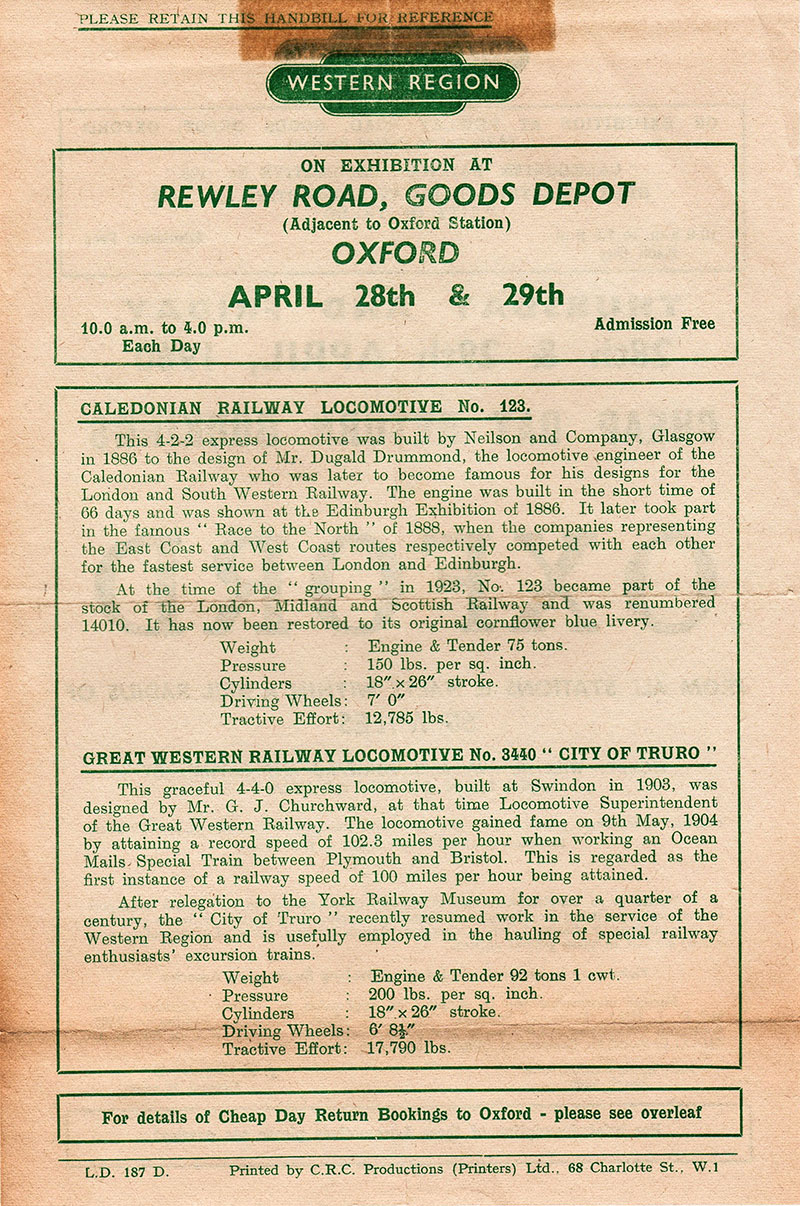

A Special Exhibition

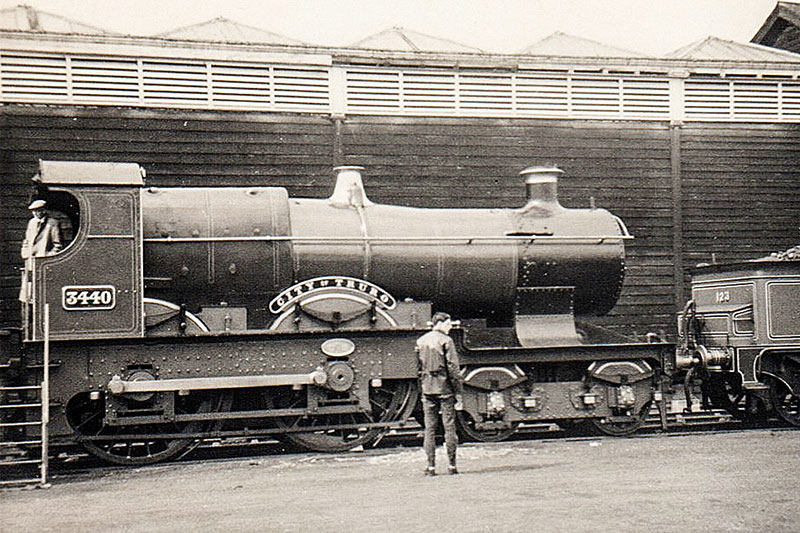

From 10 am to 4 pm each day on Thursday and Friday 28 and 29 April 1960, some 64 years ago, BRWR held an exhibition of 3440 City of Truro together with ex Caledonian Railway loco No 123 at the Goods Yard in the ex LMS station at Rewley Road Oxford.

Today’s Tuesday Treasures illustrate the special handbill publicising the free entry event and photographs taken by a visitor, which are now in the Great Western Trust collection.

Tuesday Treasure readers may recall that in September 2023 we blogged about the special train pulled by City of Truro in September 1957 from Plymouth to Penzance, again organised by BRWR specifically for so called ‘Railway Enthusiasts’ just like this 1960 event.

The photos are a little soft focused, reflecting of their time the affordability of cameras and film and its development, far away from the smartphone of today, and involving an anxious wait for their return from the printers to see whether any were good, out of alignment or overexposed. No chance in those days of immediately checking the image!

An overall view of the LMS Rewley Road station in the 1940s or early 1950s. Carriages at the GWR station can be seen on the left

As illustrated, the handbill is helpfully double sided, to include key information about both locomotives. How many folk took the opportunity to visit the exhibition is a mystery, and it’s fair to consider the effort BRWR went to to event clear the yard and create the whole event, and why Oxford?

Rewley Road station decorated for the Festival of Britain in 1951

Of course whilst both locomotives are now in museums, the Rewley Road station building has itself been wonderfully saved, restored and is a central attraction at the Buckinghamshire Railway Centre. Perhaps by serendipity, that the exhibition event was held at Rewley Road drew sufficient focus on the imminent demise of the ex LMS Oxford Station that saving it was brought to the attention of the authorities?

TUESDAY 16 APRIL

Westbury Refreshment Rooms

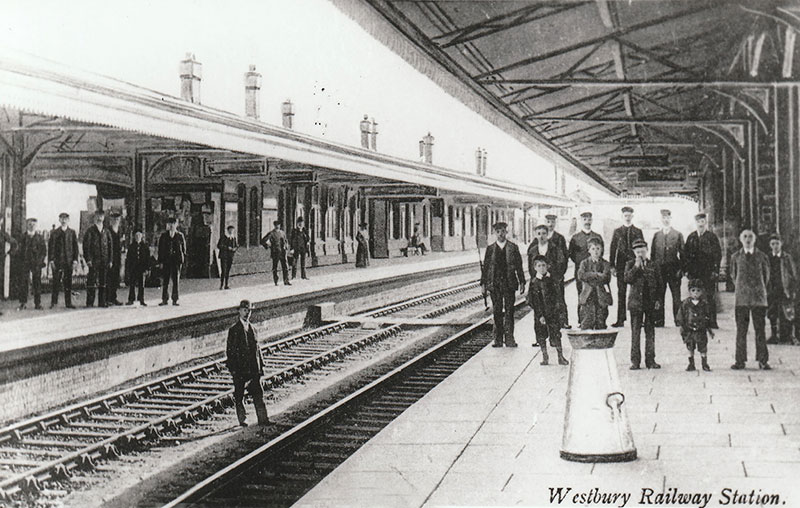

A view of the rebuilt Westbury station when very new, with station staff lined up for the photographer. Photograph from the Jeffery Collection, Great Western Trust

Westbury (Wilts) was first served by the railway from Thingley Junction on the original Great Western Railway main line in 1848 when, on 2 September, a special train driven by Daniel Gooch and assisted by I K Brunel arrived there from Bath. The line opened to the public three days later and over the following decade Westbury became a railway crossroads served by trains from Bath and Chippenham to Salisbury and Weymouth.

Another early view of the 1900-built station, showing its four platforms. Photograph from the Jeffery Collection, Great Western Trust

In 1900 the opening by the GWR of the Stert & Westbury Railway placed Westbury firmly on the new short route from Paddington to Plymouth and its importance grew accordingly. Coincident with this the GWR built an impressive new station to cater for the increased traffic, consisting of four platform faces and much enlarged passenger and goods facilities.

This potted history of the railways around Westbury brings us to this week’s Treasure. When the station was modernised in the 1970s this superb stained glass mosaic window was rescued and donated to the Great Western Trust in 2003. It depicts the GWR coat of arms and although we are unsure of its exact location we know it came from the new (1900) Refreshment Rooms that were located at the London end of the down island platform.

The stained glass GWR coat of arms from the Westbury Refreshment Room, now conserved and displayed in the Museum at Didcot Railway Centre

The window measures 19” x 21”, has been professionally conserved and mounted in an oak frame. It is backlit and is on display in the Trust Museum. Please visit us and see for yourself what a treasure it is.

A general view of Westbury Station from the road bridge at the north end of the station in the 1950s. Great Western Trust photograph

The Down side island platform in the 1950s. The Refreshment Room was located adjacent to the ‘Telegraph’ sign. The ‘Westbury’ running-in board is now a Western Region enamel sign. Great Western Trust photograph

The 1pm train from Salisbury to Bristol of just two coaches has paused at Westbury on 20 July 1963 behind No 6954 Lotherton Hall. The ‘Telegraph’ sign in the previous photo has been replaced by an enamel one reading ‘Telegrams’. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

TUESDAY 9 APRIL

A Special Event

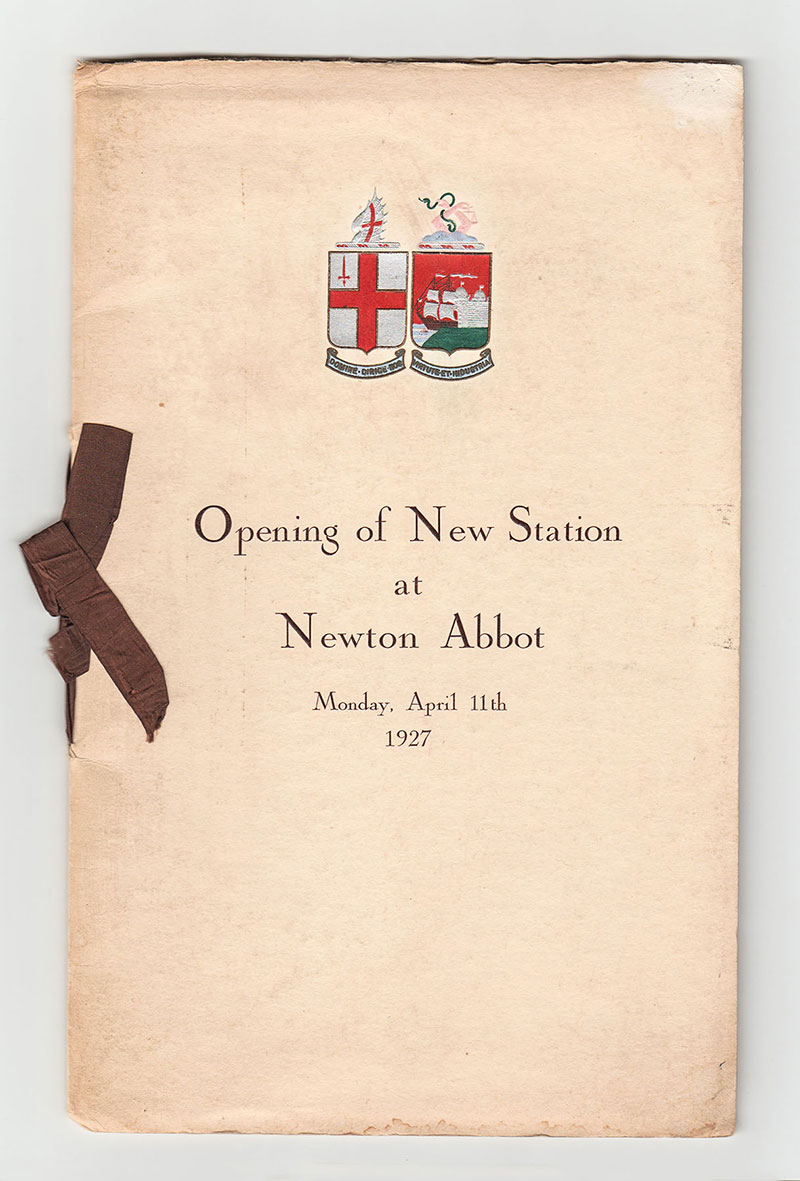

On Monday 11 April 1927, now 97 years ago, the Great Western Railway proudly held a very special ceremony to open ‘The New Station at Newton Abbot’ which is the title of the commemorative booklet they produced to mark that occasion, and on which we base today’s Blog.

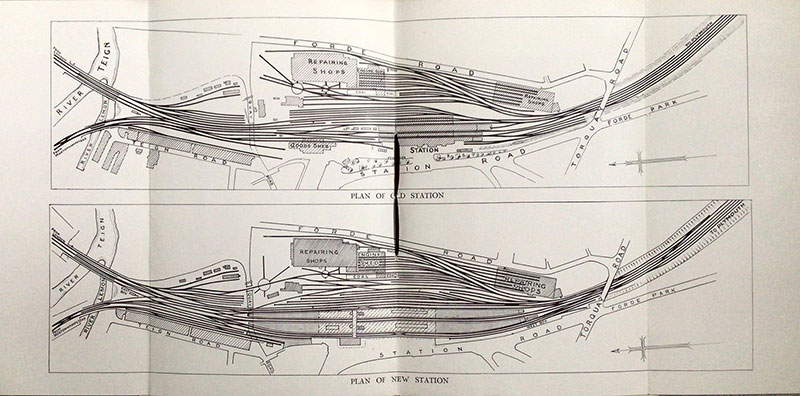

The 24 page booklet is part of the Great Western Trust collection, and is a remarkable survivor in such splendid condition. This may well be because the GWR spared no expense in having it produced in quality soft Yapp covers and brown cloth binding, within which are sepia images of the new and the old station and a fold out plan of the old and the new station plans including the nearby engine repair shops. We illustrate its cover and the station plans.

The GWR staff magazine published a full article on this event and the VIPs who took part. Typical of those times past, the event included toasts to the King, proposed by Lord Mildmay of Flete (GWR Director), The Town and Trade of Newton Abbot, again proposed by Lord Mildmay of Flete with the Response by Mr J Dolbear Chairman of the Urban District Council and The Great Western Railway, proposed by Mr F S Clark Chairman of the Chamber of Commerce and Responded by Viscount Churchill (GWR Chairman).

The Newton Abbot station plans, old and new

Of course having mentioned Toasts, the event could not pass without a celebration dinner, the menu of which is included in the booklet and quite appropriately the main course was Devonshire Spring Lamb followed by a dessert of Meringues and Devonshire Cream!

The very informative booklet described the original Brunel building and the plans to upgrade and replace it in 1914, but delayed by the war. A more modern design was then tabled and work began in November 1924. The local townspeople were so supportive of this massive undertaking that they donated to it the electric clock in the pediment surmounting the building, as well as the clock in the booking hall and the central controlling clock!

One of the preserved South Devon Railway wrought iron screens, originally above the entrance doors to the station. Photograph Geoff Sheppard by Creative Commons

The upper storey contained the HQ offices of the South Devon Divisional Locomotive Superintendent. Conscious of their historic importance, the GWR had preserved the original SDR (South Devon Railway) wrought-iron scrolls which once adorned the old station entrances, giving one to the Newton Abbot Museum, another incorporated within the building over the ticket window in the Booking Hall and the third, placed with the GWR’s own historic relics, then at Paddington.

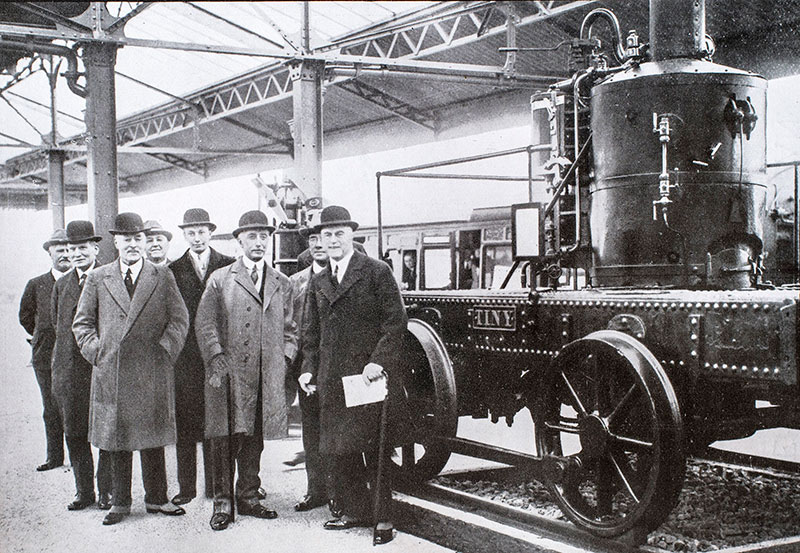

Of course, the other significant matter was the preservation on the platform of the Broad Gauge engine Tiny which itself is duly recorded in the booklet.

The South Devon Railway station building dating from 1848, photographed on 31 October 1923

Historically the town was once simply ‘Newton’ but with the spread of the UK railway network, that name duplicated other Newton stations, and the South Devon Railway had to add ‘Abbot’, and the town itself changed too, to Newton Abbot Urban District Council! Another example of the social impact of the railways upon our country!

Inside the original South Devon Railway train shed, photographed on 15 January 1925

The Great Western Railway Magazine included this report of the station reconstruction in its April 1927 edition:

Visitors this summer to the many charming South Devon seaside and moorland resorts which are reached through Newton Abbot will be impressed by the extensive improvements that have been carried out at that important station. The work, which was commenced in November, 1924, is nearing completion, and it is anticipated that the new premises will be formally opened for public use in the course of the current month.

The new station under construction on 14 October 1926, including the footbridge. The wooden structure on the opposite platform is a temporary refreshment room and gentlemen’s lavatory

The old station, which has been demolished, was one of the few remaining structures of the South Devon Railway Company, and except for minor improvements, had remained practically unaltered since it was built in 1846 from the plans, and under the supervision, of Brunel.

An imposing, three-storey block of buildings has been erected on the main Newton Abbot to Torquay road, facing the town park. The structure is of Portland stone and red Somerset bricks. A conspicuous feature of a pleasing façade is a handsome clock, placed in the centre pediment, which is the gift of the townspeople of Newton Abbot. Further evidence of the local appreciation of the work which has been undertaken by the Company is supplied by the Town Council having allowed some of their property to be encroached upon for the purpose of giving an excellent open frontage and spacious road access to the new station.

The station entrance building under construction on 14 October 1926

The three small platforms which formerly served the station have been replaced by two wide island platforms, each having a length of 1,375 ft., of which 570 ft. is veranda-covered. A separate bay platform of 320 ft. has been provided to meet the increasing traffic over the Moretonhampstead branch, which serves the eastern fringe of Dartmoor, a favourite summer resort. This will facilitate a quick and regular service of trains to the stations served by the branch.

This group with Tiny includes Viscount Churchill (Chairman), Sir S Ernest Palmer (Deputy Chairman), Lord Mildmay of Flete (Director), Mr H L Younger (Director), Sir Felix Pole (General Manager), Mr J C Lloyd (Chief Engineer) and Mr E Ford (Chief Goods Manager). Photograph published in Great Western Railway Magazine, May 1927

Important line alterations, when completed, will considerably increase the accommodation for dealing with trains, as there will be six lines through the station, with scissors crossings to give maximum freedom of movement. These are through, main, and relief lines, in each direction. Four lines, arranged on the parallel system, have been provided as far as Aller Junction. Two new manual signal boxes have been constructed at the east and west ends of the station, in place of the three previously existing, and it is of interest to note that one of them contains 206 levers, and is therefore the second largest manual box on the system.

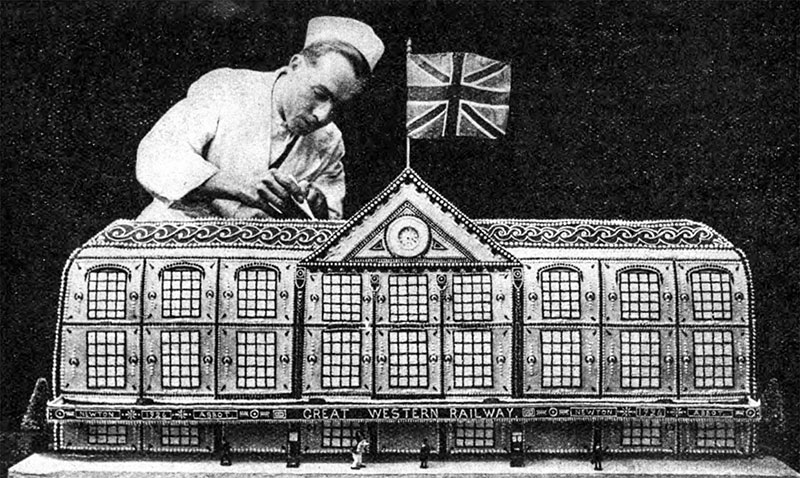

As a measure of civic pride in the new railway station, a Newton Abbot confectioner, Harold Phillips, modelled a gigantic cake, weighing several hundredweight, on the station building under construction. It took six men to carry the cake from the bakehouse to the shop window where it was exhibited for a weight-guessing competition during the 1926 Christmas season. Photograph published in Great Western Railway Magazine, January 1927

The accommodation provided for passengers is fully abreast of modern requirements. At street level there are booking and parcels offices, a spacious booking hall, and cloak room. Commodious refreshment rooms are available on each platform, also centrally-placed waiting rooms, and attractive bookstalls. The station is lighted by electricity, and all the buildings are centrally heated. On the first floor is a dining and tea room, 66 ft. by 19 ft. This room will be available for social functions, and has a separate entrance with staircase, which gives direct access to and from the street. There is a new telegraph office, and improved accommodation has been provided for the station master, inspectors, and other staff.

Newton Abbot railway station, photographed on 2 July 1965

The Company consider they have fully met the needs of Newton Abbot, and it is gratifying to know that the extensive work that has been done is thoroughly appreciated by the townspeople. There is small room for doubt, moreover, that visitors to the West Country, to the number of three-quarters of a million, who use the station each year, will be equally appreciative of the handsome manner in which their needs and comforts have been provided for.

TUESDAY 2 APRIL

Axle Box Syphon

Some heavy metal this week as we look at a syphon used for extracting water from locomotive axle boxes, shown here against the bogie of King class No. 6023. Water ingress would have been a problem in steam days and it was a critical task to ensure that the bearing had sufficient uncontaminated oil to prevent it running hot during a journey of perhaps two hundred miles or more.

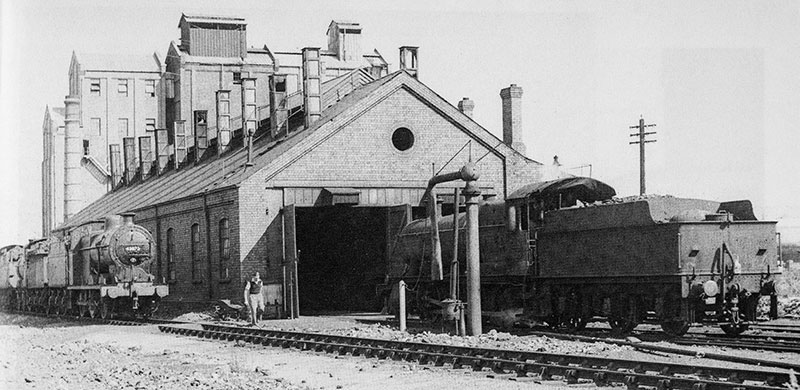

Stratford-upon-Avon engine shed photographed on 8 September 1957 by A R Gault. The shed had been built in 1910 and closed in September 1962

Some twenty four inches long and made of brass this item is beautifully finished, the two end caps and the handle being machined to improve grip whilst undertaking what was inevitably a slippery job. What makes this piece particularly interesting is that it has provenance. A brass plate stamped with the legend STRATFORD_ON_AVON. LOCO G.W.R. has been carefully rolled and soldered to the body of the syphon in case somebody tried to ‘borrow’ it. The photos of Stratford-upon-Avon engine shed show where the syphon would have been used.

Stratford-upon-Avon engine shed photographed on 27 August 1961 by Mike Hale. The shed was brick built, and the coal stage on right had a steel frame clad in wood

Even mundane, everyday objects have a story to tell and add as much to the Great Western Trust collection as more eye-catching items such as china, glass and silverware.

TUESDAY 26 MARCH

Children’s Education through Railway Publications

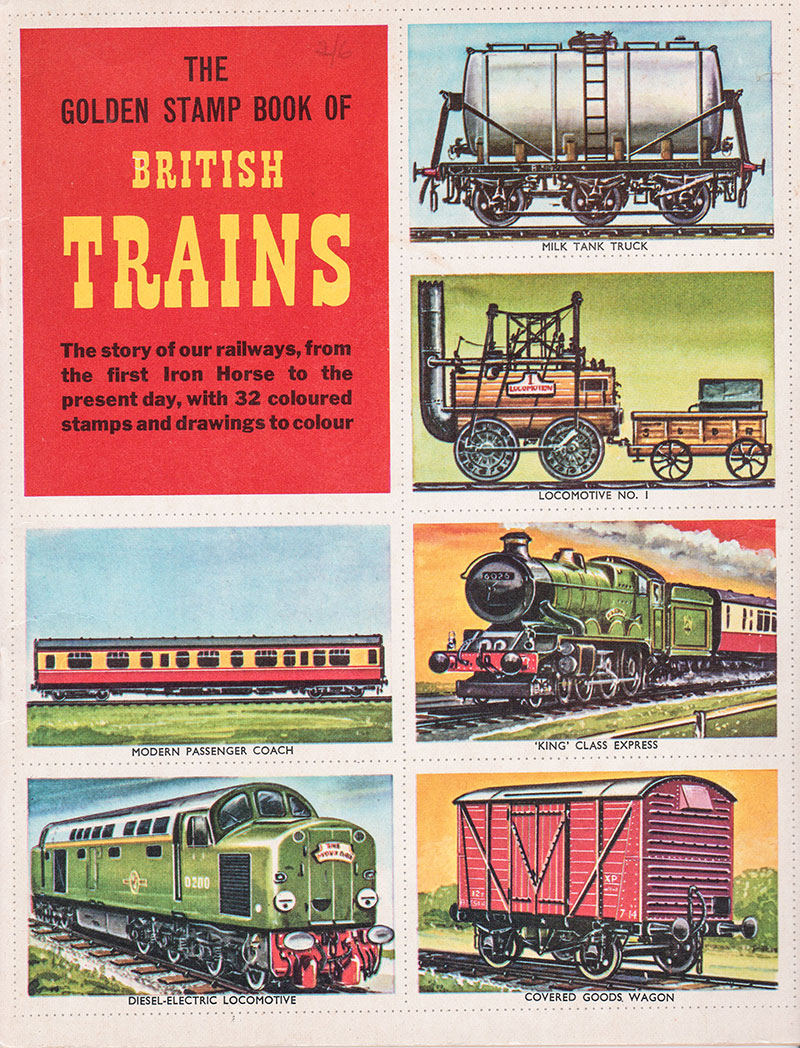

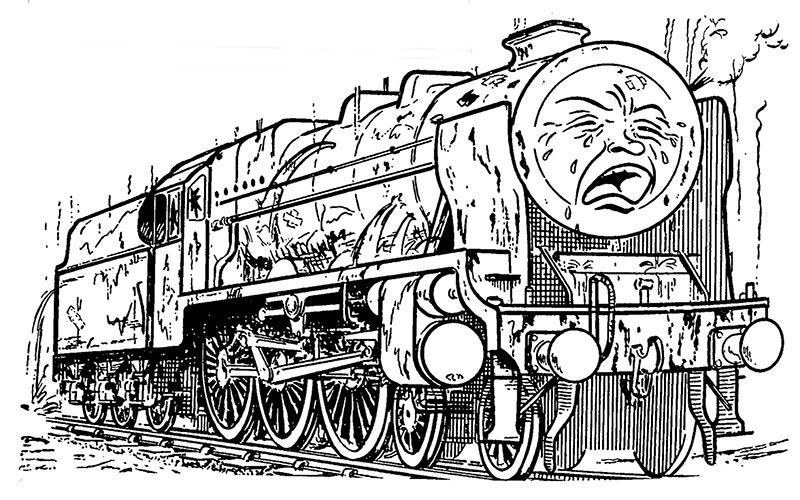

In four previous blogs on this subject we have recorded how the Great Western Railway produced children’s books and games that supported their image and gave varying degrees of educational content. The Great Western Trust collection, also holds a wide variety of that material of the British Railways era, both railway produced and that of a contemporary publisher. Our Blog today focuses upon ‘The Golden Stamp Book of British Trains’ published in 1961 by Purnell, who in fact published the Boy’s Own Annual in 1968 that we featured in our previous Blog on this topic.

As the cover illustration shows, it was quite a comprehensive publication providing a clever and engaging mixture of outline history of all railway related developments, drawings with some to be coloured in and ‘stamps’ (images of a variety of railway subjects) that were to be cut out and stuck in appropriate locations supporting the text. It even includes a weeping Royal Scot class steam locomotive lamenting that the steam age was ending!

Our example has been unused and whilst rather sad that a youngster hasn’t possessed and enjoyed it, it is for a museum collection a good example of the contemporary publications that publishers deemed worthy of investing in and of a quite different nature to that upon which Ian Allan first published for railway enthusiasts and train spotters.

We do not know how popular this particular publication was, nor its purchase price, but it now forms part of the Trust’s extensive collection of what we describe as our ‘Juvenile Railway Publications’ collection, that complements our model railway related items to record the wider story of how railways were then, though perhaps less so today, an important subject of interest to the younger generation.

Visiting Didcot Railway Centre today, is for many youngsters, their first engagement with railways and of course steam engines. Countless thousands have done so since we opened our museum, and we have wonderful examples of how that first visit has fostered a life-long interest in railways and many became our volunteers who now engage with each new generation to inspire them in just the same manner!

The weeping Royal Scot is on a page titled: ‘Why no more steam locos?’ and explains:

Evening Star is the last steam locomotive to be built for use on our railways. Why? There are lots of reasons. Here are some of them: A steam locomotive, though it is very powerful, is very wasteful and rather dirty. A great deal of the coal burned is wasted because its heat goes to making the metal parts of the engine hot instead of boiling water and making steam, which is what we want. Coal burned on a hot fire leaves what is called clinker, or bits of slatey stuff. This has to be removed regularly, and to do that you have to let the fire out, which means the engine cannot be used. Water boiled very hard leaves scale (you can see some of this, I expect, in your kettle at home) and this means that the boiler has to be cleaned out regularly, and again the engine cannot be used while this being done. A steam locomotive, in fact, works for about eight hours a day or less.

An electric engine or a diesel-electric engine, can work for much longer without attention. A big steam locomotive, with tender, can be run only one way – chimney first. An electric or diesel-electric engine can be driven from either end, so it doesn’t need to be turned on a turn-table at the end of each journey. Those are some of the reasons why we are saying good-bye to our old friend, the puffer.

TUESDAY 19 MARCH

Accidents Did Happen – No. 6

Our previous article in this series related to Didcot itself in the era of the BRWR horse Provender Building. Today’s Blog is both local to Didcot and remarkably appropriate given the locomotive that is central to the incident.

From our Great Western Trust collection, we illustrate an official BRWR Chief Mechanical & Electrical Engineer’s Department, Swindon, landscape format document ‘Re-Railing Instructions Class 52 Diesel Hydraulic Locomotives’ printed in January 1973. Of course the Class 52 designation, relates to the D1000 series ‘Western’ class locomotives introduced into service with class leader Western Enterprise in 1961, and all withdrawn by 1977.

The cover of the Class 52 Re-Railing Instructions booklet in the Great Western Trust collection

In the extended pre-diesel era, many photographs and accident records exist showing steam locomotive derailments and their recovery activities. Large running sheds had recovery vehicles, including steam cranes and very experienced teams of men, on call to quickly respond to any such event, major or minor. It would appear that that experience was like so many aspects of footplate training, learned ‘on the job’ the hard way, as little if any documentation like that illustrated for the diesel-hydraulic appears to have been produced.

Clearly these diesels were a different and rather more complex mechanical machine if derailed, and bad recovery action, could cause far more damage than the derailment itself.

That said, like so many instructions issued in booklet form on the railways, they were largely produced and regularly updated in response to events or rather better ‘experiences good and bad’, so that best practice could be shared with all staff who needed it. Hence this rather late, January 1973 issue when D1000 was first commissioned in 1961.

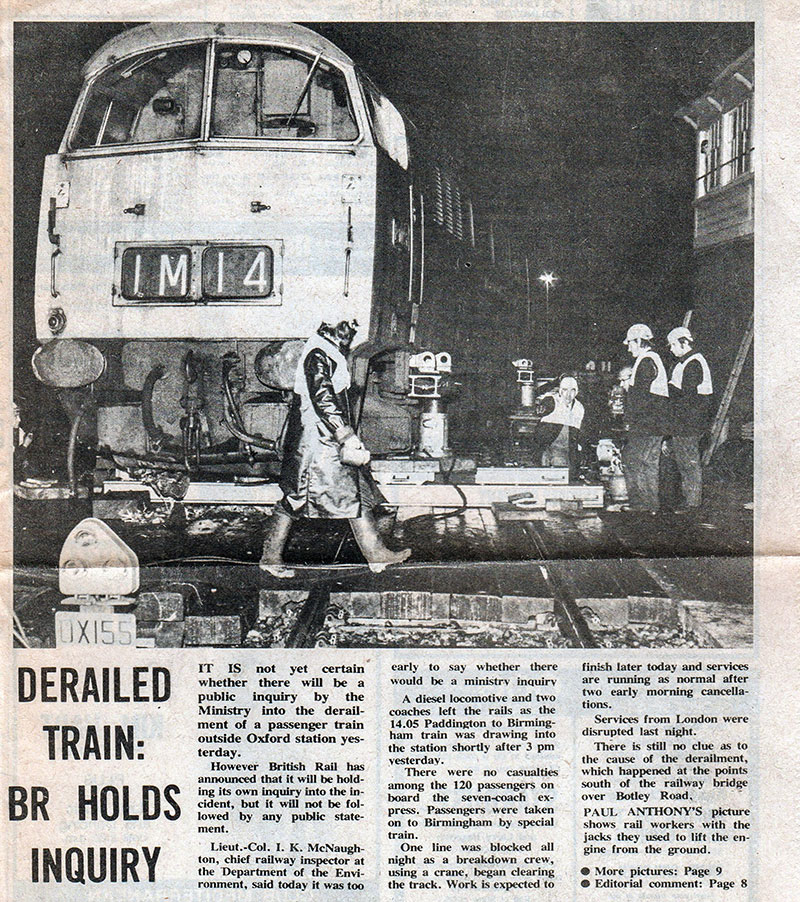

The Oxford Mail report of the derailment on 29 January 1975

The relevance of all this comes with an actual derailment to a D1000-headed passenger train when arriving at Oxford from Paddington on 29 January 1975. We illustrate an extract from the Oxford Mail of Thursday 30 January which clearly illustrates that the recovery crew are indeed applying the modern hydraulic jacks and steelwork to raise the front bogie up and clear from the track and traverse it to return it to the rails, ready for very gentle recovery away from the severely damaged track itself.

The derailment had been caused by fracture of the leading axle on the leading bogie as the train approached Oxford at 20mph. Fortunately it was not travelling at higher speed. The inspecting officer’s report of the accident can be read on the Railways Archive website at: https://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/documents/DoE_Oxford1975.pdf

D1023 being re-wheeled at Swindon Works

What is a remarkable coincidence of fate is that the derailed locomotive was none other than D1023 Western Fusilier, which was clearly repaired sufficiently to live on, and on 26 February 1977 headed the Western Tribute railtour in company with classmate D1013 Western Ranger. This was BR’s very final Class 52 railtour and D1023 was then selected to become part of the National Railway Museum’s collection.

D1023 on arrival at Didcot for her five-year stay, on 20 January 2023

Even more appropriate to our blog, is that she is now at Didcot Railway Centre on loan from the National Railway Museum for five years! She can be viewed, albeit in static display condition only, in our Locomotive Works.

TUESDAY 12 MARCH

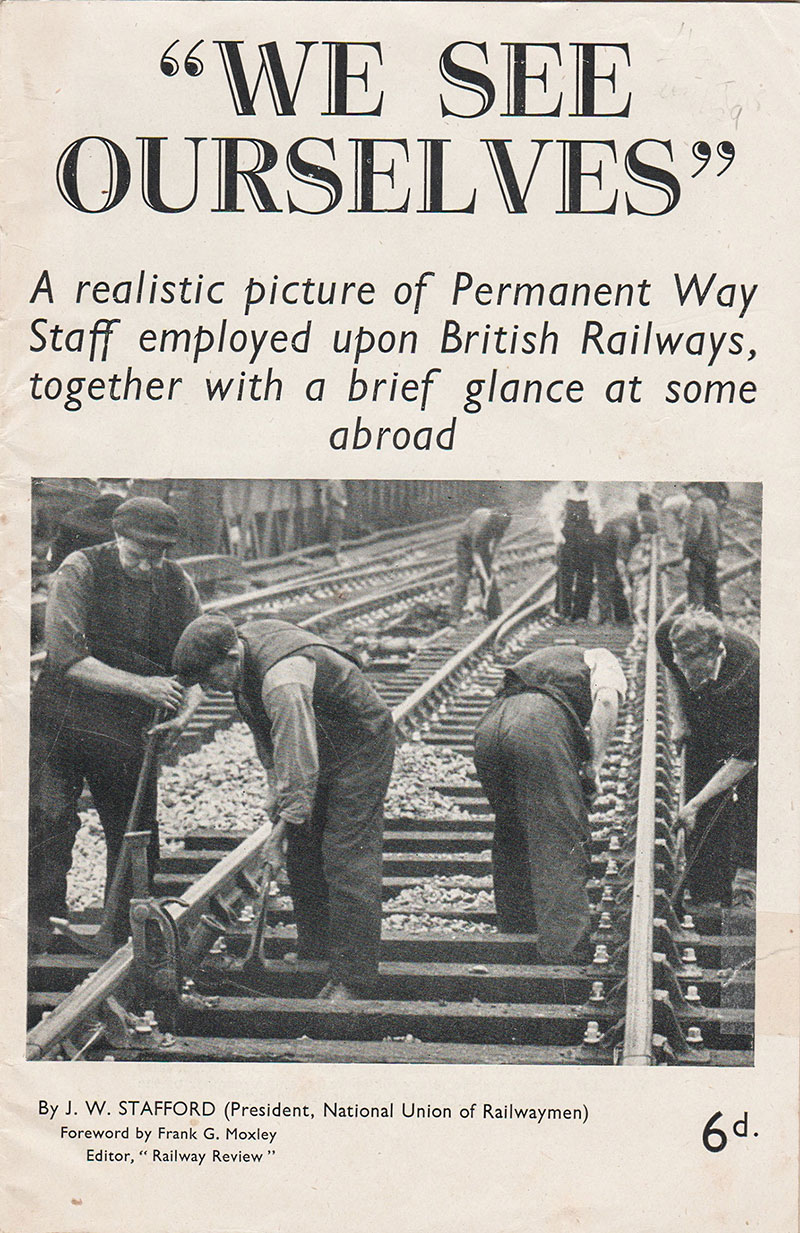

We See Ourselves – The Permanent Way Men

It is no accident that the founding Trustee and first Curator of the Great Western Trust, the late Fred Gray, directed that the very first display in our modestly sized Museum building at Didcot Railway Centre must be devoted to the Permanent Way, ie track etc. That display is largely still there after 42 years, and still fully justified. Why? Well as Fred would phrase it, without sound track and civil engineering, the trains would simply be useless!

Today we illustrate a truly remarkable booklet, published for six old pence in the BR era, by J W Stafford, the President of the NUR with the evocative title ‘We See Ourselves’. J W Stafford was a lengthman on the Great Western Railway, and later British Railways, for 33 years before he was elected president of the NUR in 1954. He asserted that it was management’s view in the 1930s that the heavier the tool, the greater would be the output of work, and that this belief had not entirely died out in the 1950s.

The foreword by Frank Mosley has a very telling opening comment which we quote: “Credit for building a cathedral is seldom given to the men who carefully and skilfully laid the stones. It is the same with a railway – in building it and keeping it in good order.”

This booklet itself is a comprehensive and very honest reflection of all aspects of Permanent Way staff employment, its challenges and its future prospects. Extending to no less than 21 sections on 23 pages, it includes ‘As Others see us’; ‘We were the Pioneers’; ‘Our Girls’; ‘A Dangerous Occupation’; ‘The Whitewash Train’ to ‘Airing our Grievances’ it is truly remarkable in such extensive coverage.

Yes, ‘We were the pioneers’ has a ring of factual truth given that both Stephenson and Brunel and many others, grappled with track form and design. Do not overlook that whatever is said in hindsight about Brunel’s adoption of the Broad Gauge, his singular use of ‘Bridge Rail’ has been proven to have provided, in its contemporary Victorian period, the greatest structural and dynamic strength per unit length than any other profile.

‘Our Girls’ is a frank reflection that wartime shortages of men caused females to be employed on this work. Stafford’s views, are not sexist, rather that given the arduous and dangerous nature of normal activities, it simply wasn’t a suitable environment. ‘A Dangerous Occupation’ needs hardly describing, and that cover picture will make the current Network Rail H&S staff shudder! Not a dayglow vest in sight!

‘The Whitewash Train’ may be a new factor to some blog readers, but the GWR and BRWR had such a special carriage, by which on ‘rough track’ the oscillation would prompt it to drop a large splash of whitewash on the track, for it to be discovered later by the ganger for that section, who had to take immediate corrective action! The carriage was introduced in 1931, converted from a 1911-built vehicle and remained in use until the 1980s, then known as the Track Testing Car.

The apprehension felt by members of a gang at the approach of this mechanical aid to good track maintenance was expressed in verse by J W Stafford*:

The whitewash train! The whitewash train!

Is running down our way again,

And woe betide if joints are slack,

Mayhap we all will get the sack,

Our nerves are simply on the rack,

We chant a sad refrain.

The whitewash train! The whitewash train!

We all have got it on our brain.

Inspectors warn us, “Be prepared”,

The ganger he is badly scared,

Small wonder that he bawled and blared,

And shouted yet again.

This photograph of the Track Testing Coach in use at Gloucester in the 1980s is by Phil Trotter – for more of his photos of rolling stock selected for their history, location or unusual features see: http://www.philt.org.uk/Misc/Rolling-Stock/

So, dear readers, as your train speeds you along, and maybe you are head down transfixed by a laptop or smart phone, just pause to thank those who in all hours and weather conditions, work on the track and formation and bridges, so that your train can apparently glide along without concern!

* J W Stafford’s verse is quoted in ‘The Railwaymen: volume 2: The Beeching Era and After. The History of the National Union of Railwaymen’ by Philip S Bagwell, 2022

TUESDAY 5 MARCH

A Very Special Locomotive

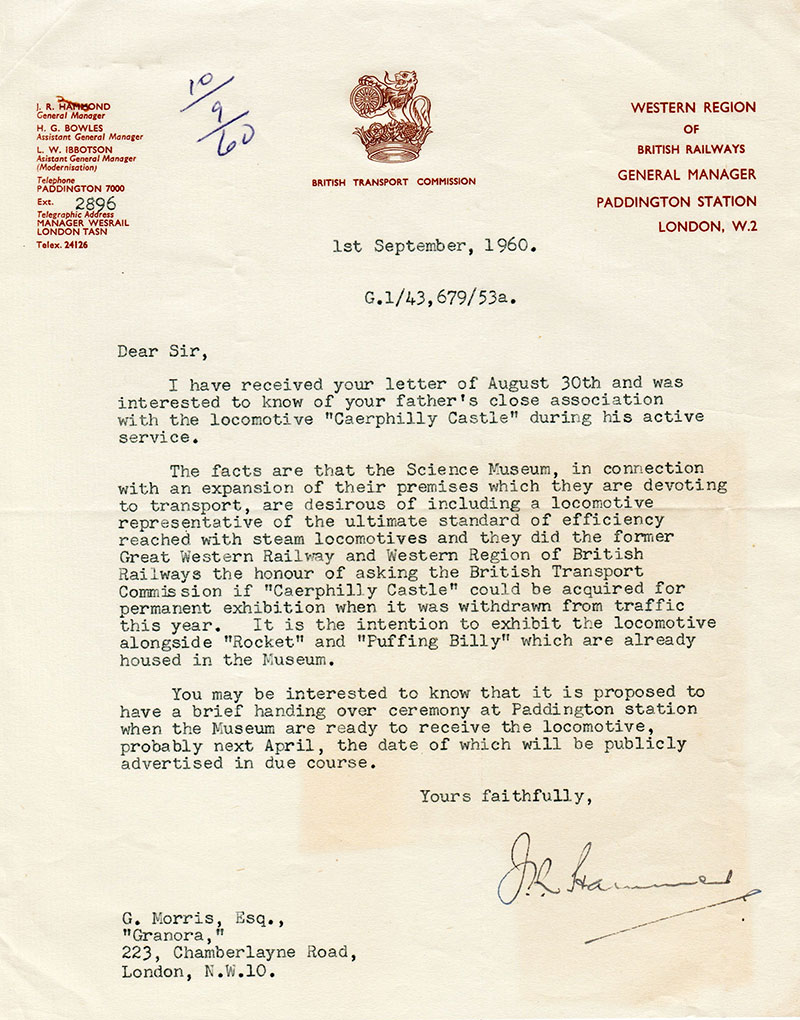

Most of our Blog readers should know by now that the Great Western Society has been joyfully celebrating the 100th birthday of No 4079 Pendennis Castle at Didcot Railway Centre. After her very long and celebrated working life, and then in preservation travelling around the globe to Australia and thankfully back to the UK for her permanent home with us, we thought it timely for the Great Western Trust to prove from our paperwork collection, that all this hullabaloo is not just the fancy of GWR steam locomotive enthusiasts but has the very best of justifications.

The letter which proves that the Castle class was selected by the Science Museum for representing the ‘ultimate standard of efficiency reached with steam locomotives’

In 1923 the class leader No 4073 Caerphilly Castle was built as the first of the batch of such locomotives, of which No 4079 followed in 1924. It is probably just an accepted historical fact that the then Science Museum in 1960 chose No 4073 for its new Land Transport Gallery in the Museum, and as we know, after many years there she now forms the centrepiece of the display at Steam Museum at Swindon.

4073 when new with driver William Morris

Well, through a remarkable consequence of events and individuals, the Trust has a unique document that provides the official justification for the Science Museum’s decision.

But first that background story. Quite remarkably, when first brought into service the Old Oak Common driver chosen to collect her from Swindon and bring her to Paddington for Directors’ inspection was William Morris. He then went on to drive her on the Great Western Railway’s crack expresses until his retirement. His son, Granville, was hardly one to forget such exploits and stories no doubt, and had memorabilia of his father’s career. So when he heard that 4073 was to be preserved, he wrote to the then BRWR General Manager, to inform him of his father’s exploits and enquire about the handing-over ceremony, to take place also at Paddington.

4073 on display at Paddington station in 1923

Thankfully, all those documents the Trust now holds, including the remarkable letter from the General Manager, one J R Hammond dated 1 September 1960, which we illustrate in full.

4073 awaiting restoration at Swindon in 1961

The key passage in the text is one we quote below:

“…The facts are that the Science Museum in connection with an expansion of their premises which they are devoting to transport, are desirous of including a locomotive representative of the ultimate standard of efficiency reached with steam locomotives and they did the former Great Western Railway, and Western Region of British Railways the honour of asking the British Transport Commission if “Caerphilly Castle” could be acquired for permanent exhibition when it was withdrawn from traffic this year. It is the intention to exhibit the locomotive alongside “Rocket” and “Puffing Billy” which are already housed in the museum.”

4073 in Kensington High Street on the move to the Science Museum. Photograph by Mike Peart

So, there we have it, from the Science Museum itself, the proof of the outstanding role the Castle class locomotives achieved in UK steam locomotive development. And dare we say it, that though not a phrase used in those days, its “standard of efficiency” was derived by comparison to its peers, from its then astonishingly low fuel consumption for power it exerted. In today’s parlance, it was the “greenest” locomotive class around!

4073 in display in the Science Museum in 1967

So for those who still question their credentials, we hope this unique official document, lays to rest any such cause for doubt about GWR Castle class locomotives!

Let’s all celebrate as we should, ever grateful for the preservation movement and our GWS members and volunteers who have lovingly brought 4079 back to life!

4073 in display in the loco works at Didcot in the 1990s, during the time between leaving the Science Museum and the Steam Museum at Swindon being opened

TUESDAY 27 FEBRUARY

Barmouth

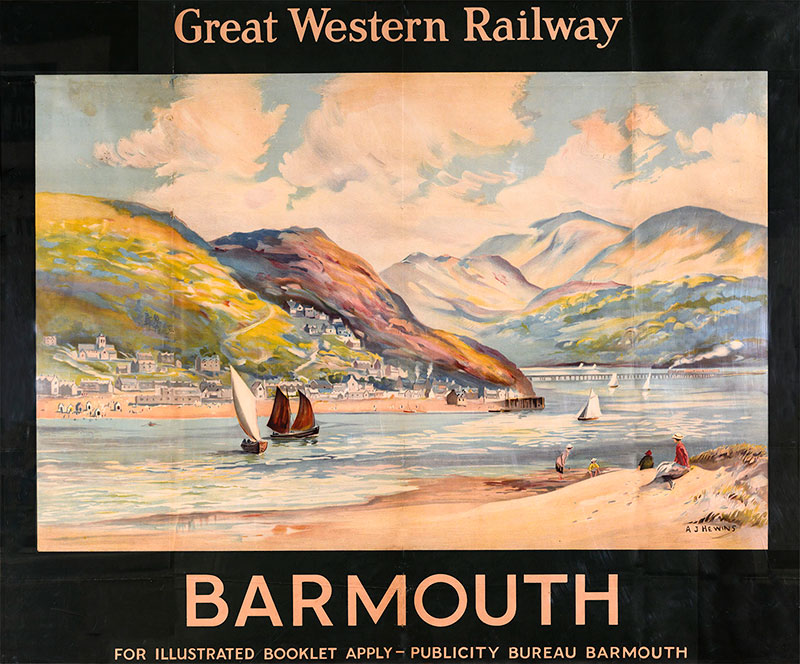

We travel to the Cambrian Mountains this week and the town of Barmouth. Situated on the shore of Cardigan Bay, it has long been a popular holiday destination ever since the opening of the railway in 1867. Its beautiful location on the mouth of the Afon Mawddach, Merionethshire (now part of Gwynedd) has made it a magnet for holidaymakers and before the advent of mass car ownership, the station saw regular through trains from London, the Midlands and the North West. Between Dovey Junction and Pwllheli passengers were and still are treated to some spectacular views of the Cambrian coast, crossing the Mawddach on the most significant civil engineering structure on the line, Barmouth Bridge.

The first poster dates from 1924 and is a stunning view with the artist, A J Hewins, using some licence in looking across to the town with the brooding mountains above and a down train crossing the bridge. Although published in the mid 1920s, the liberated society of the time had obviously not reached North Wales as bathing machines are still in evidence on the beach, there to protect the local citizens from the low morals of the big city visitors.

Our second poster was issued in 1962 and is in a very different style. Gone are the big skies and distant figures. Instead, the main attraction is a very shapely lady in traditional Welsh costume whose presence draws the viewer into to the town beyond. Exactly what the artist, Henry Stringer (1903-1993), would have wanted, although one cannot help wondering if he was also a fan of Sophia Loren and other Hollywood stars of the time.

Both of these posters form part of the Great Western Trust collection and others are on display in the Trust Museum at Didcot Railway Centre, home of the Great Western Society.

TUESDAY 20 FEBRUARY

A Special Consideration

Those familiar with the name Cecil J Allen will know of his very extensive locomotive running logs and observations on all the Big Four railway lines that were published over many years in The Railway Magazine. He could only obtain direct, footplate access on many trains, through a generous provision or rather special consideration, by the senior managers on those lines including the GWR. From our Great Western Trust collection we illustrate a modest commercial postcard image that most helpfully had a detailed longhand annotation on its reverse that proves this point.

The Cornish Riviera Limited on 17 October 1927 with Cecil J Allen on the footplate. Photograph by F E Mackay

It may often be said that there is no such thing as bad publicity, but of course in the case of a working railway, a contemporary and much published observer of footplate and locomotive performance under daily operations like C J Allen, brought the risk of him experiencing a bad day at the workplace! Hence, to keep an eye upon C J Allen, his interaction with the footplate crew, and represent the GWR Company officially, a senior loco inspector always accompanied him on such journeys.

The train in question is the down Cornish Riviera Limited express on 17 October 1927, just passing Kensal Green. Loco No 6005 King George II, is being driven by Driver W Rowse and Fireman J Osborne, with Chief Inspector Robinson overseeing activities. Cecil J Allen is leaning out from the cab, with distinctive hat, having pre-arranged with the photographer F E Mackay the location for this photo opportunity! With the introduction of the King class locomotives, the non-stop schedule from Paddington to Plymouth was reduced from 248 minutes to an even four hours.

Cecil J Allen was born in 1886 and died on 5 February 1973. He joined the Great Eastern Railway in 1903 and went on to become an inspector of materials for the LNER. He also had a prolific career as a writer, publishing many books on railway subjects. He authored the long-running monthly series British Locomotive Practice and Performance from 1909 to 1958 in The Railway Magazine.

He was a supporter of the Crusaders’ Union and organised three special trains in January 1929 to take members of the Union from Paddington to Swindon Works, as well as tours in subsequent years.

Cecil J Allen described his journey on the Cornish Riviera Limited Express in October 1927 in British Locomotive Practice and Performance published in The Railway Magazine’s December 1927 edition. A set of bound volumes of The Railway Magazine is also in the Great Western Trust collection. We reproduce the article below as it captures the atmosphere of a long non-stop journey on a powerful steam locomotive with a heavy train.

For those unfamiliar with steam engine terminology, the regulator is the valve which lets steam from the boiler to the cylinders, and the cut-off controls the valves which admit steam to the cylinders, and remove it afterwards to be exhausted out of the chimney. The lower the number, the more efficiently the engine is working, so a 15 per cent cut-off means steam is admitted to the cylinders for 15 per cent of the piston stroke and the steam expands to drive the piston for the remainder of the stroke. When the engine is slogging up a gradient more power is required from the cylinders, so a 35 per cent cut-off admits steam for more than a third of the piston stroke.

Slip coaches might also be a mystery to some. This is a practice of detaching a coach or coaches from the rear of a train while it is on the move. The main train carries on without stopping, while the detached vehicles coast to a halt in the station under control of a slip guard. The advantage for the Cornish Riviera Limited on its non-stop journey from Paddington to Plymouth was that the original 14 coaches at the start of the journey had reduced to seven after slips at Westbury, Taunton and Exeter, giving the engine an easier task in tackling the steep gradients between Newton Abbot and Plymouth.

Now let us sit back and enjoy Cecil J Allen’s description of the journey:

British Locomotive Practice and Performance, December 1927

It is not unnatural that the most urgent desire of many readers who make a close study of locomotive performance should be – judging by their letters – to know something of the achievements of the latest locomotive masterpiece from Swindon. On paper there has been little question as to the new King George V class being the most powerful express passenger locomotive in the country. The tractive force formula gives the engine an advantage even over the 4-6-2 Pacific Enterprise of the LNER with its enhanced working pressure of 220 lb sq in.

But the question of real interest was to see whether the King George V boiler could supply steam with sufficient rapidity to make the tractive force calculation effective, and in particular to ascertain if it would be possible to maintain the high working pressure of 250 lb continuously in maximum conditions of working.

By the courtesy of Mr C B Collett CBE, Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Great Western Railway, to whom this wonderful design owes its inception and its execution, I have been able to obtain, as an eye-witness, the answer to both questions. And let me say here, without delay, that it is a triumphant affirmative.

Six years ago I made my first down journey on the Cornish Riviera Limited express. Stars were the 4-6-0 engines then in the ascendant on the GWR, and it was with Lode Star that Driver Springthorpe gave me that remarkable journey described in the December issue of 1921, whereon we gained no less than 16 minutes on schedule between Westbury and Lipson Junction. Loads were much lighter in those days. Our 430 tons from Paddington dropped to 360 at Westbury, 295 at Taunton and 260 at Exeter.

No 4079 Pendennis Castle departing from Paddington station with the Cornish Riviera Limited, photograph by H W Peckham. Cecil J Allen rode from Paddington to Plymouth on the same train with this locomotive in October 1924 and compares performance of the Castle class with the new King class throughout this article

Then, in 1924 – exactly three years later – it was my privilege to ride down with Driver Young on Pendennis Castle, in a second trip specially memorable in that we succeeded with a train 100 tons heavier than that hauled by Lode Star, in passing Westbury 95 min 35 sec after leaving Paddington. This was detailed in December 1924.

And now, in December 1927, I have to describe my first journey on one of the new Kings, of the more comparative value in that the load behind King George II was almost identical with that carried behind Pendennis Castle three years before. But the King has the harder task, partly on account of that particular handicap which is impossible to reduce to figures – a strong head wind, which at times became a side wind – and partly because of the fuel, to which I will have occasion to refer later.

The three journeys were all made at about the middle of October, when the Limited is generally at its heaviest, after the post-summer restoration of the Taunton and Exeter slip portions. The last two journeys were made on Mondays, also, when extra load is usually carried, particularly on the Exeter slip.

It was encouraging, as I crossed the bridge from Bishop’s Road, to notice that the Falmouth coach was underneath it, which meant that both the St Ives and Penzance portions must be further still up No 1 platform; but a final examination of the train showed that my previous maximum of 14 vehicles had not been exceeded. However, this aggregate tare of 491 tons, with the train well filled in every part, gave promise of a gross load of fully 525 tons behind the engine tender.

From the rear end the formation of the train consisted of two 70 ft coaches for Weymouth, to be slipped at Westbury; a 70 ft for Minehead and a 60 ft for Ilfracombe, to be slipped at Taunton; a 70 ft and a 60 ft for Exeter and a 70 ft for Kingsbridge, to be slipped at Exeter; and then, in the main part of the train, 70 ft coaches for Newquay, Falmouth and St Ives, and a four-coach set, including restaurant car, for Penzance. I know of no other express in the country carrying in its formation as many as nine independent portions.

On reaching the engine, I found that I was travelling with Driver Rowse, Fireman Osborne and Chief Locomotive Inspector Robinson. In the commodious cabs with which these engines are fitted there was comfortable room for all of us. As regards weather, the day which had opened dull and cloudy, was beginning to improve, with the sun just breaking through, but rather a nasty wind getting up from the west.

The fuel – the other important point bearing on the journey – looked satisfactory to outward appearances; but it was to be discovered later that under the large lumps of coal which had been brought forward to the tender was a considerable quantity of slack that was little better than dust.

It was a shade after time when the signal was given to start, and at about 10.30½ Rowse opened the regulator, moderately at first, in order to avoid the possibility of slipping. Full forward gear was employed until we were well under way, but the cut-off was brought back until, no further from the start than West London Junction, King George II was cutting-off at 23 per cent of the stroke. By Hanwell this was down to 20 per cent, and by West Drayton we had actually got down to 17 per cent. Meanwhile, the regulator had been opened to nearly its full opening, which was the general position for all of the harder running, except for the fact that it showed a slight tendency to work backwards of itself from time to time, to a position which appeared, from the angle of the regulator handle on the quadrant plate, to be about three-quarters open.

From Hanwell to West Drayton we accelerated on the level from 55 to 60½ mph, on 20 per cent cut-off, and from there to Slough, with but 17 per cent cut-off, the engine worked this vast train up to a speed of 62½ mph. It was astonishing, on my previous trip with Pendennis Castle, to record a maximum of 69 miles an hour at the same point, with the engine cutting-off at 26 per cent of the stroke, but a speed of 62½ an hour with the same load of 525 tons, at no more than 17 per cent cut-off, seemed a perfectly amazing experience. I doubt, indeed, if it could be paralleled with a simple locomotive in any part of the world, apart from the use of valve motions of the Caprotti, Lentz or other special types. Of all the achievements of our engine throughout this four hours’ journey, no feat was to me more striking than this.

Immediately after Slough there came a permanent way check, which brought us down to 40 miles an hour, but for recovery from this it was not necessary to open out the engine to more than 22 per cent cut-off, and by Maidenhead we were down again to 20 per cent. But the acceleration here, once we had got above 50 miles an hour, was somewhat slow, although we had just contrived to attain the mile-a-minute rate at Sonning when steam was shut off for the Reading slack.

The silent working of the great engine, no less than the steadiness of her running, was most impressive; it seemed impossible on the footplate to realise the colossal output of energy, sufficient to move this gross weight of over 650 tons at an average rate of 60 miles an hour. Indeed the exhaust of the engine was completely inaudible, even on the footplate, at any cut-off below 20 per cent – that is to say for the major part of the journey – and not until 30 per cent, which was only reached at three different points, did it become really vigorous. But a backward view of the one-fifth-of-a-mile length of our train, winding round the curves from Reading to Southcote Junction, was enough to dispel any illusions as to the problem of haulage which lay both behind and before us.

To Reading we had dropped 3¼ min on schedule, of which the permanent way slack accounted for slightly over 1½ min, the remainder of the loss going against the engine. But we were to see later that there was method behind this apparently easy working.

After the Reading slack, Driver Rowse still left his cut-off at 20 per cent, and this all but brought us to the mile-a-minute rate before Aldermaston, where for the second time we were badly slacked for permanent way repairs. For recovery from the second check a cut-off of 21 per cent was employed for a short time, but this was brought back at Thatcham to 19 per cent, which sufficed to raise the speed to 57½ mph on the slight descent beyond Enborne Junction. It should be emphasised, however, that in general grading up the Kennet Valley is against the engine, with an average of 1 in 400 from Theale to Kintbury; and yet a cut-off position below 20 per cent was found enough for maintained speeds of over 55 mph. At Kintbury the grades steepen slightly, but it was not till Hungerford that the cut-off was advanced to 20 per cent, and then by 1 per cent at a time – on what other line than the Great Western could such artistic precision of driving method as this be seen? – we moved steadily up to a maximum of 24 per cent, just before topping Savernake Summit. Nothing more than 24 per cent to take a 525 ton express up 3 miles steepening from 1 in 175 to 1 in 106 – the culmination of a 30 mile rise – at a minimum rate of 49 miles an hour! It was a miracle. We had dropped 5 minutes to Bedwyn, but the majority of this loss could be debited to the two slacks; steady recovery of time was now the order of the day.

Once over Savernake Summit, Driver Rowse reduced the cut-off to 15 per cent, and substituted the small auxiliary port of the regulator for the main opening, and in this way we drifted smoothly down the Westbury, only missing the attainment of 80 miles an hour, below Lavington, by the narrow margin of a single mile. Relieved of the Westbury slip portion, and thus with a gross load of 450 tons, King George II now performed some remarkable work up the Brewham Summit, better known, perhaps, by its familiar title of “mile post 122¾”.

In recovering from both Westbury and Frome slacks, the 25 per cent cut-off position was employed, with the regulator a little short of fully open, but whereas Young (who was before time on my Pendennis Castle trip), had been content with between 22 and 23 per cent from beyond Frome up to Brewham, Rowse maintained his 25 per cent cut-off to the top. The difference in the two speeds was amazing; up the last mile at 1 in 107-112, Pendennis Castle fell to 39½ mph, whereas King George II with a cut-off but 2 per cent longer, carried the same load over the top at no less than 51 miles an hour!

We then travelled with the utmost gaiety over the easy length from Brewham to Cogload, cutting-off at 15 per cent, and with the auxiliary regulator port, as nearly as I could judge, fully open; speed slightly exceeded 80 mph below Bruton, was eased slightly past Castle Cary, and then reached 74 at three different points to Cogload. In this way we regained 3½ minutes between Westbury and Cogload Junction, and were now only 1½ minutes “down” in our total time from Paddington.

It was at this point that the fire began to give some concern to the crew. Pressure had been consistently maintained at round about 240 lb per square inch for most of the journey until now, but as we approached Taunton the needle was inclined to droop, so that we had not here more than 220 lb of steam. Throughout the journey it had been necessary for Fireman Osborne to make frequent recourse to the pricker, and his labours in firing had gradually assumed a more arduous form owing to the poor quality of the coal.

The ”attack” on Wellington bank had, therefore, to be made rather less strenuously than is normally the case, and on the new schedule of the train we lost 1½ minutes between Cogload and Exeter. Owing to the lower steam pressure, which fell to exactly 200 lb at the top of the bank, the cut-off positions had to be almost exactly the same as those of Pendennis Castle on my previous trip – 20 per cent at mile post 167¾, where the incline proper begins, gradually increased to 30 per cent past Wellington and 35 up the final mile. But the speed on the upper part of the bank was considerably higher, being 40½ mph at mile post 173 (at the mouth of Whiteball Tunnel; the summit of 2½ miles rising at 1 in 80-90) as against Pendennis Castle’s 31 mph. Even in adverse conditions, therefore, the superior power of King George II was abundantly apparent.

From Whiteball down to Exeter, we reverted to 15 per cent cut-off and the auxiliary regulator port, and the latter was not fully opened, in order that the steam supply might be husbanded to the greatest degree possible while the favourable grades permitted. The crew were thus rewarded by seeing the pressure gauge needle creep up to the “240” mark as we breasted Exeter.

We were thus 3 min down on the schedule allowance of 174½ min for the 173.7 miles from Paddington to this point, but by the release of the three vehicles forming the Exeter slip, our load had now shrunk to exactly one-half the fourteen coaches pulled out of Paddington, and such was the relief that Driver Rowse proceeded to regain the whole of the arrears on the next 20 miles to Newton Abbot.

Although in no more that 15 per cent cut-off, and with the regulator not more than one-half open, the engine regained speed with extraordinary rapidity along the level shores of the Exe, so that we dashed across Exminster troughs at fully 73 mph; after this followed the necessary easing round the curves past Starcross, Dawlish and Teignmouth, and a severe slack though the new station at Newton Abbot.

Now the formidable ascent of Dainton lay ahead, and directly we were past Newton the regulator handle was pushed hard over, and the cut-off advanced to 20 per cent. Up the final two miles, steepening from 1 in 57 to 1 in 41, and including a short strip at 1 in 36, cut-off changes were rapid, until finally we threaded the short tunnel, and passed Dainton Box – an operation which, from the footplate, looks like running over the gable end of a house – in 35 per cent cut-off. Pendennis Castle had gone over at 24½ mph in 42 per cent cut-off; we went over at 27½ mph in 35 per cent cut-off. Loads were identical, and in both cases the regulators were full open; such comparisons speak for themselves.

Down the incessantly winding descent to Totnes we went with great caution, and passed that station ½ min inside time. There now lay ahead Rattery bank; the first 2½ miles to Tigley Box steepening from just under 1 in 70 to 1½ miles continuously at 1 in 46-57; then 1¾ miles, mostly at 1 in 90 to Rattery Box; and a rather easier mile to the 228½ mile post, whence there are moderately rising grades to Wrangaton.

With regulator full open, Rowse advanced his cut-off gradually to 35 per cent, on the steepest part of the bank, and maintained it there up the 1 in 90 from Tigley to Rattery, whereby we accelerated from 28½ to 43½ mph up 1¾ miles of this grade. Pendennis Castle, at 33 per cent, merely gained the difference between 27 and 33 mph. Then our cut-off was dropped to 25 per cent at Rattery, further to 20 just beyond Rattery Tunnel – although this did not prevent us from attaining 60 mph up the rising grades past Brent – and 15 per cent at Wrangaton, where the auxiliary port once again replaced the main regulator opening.

All our troubles were now over. We had lost a minute between Totnes and Brent – the working times optimistically require an average rate of 45 mph up this ascent! – but we were on the right side of time at Hemerdon. Down the famous descent of Hemerdon with closed regulator and frequent brake applications; cautiously round the curves from Tavistock Junction to Lipson Junction; 23 per cent and an open regulator up the last stretch to Mutley; and we rolled proudly under the roof at North Road and came to a dead stand at 2.28·20 pm, 237 min 50 sec after leaving Paddington, and nearly 1¾ min early.

Little remains to be said about the run. When we got down to Laira Shed, the engine proved to be perfectly cool in every bearing, and apparently quite fit for an immediate return to London. Not so the crew and “passengers”, however. I should not like to say how long I spent in scraping off my superabundant coating of grime; the four of us certainly bore no uncertain evidences of the character of the coal which had been burned. But for all that, I would not have missed the experience; it was an education.

Had I been a passenger in the train, I should have wondered at the comparative moderation of the descent from Whiteball to Exeter, when the train was behind time; on the footplate the reason, of course, was obvious. But the coal, the wind, the slacks and the accelerated schedule combined, between them, further to enhance the merit of a wonderful journey; and it is on occasion such as these, when difficulties have to be surmounted, that one realises the wealth of experience and scientific skill that is bound up with successful driving and firing. My warmest appreciation, ere we parted, was expressed to Driver Rowse and Fireman Osborne; I hope that I may have some more

TUESDAY 13 FEBRUARY

British Industries Fair 1934

The Great Exhibition of 1851 began a trend for such nationally focused events that lasted at least until the Festival of Britain in 1951. Perhaps less well known are the more specialised exhibitions that had one subject at their focus. One such that we illustrate today from the Great Western Trust collection was the British Industries Fair of 19 February to 2 March 1934, held 90 years ago in London and Birmingham.

The two locations reflected their then established role as major centres of commerce and railway communication. London for its industries, now largely office or “Technology Park” focused but once having quite heavy industry in the suburbs, and Birmingham, well established as the manufacturing centre for countless industries.

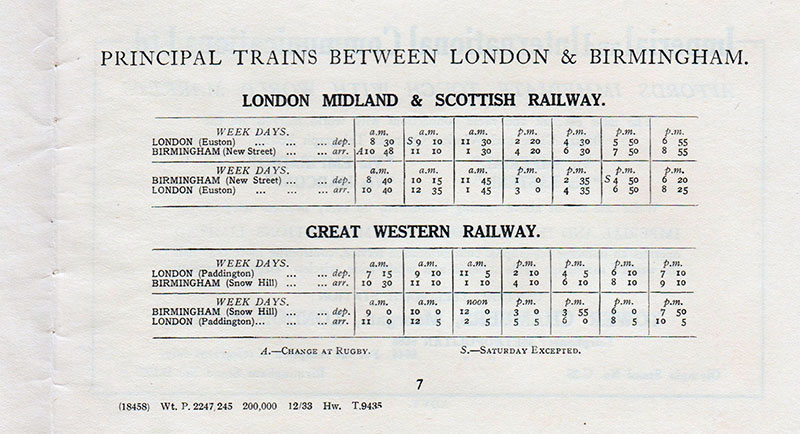

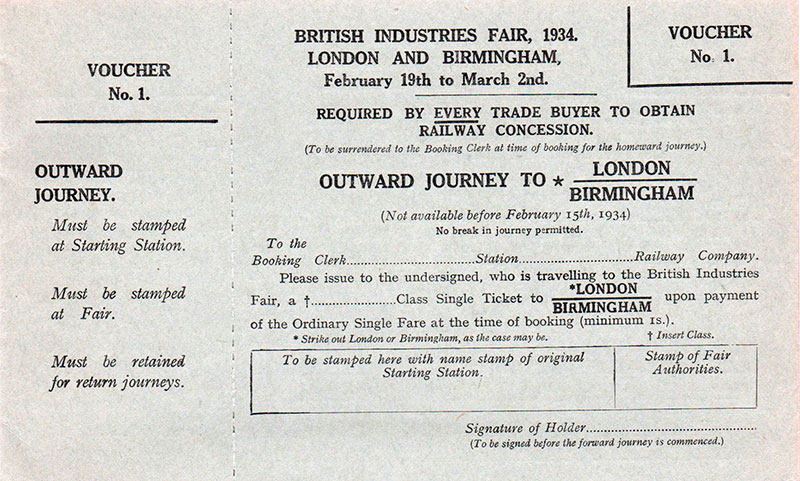

The items illustrated are unused and complete, special vouchers for reduced fares to this exhibition, printed and issued jointly by the Great Western Railway Co and the London Midland & Scottish Railway Co, as a shared venture, acknowledging that both companies had direct train routes from London to Birmingham. So we have the cover of the enclosing folder for the multiple parts, its inclusive timetables of trains on both systems and the Voucher No 1 images.

From the very small print on the timetable illustration, it shows a remarkable run of 200,000 in preparation dated December 1933! Yes, these events drew massive attendance, but quite how many vouchers such as these were actually used on either railway route, is sadly unknown.

The photographs of station decorations at Paddington in 1950 and Birmingham Snow Hill in 1951 show the efforts made by the railways to add a sense of occasion for travellers to the Fair.

A short history of the Fair

This history of the Fair is published on the National Archives website:

“The first British Industries Fair (BIF) was held in 1915 at the Royal Agricultural Hall, London, in an attempt to encourage British firms to produce goods which had traditionally been imported from Germany and other countries. Only the exhibition of British goods was permitted and a total of nearly 34,000 attended. The success of the first Fair led to further Fairs being held in 1916 and 1917 at the Victoria & Albert Museum, and in 1918 and 1919 at the London Docks.

“A section of the British Industries Fair was organised in Glasgow in 1917, 1918, 1920 and 1921.

Station decorations at Paddington during the 1950 Fair, held from 8 – 19 May that year

“Another section representing the heavy industries was inaugurated at Castle Bromwich in Birmingham in 1920 with the aid of a grant for publicity from the Board of Trade. These two sections accompanied the London section which was held at Crystal Palace from 1920. In 1921, a Board of Trade Committee of Inquiry under the chairmanship of Sir Frank Warner recommended that the Glasgow section be discontinued and the Fair be maintained on an annual basis with one section in London and another in Birmingham. The Fair was held each year until 1957 except in 1925, the second year of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, and 1941 to 1946.

“The London section was held at White City from 1921, and in 1930 a second section was added and this was held at Olympia. From 1938 the two London sections were held at Olympia and the newly opened Earls Court building. The Birmingham section remained at Castle Bromwich.

Station decorations at Birmingham Snow Hill during the 1951 Fair held from 30 April – 11 May that year

“By 1948 the purpose of the BIF was described by M Logan in The Histories of the Fair as being: ‘to show the world the strength of British industry, the craftmanship, the design and the quality that is implied in the words “British Made”.’

“Originally the responsibility for organising the London section of the Fair lay with the Board of Trade but it was transferred to the Department of Overseas Trade on 1 April 1919 who, together with the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce, were also responsible for the Birmingham Fair. It returned to the Export Promotion Department of the board in 1946, and was exercised by the new Commercial Relations and Exports Department of the board after 1 January 1949. After the 1954 Fair responsibility for organisation and management was transferred to a private company, British Industries Fair Ltd. The Company was voluntarily wound up on 20 February 1958 and the Fair has not been held since 1957.”

TUESDAY 6 FEBRUARY

Flights of Fancy

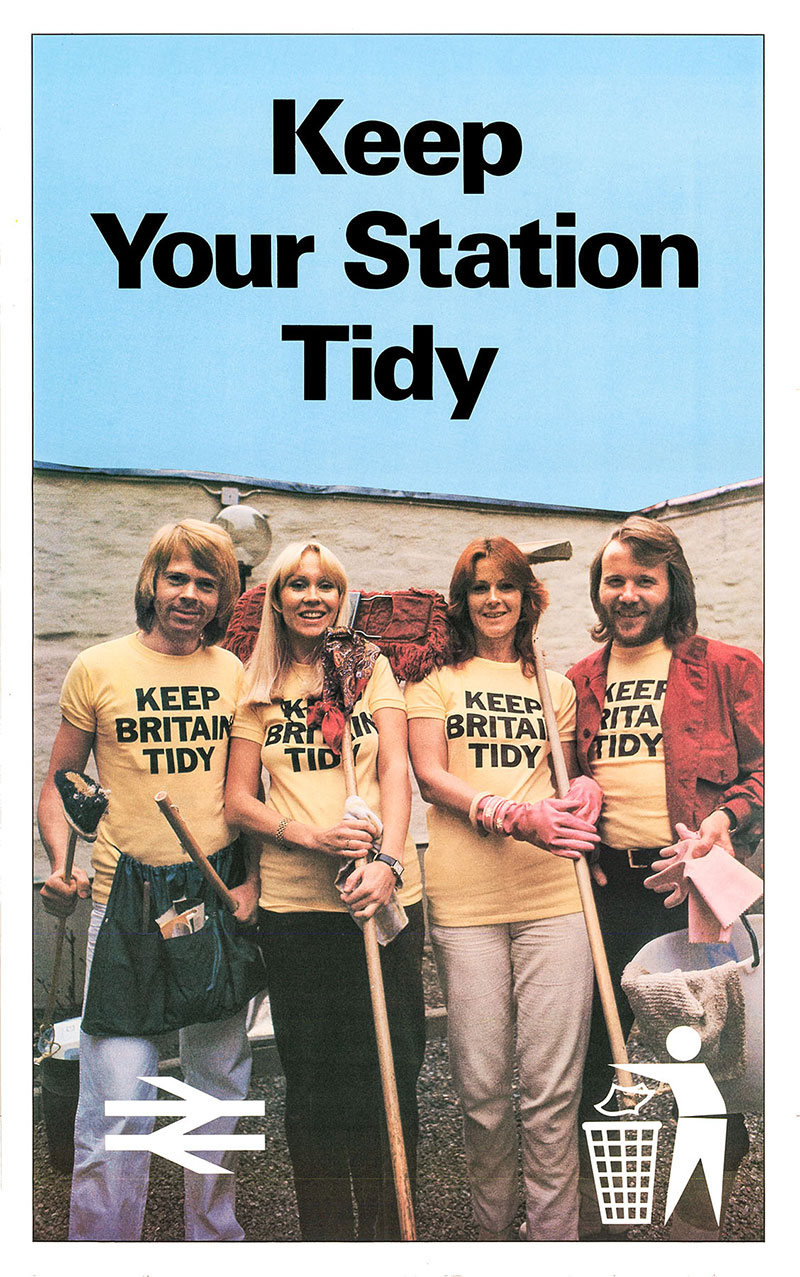

Two rather unusual posters from the Great Western Trust collection call for our attention this week. Neither of them features a railway scene even though they would have been posted at major railway stations. They are also both relatively modern although fifty years ago is ancient history in the world of advertising.

First we have Sweden’s most famous export – ABBA. Quite how their agent at the time persuaded them to pose with mops and buckets is a mystery but the old saying ‘no publicity is bad publicity’ certainly works in this instance. The band was formed in 1972 and found global fame two years later after winning the Eurovision Song Contest and the poster shown here was part of the image building process that followed. Despite not having worked together for more than forty years, they are as well known now as they were when on ‘cleaning duties’. Doubtless the poster would have been used at Waterloo, among many other stations.

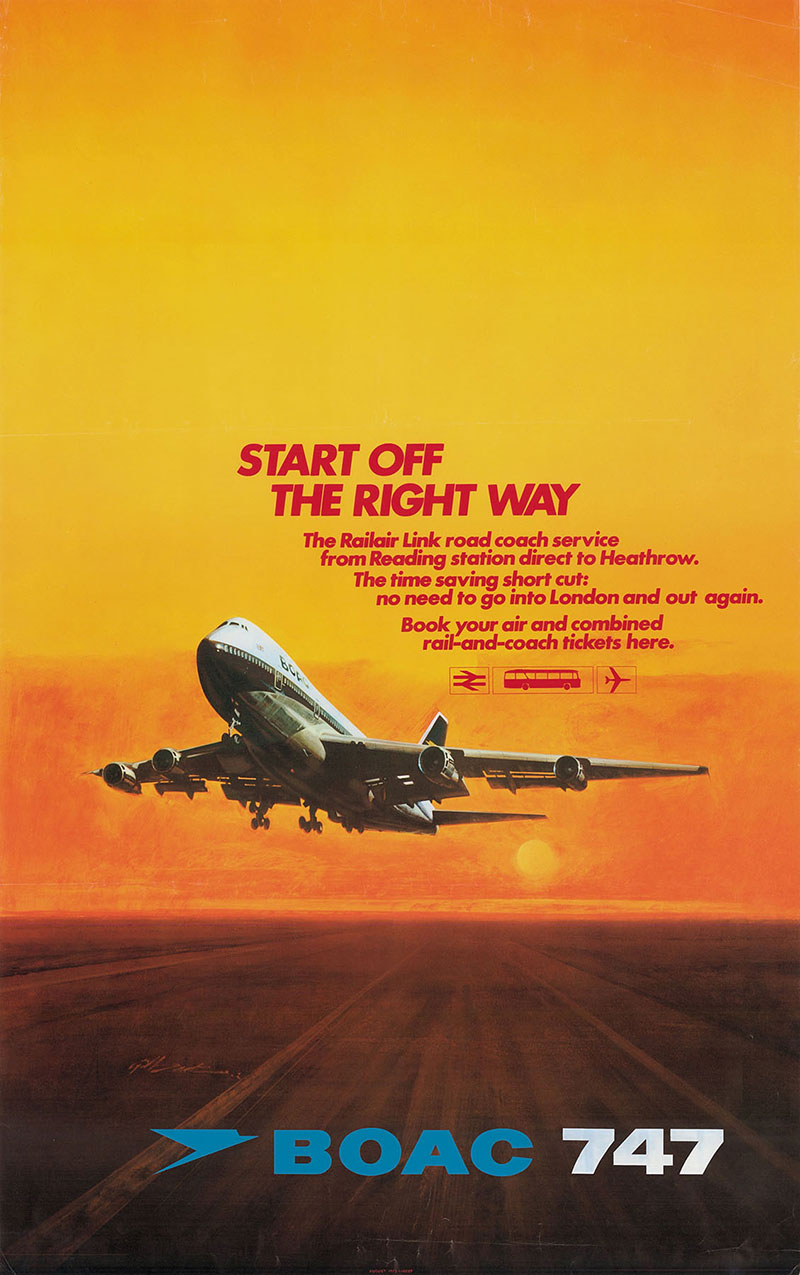

Next, from 1973, a poster promoting the Railair coach service from Reading Station to London Heathrow Airport which began on 6 March 1967. It is a powerful image showing a Boeing 747 just after take-off and uses a vivid low sun to light the sky above the aircraft. What makes the poster more remarkable is that 747s only flew in British Overseas Airways Corporation livery from April 1971 until March 1974 when British Airways was formed through the merger of the latter and British European Airways. BA flew these leviathans until the summer of 2020 when the COVID pandemic and the virtual collapse in international air traffic forced their early withdrawal.

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.