Home » Other Articles » Going Loco Index » Going Loco - December 2023 - Going Loco - December 2023

Going Loco - December 2023

FRIDAY 22 DECEMBER

Late breaking Going Loco news! Photo Frank has been in the archives and has pulled out a seasonal tale for us to all enjoy! Take it away Frank…

Here’s a bonus for all you Going Loco readers. Searching through the Great Western Railway Magazine for something Christmassy, we chanced on this evocative article in the March 1939 edition describing an auto-train* journey from Trowbridge to Chippenham on a Saturday night 85 years ago. Written by R J Blackmore, a regular contributor to the magazine, it is a beautifully-observed description of the characters and rituals of the journey long ago. We advise you to sit back with a cup of coffee or glass of wine and let this eloquent essay take you back in time.

Auto-train Journey: A Saturday Night West-Country Idyll

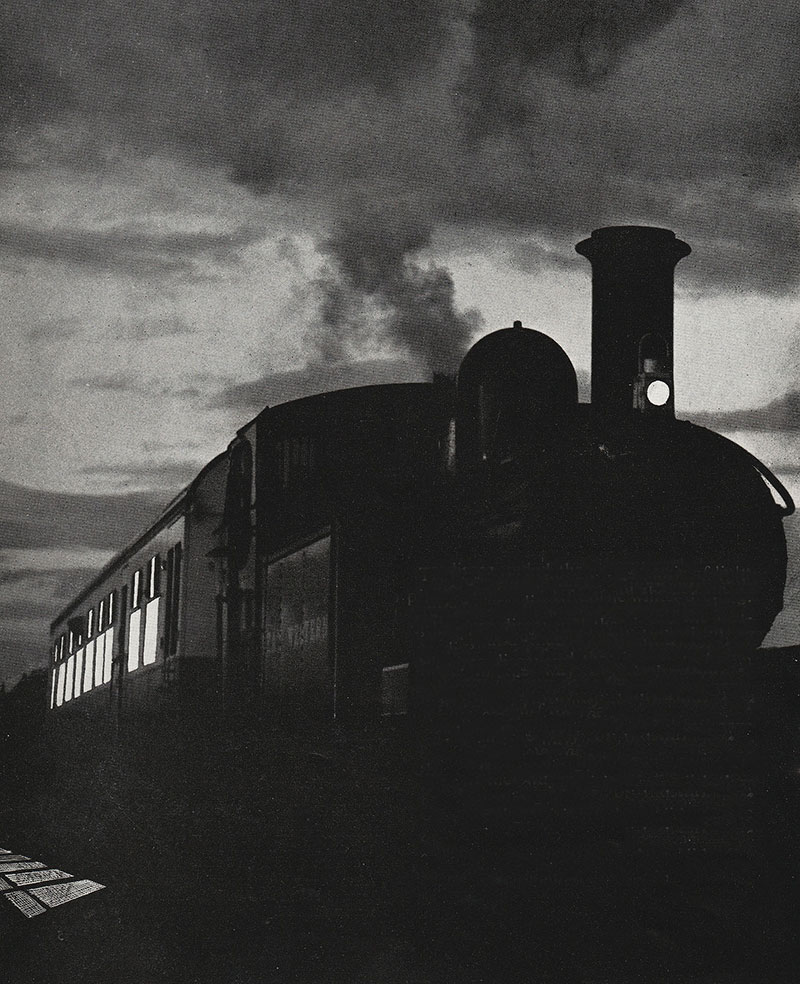

R J Blackmore’s Auto-train Journey was reprinted 55 years ago in Great Western Echo, Winter 1968 edition, using this image of Didcot’s 0-4-2T No 1466 and auto-trailer No 231 as an illustration

Trowbridge station was an oasis of light in the misty gloom of the winter evening. I passed the barrier and crossed the footbridge, and then with a mild thrill of pleasure discovered that it was to be an auto-trailer journey to Chippenham. Perhaps I am biased, but every time I visualise the picture which met my gaze as I stood for a second at the foot of those steps, I feel that nothing ever attempted in the way of illustrating a Christmas greeting card could capture better the spirit of English homeliness and friendly invitation than did that cheerful well-lighted auto-train.

“English homeliness and friendly invitation in a cheerful well-lighted auto-train”. Guard Thomas Macey and auto-trailer No 190 at Didcot Halt

The big open compartment which I entered was comfortably full, and it was Saturday night. I say it was Saturday night significantly, because there is no use denying that this night is a sort of English institution, and somehow or other it makes all the difference to folk. Unless a man was either jaundiced or “superior”, the atmosphere of that coach was one to gladden his heart. There was no possible doubt about the friendly warmth of fellowship which prevailed. Somehow we were all one; somehow we were all happy. Many were obviously well-acquainted with each other, and yet the unacquainted seemed to be on an equal footing. Whatever the jest, and no matter from what remote corner it emanated, laughter was general and hearty. There was no feeling of restraint, and the atmosphere was as different from that of the average compartment of a fast train as chalk is from cheese.

I have never warmed toward my fellow-countrymen more, nor ever felt more satisfied to be a son of the West. Even the man who laughed at his own jokes wasn’t the bore that such men usually are. In appearance he was a cross between an old salt and a gamekeeper, and he kept his immediate audience in spasms for upwards of half an hour, while his own laugh rang out the loudest of all. The guard, who appeared from time to time framed in the vestibule doorway, invariably became the butt of the jovial one, but he carried on with his job with an air of amused tolerance. There were also the members and committee of a football team, who by their comments on the afternoon’s play had sustained defeat by reason of a succession of mishaps which left no doubt that some malignant force had been fighting against them – besides the opposing eleven and the referee.

At one end, where the seats faced each other, a party of some sort regaled themselves with hot chip potatoes, hurriedly purchased before reaching the station: the savoury smell mingled with the tobacco clouds and drifted not unpleasantly about our heads. There were market-women with their brimming baskets, men with coloured newspapers, small children with bulging cheeks and munching jaws, people with week-end cases, sports-bags, small parcels, boxes, bunches of flowers; and there was also a solitary angler, complete with tackle. A sprinkling of the occupants were what an old Wiltshire lady used to call ‘bettermous’ people, but even they were in spirit with the occasion.

With its own inimitable impetuosity the auto-train – always accelerating rapidly – hustled from one halt to the next. The little ceremony which was performed at each wayside halt was worthy of the pen of Dickens, for after seeing all was well with his charge, the guard proceeded to lock up the tiny station and solemnly turn out all the platform lights. With the extinguishing of each last light the outside world was plunged in darkness except for the square patches of light thrown out by the carriage lamps. In one of these patches we could just distinguish the shadowy figure of our guard, with one foot on the vestibule step and with his left arm holding his lamp aloft. The side we could see showed red, but I knew that our unknown friend at the throttle saw green, for we would immediately burst into motion and the guard would swing in to his vestibule from the gloom outside.

We drew in at length at Chippenham station. We all rose from our seats, collected our belongings and swayed in an animated procession along the gangway – merging in the vestibule with the crowd from the other compartment and down on to the platform. A few minutes later I watched the same auto-train, now dejectedly empty, shoot off into the night, presumably to its roost. The station seemed to grow suddenly colder, and with little enthusiasm I waited for the ‘fast’ which would take me home. – R. J. Blackmore.

Passengers inside auto-trailer 190

* Auto-trains are pushed or pulled by a small tank engine using auto-trailer coaches with a cab from which the driver can control the regulator on the engine and the vacuum brakes, while the fireman remains on the footplate. There are normally one of two coaches on an auto-train, although there can be up to four with the engine sandwiched in the middle. The ability to push or pull the train does away with the need to uncouple the engine and shunt it to the front of the train after each journey.

Thanks Frank! In what may turn into a tradition, we find ourselves in need of new lyrics to a seasonal song to suit our Swindon persuasion. I present to you, the 12 Days of Swindon Works Christmas. Best singing voices now everyone…

And with that over (thank goodness - I’m no songwriter!), this really is Going Loco signing out for 2023. From the team, Have a very happy Christmas and a peaceful and prosperous new year!

FRIDAY 15 DECEMBER

A Bit of a Slip Up?

The Great Western was quite the innovator during its existence. It pursued many technologies that were the precursors of practice on the modern railway. Although they didn’t invent many of them, they were early adopters. Auto-working, diesel multiple units and the concept of what we know today as Crossrail/the Elizabeth Line to name a few. One type of technology that didn’t catch on, however, was Slip Coaches. It is a remarkable technology, however, and therefore well within our remit here in Going Loco!

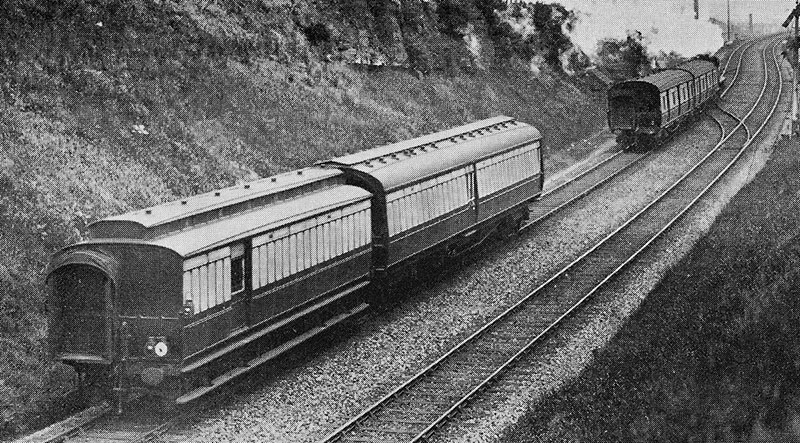

Ocean Mail vans from Plymouth being slipped on the approach to Bristol before continuing their journey northwards, while the train continues to London without stopping

What is remarkable about this technology is that there has been – quite understandably – a great deal of effort put into making sure that trains don’t have coaches or wagons fall off the end as you go along. Whereas slip coaches do this very thing. They intentionally fall off the back end of the train. It’s a bit mad when you first hear about it, but this really was a thing. The idea was that to make things more efficient and generally speed trains up, you had a special coupling on a coach that allowed it to be detached at speed. You could therefore have an express service to stations that would not have otherwise been able to have them. It’s not quite as simple as this and we will see why in a while .…

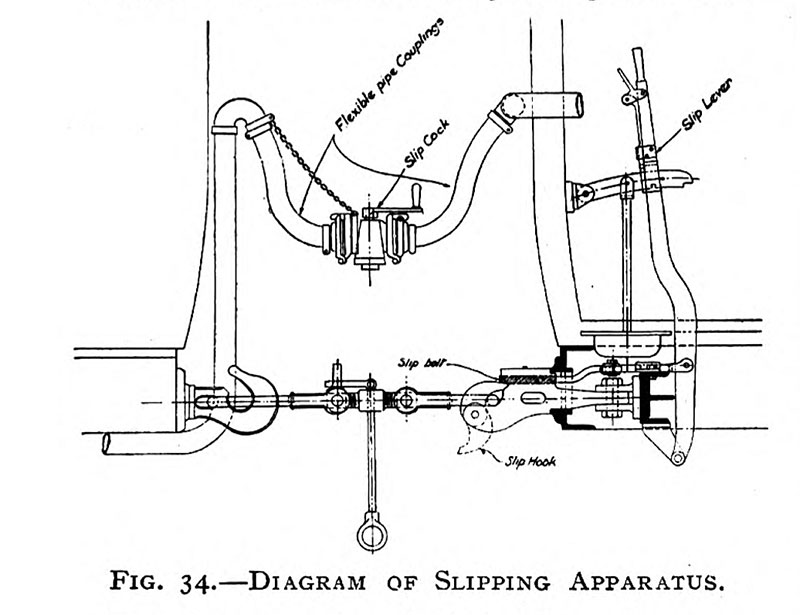

This diagram of the slip apparatus was published in the Great Western Railway Magazine, January 1907 edition

The first slip coach operation performed at speed was done on the London Brighton & South Coast Railway in February 1858. The London Bridge to Brighton express slipped coaches for Lewes and Hastings. The Great Western was clearly not to be outdone and ran its first slip trial on 29 November 1858. This service was a London Paddington to Bristol service that slipped coaches at Slough and Banbury. Then a Paddington to Birmingham service slipped coaches at Banbury in December of the same year. Quite how safe this was back in the day one has to wonder. Still, pioneering stuff .…

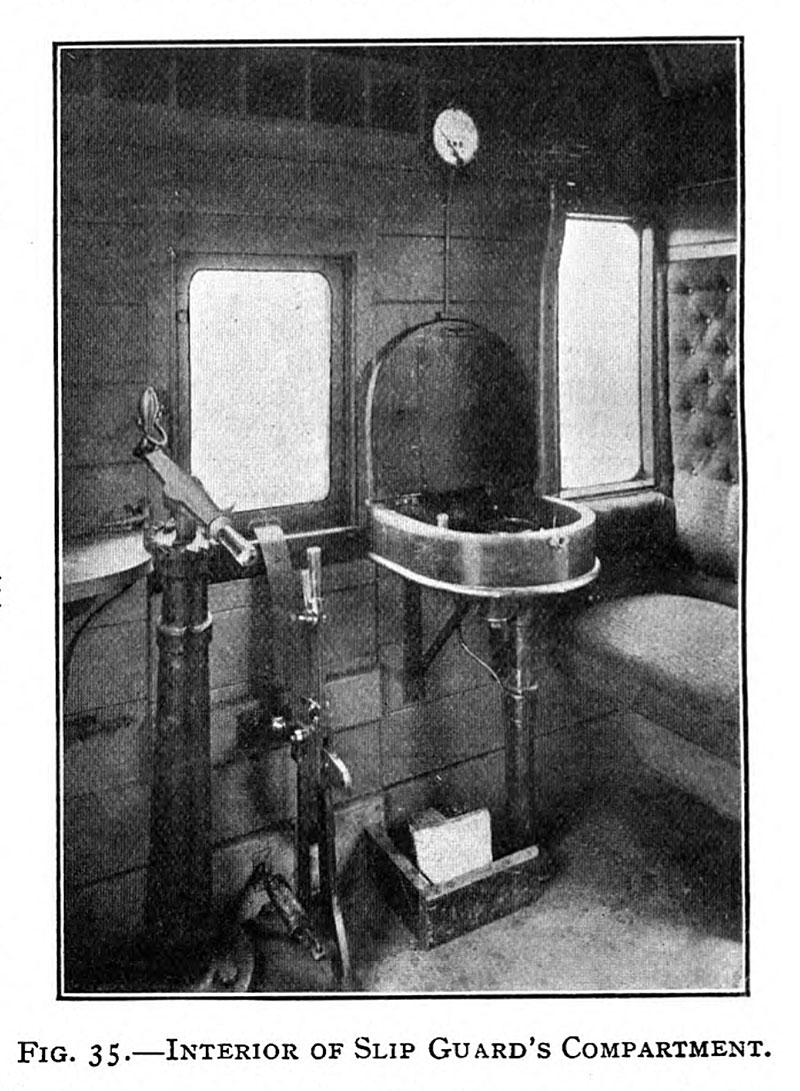

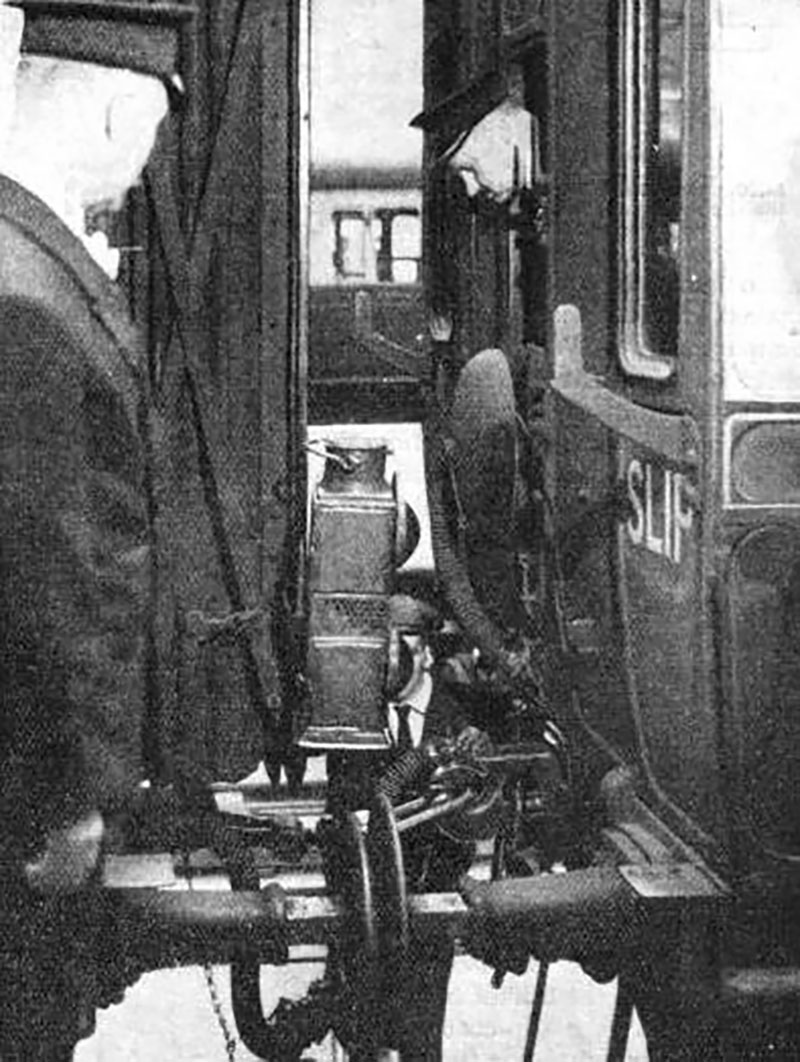

This photograph of the interior of the slip guard’s compartment was published in the Great Western Railway Magazine, January 1907 edition

Slip coaches developed a technology all of their own. They could run on their own but equally they could run with a few regular coaches behind them as well. The slip coaches could also be single or double-ended. They could have a single slip end without a corridor and a corridor end at the rear. Splitting the corridor was only done very briefly prior to WWI, by the London & North Western Railway. Other types had slip working gear at both ends. The slip ends were equipped with a hinged coupling. A slip bolt held it in place and, when the lever in the coach was pulled, the bolt was pulled back and the hook hinged down, allowing the coupling of the coach in front to slip off.

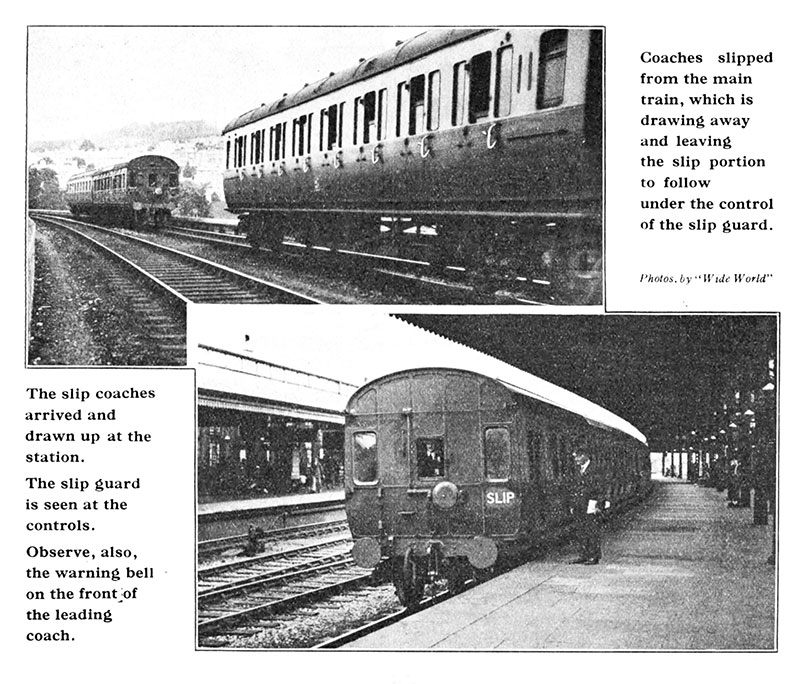

These photographs of a slip taking place were published in the Great Western Railway Magazine, December 1934 edition

There were also special self-sealing valves fitted in the ends of the vacuum brake hoses. This was needed to prevent air getting into the brake systems of both the train and the slip portion. That would cause the brakes to come on immediately and cause the whole ensemble to come to a grinding halt. With a skilled guard, the slip portion could be brought to a gentle halt in the desired station. From there it was picked up by a waiting locomotive, or horse in the early days. And this is revealed the biggest Achilles heel of the slip coach system. The unequal working. So, we now have our express train coaches at their destination. The big issue is that you cannot pick them up again at speed! They have to be worked back on a different train.

The slip guard watches while the shunter checks the coupling. Note the double lamp on the rear of the main train

Despite this, up until the start of the Great War, there were 72 slip coach operations every day during the week. The war put paid to all this. The lack of personnel hit the railways hard. A train with a slip portion needed two guards, not one. As such the services were suspended for the duration. They returned after the war but they were never as numerous as in their heyday. A famous example was the Cornish Riviera Limited. This train ran from London Paddington to Penzance but had slip portions that that was slipped near Westbury for Weymouth. Another was slipped at Taunton. The final one was slipped at Exeter and worked through all stations to Kingswear. The service proved so popular in the summer months that the slip operations were sometimes abandoned and extra trains were run instead to the intermediate stations!

A double lamp of the type that was placed on the rear of the main train to show signalmen that the slip had taken place. Lamp in the Great Western Trust collection at Didcot Railway Centre

As before, the Second World War put paid to the practice for the duration and post-war it only made a comparatively lacklustre return. Just five per day were completed. Slip working lasted well into the British Railways era after nationalisation but the final slip working of a double coach happened at Didcot on 7 June 1960 and the very last single coach slip on the Western was performed Bicester North on the 10 September 1960.

A double lamp showing red and white lights that was placed on the rear of the slip carriage. Lamp in the Great Western Trust collection at Didcot Railway Centre

Remarkably, this seemingly very dodgy practice resulted in very few accidents. The eminent railway historian Adrian Vaughan uncovered an example in his researches. This occurred in heavy fog at Woodford Halse in 1935. The coach was slipped and then the train it had been released from had to slow down. Unable to see this, the guard ran into the rear of the coaches. This was typical of the accidents with this practice.

A coach being slipped from an eastbound express on the approach to Didcot. Photograph in the Great Western Trust collection

The lack of a corridor connection means that the on-train facilities such as restaurant coaches cannot be accessed by passengers in the slip portion. However flawed the idea was, the practice was a fascinating feature of the steam-era railway and offered a degree of flexibility of service that simply isn’t possible on today’s railways.

A coach being slipped at Reading in 1947. Photograph by H N James, Colour Rail

Well, that’s it from me this year! I wish to thank the Going Loco team for their hard work bringing you this blog. My squad of fact checkers, Leigh, Ali and Harry. To drawings Kev for his occasional input. Website Rob for all his work on putting the blog up on the website. And finally, to Photo Frank. Who not only makes sure that this blog is beautifully illustrated but also checks that my English is well good. On behalf of them all, let me wish our readers a very happy Christmas and a peaceful and prosperous new year. See you in 2024!

A double-ended slip coach, built in 1938, at Swindon in 1962 in its final BR maroon livery. Double-ended means there was a slip compartment at both ends of the vehicle. The four circular-ended tanks in the centre below the frames were vacuum reservoirs which allowed the guard to release and apply the brakes several times to assist in stopping the coach at the correct place in the station after it was slipped. Photograph by Mike Peart

All the best,

Drew

FRIDAY 8 DECEMBER

Hidden Treasures – The Topflight Toplights

Here we are again – where has the week gone? Rather than discuss my inability to accurately process the passage of time, however, I figured we might take a look at another of the items in deep storage in the carriage shed, and using that as a springboard to talk about a hugely successful type of Great Western Railway passenger coach. Let’s get into our best Indiana Jones attire, sweep aside the spider’s webs and blow the dust off another hidden treasure!

The leading four vehicles of this train are non-corridor toplights, hauled by No 3702 Halifax in the 1920s

George Churchward was a genius. That’s probably beyond doubt to most people, but most of his fame is usually attributed to his locomotive designs but it must be remembered that he was in charge of the rest of the rolling stock on the Great Western. This is at a time when there were still a huge number of coaches that were of the four or six wheeled designs. This gave them short length bodies and a poorer ride when compared to more ‘modern’ long bogie coaches. To keep up with the rest of the railways in the UK, Churchward had to keep up with the modernisation of the coaching stock.

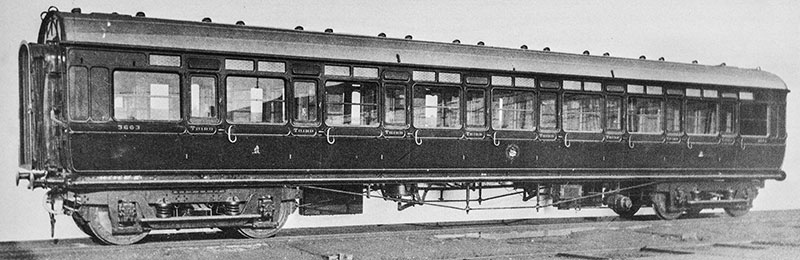

The corridor side of toplight No 3663, built in 1909. Photograph in A Pictorial Record of Great Western Coaches (1903-1948) by J H Russell

He had tried the Dreadnought and Concertina type coaches but for one reason or another, they hadn’t quite hit the mark. His best development was next and was the one that resulted in it being built in different forms to a total of 850 vehicles. The defining feature of these coaches are the small, hammered glass windows that were fitted above the main windows. They were sat just below the edge of the roof and were thus called Toplights. There were two main body types. A short 56’ - 57’ long version and a larger 70’ type. Unlike the previous wide bodied Dreadnought coaches, they were all built to 9’ wide. This meant that the recessed end doors weren’t required.

The compartment side of toplight No 3893, built in 1920. Photograph in A Pictorial Record of Great Western Coaches (1903-1948) by J H Russell

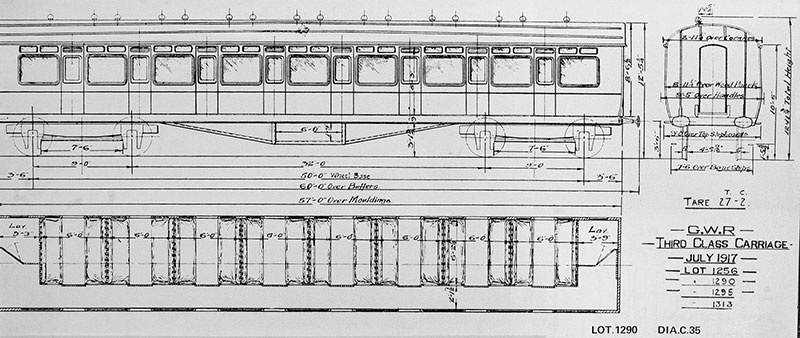

The first of these vehicles were completed in 1907. These were 56’ long and of the composite – or more than one class – variety. Diagrams E.83, E.84 and E.85 were built in batches up until 1909. They were just the start. Slip coaches*, full brakes**, suburban non-corridor, first class, brake thirds and even sleeper coaches were all turned out in this design. You will see them in some books described as being of ‘Bars 1’, Bars 2 or ‘Multibar’ type. This can be a bit confusing as there are no bars on the toplight windows! What this actually refers to is the arrangement of the supporting truss work under the chassis of the coach.

The wooden moulding was also phased out around the start of WW1, and although wooden panels continued for a while, eventually steel panels were substituted. What also gets confusing is that some of the later vehicles in the toplight series were built to the toplight design in all respects except without toplight windows .… The last of the toplight coaches were completed in the 1920s.

The diagram C35 for No 3963’s Lot. Drawing in A Pictorial Record of Great Western Coaches (1903-1948) by J H Russell

Despite introducing the history of the type today***, we have already encountered the toplight style designs in Going Loco. Twice. Our first encounter was when we looked at the Metropolitan & City Coaches Nos 3755 and 3756.**** We also saw them crop up when we chatted about WW1 veteran and Medical Officer’s coach No 1159. This coach, like many of its brethren, was converted to become part of a number of GWR hospital trains that served in Europe during the Great War.*****

Restored toplight 3rd No 3930, built 1915, on the Severn Valley Railway and being hauled by No 4079 Pendennis Castle during a Timeline Events photo charter on 18 April 2023

The majority of the toplights were used in the top trains until the 1930s, when the more modern coaching stock designed under Charles Collett fully took over. They went down through the secondary services until they were no longer considered useful for passenger services. They did soldier on however. There are about 20 of these vehicles preserved and many were used as camping coaches. Holiday homes on wheels, positioned at strategic points on the GWR network. Those coaches also then went on in many cases to serve in departmental service – to help keep the railway running.

The Camping Coaches at Dawlish Warren in 1959. No 3963 (then numbered W9885W and called Alice) is on the left, above the tree. Photograph in Amyas Crump Collection

There are fully restored examples in service on a couple of heritage railways but our example of a toplight coach ‘proper’ isn’t in such a great condition as those. No 3963 was built in 1919 to diagram C35 as part of Lot No 1256. It was an all third class coach originally but it was considered no longer useful in that form in the early to mid 1950s. This is one of those that was converted to a camping coach and that happened in 1955. Five of the passenger compartments were removed and turned into the main living areas of the holiday home. The three remaining compartments were reconfigured as bedrooms. The vehicle was positioned at least for some of its holiday service at Dawlish Warren.

No 3963 in store in the carriage shed at Didcot

No 3963 has had a somewhat nomadic existence since it was preserved in 1981. It entered preservation at the Gloucestershire and Warwickshire Railway but moved to the Llangollen Railway in 1988. Here it was used as staff accommodation. The final move for now was when the coach was purchased to become part of the collection at Didcot in 2012 .… and into store it went. It’s still there too. Awaiting its moment to be restored. There are no plans for that right now but it’s there, in the dry and safe. One day perhaps!

* Coaches that were released from the end of the train at speed. No, really! Sounds like a future blog to me…

** Coach bodied vehicles, but no passenger seats - for luggage and the like.

*** In the most over-simplified way possible! There isn’t enough room for all of it in Going Loco…

**** See the blog Going Underground, Going Underground... Part 1

***** See the blog Mysterious Medical Marvel

FRIDAY 1 DECEMBER

Gerroff My Manor!

There is a lot of talk about this class of locomotive at the moment amongst my model making friends as I have not long received my pre-ordered OO scale model of this type. Which set me thinking, I haven’t explicitly done the Manors as a class history. Let’s sort that out.

7809 Childrey Manor tackling the South Devon gradients in company with a Castle class 4-6-0. Photograph by John Ashman

The 78XX or Manor class has its origins in the other mid-sized Great Western Railway mixed-traffic tender engine, the 43XX class Moguls. These engines were designed by George Churchward as part of the locomotive standardisation programme he instigated. Despite being tacked on the end of the programme, their utility more than demonstrated the design’s effectiveness. The first of the Moguls were built in 1911 and by the 1930s they were getting a little long in the tooth, despite their usefulness and continued success.

The new boss at Swindon, Charles Collett, decided to make further use of the standardisation policy to update things in this area. Between 1936 and 1939, one hundred locomotives of the 43XX class were withdrawn. The components of eighty of these engines – namely the driving wheels and motion – were reused into a new class called the 68XX or Grange class. We need to chat about this one separately, but the basics were that it was essentially a small-wheeled version of the Hall class engines.

They were incredibly successful in their own right but they had one drawback. This was their red weight classification. This restricted them to just the main routes of the GWR network. Lighter locomotives that could operate on the company’s secondary and branch lines were also now looking a little tired and old so a new, light version of the Hall/Grange concept was needed. A ‘Diet’ Grange if you will .…

7815 Fritwell Manor at Gloucester Central with a stopping train to Hereford on 3 October 1959. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

The diet consisted primarily of reducing the size of the boiler. The Manor boiler requirement sat somewhere between the existing Standard 4 boiler of the Moguls and the Standard 1 of the Saints, Halls and Granges. Therefore, another design of boiler was needed. It needed to have a higher steaming rate and therefore a larger firebox capacity than the Standard 4 but keeping within the tight weight limits imposed by the route availability. The resulting Standard 14 boiler had a larger firebox that the Standard 4 and in theory this improved the steaming rate of the boiler. This was however to prove – for the first part of their career at least – the Achilles heel of the class. More of which later .…

The GWR’s policy of standardisation enabled locomotive components to be recycling among different classes – a part of the motion from No 7808 with numbers of 53XX class locomotives it had previously been fitted to

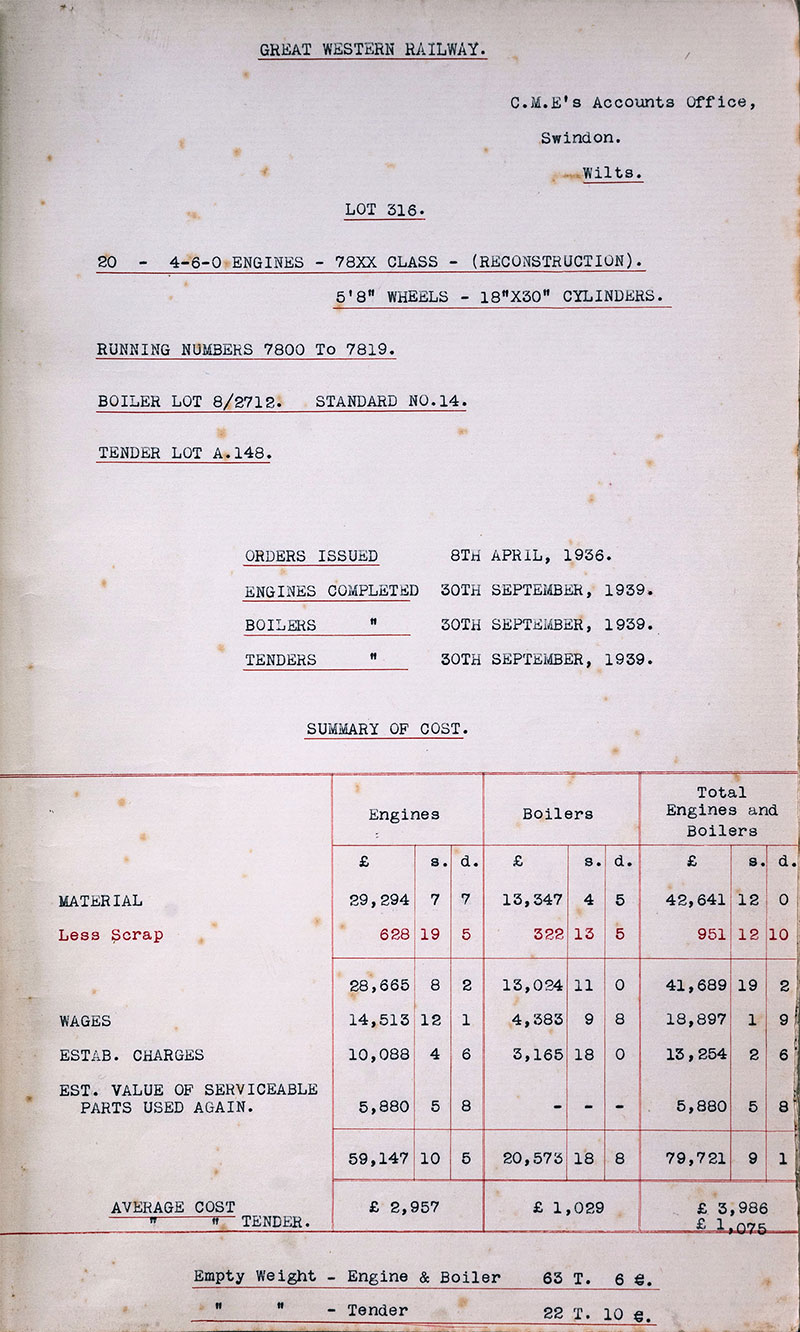

They had the Collett cab that had such unheard of luxuries (for the GWR crews at least!) as side windows and a roof that at least made a good attempt at keeping the weather off the crews. They were paired with the 3,500 gallon tenders which were the same types as fitted to the Moguls and were simply reconditioned rather than building them from new. This reuse of parts kept the costs down. The first four engines cost £3,986 and the tender heavy overhauls cost another £1,029. The first twenty were built between 1936 and 1939.

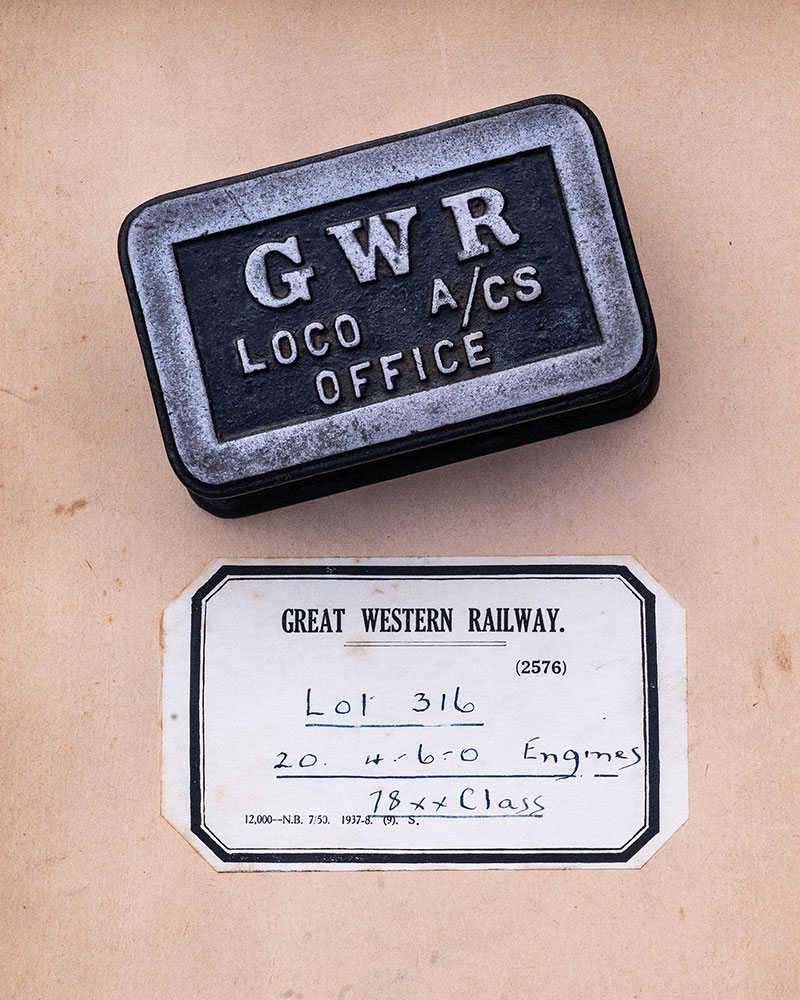

The Great Western Trust archive at Didcot Railway Centre does have a remarkable original GWR document – the official GWR Loco Lot book, for Lot 316, 20 4-6-0 engines 78XX class; issued by the Swindon Chief Mechanical Engineer's Accounts Office, relating to Manor class Locos Nos 7800-7819 ordered April 1936 and completed Sept 1939.

The cover of the Lot book for the first 20 Manor class, together with a Loco Accounts Office paperweight, both items in the Great Western Trust collection

It gives a listing of every component needed and associated labour costs!

A page from the book analysing the costs for Lot 316, Manor class Nos 7800 to 7819

The Manors weren’t an immediate success. It was found that their steaming rates were actually indifferent. They were not the success that it was hoped they would be when compared to their Mogul forbears. It is almost certain that they would have been recalled to Swindon en-masse if it was not for a certain set of events that morphed into World War II. Engines were needed – indifferent or not – and so they soldiered on.

Despite this, they did manage to fulfil their duties. They were initially based at a range of depots including Wolverhampton, Bristol, Gloucester and so on. However, No 7805 Broome Manor went to the former Cambrian Railways network for gauging trials. Once it was proofed that they would fit along the line, the class became synonymous with it. They worked in the West Country as well, in both cases their light weight allowing for high route availability. The second batch of twenty Manors was due to be built in 1939, but the war put paid to that. It wasn’t until the British Railways era that just ten more were finally constructed – beginning in 1950.

7815 Fritwell Manor at Oswestry on 12 April 1960. Photograph by Ben Brooksbank

The steaming issues were finally dealt with by a study undertaken at Swindon in 1952. Legendary Swindon engineer Sam Ell and his team made several modifications to steam pipes, the draughting and chimney arrangements and the fire bars. The results were dramatic. Previously, they had been able to steam at a rate of 10,000 pounds per hour. Post-modification, this was more than doubled to 20,400 pounds per hour. Needless to say, this utterly transformed the performance and indeed reputation of the class and they were now reaching their potential. This is the reason that they are so well remembered today.

7824 Iford Manor and 2-6-0 No 7310 double-heading the Festiniog Railway’s AGM special on 22 April 1961. Photograph by David Cooper in the Great Western Trust collection

The Cambrian Coast Express was a famous job for these rejuvenated machines. The train would start in Paddington behind a Castle or King class machine but they were just too big and heavy for the actual Cambrian Coast bit. The Manor would take over at Shrewsbury and pound its way through the Welsh countryside to Aberystwyth. This couldn’t last however. By the early 1960s the march of modernisation was eating into the classes of GWR 4-6-0s. The Manors were the last 4-6-0 class with all of its members in service, but that ended in April 1963 when No 7809 Childrey Manor was withdrawn and scrapped after she developed a large crack in one of her cylinders.

7814 Fringford Manor freshly outshopped at Swindon Works in 1962. Photograph by Mike Peart

The rest followed suit and by December 1965, the last two – No 7829 Ramsbury Manor and No 7808 Cookham Manor were withdrawn from Gloucester shed. No 7808 was preserved from there, and now has a home with the rest of the collection at Didcot. The remarkable thing about the Manors though is that another eight made their way to Dai Woodham’s scrapyard at Barry and all of these were preserved. When you think of it, for such a small class of thirty, the survival of nine of them is pretty remarkable. What is fortuitous about that is they are the perfect engine for the day-to-day operation of a heritage railway. Small and economical and yet with all the brass, copper and shiny nameplates that the average punter to a heritage railway likes to see. Most preserved lines are ex-branch lines too, so their light weight is a bonus there as well. They were almost made for the job. Which I suppose, in a way, they were .…

We will have a look at the history of our very own Manor some other time when I’ve had a chat with those that remember the early days.

|

|

|

|

Didcot Railway Centre Newsletter

Stay up to date with events and what's going on at Didcot Railway Centre.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We do not share your data with 3rd parties.