Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - October 2023 - Going Loco - October 2023

Going Loco - October 2023

FRIDAY 27 OCTOBER

Decoding the Past

Pictures of any Great Western Railway or BR Western Region steam locomotive in service will reveal a whole host of different codes for us to look at. There will be a series of oil lamps on the front and/or rear. Some have big numbers in a frame on the smokebox while others still have some fancy name to read. So, what’s that all about? I’m going to break it up into the four main areas:

Lamp codes

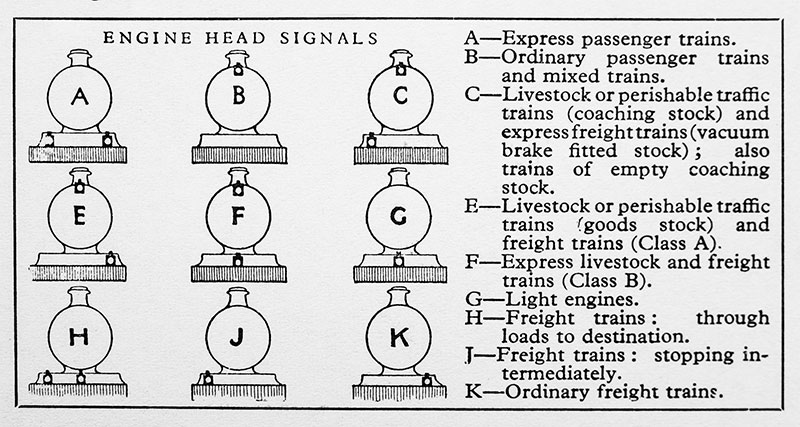

This explanation of headlamp codes was printed in the GWR’s book Cheltenham Flyer, published in 1934

By the 20th century pretty much all engines had four brackets for mounting oil lamps at the front and the rear of the locomotive. These lamp irons are spread three along the buffer beam and one at the top. The top one being either on the smokebox door or the top of the smokebox at the front and at the top of the tender or bunker at the rear. The lamps themselves were red until the mid 1930s and white after that. They have an oil burner inside and a lens at the front. There is a slot on the side that slips over the lamp iron and a pouch in the rear door that contains a red filter to change the colour of the light from white to red.

A pannier tank pilot engine with BR-era headlamp code, having brought in empty coaches to Paddington station in 1964

The lamp codes did change over time and there were specific rules that dictated how the lamps were to be used. A set of red lamps at the rear of any train was required so that signalmen could check if the train had split and left a portion on the line somewhere. The engine also must not carry a red rail light when hooked up to a train. For this purpose, additional lamp brackets were attached to the fireman’s side of the engine. The lamps would be blown out and turned to face the boiler so as not to cause confusion. Shunting engines at one point carried a red and white lamp each end to denote their constant backwards and forwards nature of their work.

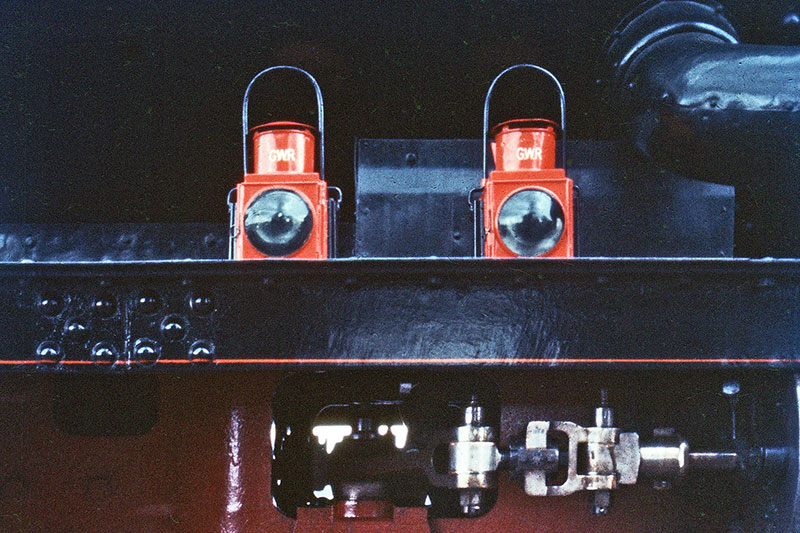

Two spare lamps on the fireman’s side brackets of Pendennis Castle at Taplow in 1967, when the loco’s frames were painted red!

Train reporting numbers

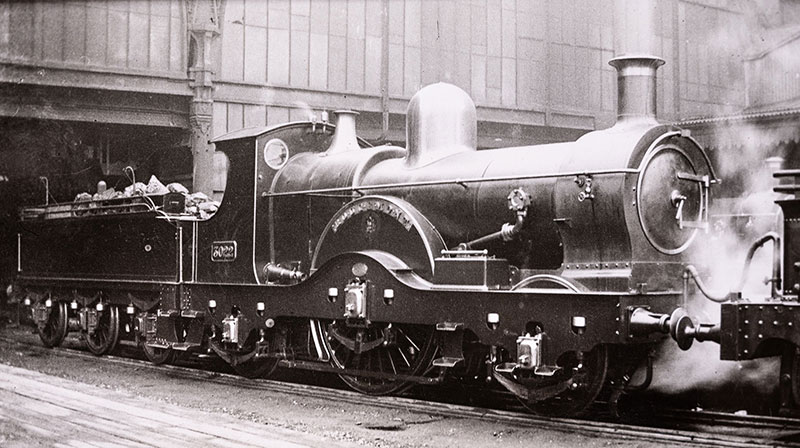

A publicity photograph to mark the introduction of reporting numbers on 14 July 1934

These were large white characters carried in a series of twenty inch black enamelled metal boards which fitted in a frame. This frame was mounted over the smokebox door handles. The system was introduced in 1934, with the massive increase in holidaymakers going to the West Country. There were so many people going there that extra trains – called relief services – were slotted in to the timetable. The large letters allowed all and sundry know where the trains were going. By 1936 the practice had spread and by the beginning of the Second World War, they were being used on a much more disparate set of services.

Hymek diesel-hydraulic No D7040 entering Devizes station with the 7.10 am Trowbridge to Paddington train in October 1964. The figure 2 in the headcode indicates it is a local passenger train and the A shows its destination as London. A BR standard 2-10-0 with a cement train waits for the token before moving off. Photograph by Philip Kelley

In the original version, the first figure was the origin of the service. Numbers 100 to 199 were from Paddington and 400 to 499 were from Bristol, for example. Each booked train number ended in either a 0 or a 5. If a train was to be run in more than one part, then the other numbers (1-4 and 6-9) were used. So, let’s work through an example. The down* Cornish Riviera Express was numbered 125 in the timetable. If the train was overbooked, a train would follow it bearing the number 126. If three trains were needed, 127, the fourth would be 128 and the fifth would be 129. In the up direction* from Plymouth the trains were numbered 615 to 619. In 1959, well after nationalisation, the whole of passenger services were added to the system. It’s why early diesels have the four-digit head code box on them (number, letter, number, number). The big change was that the first number represented the class of train and the letter was the destination. This system was displayed on locos until 1976 but is still used in one form or another electronically today. When you visit Swindon Panel in our Signalling Centre you will see the four-digit codes in use to identify the trains.

Named trains

The Cheltenham Flyer taking on water at Goring troughs on 14 September 1931

Some trains have names. We have already mentioned the Cornish Riviera Express and there were many like it. The Bristolian, The Flying Dutchman and so on. The GWR only used headboards (the name board that goes on the front of the engines) for selected of these named trains. The famous one being the Cheltenham Flyer. The winged GWR roundel and ‘World’s Fastest Train’ ribbon adorning the front of a Castle being re-created at Steam Museum, Swindon.

Train name and reporting numbers in one image. This photograph was taken on 17 July 1954 when Western Region was celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Cornish Riviera Express. The driver on left is Percy Steer and the fireman Aubrey Mitchell. The locomotive is No 6018 King Henry VI

British Railways Western Region, seeking to recapture some of that inter-war glamour, started making a big thing of the names trains again in the mid 1950s and started using headboards. The Bristolian was a famous example of this but many others had a cast metal plate hung on the smokebox lamp iron.

Specials

A Holiday Haunts Express in May 1933

Once upon a time, it was common for organisations and institutions to hire a train for a one off or limited series of excursions. Traditional headboards very much like the style of the named trains are common in late steam era photographs. The Stephenson Locomotive Society (SLS) being a common one. Sometimes these headboards took on a quite spectacular size, covering the whole of the front of the smokebox of the hauling locomotive! These were invariably made of wood and had a pretty disposable outlook as the trains were often only run once or for a short period of time.

An excursion on 28 April 1937 from Bristol Temple Meads to Slough for a tour of Pinewood film studios

One particular example we know the history of was run for visitors to the Huntley and Palmer’s biscuit factory in Reading. The great thing about this one is that our resident Reading aficionado, shopkeeping historian and guard extraordinaire, Mr Thomas Macey, has commissioned a replica of the headboard in order that we can re-create this look at Didcot. I’ll let him take up the story:

“Huntley and Palmer’s became the largest manufacturer of biscuits in the world from their purpose-built factory in Reading. It was also one of the first factories to use steam-powered machinery in the production of biscuits, together with the use of decorative metal tins. Factory tours were soon introduced to show the public the advances in biscuit production, and to drum up business! Special excursion trains were introduced that brought visitors to Reading station, where they would transfer to a bus service to the Kings Road entrance of H & P. Many of these trains would start at London Paddington and Swindon, stopping at stations en route to pick up passengers. The visitors would then return after the tour, having been given a supply of biscuits to take home!”

A Huntley and Palmer’s excursion to Reading

The replica Huntley and Palmer’s excursion headboard

Cheers Thomas! Although we don’t have an active Hall class engine to hang it on, I’m sure Thomas won’t mind ‘making do’ with Lady of Legend or Pendennis Castle .…

It may be of significance that Sir Ernest Palmer (First Baronet), a director of the biscuit firm from 1898, was also a director of the Great Western Railway. Thus Great Western Railway restaurant car menus invariably carried the words 'Biscuits provided by Huntley and Palmer's' at the bottom!

*Away from London. Trains that are travelling in the up direction are going towards London. If a service wasn’t going to London the up and down directions would be to and from the major destination.

FRIDAY 20 OCTOBER

The Pooley Weigh

Weighing things in the railway is of vital importance to the business – particularly when we consider the freight sector. Knowing how much you are hauling from place to place is vital. The accuracy of these measurements is clearly crucial. Too heavy and you are running the risk that the train is too heavy to pull. Too light and the train you provide is more than needed – wasting horsepower and causing wear and tear on rolling stock that needn’t happen.

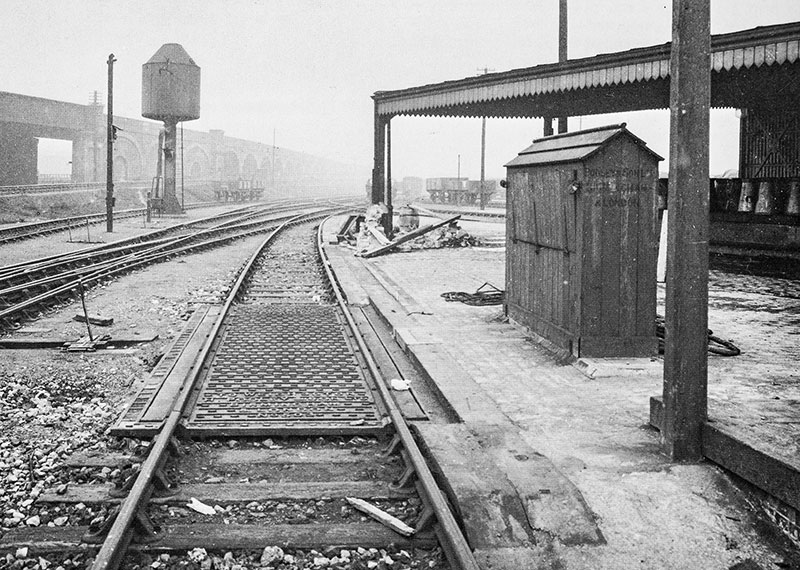

The railway wagon weighbridge at the GWR’s South Lambeth goods depot. Photograph published in A Pictorial Record of Great Western Architecture by Adrian Vaughan

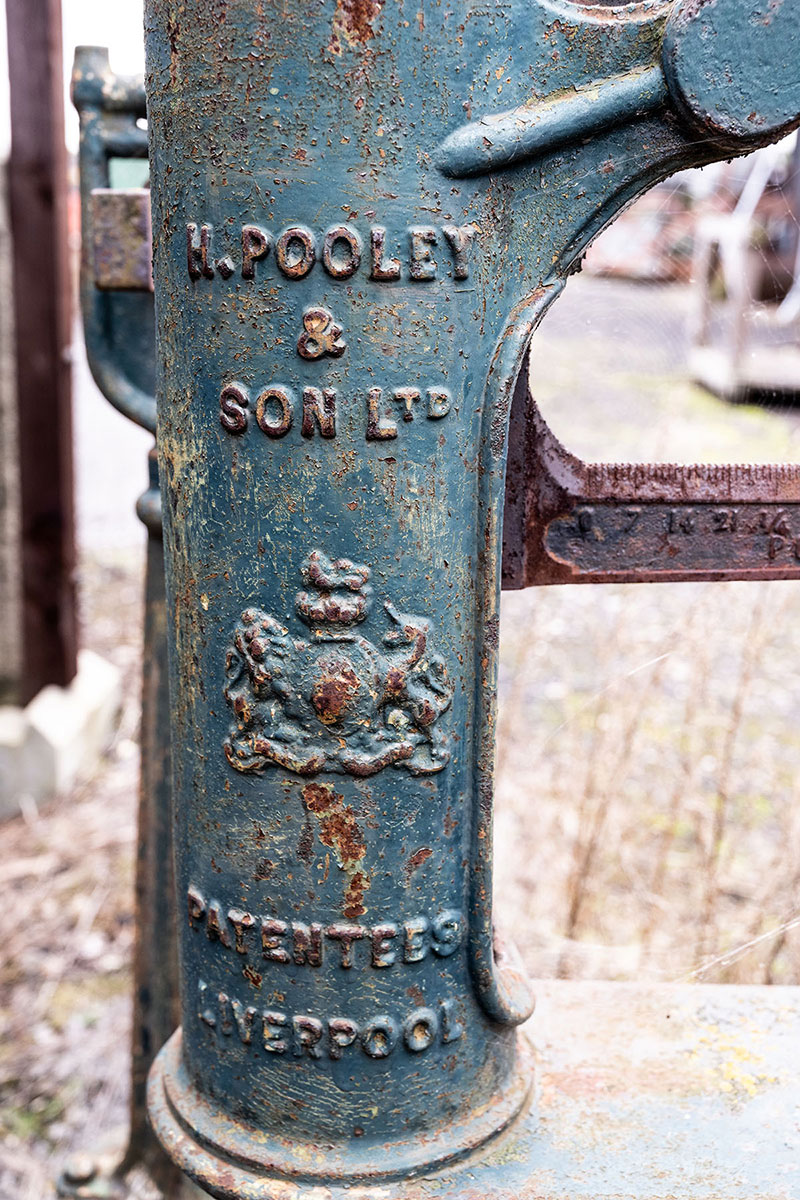

In the pursuit of the perfect balance*, there was one company that stood head and shoulders above the others. That was the Liverpool (and from 1896 Birmingham) firm of Henry Pooley and Sons. This was a long established company that dated back to the 18th century. Henry Pooley Senior set up in about 1790 as a manufacturer of scale beams (weighing machines). They were clearly busy as Henry Pooley II, the son of the original, became a partner in the business in 1830. This was about the time of the birth of the railways and they saw opportunity knocking .…

A Pooley machine from the Liverpool era, awaiting restoration at Didcot Railway Centre

The railways were the coming thing - dozens of them were cropping up all over the country in a period known to historians today as ‘railway mania’. Clearly, the ability to serve this booming market was a great financial move. They produced their first platform weighing scales in about 1835 from their works at The Albion Foundry. About this time, they also produced their first weigh bridge for railway vehicles. This is almost exactly as it sounds. It is a section of track that is mounted on what is essentially a giant set of scales! The rail vehicle is shunted onto the floating section of track and it is weighed. If you know the unladen weight of the vehicle and the weight it is now, you can work out how heavy the load is by subtracting one from the other.

A Pooley machine from the Birmingham era, awaiting restoration at Didcot Railway Centre

By the mid 1930s, they accounted for over 90% of all the weighing gear on the railways of Britain. This was despite the company being absorbed by W & T Avery in 1913. The name was simply too big to see lapse. At their height, Pooley employed one and a half thousand people. The dominance of the firm in the market led it to be a working partner in the day-to-day operations of the railway. So much so that it lead to it having its own rolling stock. The ‘Pooley Van’ was quite a common thing on several railways but the Great Western had a couple of different designs, a few of which survive in preservation. The idea was to give the company a series of mobile workshops so that their testing and calibration equipment could be transported from place to place with ease.

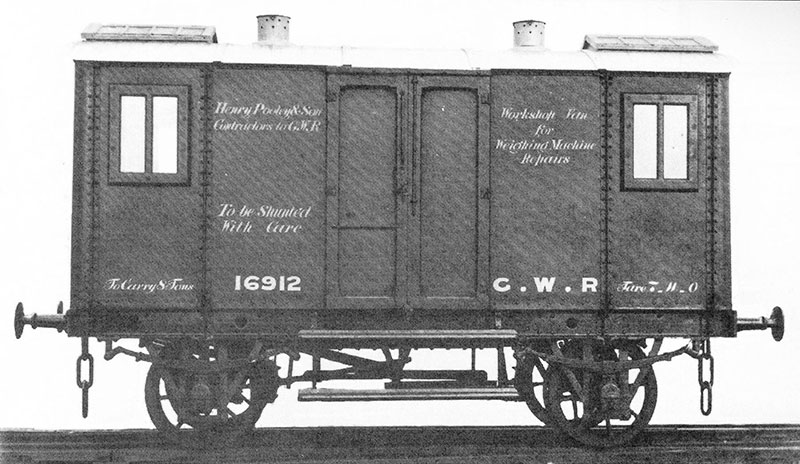

Pooley van No 16912 built in 1899, of the same diagram as the 813 Preservation Fund’s 16908. Photograph published in GWR Goods Wagons by A G Atkins, W Beard and R Tourret

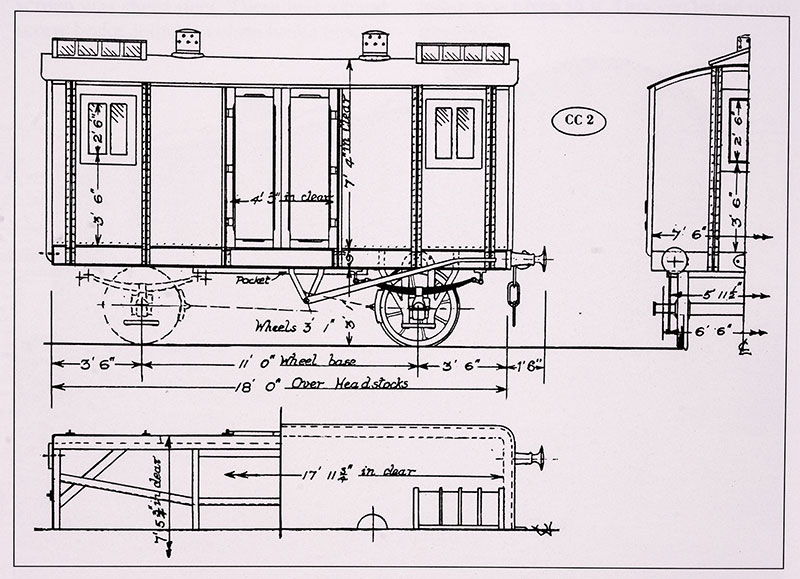

Our friends in the 813 Preservation Fund have vehicle No 16908. This is an example of a workshop van that was purpose built from the beginning. It was built under diagram CC2 as part of Lot 487 in 1905. A total of 6 were constructed between 1899 and 1906. This thing looks for all the world like an oversized IRON MINK type vehicle. It is much taller and longer that the IRON MINK but follows much of the same design cues. This had a capacity of eight tons, so it was clearly intended to take quite a bit of tooling and equipment!

Drawing of a Pooley van to diagram CC2, published in GWR Goods Wagons by A G Atkins, W Beard and R Tourret

Originally it had six windows, two in each side and one at each end. It had a skylight at each end too to provide as much natural light as possible for what was probably pretty fiddly work. When the sun was switched off**, there were oil lamps with roof vents at each end too. It survived into preservation by becoming an internal user vehicle at British Steel’s Llanwern Works in Newport, South Wales. It was saved from there in 1995 but it is still in a derelict condition. Diagram CC5 was essentially a wooden bodied version. There were four built between 1909 and 1920.

Pooley van No 82917 at Didcot Railway Centre

In 1922 Swindon converted an existing meat van that came from the Cambrian Railway. This became No 37458. After this, the final versions of these wagons built for Pooley were conversions of existing freight vehicles. The first was a 1922 conversion of diagram V11. This was a MINK D covered goods van with an 18’ long wheelbase. After that, the last four, of which we have one at Didcot, were conversions of diagram V12 MINK vans undertaken in 1934. Ours was originally built as a standard covered goods van in 1911. Like all the other conversions, six windows and skylights each end were provided. Presumably the additional windows in the doors were a later addition.

More Pooleyana at Didcot Railway Centre

No 82917 was purchased by a society member, David Rawlinson. It was originally preserved at Steamport Southport. When he passed away, his will kindly stipulated that the small collection of GWR freight vehicles he had amassed were to be donated to us at Didcot. Restoration began with the North West group of the society undertaking initial conservation work at The Railway Age museum at Crewe in March 2004. The vehicles moved to Didcot in October 2008 and No 82917 is rather pleasingly in what I refer to as a state of pure preservation. It was converted to become a workshop vehicle and that is still what it is used for! It has been cosmetically restored on one side and looks magnificent after the attentions of Ann, our ‘wagon dabbler extraordinaire’! No doubt a full restoration will be required one day, but for now, it soldiers on doing the job it was intended to do nearly 90 years ago.

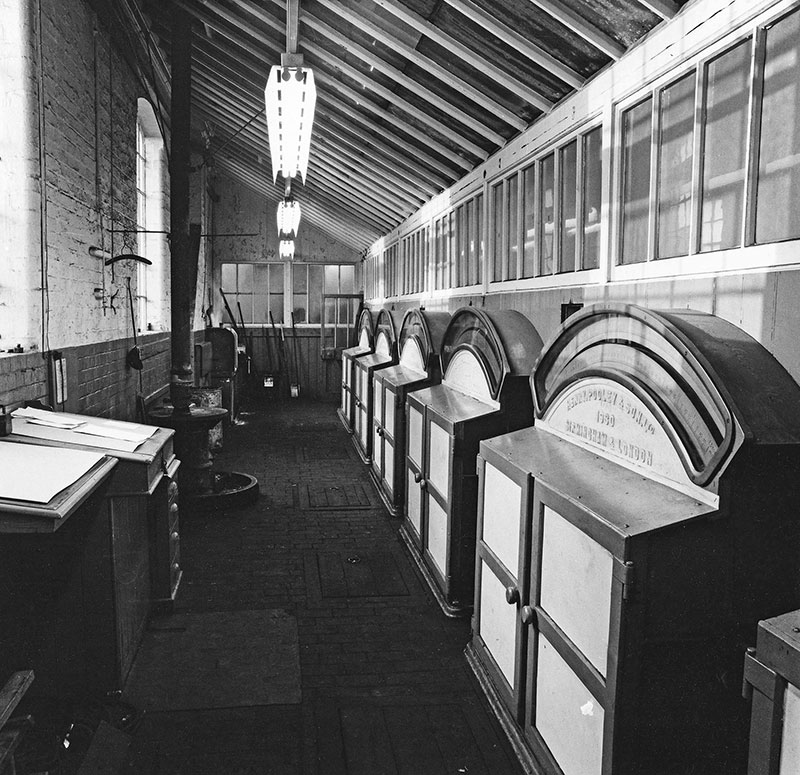

The weigh house at Swindon Works was provided with six Pooley weigh tables (five shown here) so the weight on all axles of a locomotive could be measured simultaneously. Each of the Pooley machines had twin scales to show the weight on both wheels of an axle

* That’s a scales joke right there .…

** Technically known as night time.

FRIDAY 13 OCTOBER

The Pioneer’s Progress - Part 9

Exciting news from Planet 0-4-2! In another of our special updates from Project Manager and Going Loco Roving Reporter, Phil, we take a look at the goings on with the overhaul of our wonderful pioneer locomotive No 1466. Take it away Phil .…

1466 at Didcot Halt in the 1990s – the perfect sleepy country branch line scene that so many enthusiasts were inspired to re-create in the 1960s

Thanks Drew!

To say it has been a very busy time since my previous update, may be a bit of an understatement .… There has been a plethora of jobs well underway and indeed a number finished as well. This includes the organisation of everything from BES inspections (our boiler inspectors and insurers) to ordering materials needed between workload packages. As a result everything is progressing superbly well with 1466 at the West Somerset Railway (WSR) with Ryan and his team.

I’m very glad to say that the copper tube plate mentioned in my previous report did indeed thankfully arrive from South Devon Railway Engineering, albeit one week later than anticipated. You don’t mind a week late if you get a great product and the pressing is superb. Rather that than rushed .… After a thorough check over by us and BES, it has passed inspection without fault – Phew!

Since the tubeplate arrived it’s been full speed ahead in getting the inner-copper firebox back together again and making sure everything fits ‘true’ once more. With a bit of fettling here and there, plus many many rivet holes drilled, it’s good to finally see the inner-firebox and foundation ring back together once more.

Where are we now? Well, after the latest BES inspection, the alignment of the copper firebox has been approved and signed off. So now work on riveting it all back together can commence. Then the job of putting it back in the boiler and aligning it all up, followed by a mass of further drilling and tapping with a huge amount of stays then to be fitted.

The copper inner firebox, upside down for convenience – clockwise from top: the tube nest, a staggering 195 holes for the boiler tubes; Matt reaming the many stay holes; the new tubeplate fitted into the copper wrapper

In the meantime, Ryan and team have started to ream out the side stay holes on the copper-wrapper. They have also pilot drilled all the stay holes after a couple of days thoroughly marking out the copper doorplate and tube plate. This was done taking into consideration various measurements and data from the original platework, and of course original Swindon technical drawings from our very own archive.

You may remember in my last update that on the previous inspection we had hydraulically tested the regulator tube and steam pipes. Here, a couple of leaks were found and some minor repairs were needed. We all agreed a repair method and we settled on a simple brazing procedure. These repairs have been carried out and completed and thus, on the latest BES inspection, they have all passed their second hydraulic test without issue!

Left: the regulator box and steam pipes set up as a rig to be hydraulically tested. Right: a small crack between surfaces where the pipe and the atomiser sit has been repaired

Alongside all that, several other avenues have been walked down. The safety valve and its associated parts were stripped down for inspection. It’s now back together again having received four newly made pillars and two spindles. It is fair to say that it’s in the best condition it has been for years and is set to last for many years to come. The new blower ring casting which was delivered to WSR in the last update is also shortly to start being machined now that the required tools are available. So that will see another big little job ticked off once completed!

The safety valve, left to right: new pillars being manufactured; brand new set of spindles and pillars; safety valve fully assembled

The last big boiler job now is the ordering of the all-important parts so they can be fitted and the boiler tested. We needed the material for the steel side stays to go in all those holes drilled, tapped as mentioned earlier. We have also started the process into sourcing the 195 boiler tubes (2 large flues and 193 small tubes) needed for our little pioneer. Rather excitingly and finally for this report, we will soon see the locomotive’s chassis going into the paint shop for prep and a spot of paint...

Brilliant stuff – cheers Phil! There are some exciting time ahead. The return of our pioneer means so much to the society. Alongside the obvious history we have with this machine, it will also see the return of the demonstration of auto working at Didcot. The last time this quintessentially GWR practice was regularly shown was while Steam Railmotor No 93 was in traffic .… As always, if you can help at all with a donation, that would be most welcome.

See you next time!

FRIDAY 6 OCTOBER

A Singular Locomotive

Large single driving wheels were a common feature of early express locomotives. The early Great Western Railway engines like our replicas of Fire Fly and Iron Duke make this plain. In fact, the 2-2-2 wheel arrangement was used at Swindon for a very long time but as time went on, the basic flaw in the design was revealed. As trains got heavier, the single wheel became more likely to slip and when it did, that was it! No more forwards .… The last 2-2-2 design built at Swindon was the 3001 class designed by William Dean and his team in 1891. The driving wheels on these engines were no less than 7’ 9” (2.362m) in diameter. They had inside cylinders of 20” (508mm) in diameter and 24” (610mm) stroke.

A 2-2-2 of the series 3021-3028, running on the broad gauge at the west end of Sonning Cutting in May 1892

The interesting bit about their cylinder blocks was that the valves were placed underneath the cylinders. This design used slide valves and these only seal and push against the valve faces when the steam is going into the cylinders. The good thing about this arrangement is that when the steam is not flowing, the valves fall down, away from the valve face and this means the engine can roll more freely and that wear is only incurred when the steam is flowing. Clever stuff! These large diameter cylinders were able to be put inside the frames because the locomotive was arranged with outside frames. Frames that sit outside the driving wheels.

No 3022 Rougemont as a 2-2-2. She had been built in May 1891 to run on the broad gauge, converted to standard gauge in July 1892 and rebuilt as a 4-2-2 in July 1894

The thirty engines were built in two distinct batches. Twenty-two were built to the standard gauge in 1892 were numbered Nos. 3001-3020, plus 3029 and 3030. The second batch of eight were built to be ‘convertible’*. They actually appeared in 1891 and were initially produced as broad gauge engines with the wheels on the outside of the now inaccurately named outside frames. Despite the fact that the 7’ 0¼” gauge sections of the GWR were to be closed and converted to standard or 4’ 8½” gauge in 1892, services had to be maintained until the end and the locomotives available at the time were on their knees – worn out due to the lack of investment in broad gauge machinery for obvious reasons. They were all converted to standard gauge on the abolition of the broad gauge and the outside, inside, outside** frame conundrum was resolved.

No 3031 Achilles with a westbound express at Acton

The problem with a heavy, modern locomotive with a 2-2-2 wheel arrangement became clear on 16 September 1893 when, while speeding through Box Tunnel with an express train, No 3021 Wigmore Castle broke her leading axle and derailed. Excessive weight at the front end was thought to be the problem so the locomotives were all rebuilt with a four-wheel bogie at the front. The issue here is about those clever valves. There was no way to put a centre pivot pin in there and still be able to get to the valves to check and maintain them.

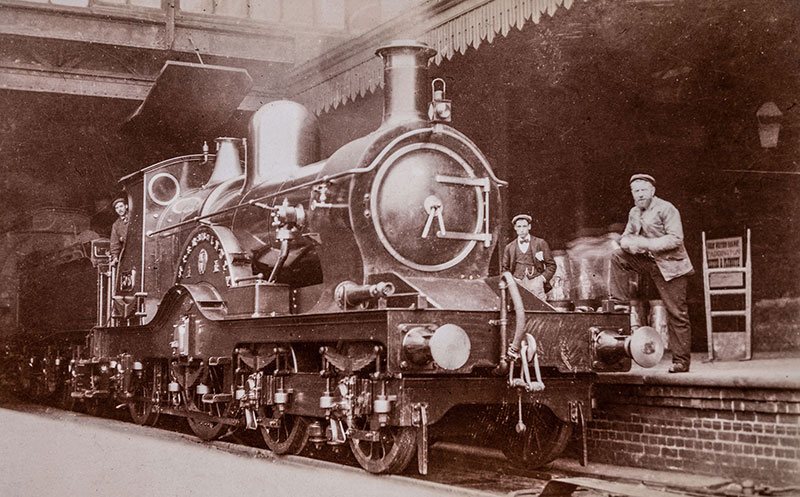

No 3040 Empress of India at Paddington

Dean is now known for his use of the centreless bogie where the bogie of a locomotive or coach is suspended on a structure around the outside of bogie. Our Railmotor No 93 and some of our vintage coaches have one version of this system. The loco one used here was different but works in a similar way – another example of the aforementioned clever stuff! The rebuild of No 3021 was completed in March 1894 and the rebuild of the other members of the class was completed by December of the same year. So successful was this update that a further 50 of the new 4-2-2 design were built new. There were a few differences, cylinder bores went down to 19” (403mm) diameter. Slightly thicker tyres were fitted to the driving wheels of all engines to slightly increase the driving wheel diameter.

No 3065 Duke of Connaught, the record-breaker from Bristol to London

These engines were fast. No 3065 Duke of Connaught made a run on the famous Ocean Mail service on 9 May 1904. The same day and indeed the same train that No 3440 City of Truro had just broken the 100mph barrier on for the first time. Duke of Connaught took over from No 3440 at Bristol and made a dash to London Paddington in just 99 minutes. The total Plymouth – Bristol – Paddington service having taken just 227 minutes.

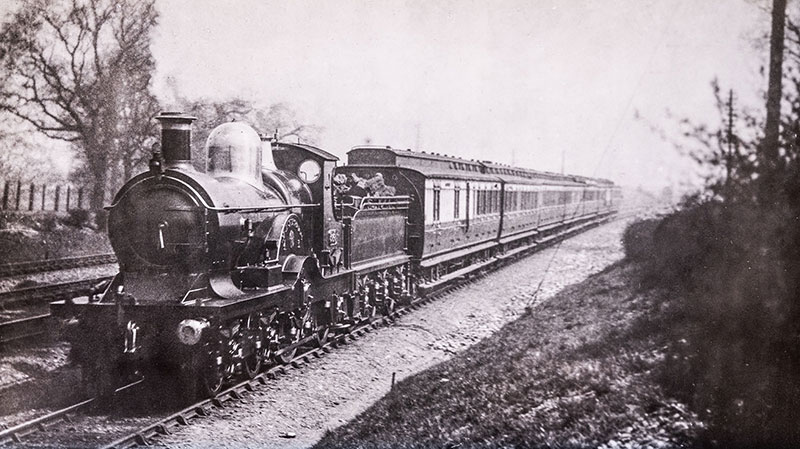

No 3040 Empress of India at Whiteball, with a travelling post office vehicle at the front of the train

No 3048 Majestic on a westbound Bath and Bristol train

They were, however, only on the top of the heap for a very short time. Even Swindon’s superior technology couldn’t save them from the basic flaw that trains were getting too heavy for just one set of driving wheels. New boilers were tried and improved steaming but they still just had one set of driving wheels. Long travel valves were suggested but there wasn’t the space to fit the larger eccentrics and they still had just one set of driving wheels. An attempt to design a solution that turned them into 4-4-0s with 7’ 2” (2.184m) driving wheels was turned down as there wasn’t the clearance needed to fit the connecting rods. They were clearly loved at Swindon and several other suggestions were made. All fell to nought and in the end, their withdrawal became inevitable. The first went in 1908 and the last, No. 3074 Princess Helena, went in December 1916.

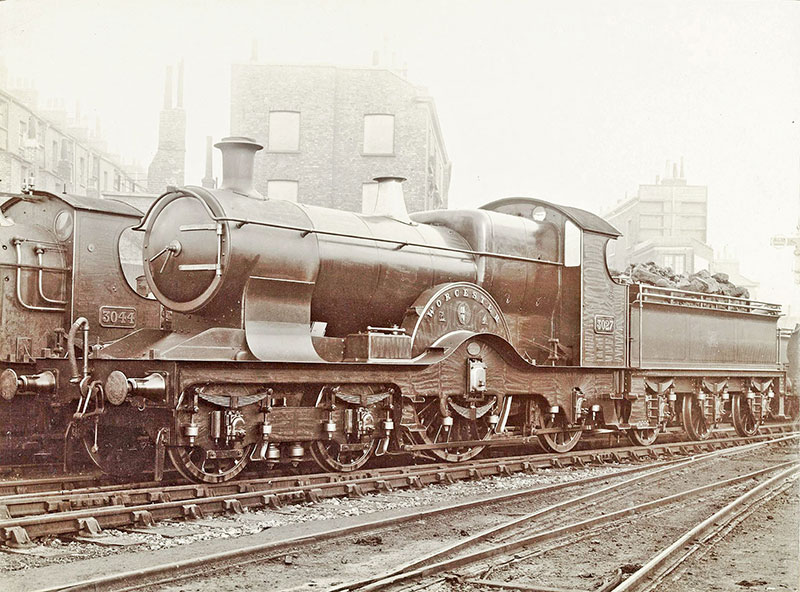

No 3027 Worcester rebuilt in 1900 with a non-taper standard No 2 boiler, including Belpaire firebox, and wide cab (covering part of the rear leaf spring)

No 3050 Royal Sovereign with a bogie that has coil springs in place of leaf springs

They are a bit like the tragic famous celebrity that dies young and becomes a legend as a result. In terms of their looks, they were beautiful machines. A famous Hornby/Tri-ang model was made many years ago and is still sold today. They had flowing lines and looked every inch the refined locomotives that they truly were. They personified all the elegance of the late Victorian and early Edwardian era in which they existed. But, like many of those tragic celebrities, they had a fatal flaw. The single wheeler had had its day. Despite their early scrapping date, we can at least get an idea of how one of these engines might have looked.

No 3060 John G Griffiths fitted with Belpaire firebox and top feed boiler, plus wide cab. Griffiths was a GWR director, the locomotive had been named Warlock until 1909

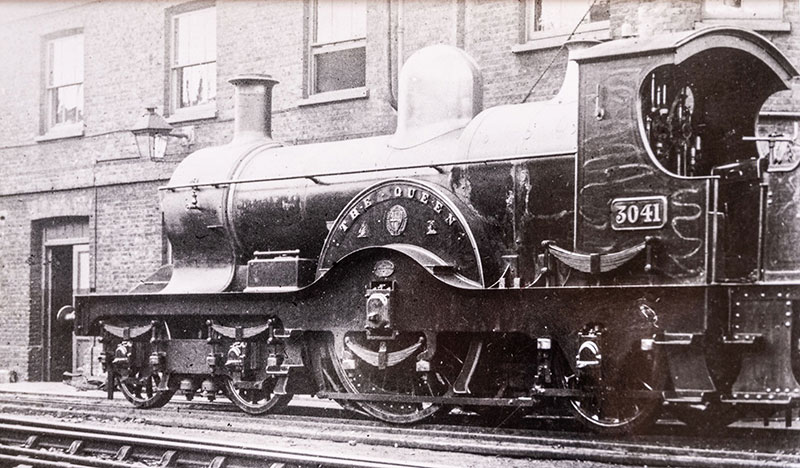

A static replica was constructed for the now defunct Railways and Royalty exhibition that was sited in Windsor station from 1983. It did have a tender but that was scrapped when the whole station was converted into a shopping arcade. The engine selected was, appropriately, No 3041 The Queen. And there she still sits. Next to a restaurant. A reminder of a more elegant age and a locomotive class that lived fast and died young.

No 3041 The Queen, the original locomotive, which was given the name during Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee year in 1897, and carried it until 1910 when she was renamed James Mason – after a GWR director

* This does not mean that it had a canvas roof that you could wind back to enjoy the sunshine .…

** Sounds a bit like a Beach Boys song .…

|

|

|

|

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.